6 Drowning

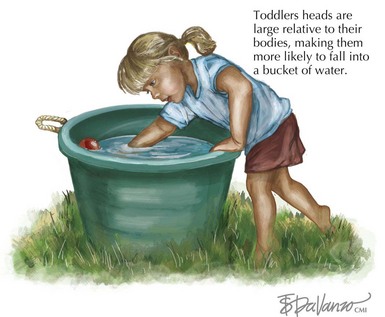

Pediatric drowning is the second leading cause of accidental childhood death in the United States, surpassed only by motor vehicle collisions. It is most common in young toddlers and adolescents, and boys are more likely to drown in all age groups. Toddlers are most likely to drown in small, household water sources such as bathtubs and buckets. Inadequate adult supervision is often responsible, although children have usually been out of sight for less than 5 minutes. Toddlers have large heads relative to their bodies, making them more likely to fall forward into buckets or tubs and less able to right themselves (Figure 6-1). Adolescents are more likely to drown during recreational activities such as boating and in natural bodies of water. Alcohol use contributes to up to 50% of teenage drownings. Pediatric drownings carry high morbidity and mortality; 30% to 50% of drowning victims die, and 10% survive with severe neurologic impairment.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

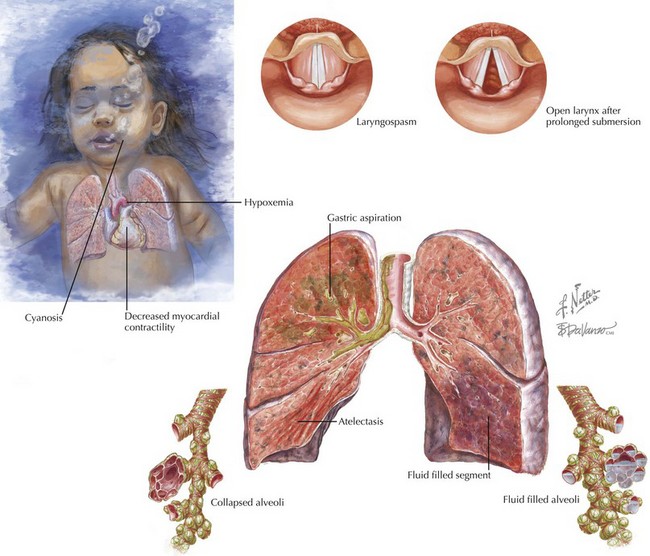

The effects of aspiration and continued submersion are many (Figure 6-2). Within the alveoli, water prevents diffusion of oxygen across the capillary/alveolar membrane. The capillary endothelium becomes increasingly permeable, resulting in pulmonary edema. Aspiration of gastric contents contributes to lung injury. As pulmonary edema and intrapulmonary shunt progress, hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis ensue. These metabolic disturbances decrease myocardial contractility, increase systemic vascular resistance, and contribute to arrhythmias. If submersion continues long enough, drowning will progress to cardiac arrest. Clinically, there is little difference between fresh and salt-water drownings; however, there are some putative pathophysiologic differences. Whereas fresh water is particularly destructive to surfactant, salt water causes osmotic forces to draw additional fluid into the alveoli. Electrolyte disturbances are rare; however, ingestion of large amounts of fresh water can cause hyponatremia, and salt water ingestion can cause hypernatremia. Ingestion of large quantities of fresh water in the setting of hypoxemia may lead to hemolysis, although this is also a rare event.

Clinical Presentation

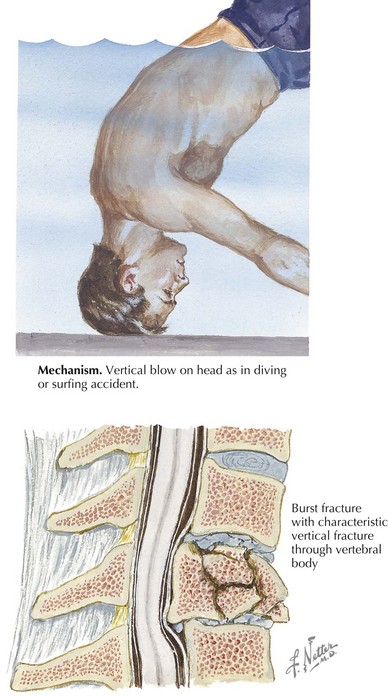

It is important to consider potential coexistent injuries and risk factors for drowning. Drowning may be associated with other trauma, including head injury, blunt abdominal trauma, and spinal injury (Figure 6-3). Seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, hypoglycemia, and intoxication can all contribute to a drowning event.

Evaluation and Management

Unresponsive patients should be evaluated according to Basic Life Support guidelines and receive CPR as indicated at the scene (see Chapter 1). The Heimlich maneuver and attempts to drain water from the lungs should be avoided. Further cooling of the patient should be prevented by removing wet clothing and insulating the patient with dry blankets. Prehospital care and ED providers should evaluate the patient’s airway and ventilatory efforts, provide oxygen, and consider intubation. Unresponsive and hypoxic patients most likely require intubation because vomiting is common, and lung injury will probably continue to worsen. If cervical spine (c-spine) injury is a possibility, resuscitation should occur with c-spine immobilization throughout. Gastric decompression is an important step in early resuscitation. Use of a nasogastric or orogastric tube to remove stomach contents decreases vomiting and aids in ventilation by allowing easier distension of the lungs.

After acute resuscitation and management of airway, breathing, and circulation, evaluation for concomitant injury and the underlying cause of drowning should occur. Circumstances surrounding the event help guide this workup, and evaluation of a patient with a suspected traumatic mechanism should follow the approach to the trauma patient (see Chapter 8). A history of high-impact trauma such as diving, striking an object, or being in a motorized boat increases the likelihood of requiring computed tomography scans to evaluate for c-spine, intraabdominal, or head injuries. The serum glucose level should be checked both to detect causative hypoglycemia and to preserve normoglycemia. Hypoxic-ischemic injury to the liver and kidneys may present as coagulation abnormalities and acute tubular necrosis.

Bierens JJ, editor. Handbook on Drowning. The Netherlands: Springer, 2004. Available at http://www.drowning.nl

Bierens JJ, Knape JT, Gelissen HP. Drowning. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8:578-586.

Layon AJ, Modell JH. Drowning: update 2009. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1390-1401.

Meyer RJ, Theodorou AA, Berg RA. Childhood drowning. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:163-169.

Moon RE, Long RJ. Drowning and near-drowning. Emerg Med. 2002;14:377-386.

Thompson DO, Rivara F. Pool fencing for preventing drowning in children. The Cochrane Collection Web Site Available at http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab001047.html, 2011.

Watson RS, Cummings P, Quan L, et al. Cervical spine injuries among submersion victims. J Trauma. 2001;51:658-662.

Zuckerbraun NS, Saladino RA. Pediatric drowning: current management strategies for immediate care. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;6:49-56.