6 Dosage and dosage forms in herbal medicine

Chapter contents

The subject of appropriate dose is probably the most controversial aspect of contemporary Western herbal medicine. Among Western herbal practitioners, many different dosage approaches are found from country to country and within countries. Underlying these different approaches are different philosophies about the therapeutic action of medicinal plants.

• dosage ranges used in other important herbal traditions, e.g. China and India

• dosages used by important historical movements in Western herbal medicine, e.g. the Eclectics

• dosages currently recommended in pharmacopoeias

• dosages established from pharmacological and clinical research.

Review of dosage approaches

Traditional Chinese medicine

The daily dose for individual non-toxic herbs in traditional Chinese medicine is usually in the range of 3 to 10 g, given as a decoction or in pill or powder form.1 Often higher doses are prescribed by decoction than for pills, as might be expected since not all active components readily dissolve in hot water.2 (Pills generally consist of the powdered herb incorporated into a suitable base.) Herbs are invariably prescribed in formulations. Doses for such formulations are about 3 to 9 g taken three times daily but can be higher in the case of decoctions.

For each individual herb, a wide dosage range is usually given in texts. (This applies for all herbal systems.) One reason for this is that if a herb is used by itself or with just a few other herbs, a larger dose is used than when it is combined with many other herbs.2 Dose also varies according to the weight and age of patients and the severity or acuteness of their condition.

Some herbs, or closely related species, are used in both Chinese and Western herbal medicine. Table 6.11,3,4 compares dosages for a few of these herbs.

Table 6.1 Comparison of dosages used in Chinese and Western herbal medicine

| Herb | Chinese dosage1 g/day | Western dosage3,4 g/day |

|---|---|---|

| Ephedra sinica | 3–9 | 3–9 (extract) |

| 3–12 (decoction) | ||

| Zingiber officinale | 3–9 | 0.75–3 (decoction) |

| 0.38–0.75 (tincture) | ||

| Taraxacum mongolicum | 9–30 | 6–24 (decoction) |

| 3–6 (tincture) | ||

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | 3–12 | 3–12 (decoction) |

| 6–12 (extract) | ||

| Rheum palmatum | 3–6 | 2.3–4.5 (decoction) |

| 1.8–6 (extract) |

Note: For dosages of tinctures and extracts given three times daily, the corresponding amount of dried herb per day has been calculated.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda often involves complex formulations which are prepared over several days and can contain many herbal and mineral components. Consequently, there is more dosage diversity than for Chinese medicine. Dosage ranges for individual non-toxic herbs are generally in the region of 1 to 6 g/day as powders or tinctures, with higher doses often recommended for decoctions.5

Eclectic medicine

Eclectic medicine was a largely empirical school of medicine which developed in America during the 19th century.6 The movement was most prominent for a brief period from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, when there were several teaching universities and many eminent scholars in the USA. Although the Eclectics used simple chemical medicines such as phosphoric acid, they mainly prescribed herbal medicines. Their knowledge of materia medica was their greatest contribution to Western herbal medicine; for example, herbs such as Echinacea and golden seal were made popular by them after observation of their use by the Native Americans.

The Eclectics tended to use higher doses than those recommended in current texts and pharmacopoeias, although the ranges tend to overlap. Table 6.2 compares dosages currently used3,4 with those found in Eclectic texts7,8 for alcoholic extracts of herbs.

Table 6.2 Comparison of dosages used by the Eclectics and modern dosages

| Herb | Eclectic dosage7,8 g/day | Current dosage3,4 g/day |

|---|---|---|

| Euphorbia hirta | 1.8–10.8 | 0.36–0.9 |

| Echinacea angustifolia | 0.9–5.4 | 0.75–3.0 |

| Hydrastis canadensis | 0.9–10.8 | 0.9–3.0 |

| Passiflora incarnata | 1.8–10.8 | 1.5–3.0 |

| Valeriana officinalis | 2.1–6.0 | 0.9–3.0 |

| Rumex crispus | 1.8–10.8 | 6.0–12.0 |

| Viburnum opulus | 3.6–10.8 | 6.0–12.0 |

| Serenoa repens | 2.7–10.8 | 1.8–4.5 |

Note: The corresponding amount of dried herb per day has been calculated from recommended dosages for fluid extracts.

