Chapter 29 Drowning

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In Australia 39 children died from drowning in 2000/1, and the 5-year average was 35, a figure again reached in 2006/7. In 2006/7 277 people overall drowned, an increase of 13% on the 5-year average. Males of all ages, except those aged 0–4 years, were almost three times as likely as females to drown and, while the number of drowning deaths in lagoons and lakes dropped by 53% compared to the 5-year average, drownings at the beach increased by 39%. Deaths in over 55s remained stable at the average. The most common location of drowning among children was in domestic swimming pools, with the second commonest location being in the bath. Indigenous Australians are four times more likely to drown than other Australians, and alcohol or drug use was implicated in 14% of accidental drownings in Australia, of whom 79% were males.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

What appears clear is that initial voluntary breath holding precedes a variable degree of aspiration of water, followed eventually by apnoea, with the common pathway in all drowning being profound hypoxia associated with acidosis and hypercapnoeia. This hypoxia not only leads to unconsciousness, loss of airway reflexes and aspiration, but also leads to the cardiovascular effects of drowning. These include extreme bradycardia, ventricular fibrillation and asystole, which are often exacerbated by hypothermia in cold waters. Hypothermia is common in child victims of drowning due to their large surface area:body mass ratio and, although hypothermia has been associated with a poor prognosis after drowning as it is related to the duration of submersion, it has also been associated with a better prognosis, particularly in children, presumably due to a protective effect on cerebral organ function with the rapid onset of low temperatures. There have been several cases reported of survival of both children and adults following submersion in cold water for up to 66 minutes.

OUTCOME

Individuals with any of these features have been reported to survive without disability, although the chances of successful resuscitation to a favourable neurological outcome are usually slim. Importantly, age has no independent association with outcome.

Drowning victims may be classified into one of four groups based on presenting physical examination:

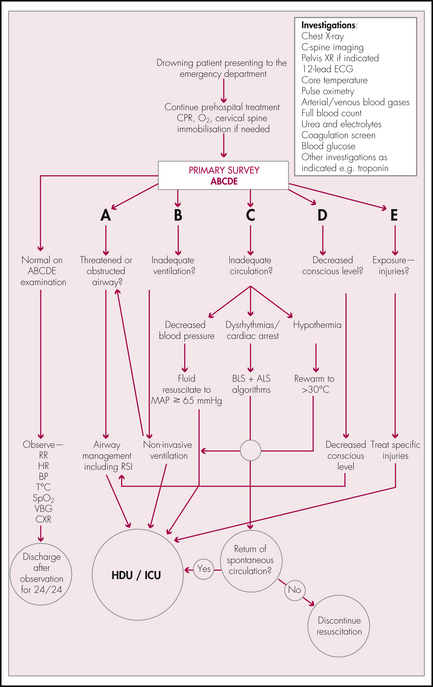

INVESTIGATIONS

Later investigations may include computerised tomography (CT) of the head and neck.

MANAGEMENT

Airway

Manual in-line immobilisation should be employed during airway management if there is a history or a suspicion of trauma, particularly in diving accidents. Adjuncts such as rigid cervical collars, sandbags and tape assist in immobilising an at-risk cervical spine, although their limitations should be known, particularly in children where an immobilised and

restrained head and neck may lead to a mobile body. Care must be taken not to manage a potential cervical spine injury to the detriment of efficient airway management.

Breathing

Indications for RSI and intubation may be:

Note: Venous blood gases are appropriate for trend monitoring but, although PvCO2 is reproducibly 5 mmHg higher than PaCO2, a trend of increasing PvCO2 is most important.

Circulation

Rewarming is essential (see the ‘Hypothermia’ section in Chapter 32): wet clothing should be removed, the skin should be dried and the patient should be wrapped in warm blankets with aluminium foil outside this. Intravenous fluids should be warmed to 40°C; ventilator circuits should contain a humidifier/warmer to ensure ventilatory gases are also close to body temperature. Children lose heat quickly due to the large surface area:body mass ratio and therefore careful management of temperature is mandatory.

Dysfunction

Cerebral function is best preserved by prompt and effective management of airway, breathing and circulation. Neurological observations and sequential recording of GCS monitors trends.

Final recommendations of the World Congress on Drowning. Amsterdam 26–28 June 2002. Online. Available: http://www.cslsa.org/events/ArchiveAttachments/Spr03Minutes/AttachmentG2.pdf.

Ibsen L.M., Koch T. Submersion and asphyxial injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S402-S408.

Idris A.H., et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from drowning; the “Utstein” style. Circulation. 2003;108:2565-2574.

Salomez F., Vincent J.-L. Drowning: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment and prevention. Resuscitation. 2004;63:261-268.

Shepherd SM, Martin J, Norris R et al. Drowning. Online. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/TOPIC744.HTM.

The Royal Life Saving Society Australia. The National Drowning Report. 2007. Online. Available: http://www.royallifesaving.com.au/www/html/2269-2008-national-drowning-report.asp.

Watson R.S., Cummings P., Quan L., et al. Cervical spine injuries among submersion victims. J Trauma. 2001;51:568-662.