Doppler Imaging of the Prostate

Indications

The most important use of colour Doppler imaging of the prostate remains as an aid in cancer detection. This is particularly relevant in patients in whom cancer is suspected based on prostate specific antigen (PSA) elevation without obvious tumour on grey scale imaging. Other uses for Doppler imaging are largely confined to detection of prostatitis and inflammatory conditions. Controversy continues surrounding diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. This is largely attributable to the wide range of biological behaviour found with this disease. Up to 30% of 80-year-old males will have histological evidence of prostate cancer, yet most will die from other causes. Unfortunately, a more aggressive subset remains an important cause of mortality among men, with 33,720 deaths expected in the USA in 2011.1

Anatomy

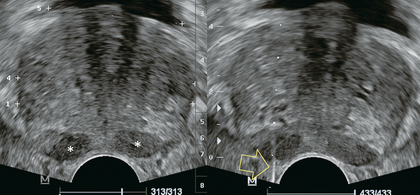

The prostate lies immediately anterior to the rectum and inferior to the bladder. Prostatic zonal anatomy has been extensively described by McNeal.2 In summary, the prostate is composed of three major zonal areas; the peripheral zone, the central zone and the transition zone (Fig. 11-1).

FIGURE 11-1 Axial ultrasound of the prostate in a normal patient. Note peripheral zone (*) separated from the more centrally oriented, periurethral, transition zone by the surgical capsule (open arrows).

PROSTATE VASCULAR ANATOMY

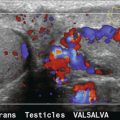

The prostate is supplied from two arterial sources: the prostatic arteries and the inferior vesical arteries, both arising from the internal iliac system. The prostatic arteries enter the prostate from an anterolateral location on each side, and give off capsular branches as well as urethral branches. Capsular arteries course along the lateral margin of the prostate, and give off numerous perforating branches which penetrate the capsule and supply approximately two-thirds of the total glandular tissue. The areas of penetration into the capsule are commonly referred to as the neurovascular bundles (Fig. 11-2).

FIGURE 11-2 Axial image of the left neurovascular bundle. Note left neurovascular bundle (arrow) with perforating branches penetrating into the prostate.

The inferior vesical arteries run along the inferior surface of the bladder and also provide urethral branches. In addition to supplying the central portion of the prostate, the inferior vesical arteries also give off branches which supply the bladder base, seminal vesicles and distal ureters (Fig. 11-3).3,4

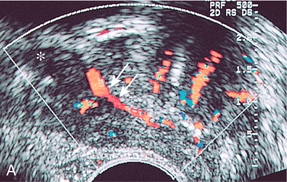

FIGURE 11-3 (A) Sagittal image of the prostate at the level of the seminal vesicle (*) demonstrates periurethral flow (arrows) originating from the inferior vesicle artery. (B) Axial power Doppler image at the level of the mid prostate demonstrates branches of the inferior vesical artery (open arrow) supplying urethra and surgical capsule.

Both the capsular and urethral branches can be visualised with colour Doppler ultrasound. In the absence of inflammation, neoplasm or hypertrophy, the normal prostate is expected to have low-level periurethral and pericapsular flow, with only a low level of flow in the prostatic parenchyma.5

Equipment and Technique

No specific patient preparation is required although some centres will give the patient a pre-examination enema and have them empty their bladder. The patient is generally placed in the left lateral decubitus position, and the knees brought up to the chest. A digital rectal examination is recommended prior to probe insertion to rule out any obstructing pathology and also to allow the examiner to evaluate the prostate by digital examination. The probe is covered with a condom into which coupling gel has been placed, and the probe lubricated and gently inserted into the rectal canal. Examination of the prostate by grey scale imaging is first performed, and the length, width and height of the gland measured. The prostatic volume is calculated based on the formula for a prolate ellipsoid (length × width × height × 0.523); this allows correlation of the measured PSA with a predicted PSA based on gland volume. Normal prostatic tissue produces approximately 0.3 ng/cc of PSA, whereas cancerous tissue produces approximately 3.0 ng/cc of PSA. Normal levels for polyclonal assays are typically defined as < 4.0 ng/mL; unfortunately, up to 20% of prostatic cancers present in patients with ‘normal’ levels of PSA. A ‘predicted’ PSA can be generated based on the patient’s gland volume × 0.2 for polyclonal assays (or gland volume × 0.1 for monoclonal assays). A level of measured PSA that exceeds predicted PSA increases the suspicion of cancer and increases the positive predictive value of prostatic biopsy.6

Most prostate cancers (70%) arise in the peripheral zone, with a minority originating in the central (10–15%) and transition zones (10–15%). Because of this, it is very important that the sonographer carefully examine the peripheral zone for signs of tumour. Virtually all prostate cancers will be hypoechoic in relation to normal peripheral zone tissues (Fig. 11-4), although a minority of cribriform carcinomas can demonstrate punctate calcifications.

Colour Doppler of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer arises in both the outer (peripheral zone) and central gland (transition zone). Cancers in these two locations have different imaging characteristics and biologic behaviour7 and thus will be considered separately.