The British Herbal Pharmacopoeia

The British Herbal Pharmacopoeia 1983 (BHP) carries extensive dosage information for individual herbs and is generally regarded as an important traditional reference on this subject for Western herbal practitioners. Dosages given in the BHP were derived from earlier texts such as the British Pharmacopoeia (BP) and the British Pharmaceutical Codex (BPC) but also resulted from a survey of herbal practitioners. More recently, the British Herbal Compendium (BHC) has been published in two volumes, with dosage information for the practitioner.9,10

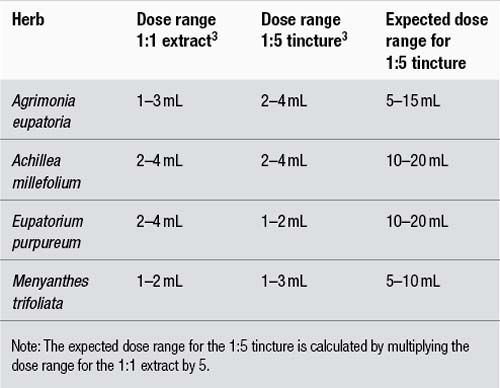

The doses given by the BHP 1983 contain some inconsistencies. The main problem is that doses for tinctures often do not correlate to corresponding doses for liquid extracts. For a 1:1 extract and a 1:5 tincture of a particular herb to correlate in terms of dose, the dose range for the tincture should be five times that of the extract, since it is theoretically five times weaker. This problem contrasts with other pharmacopoeias such as the BPC 1934 where the correlation is generally, but not exactly, observed. Some examples that highlight this problem are provided in Table 6.3.

The poor correlation demonstrated in Table 6.3, where in the case of Eupatorium purpureum the tincture dose is actually less than the extract dose, probably arises for two reasons:

1. As stated above, the BHP 1983 doses were in part derived from a survey of herbal practitioners. It is probable that there were different dosage philosophies between practitioners using extracts compared to those using tinctures. Hence, a correlation should not be expected.

2. Tinctures are manufactured using different techniques to 1:1 fluid extracts. This is particularly important. Fluid extracts can be prepared by reconstituting more concentrated extracts, rather than the traditional method of reserved percolation. In either case, the heat or vacuum used in concentration can rob the preparation of important active chemicals. Tinctures better preserve the activity of the whole plant because they are made without heat or a concentration procedure. Fluid extracts were also often manufactured using lower alcohol strengths than tinctures, and important active components may therefore not be extracted from the starting plant material. The result of these factors is that a 1:1 fluid extract can have an activity which is much less than five times that of a 1:5 tincture. This will be dealt with in more detail in the part of this chapter that discusses liquid preparations.

Commission E and ESCOP monographs

A positive monograph for a herb also included dosage information. Many of the monograph doses are for infusions or decoctions since this reflects the common use of teas in the German marketplace.11 Such daily doses are usually in the range of 2 to 10 g. Occasionally a monograph will specify a dose for a herb in terms of major active constituents; for example, for Ephedra the daily dose is 45 to 90 mg of alkaloids (about 4 to 8 g of herb) which is similar to the range in Table 6.1. Occasionally, where tincture and extract doses are given by the Commission E, there is not always a good correlation. For example, the single dose for valerian tincture is 1 to 3 mL and yet the single dose for a fluid extract is 2 to 3 mL. The reasons for this may be the same as those discussed above for the BHP 1983.

The Scientific Committee of ESCOP (European Scientific Cooperative of Phytotherapy) has published a series of herbal monographs.12,13 These were compiled by an international team of expert authors and represent a major contribution to the harmonisation of standards for herbal medicines across the European Union. These monographs contain useful dosage information reflecting the European situation and have been taken into account for the dosage recommendations in this text.

Clinical trials

The clinical trial is arguably the best way to determine the effective dose of either a single herb or a herbal formulation. This will not always be applicable to traditional medicine, however, since prescriptions are usually prepared on an individual basis. Also, a clinical trial does not necessarily determine the optimum dose. However, it does confer a relative certainty to the clinical results. That is, at a given dose of a given preparation a certain percentage of patients are likely to respond; for example, Ginkgo biloba standardised extract at 120 mg/day (which corresponds to about 6 g/day of dry leaves), given for 2 months, will improve intermittent claudication in 60% of patients.14

Sometimes the clinical trial has used a standardised extract of the herb which can then be correlated to the whole herb; for example, silymarin in liver disorders at 240 mg/day corresponds to 8 to 16 g/day of Silybum marianum seeds.15

The low dosage approach

In Europe, homeopaths often use combinations of herbal mother tinctures in drop dosage, for example, ‘drainage’. This approach is sometimes incorrectly labelled as ‘phytotherapy’.

