Chapter 67 Drowning and Submersion Injury

Epidemiology

Underlying Conditions

Several underlying medical conditions are associated with drowning at all ages. A number of studies have found an increased risk, up to 19-fold, in individuals with epilepsy. Drowning risk for children with seizures is greatest in bathtubs and swimming pools. Specific variants of long QT syndrome are associated with drowning; other causes of ventricular arrhythmias, including myocarditis, have been found in some children who die suddenly in the water (Chapters 429 and 430).

Pathophysiology

Anoxic-Ischemic Injury

With modern intensive care, the cardiorespiratory effects of resuscitated drowning victims are usually manageable and are less often the cause of death than irreversible hypoxic-ischemic central nervous system (CNS) injury (Chapter 63). CNS injury is the most common cause of mortality and long-term morbidity. Although the duration of anoxia before irreversible CNS injury begins is uncertain, it is probably on the order of 3-5 min. Victims with reported submersions of less than 5 min survive and appear normal at hospital discharge.

All other organs and tissues may exhibit signs of hypoxic-ischemic injury. In the lung, damage to the pulmonary vascular endothelium can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; Chapter 65). Aspiration may also compound pulmonary injury. Myocardial dysfunction (so-called stunning), arterial hypotension, decreased cardiac output, arrhythmias, and cardiac infarction may also occur. Acute tubular necrosis, cortical necrosis, and renal failure are common complications of major hypoxic-ischemic events (Chapter 529). Vascular endothelial injury may initiate disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hemolysis, and thrombocytopenia. Many factors contribute to gastrointestinal damage; bloody diarrhea with mucosal sloughing may be seen and often portends a fatal injury. Serum levels of hepatic transaminases and pancreatic enzymes are often acutely increased. Violation of normal mucosal protective barriers predisposes the victim to bacteremia and sepsis.

Pulmonary Injury

Pulmonary aspiration (Chapter 65) occurs in a majority of drowning victims, but the amount aspirated is usually small. Aspirated water does not obstruct airways and is readily moved into the pulmonary circulation with positive pressure ventilation. It can wash out surfactant and cause alveolar instability, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, and intrapulmonary shunting. In humans, aspiration of small amounts (1-3 mL/kg) can lead to marked hypoxemia and a 10-40% reduction in lung compliance. The composition of aspirated material can affect the patient’s clinical course: Gastric contents, pathogenic organisms, toxic chemicals, and other foreign matter can injure the lung or cause airway obstruction. Clinical management is not significantly different in saltwater and freshwater aspirations, because most victims do not aspirate enough fluid volume to make a clinical difference. A few children may have massive aspiration, increasing the likelihood of severe pulmonary dysfunction.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia (Chapter 69) is common after submersion. It is often categorized, according to core body temperature measurement, as mild (34-36°C), moderate (30-34°C), or severe (<30°C). Drowning should be differentiated from cold water immersion injury, in which the victim remains afloat, keeping the head above water without respiratory impairment. The definition of cold water varies from 60 to 70°F.

Management

Initial management of drowning victims requires coordinated and experienced prehospital care following the ABCs of emergency resuscitation (Chapter 62). These children often remain comatose and lack brainstem reflexes despite the restoration of oxygenation and circulation. Subsequent ED and PICU care often involve advanced life support strategies and management of multiorgan dysfunction.

Initial Evaluation and Resuscitation

The cervical spine should be protected in anyone with potential traumatic neck injury (Chapters 63 and 66). Cervical spine injury is a rare concomitant injury in drowning; only approximately 0.5% of submersion victims have cervical spine injuries. History of the event and victim age guide suspicion of cervical spine injury. Drowning victims with cervical spine injury are usually preteens or teenagers whose drowning event involved diving, a motorized vehicle crash, a fall from a height, a water sport accident, child abuse, or other clinical signs of serious traumatic injury. In such cases, the neck should be maintained in a neutral position and protected with a well-fitting cervical collar. Patients rescued from unknown circumstances may also warrant cervical spine precautions. In low-impact submersions, spinal injuries are exceedingly rare, and routine spinal immobilization is not warranted.

If the victim has ineffective respiration or apnea, ventilatory support must be initiated immediately (Chapter 62). Mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-nose breathing by trained bystanders often restores spontaneous ventilation. As soon as it is available, supplemental oxygen should be administered to all victims. Positive pressure bag-mask ventilation with 100% inspired oxygen should be instituted in patients with respiratory insufficiency. If apnea, cyanosis, hypoventilation, or labored respiration persists, trained personnel should perform endotracheal tube (ET) intubation as soon as possible. Intubation is also indicated to protect the airway in patients with depressed mental status or hemodynamic instability. Hypoxia must be corrected rapidly to optimize the chance of recovery.