Outer gland (peripheral zone) cancer: Tumours arising in the peripheral zone tend to be isoechoic at grey scale imaging with the background normal prostate (Fig. 11-4). As the tumours enlarge, they become progressively more hypoechoic, and thus become more apparent by ultrasound (Fig. 11-5).

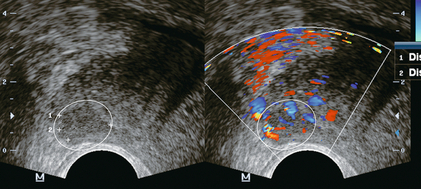

FIGURE 11-5 Peripheral zone prostate cancer. Grey scale image (left) demonstrates the hypoechoic prostate cancer (calipers) in the region of the right neurovascular bundle. Color Doppler image at the same level demonstrates increased vascularity in the tumour (encircled).

Large tumours are usually more de-differentiated with a higher Gleason score. Focal areas of calcification may develop in regions of necrosis. As tumours further increase in size, the risk of extra-capsular extension also increases. Above approximately 1.5 cm in diameter areas of anatomic weakness should be carefully surveyed, including the seminal vesicles, neurovascular bundles, and the apical capsule. Targeted biopsies through these regions can increase the specificity of diagnosis for extra-capsular extension of tumour.8 As peripheral zone tumours enlarge the degree of microvascular density also increases. In general, these larger tumours are therefore more vascular and demonstrate increased colour Doppler signal.

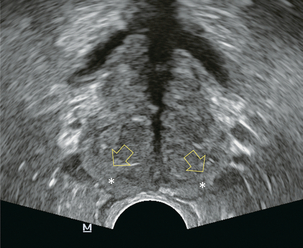

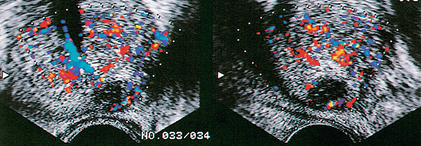

Inner gland (transition zone) cancer: Transition zone cancers are biologically different to peripheral zone tumours. In general, they are associated with favourable pathologic features, and are less likely to present with early extra-capsular extension. Large-volume transition zone cancers are often associated with low Gleason scores.7 Cancers that arise in the transition zone are more difficult to detect with ultrasound because of the heterogeneous nature of the background tissue. ‘Normal’ transition zone tissue is of mixed echogenicity and may contain cysts and calcified foci. Similar to peripheral zone tumours, transition zone cancer is generally hypoechoic and demonstrates increased vascularity at colour Doppler imaging (Fig. 11-6),7 but because of the heterogeneous background of the transition zone, central cancer can be difficult to detect with grey scale imaging alone.

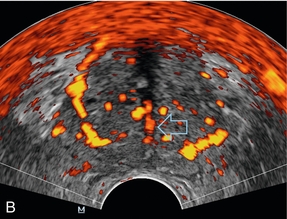

FIGURE 11-6 Transition zone (central gland) prostate cancer. Axial images demonstrate a hypoechoic mass on grey scale ultrasound (calipers) with hypervascularity on power Doppler images (encircled).

For a high-risk patient (based on PSA) in whom a peripheral tumour has not been found, a careful examination of the transition zone should be undertaken. For these patients, colour Doppler has been shown to be most useful.9 Areas of increased colour Doppler signal can be targeted for biopsy with increased positive biopsy rates, but it is controversial as to whether targeted biopsies guided by colour Doppler imaging can replace sextant biopsies.10–12 Biopsy of areas of increased colour signal when no other sites of cancer have been found can be particularly useful in black males, where the positive predictive value for biopsy based on Doppler findings has been found to be twice that of white males (32.2% vs. 13.5% respectively).13 There is currently no consensus regarding the use of ultrasound contrast agents in prostate imaging.14,15 Likewise, spectral Doppler has limited utility in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. While most tumours demonstrate a low resistance waveform (high diastolic flow), this is not a specific finding and does not separate cancer from inflammation.

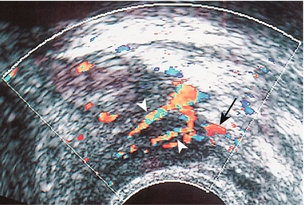

Colour Doppler of Prostatic Inflammatory Disease

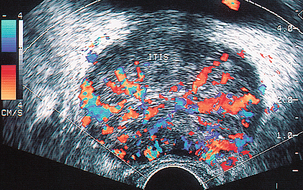

Prostatitis is a difficult condition to diagnose and treat. There are several aetiologies of prostatitis, ranging from bacterial to non-bacterial causes. In the case of bacterial prostatitis, the offending organism is usually Escherichia coli or other urinary tract pathogens. Grey scale findings of acute prostatitis include an hypoechoic rim around the prostate or periurethral areas, and low-level echogenic areas within the prostate.16 Colour Doppler is useful in cases of diffuse bacterial prostatitis. The severity of the inflammatory reaction is mirrored by focal or diffuse increase in the colour signal in the prostatic parenchyma.17,18 When focally increased colour signals are seen in cases of prostatitis, there is no reliable non-invasive method to differentiate inflammation from tumour.17 However, cases of grossly increased flow spread diffusely throughout the gland should be considered prostatitis in the appropriate clinical setting (Fig. 11-7). When the inflammatory process continues to suppuration, a prostatic abscess can develop. On ultrasound, this is seen as a cavity filled with low-level echoes from debris (Fig. 11-8).19 Colour Doppler may detect increased flow around the rim of the cavity, although this finding is not necessary to make the diagnosis. Cases of bacterial prostatitis are treated by antibiotics, whereas prostatic abscess requires transrectal catheter or transurethral drainage with unroofing of the abscess cavity.