In the USA a more direct influence comes, ironically, from a development of Eclectic medicine. In 1869, the Eclectic physician John Scudder proposed the concept of ‘specific medication’.7 With this concept, medicines were matched specifically to the symptom picture of the patient and then given in the minimum dose required. Although this system may seem similar to homeopathy, there were important differences.16 Material doses were always used, albeit lower than those prescribed by other Eclectics, and the prescription was not based on the law of similars. However, like classical homeopathy, there was a tendency to use only one medicine at a time.

Scudder initially proposed that ‘specific medicines’ should be tinctures prepared from the fresh plant.16 A fresh plant tincture is sometimes still called a ‘specific tincture’. Hence, the approach of using drop doses of tinctures, especially fresh plant tinctures, also comes from Scudder.

Although Scudder’s system of specific medication was seen as an important development in Eclectic medicine, it was considerably modified by Lloyd.17 Lloyd felt that drop doses of tinctures were too low and described the preparations proposed by Scudder as ‘superficial’. Lloyd proceeded to develop elaborate herbal preparations which were concentrated, semi-purified liquids. He also called these ‘specific medicines’ and they were widely adopted by Eclectic practitioners. However, in the early 20th century English herbalists aligned themselves with the American physiomedicalists in using simpler formulations, because Lloyd’s specific medicines proved too costly to import.

Lloyd sometimes used solvents other than ethanol and water in the preparation of his specific medicines.17 His methods were kept secret and even today are not widely known. Lloyd writes: ‘The aim has been to exclude colouring matters … and inert extractive substances also from these preparations …’. In this sense, he was tending towards the concept of orthodox drugs. However, his preparations were still chemically complex and ‘very characteristic’ of the original herb.17 According to Felter, the specific medicines developed by Lloyd were at least eight times stronger than 1:5 tinctures.7 It is these highly concentrated preparations which were generally used by Eclectic physicians in drop doses, and even then doses could be quite high – up to 60 drops (3 mL) three times daily.7

The current system in the UK

In the UK in the past herbalists used fluid extracts, usually prepared using heat or from concentrates. However, among newer practitioners in the 1980s there was disenchantment with these preparations because of their inconsistent quality. These practitioners instead adopted the use of 1:5 tinctures. Usually, formulations of tinctures are prescribed at doses of 2.5 to 5 mL three times daily. However, BHP 1983 doses for tinctures can only be achieved by this approach if the formulation contains one to three herbs (see Table 6.3 for examples). Unfortunately, this restriction is usually not followed and it can be concluded that the move to tinctures has resulted in the use of lower doses.

Oral dosage forms in herbal medicine

Liquids

Superior bioavailability is also an under-researched advantage of herbal liquids. When a solid dosage preparation is ingested, it must first disintegrate. The plant’s phytochemicals need to dissolve in digestive juices (and the water simultaneously imbibed with the tablet or capsule) in order to be absorbed by the body. Research has demonstrated that there is a relationship between the rate and degree of dissolution of the phytochemicals in a solid dosage preparation and their ultimate absorption into the bloodstream. The advantage of herbal liquids is that the all-important phytochemical constituents are already in solution.

Tablets

Sometimes only tablets can confer clinically effective doses. Some herbal products have been shown in clinical trials to be only effective at high doses. If these herbs were given in liquid form, the doses of liquid needed would be impractically high. A good example of this is the willow bark tablet that contains around 8 g of willow bark. This means that each tablet is equivalent to 16 mL of a 1:2 liquid extract. The only practical way to give such clinically effective doses of willow bark, based on clinical trials, is to use a herbal tablet.

