Chapter 47 Does the Type of Hospital in Which a Patient Is Treated Affect Outcomes in Orthopaedic Patients?

Although healthcare systems differ around the world, there is currently nearly universal political and financial pressure for change to create greater efficiencies in delivery while maintaining favorable patient outcomes. Hospitals are an important part of the healthcare system, and the services and quality of care in different types of hospitals are currently the subject of much debate.1,2

Hospitals can be broadly classified by their teaching status (teaching or nonteaching), funding status (for-profit or not for-profit), or ownership (public or private),1,2 or in some jurisdictions, by their specialty services (orthopedic, cardiovascular, etc.).3

Evidence has been reported that the type of hospital in which a patient is treated can affect both his or her outcome and healthcare costs.1,4 This is an important issue that could have a large impact on health policy decisions at the government and hospital levels. Unfortunately, a paucity of evidence exists in the literature in general and in the orthopedic literature in particular to inform this debate.

EVIDENCE

Several issues must be considered to resolve these questions, with the major one being the considerable heterogeneity of studies with respect to diseases and procedures, risk adjustment, types of data, and settings.2,5

Studies report outcomes for patients with a variety of conditions; however, most studies are on cardiovascular disease, mainly congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or stroke.3,4,6–9 Only five studies included patients undergoing orthopedic procedures, and these were in patients who had received surgery for total joint replacement10 or hip fractures.4,7, 11, 12 No studies of outcome in patients with fractures as a result of major trauma have been reported.

No randomized, controlled trials have been identified, and it is unlikely that this will happen in the future. All studies have been observational because this is the most feasible design to address these questions.1 Although this level of evidence may be considered weak, a well-conducted observational study can contribute valuable information. Many studies are retrospective cohort studies, a relatively robust observational design, not as subject to bias as some other study designs, and these have an important part to play in medical research.13 The main concern with cohort studies is residual confounding by unmeasured variables related to the patients and the outcome. This is problematic with the use of administrative data, because usually only demographic information and some measures of comorbidities are available for risk adjustment in the analyses.

Nearly all of the evidence available is based on either clinical chart reviews or administrative data.2 Because administrative data are collected for billing, rather than research purposes, problems with coding are an issue.14 These problems may differ among databases. Nevertheless, although those such as the Health Care Financing Administration data, which has been used in many U.S. studies,7,10, 15 and the Canadian Institutes of Health Information data, which has been used in many Canadian studies,11,16, 17 have been validated,14,18 to some extent, this remains a problem inherent in all studies. The administrative data in the U.S. studies are mainly for Medicare patients,4,10 and this could introduce some bias, if these patients are older and sicker than the average patient. This is less of a problem in countries with universal healthcare, such as Canada, where administrative databases contain information on all patients.

Another challenge in evaluating the evidence is that most of the studies that examine these issues have been done in the United States, where the hospital system is more complex, compared with Canada, for example. In the United States, all teaching hospitals are not-for-profit; however, nonteaching hospitals can be either for-profit or not-for-profit. Thus, the issue of whether teaching hospitals are different from nonteaching hospitals may be confounded by their funding status (for-profit or not for-profit). For example, some studies have compared not-for-profit teaching hospitals with not-for-profit nonteaching hospitals,11 whereas others have compared not-for-profit teaching hospitals with for-profit nonteaching hospitals.4 This could lead to inconsistent conclusions.

Two recent meta-analyses have attempted to resolve the questions of whether outcomes are better in teaching hospitals versus nonteaching hospitals2 and whether mortality rates differ between private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals.1

The first analysis identified 132 eligible studies that included 93 on mortality and 61 on other outcomes.2 Twenty-two of these assessed both. A wide range of patient groups were represented by these studies; most were patients with cardiovascular disease, and only two involved orthopedic patients. Most studies were done in U.S. hospitals. Ten studies were done in Canada, 9 in the United Kingdom, 4 in Norway, and 12 in other countries. Using all adjusted mortality data, the authors report a relative risk (RR) for teaching hospitals of 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93–1.00). Subgroup analyses involving data sources (clinical or administrative) and location of study (United States or other) yielded no important differences. The authors report some evidence that teaching hospitals performed better for certain diagnoses (breast cancer, cerebrovascular accidents, and mixed diagnoses). Because of the small numbers of studies, no information could be calculated for orthopedic procedures. This was an extensive and thorough meta-analysis that suggests that differences between teaching and nonteaching hospitals are minimal.