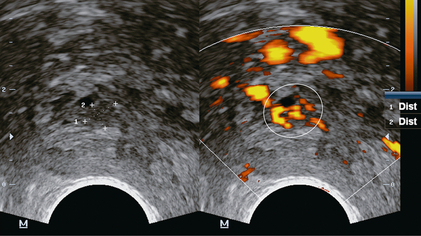

FIGURE 11-7 Prostatitis. Colour Doppler image of diffuse prostatitis demonstrates grossly increased flow throughout the gland.

FIGURE 11-8 Prostatic abscess. Markedly hypoechoic lesion with subtle through transmission is present in the peripheral zone of this patient. Note lack of flow in the central portion of this lesion, a finding that would be very unusual for prostate cancer. Drainage confirmed the presence of an abscess.

REFERENCES

1. Siegel, R., Ward, E., Browley, O., et al. Cancer Statistics 2011. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011; 61:212–236.

2. McNeal, J. E. Regional morphology and pathology of the prostate. Am J Clin Pathol. 1968; 49:347–357.

3. Flocks, R. H. The arterial distribution within the prostate gland: its role in transurethral prostatic resection. J Urol. 1937; 37:524–548.

4. Clegg, E. J. The arterial supply of the human prostate and seminal vesicles. J Anat. 1955; 89:209–217.

5. Neumaier, C. E., Martinoli, C., Derchi, L. E., et al. Normal prostate gland: examination with colour Doppler US. Radiology. 1995; 196:453–457.

6. Lee, F., Littrup, P. J., Loft-Christensen, L., et al. Predicted prostate specific antigen results using transrectal ultrasound gland volume: Differentiation of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Cancer. 1992; 70:211–220.

7. Lee, F., Siders, D. B., Torp-Pedersen, S., et al. Prostate cancer: Transrectal ultrasound and pathology comparison–A preliminary study of outer gland (peripheral and central zones) and inner gland (transition zone) cancer. Cancer. 1991; 67:1132.

8. Lee, F., Bahn, D. K., Siders, D. B., et al. The role of TRUS-guided biopsies for determination of internal and external spread of prostate cancer. Semin Urol Oncol. 1998; 16:129–136.

9. DeCarvalho, V. S., Soto, J. A., Guidone, P. L., et al. Role of colour Doppler in improving the detection of cancer in the isoechoic prostate gland (abstr). Radiology. 1995; 197(P):365.

10. Halpern, E. J., Frauscher, F., Strup, S. E., et al. Prostate: high-frequency Doppler US imaging for cancer detection. Radiology. 2002; 225:71–77.

11. Inahara, M., Suzuki, H., Nakamachi, H., et al. Clinical evaluation of transrectal power Doppler imaging in the detection of prostate cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004; 36:175–180.

12. Del Rosso, A., Di Pierro, E. D., Masciovecchio, S., et al. Does transrectal colour Doppler ultrasound improve the diagnosis of prostate cancer? Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2012; 84:22–25.

13. Littrup, P. J., Klein, R. M., Sparschu, R. A., et al. Colour Doppler of the prostate: histologic and racial correlations (abstr). Radiology. 1995; 197(P):365.

14. Frauscher, F., Klauser, A., Halpern, E. J., et al. Detection of prostate cancer with a microbubble ultrasound contrast agent. Lancet. 2001; 357:1849–1850.

15. Bogers, H. A., Sedelaar, J. P., Beerlage, H. P., et al. Contrast-enhanced three-dimensional power Doppler angiography of the human prostate: correlation with biopsy outcome. Urology. 1999; 54:97–104.

16. Griffiths, G. J., Crooks, A. J. R., Roberts, E. E., et al. Ultrasonic appearances associated with prostatic inflammation: A preliminary study. Clin Radiol. 1984; 35:343–345.

17. Patel, U., Rickards, D. The diagnostic value of colour Doppler flow in the peripheral zone of the prostate, with histological correlation. Br J Urol. 1994; 74:590–595.

18. Palmas, A. S., Coelho, M. F., Fonseca, J. F. Colour Doppler ultrasonographic scanning in acute bacterial prostatitis. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2010; 82:271–274.

19. Lee, F. T., Jr., Lee, F., Solomon, M. H., et al. Ultrasonic demonstration of prostatic abscess. J Ultrasound Med. 1986; 5:101–102.