The preparation of liquids

The strength or ratio

The strength of a liquid preparation is usually expressed as a ratio. For example, 1:5 means that 5 mL of the final preparation is equivalent to 1 g of the dried herb from which the preparation was made. Liquid preparations weaker than 1:2 are usually called ‘tinctures’ whereas 1:1 and 1:2 preparations are typically called ‘extracts’. Tinctures are usually made by a soaking process known as maceration, whereas extracts are best made using percolation. However, tinctures can also be adequately manufactured by a percolation process. These days, 1:1 liquid extracts can be made by reconstituting soft or powdered concentrates (not recommended).

It has been argued that 1:2 extracts are relatively new, are not mentioned in the BHP 1983 or other pharmacopoeias and therefore should not be used. In fact, 1:2 extracts are mentioned in 19th century texts16,18 and were described in the German Pharmacopoeia (DAB). The seventh edition of the DAB actually defines a liquid extract as a 1:2 extract.19

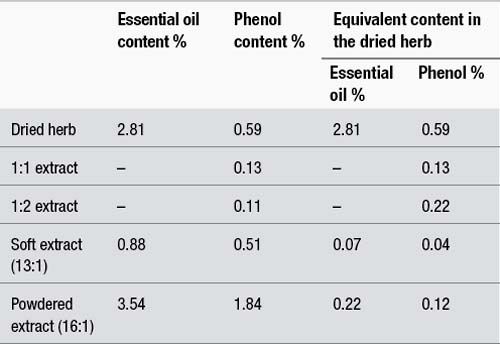

The dominant historical use of 1:1 extracts may not have been the wisest choice because of the extra processing required. In 1953, a Dutch PhD student studied the impact of pharmaceutical processing on some active components of thyme (Thymus vulgaris).20 The components tested were the phenols (thymol and carvacrol), which are responsible for the antiseptic activity of thyme. Thymol and carvacrol are found in the essential (volatile) oil of thyme and could conceivably be lost under conditions of vacuum or heat. The following preparations were made:

1. A 1:1 liquid extract in 50% ethanol by the method of reserved percolation, which is described in most pharmacopoeias

2. A 1:2 liquid extract in 50% ethanol by cold percolation

3. A soft extract (13:1) by evaporating some of the liquid described in (2) under vacuum

4. A powdered extract (16:1) by drying some of the liquid described in (2) in a spray dryer.

The phenol content in all four preparations and in the original herb was measured and the results are summarised in Table 6.4. The table also provides the essential oil content of some of the preparations.

As can be seen from Table 6.4, the 1:2 extract contains only marginally less phenol content than the 1:1. This is presumably because the phenols were largely lost during the heating of the second percolate which occurs in reserved percolation. Hence, on the basis of the active components tested, the 1:2 is almost as strong as the 1:1. It should be noted from Table 6.4 that neither the 1:1 nor the 1:2 quantitatively extracted all the phenols from the dried herb, presumably because these components were not completely soluble at the ethanol percentage chosen. The 1:2 contained 37% of the original phenol content in the dried herb, compared to 22% for the 1:1.

The results for the soft and powdered extracts are disturbing. For the soft extract, 82% of the phenols were lost in processing, and for the powdered extract the loss was 48%. Compared to spray drying, conditions of vacuum therefore seem more likely to cause the loss of essential oil components, although the losses in both cases are considerable. A Swiss study found that concentration of a chamomile extract under vacuum caused the loss of about half of the essential oil.21

The content of essential oil and phenols in the corresponding amount of dried herb are also provided for the various preparations in the right-hand columns of Table 6.4. As can be seen from the table, the soft and powdered extracts only contain a fraction of the essential oil and phenol content of the dried herb. Hence, for this example, the use of these concentrates in the manufacture of liquids, tablets or capsules would clearly represent a substantial sacrifice of quality for the sake of an increase in quantity. If the soft extract was reconstituted to a 1:1 which is a common practice, it would contain about 30% of the phenol content of the 1:2 (0.04% versus 0.11%).