The second meta-analysis by Devereaux and colleagues1 compares mortality rates between private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. Fifteen studies were included in this analysis. In an attempt to remove hospital teaching status as a confounding influence, they included results from for-profit nonteaching and not-for-profit teaching hospitals when they were available. They also avoided adjusting for variables under the control of hospital administrators that could be influenced by a profit motive and affect mortality, such as nursing staffing levels. Three of the studies in their analysis included orthopedic patients (hip fractures, lower extremity fractures, hip replacement).7,10, 15 One of the three included all patients in the dataset but did not differentiate diagnoses in the analysis.15 They reported a RR for for-profit hospitals of 1.020 (95% CI, 1.003–1.038). These results also suggest minimal differences between private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals.

The evidence for a difference between rural or urban hospitals is even more tenuous, because few studies are reported in the literature. Keeler and coauthors7 reviewed the medical records of 14,008 patients aged 65 years or older in 297 hospitals in the United States and compared them with mortality data from an administrative database. Patients had either congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, AMI, pneumonia, or hip fracture; however, subgroup analyses on each diagnosis were not reported. Their results, adjusted for comorbidities, showed that rural hospitals consistently provided belowaverage care, and patients treated there had a slightly increased chance of dying compared with the average for all hospitals. Patients treated in larger urban hospitals, including teaching hospitals, had a slightly smaller chance of dying.

Another study of patients with heart failure in Germany found that adherence to heart failure guidelines was less in rural hospitals; however, there was no significant difference in mortality after adjustment for age and sex.3

A Canadian study11 found a trend to increased mortality at 3, 6, and 12 months after hip fracture surgery in rural hospitals compared with urban community hospitals; however, this did not reach statistical significance. This study is discussed in greater detail in the next section.

In contrast, Glenn and Jijon19 found that riskadjusted death rates for small hospitals with unspecialized services were similar between urban and rural areas,19 leading the authors to conclude that small rural hospitals make appropriate decisions to transfer severely ill patients and provide quality care for retained patients.

Some evidence does show that delay to surgery for fractures resulting from major trauma is related to a poorer outcome.20–22 One study that took place in a rural trauma center found an incidence of delay to diagnosis of 3%, and that this was related to patient outcome. Whether this accounts for some of the differences observed between urban and rural institutions remains to be determined.

EVIDENCE IN ORTHOPEDIC PATIENTS

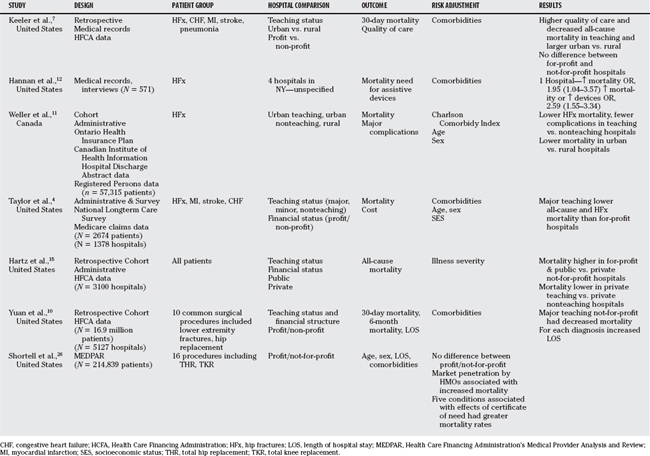

A consistent theme in this chapter is the lack of evidence in orthopedic patients. The studies that have been reported are summarized in Table 47-1. One did not specify hospital type.12 Hip fractures were included in the sample of another study, but no subgroup analyses were presented.7

Yuan and coworkers10 studied the association between hospital type and mortality and length of stay in 16.9 million Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Hospitals were categorized as for-profit, not-for-profit, osteopathic, public, teaching not-for-profit, and teaching public. They report results, adjusted for comorbidities associated with mortality, for nonspecified lower extremity fractures and hip replacements separately. No differences among hospitals were found for lower extremity fractures; however, they report in the text that mortality rates for hip replacement were greater at teaching not-for-profit hospitals than at for-profit, not-for-profit, and public hospitals. Unfortunately, the graphs presented indicate the opposite; therefore, it is not possible to interpret their data.

Two studies have examined mortality in hip fracture patients, one in the United States4 and one in Canada.11 Both studies use administrative data.