Concurrent with securing of airway control, oxygenation, and ventilation, the child’s cardiovascular status must be evaluated and treated according to the usual resuscitation guidelines and protocols. Heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure, temperature, and end-organ perfusion require urgent assessment. CPR should be instituted immediately in pulseless, bradycardic, or severely hypotensive victims. Continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram (ECG) allows appropriate diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias. Slow capillary refill, cool extremities, and altered mental status are potential indicators of shock (Chapter 64). Recognition and treatment of hypothermia are the unique aspects of cardiac resuscitation in the drowning victim. Core temperature must be evaluated, especially in children, because moderate to severe hypothermia can depress myocardial function and cause arrhythmias.

Cardiorespiratory Management

For children who are not in cardiac arrest, the level of respiratory support should be appropriate to the patient’s condition and is a continuation of prehospital management. Frequent assessments are required to ensure that adequate oxygenation, ventilation, and airway control are maintained (Chapter 65). Hypercapnia should generally be avoided in potentially brain-injured children. Patients with actual or potential hypoventilation or markedly elevated work of breathing should receive mechanical ventilation to avoid hypercapnia and decrease the energy expenditures of labored respiration.

Measures to stabilize cardiovascular status should also continue. Conditions contributing to myocardial insufficiency include hypoxic-ischemic injury, ongoing hypoxia, hypothermia, acidosis, high airway pressures during mechanical ventilation, alterations of intravascular volume, and electrolyte disorders. Heart failure, shock, arrhythmias, or cardiac arrest may occur. Continuous ECG monitoring is mandatory for recognition and treatment of arrhythmias (Chapter 429).

The provision of adequate oxygenation and ventilation is a prerequisite to improving myocardial function. Fluid resuscitation and inotropic agents are often necessary to improve heart function and restore tissue perfusion (Chapter 62). Increasing preload with IV fluids may be beneficial through improvements in stroke volume and cardiac output. Overzealous fluid administration, especially in the presence of poor myocardial function, can worsen pulmonary edema.

Neurologic Management

Electroencephalographic monitoring has only limited value in the management of drowning victims and is generally not recommended, except to detect seizures or as an adjunct in the clinical evaluation of brain death (Chapter 63). Seizures should be treated if possible, although they tend to be very refractory. There is no evidence that treatment of seizures after drowning improves outcome. Fosphenytoin or phenytoin (loading dose of 10-20 mg of phenytoin equivalents [PE]/kg, followed by maintenance dosing with 5-8 mg of PE/kg/day in 2-3 divided doses; levels should be monitored) may be considered as an anticonvulsant; it may have some neuroprotective effects and may mitigate neurogenic pulmonary edema. Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and other anticonvulsants may also have some role in seizure therapy.

Other Management Issues

A few drowning victims may have traumatic injury (Chapter 66), especially if they were participating in water sports involving personal watercraft, boating, diving, or surfing. A high index of suspicion for such injury is required. Spinal precautions should be maintained in victims with altered mental status and suspected traumatic injury. Significant anemia suggests trauma and internal hemorrhage.

Manifestations of acute renal failure may be seen after hypoxic-ischemic injury (Chapter 529). Diuretics, fluid restriction, and dialysis are occasionally needed to treat fluid overload or electrolyte disturbances; renal function usually normalizes in survivors. Rhabdomyolysis after drowning has been reported.

Hypothermia Management

Damp clothing should be removed from all drowning victims. Attention to core body temperature starts in the field and continues during transport and in the hospital. The goal is to prevent or treat moderate or severe hypothermia. Rewarming measures are generally categorized as passive, active external, or active internal (Chapter 69). Passive rewarming measures can be applied in the prehospital or hospital setting; they include the provision of dry blankets, a warm environment, and protection from further heat loss. Rewarming measures should be instituted as soon as possible for hypothermic drowning victims who have not had a cardiac arrest.

Full CPR with chest compressions is indicated for hypothermic victims if no pulse can be found or if narrow complex QRS activity is absent on ECG (Chapters 62 and 69). When core body temperature is <30°C, resuscitative efforts should proceed according to the current American Heart Association guidelines for CPR, but IV medications may be given at a lower frequency in moderate hypothermia because of decreased drug clearance. When VF is present in severely hypothermic victims (core temperature <30°C), up to 3 defibrillation attempts should initially be delivered, but further defibrillation attempts should be held until the core temperature is ≥30°C, at which time successful defibrillation may be more likely.