Ethanol-water as the solvent

Ethanol (or alcohol) has been used for hundreds of years to prepare liquid herbal preparations and indeed ethanol-water mixtures do appear to be quite efficient for the extraction of a wide variety of compounds found in medicinal plants. Chemical analyses of organic substances absorbed into pottery jars have recently confirmed the use of medicinal wines in ancient Egypt (about 3150 bc and millennia thereafter) and ancient China (seventh millennium bc). The ancient Egyptian wine contained herbs and tree resins dispensed in wine made from grapes. The jar from ancient China contained a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey and fruit (hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) fruit and/or grape). The medicinal use of wines has been described in ancient documents, and the early Chinese history of fermented beverages is suggested from the shapes and styles of Neolithic pottery vessels.22,23 Ancient Egyptian papyri describe water, milk, oil (presumably olive oil), honey, beer and wine as carriers for medicinal herbs. Jewish medicine, described in the second-century Talmud, refers to a ‘potion of herbs’ mixed with beer or wine.24

Although the principle of distillation was known to the ancient Greeks, the Arabs adapted the process to produce alcohol, which they then used for medicinal purposes. (The word alcohol, which first appeared in most modern languages in the 16th century, was derived from Arabic (al-koh’l).)25

The first official British Pharmacopoeia, the London Pharmacopoeia, was issued in 1618. It contained a section outlining ethanolic fluid extracts and drew heavily on the classics.26

Nicholas Culpeper, the 17th century English herbalist and one of the best-known advocates of Western herbal medicine, described the distillation of one or more herbs in wine, and the maceration of spices in alcohol. Single herbs, such as dried wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis), were steeped in wine and set in the sun for 30–40 days to make a physical wine.27

A number of studies have highlighted the importance of the correct choice of the ethanol percentage in terms of maximising the quality of liquid preparations. The Swiss study mentioned above found that 55% ethanol was the optimum percentage for the extraction of the essential oil from chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla).21 Higher percentages of ethanol did not extract any additional oil and there was a decrease in the solids content of the extract, which indicates that other components were being less efficiently extracted. More recently, Meier found that 40–60% ethanol was the optimum range for achieving the highest extraction efficiency for the active components of a variety of herbs.28 For example, at 25% ethanol, none of the saponins in ivy leaves (Hedera helix) was extracted, but at 60% ethanol they were maximally extracted.

Higher ethanol percentages do not always confer higher activity. French researchers found that Viburnum prunifolium bark extracted at 30% ethanol was five times more spasmolytic than a 60% extract.29

The basic guidelines for the choice of the ethanol percentage to optimise the activity of the final liquid are as shown in Table 6.5.

Table 6.5 Choice of ethanol percentage to optimise the activity of final liquid

| Ethanol (%) | Final liquid |

|---|---|

| 25% | Water-soluble constituents such as mucilage, tannins and some glycosides (including some flavonoids and a few saponins) |

| 45–60% | Essential oils, alkaloids, most saponins and some glycosides |

| 90% | Resins and oleoresins |

On the other hand, the following observations need to be considered:

• The evidence from phytochemical analysis that fresh plant tinctures contain better levels of active components than dried plant tinctures is generally lacking. In fact, fresh plant tinctures are usually prepared in a low alcohol environment (see below), which means that some less polar (more lipophilic) components may be only poorly extracted. Furthermore, the enzymatic activity of the plant material may not be inhibited in this low alcohol environment, meaning that key phytochemicals may actually be decomposed during the maceration process. This fact was dramatically illustrated by Bauer who found that cichoric acid in fresh plant preparations of Echinacea purpurea was largely decomposed by enzymatic activity.30 So what can be found in the living Echinacea plant was not preserved in the fresh plant tincture.

• Fresh plant tinctures were never official. While fresh plant preparations were included in homeopathic pharmacopoeias (given the energetic considerations in homeopathy this is understandable), they were never listed in conventional pharmacopoeias, other than a few entries for stabilised fresh juices known as succi (singular: succus). Hence, the use of a wide range of fresh plant tinctures is travel into unknown territory.

• Because of the water content of fresh plant tinctures, it is difficult to make preparations which are stronger than a 1:5 on a dry weight basis. This can be readily illustrated by the following example. A leafy, fresh plant material typically contains 80% moisture. Therefore, 100 g of this material represents 20 g of dried herb. To make a 1:5 tincture, this 20 g equivalent of dried herb must be mixed with 100 mL of liquid menstruum. But there is already 80 mL of water from the herb itself. So to preserve the 1:5 ratio only 20 mL of 96% ethanol can be added. This 20 mL of ethanol is not enough to extract the bulky 100 g of fresh plant material. But what is probably just as detrimental is that the effective ethanol percentage is only 20% (20 mL of ethanol and 80 g (or mL) of water from the fresh plant). This is too low to extract lipophilic components and barely enough to preserve the tincture. Some authors suggest the use of multiple macerations to overcome this problem, where the resultant tincture is macerated with a new batch of fresh herb, but this only makes the situation worse, diluting the alcohol to below the level that can stabilise the final tincture.