Prevention

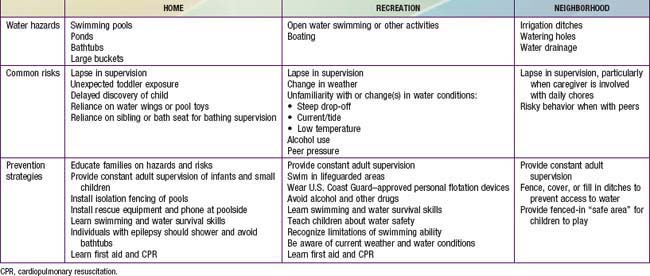

Parents must build layers of water protection around their children. Table 67-1 provides an approach to the hazards and preventive strategies relevant to the most common sources of water involved in childhood drowning. A common preventive strategy for exposure to all water types and all ages is ensuring appropriate supervision. Pediatricians should define for parents what constitutes appropriate supervision at the various developmental levels of childhood. Many parents either underestimate the importance of adequate supervision or are simply unaware of the risks associated with water. Even parents who say that constant supervision is necessary will often admit to brief lapses while their child is alone near water. Parents also overestimate the abilities of older siblings; many bathtub drownings occur when an infant or toddler is left with a child younger than 5 yr.

Two of the preventive strategies listed in Table 67-1 deserve special mention. The most vigorously evaluated and effective drowning intervention applies to swimming pools. Isolation fencing that completely surrounds a pool, with a secure, self-locking gate, reduces the risk of drowning. Guidelines for appropriate fencing, provided by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, are very specific; they were developed through testing of active toddlers in a gymnastics program on their ability to climb barriers of different materials and heights. In families who have a pool on their property, caregivers often erroneously believe that if a child falls into the water there will be a loud noise or splash to alert them. Sadly, these events are usually silent, increasing the time until the child is discovered. This finding highlights the importance of the guideline that the fence actually separate the pool from the house, not just surround the entire property.

Brenner RA, Taneja GS, Haynie DL, et al. Association between swimming lessons and drowning in childhood: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:203-210.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Nonfatal and fatal drownings in recreational water settings—United States, 2001–2002. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:447-452. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5321a1.htm.

Cohen RH, Matter KC, Sinclair SA, et al. Unintentional pediatric submersion-injury-related hospitalizations in the United States, 2003. Inj Prev. 2008;14:131-135.

Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy Statement—prevention of drowning. Pediatrics. 2010;126:178-185.

Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Swimming programs for infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2000;105:868-870.

Diplock S, Jamrozik K. Legislative and regulatory measures for preventing alcohol-related drownings and near-drownings. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:314-317.

Garssen MJ, Hoogenboezem J, Bierens JJ. Reduction of the drowning risk for young children, but increased risk for children of recently immigrated non-westerners. [See comment.]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152:1216-1220.

Jonkman SN, Kelman I. An analysis of the causes and circumstances of flood disaster deaths. Disasters. 2005;29:75-97.

Kenny D, Martin R. Drowning and sudden cardiac death. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:5-8.

Lee LK, Thompson KM. Parental survey of beliefs and practices about bathing and water safety and their children: guidance for drowning prevention. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39:58-62.

Mao SJ, McKenzie LB, Xiang H, et al. Injuries associated with bathtubs and showers among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:541-547.

McCool J, Ameratunga S, Moran K, et al. Taking a risk perception approach to improving beach swimming safety. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16:360-366.

Moran K, Stanley T. Parental perceptions of toddler water safety, swimming ability and swimming lessons. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2006;13:139-143.

Quan L, Bennett E, Branche CM. Interventions to prevent drowning. In: Doll L, Bonzo S, Sleet D, et al, editors. Handbook of injury and violence prevention. New York: Springer; 2007:81-96.

Rahman A, Shafinaz S, Linnan M, et al. Community perception of childhood drowning and its prevention measures in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16:176-180.

Rivara FP. Prevention of drowning. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:277-278.

Runyan CW, Casteel C, Perkis D, et al. Unintentional injuries in the home in the United States part I: mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:73-79.

Saluja G, Brenner RA, Trumble AC, et al. Swimming pool drownings among US residents aged 5–24 years: understanding racial/ethnic disparities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:728-733.

Taneja G, van Beeck E, Brenner R. Drowning. In: Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozanne-Smith J, et al, editors. World report on child injury prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008:58-73.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Safety barrier guidelines for home pools. Publication 362. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, Washington, DC, 2007.

Yang L, Nong QQ, Li CL, et al. Risk factors for childhood drowning in rural regions of a developing country: a case-control study. Inj Prev. 2007;13:178-182.

Yuma P, Carroll J, Morgan M. A guide to personal flotation devices and basic open water safety for pediatric health care practitioners. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:214-218.