Standardised extracts

Issues and terminology

Extract or concentration ratio

The extract or concentration ratio is the ratio of the starting herbal raw material to the resultant finished concentrated extract. The finished extract is always expressed as the 1 and comes second. Thus, 10:1 means 10 kg of dried herb is used to produce 1 kg of extract.

Active compounds or constituents

Such a dilemma supports the basic premise of herbalists that the true active component is the herbal extract itself. Nonetheless, it is also likely that an extract low in marker compounds, which from pharmacological experiments have been found to have some relevant activity, will be less likely to confer a therapeutic effect and hence be poorer quality.

Types of standardised extracts

These types of extracts progressively represent a transition from a more traditional herbal product through to more modern types of products, which can be called phytopharmaceuticals. Phytopharmaceuticals are not like conventional drugs, but they are also very different from galenical extracts. Practitioners will wish to choose, based on their philosophical perspective, whether the use of phytopharmaceuticals is acceptable to them. However, as part of this process they should consider that phytopharmaceuticals are often chemically complex (an important criterion for phytotherapy), clinically proven and very safe. Probably, as suggested earlier, the decision is best based on a case-by-case basis.

Highly concentrated extracts

• Extraction with solvents different to ethanol-water mixtures such as acetone, chloroform, liquid carbon dioxide or hexane, etc

• Multiple solvent extraction steps (involving ethanol-water mixtures and/or other solvents such as those listed above)

• Standard chemical isolation techniques such as chromatography columns, ion-exchange resins, precipitation and so on.

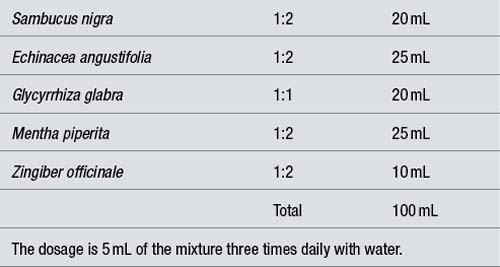

A mechanism for formulating liquids

Assuming the patient is to take 5 mL of a liquid formulation three times daily, this amounts to 105 mL per week which can be rounded down to 100 mL. Hence the weekly dosages of the individual herbs in a formulation should total 100 mL. If the total amount of herbs in a formula is less than 100 mL, water or aqueous ethanol can be added to bring the volume to 100 mL. Using this system the patient then automatically receives the correct amount of each herb in each dose, provided they take 5 mL three times a day (see Table 6.6).

Even using 1:1 and 1:2 extracts, formulations based on 100 mL for 1 week should not contain more than about six to seven herbs. Otherwise, therapeutic doses will not be achieved. If more than this number of herbs is required then the week’s formulation should be based on 150 mL. The single dose becomes 7.5 mL (which can be rounded up to 8 mL) three times daily.

References

1. Bensky D, Gamble A. Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica. Seattle: Eastland Press, 1986.

3. British Herbal Pharmacopoeia. Bournemouth: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1983.

4. British Pharmaceutical Codex. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 1934.

5. Nadkarni KM, Nadkarni AK. Indian Materia Medica. Bombay: Popular Prakashan Private Ltd, 1976.

6. Griggs B. Green Pharmacy. London: Jill Norman and Hobhouse, 1981.

9. British Herbal Medicine Association. British Herbal Compendium. Bournemouth: BHMA. 1992. p. 1.

10. British Herbal Medicine Association. British Herbal Compendium. Bournemouth: BHMA; 2006. p. 2.

11. Eberwein E, Vogel G. Arzneipflanzen in der Phytotherapie. Bonn: Kooperation Phytopharmaka, 1990.

16. Scudder JM. Specific Medication and Specific Medicines. Cincinnati: Scudder Bros Co., 1913.

19. Deutsches Arzneibuch der BRD, 7 Ausgabe; 1968.

24. Bellamy D, Pfister A. World Medicine: Plants, Patients and People. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

25. Reuben A. Wine hath drowned more men than the sea. Hepatology. 2002;36(2):516–518.