Taylor and investigators4 used the National Long Term Care Survey, which was representative of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States 65 years or older, linked to Medicare claims data, to study the relation of hospital type to outcome in 3206 patients with hip fracture, stroke, coronary heart disease, or congestive heart failure. Hospitals were classified according to teaching status (major or minor) and ownership using the American Hospital Association’s annual hospital survey. Comorbid conditions were assessed using the Hierarchical Coexisting Conditions DxCG model.24

The hazard ratio of mortality after hip fracture at major teaching hospitals was 0.54 (95% CI, 0.37–0.79). Moreover, a gradient of decreasing risk was noted through the categories of for-profit nonteaching hospitals, government, nonprofit, minor teaching and major teaching hospitals. The results for the cardiovascular disease diagnoses were much less striking (stroke: hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.64–1.24; P = 0.49; coronary heart disease: hazard ratio, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.55–1.07; P = 0.11; congestive heart failure: hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.64–1.41; P = 0.81) and were similar to results reported from the meta-analysis reported by Papanikolaou and colleagues.2

In a Canadian study by Weller and coworkers,11 57,315 patients with hip fracture aged 50 years or older were identified from the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstracts Database. The modified Charlson–Deyo index, a well-validated scale that can be calculated from administrative data, was used to adjust for comorbidity.25 Hospitals were classified as teaching or nonteaching. Nonteaching (community) hospitals were further classified as urban (located in communities with population ≥ 10,000) or rural (located in communities with population ≤ 10,000). The cohort was linked to a registry containing information on all deaths in Ontario.

Teaching hospitals in the United States are not-for-profit institutions and were compared with private for-profit hospitals in the U.S. study, suggesting that a profit motive may explain the strong association observed in the patients with hip fracture. Nevertheless, a profit motive cannot explain the outcomes observed in the Canadian study because 95% of Canadian hospitals are private not-for-profit institutions.1 The difference in the strength of the association observed in the U.S. data (OR, 0.54)4 compared with the Canadian study (ORs ranging from 0.86–0.89) suggests that, although a profit motive may be the most important factor in explaining the increased mortality observed in for-profit hospitals, other hospital characteristics may also play a role in patients with hip fracture.

It is interesting that the results for breast cancer and cerebrovascular accident in the meta-analysis by Papanikolaou and colleagues2 were similar in magnitude and significance to those observed for hip fracture (breast cancer: OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78–0.93; cerebrovascular accident: OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90–0.99), whereas those for heart disease outcomes other than stroke are similar to the overall ORs. Perhaps because the heart disease studies predominate, they are masking relations for other conditions.

GUIDELINES

Insufficient evidence is available to inform health policy and system-wide decisions.

More advanced statistical methods such as hierarchical modeling may help clarify some of the questions around clustering of certain types of patients in particular hospitals and regions. The use of propensity scores would also help in the interpretation of the data. Table 47-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

| RECOMMENDATION | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Devereaux PJ, Choi PTL, Lacchetti C, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:1399-1406.

2 Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, Ioannidis JP. Patient outcomes with teaching versus nonteaching healthcare: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e341.

3 Taubert G, Bergmeier C, Andresen H, et al. Clinical profile and management of heart failure: Rural community hospital vs. metropolitan heart center. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:611-617.

4 Taylor DH, Whellan DJ, Sloan FA. Effects of admission to a teaching hospital on the cost and quality of care for medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:293-299.

5 Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS. Teaching hospitals and quality of care: A review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2002;80:569-593. v

6 Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Weissman NW, et al. Relationship of hospital teaching status with quality of care and mortality for Medicare patients with acute MI. JAMA. 2000;284:1256-1262.

7 Keeler EB, Rubenstein LV, Kahn KL, et al. Hospital characteristics and quality of care. JAMA. 1992;268:1709-1714.

8 Polanczyk CA, Lane A, Coburn M, et al. Hospital outcomes in major teaching, minor teaching, and nonteaching hospitals in New York State. Am J Med. 2002;112:255-261.

9 Rosenthal GE, Harper DL, Quinn LM, Cooper GS. Severity-adjusted mortality and length of stay in teaching and nonteaching hospitals. Results of a regional study. JAMA. 1997;278:485-490.

10 Yuan Z, Cooper GS, Einstadter D, et al. The association between hospital type and mortality and length of stay: A study of 16.9 million hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2000;38:231-245.

11 Weller I, Wai EK, Jaglal S, Kreder HJ. The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:361-366.

12 Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, et al. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285:2736-2742.

13 Doll R. Cohort studies: History of the method. II. Retrospective cohort studies. Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46:152-160.

14 Fisher ES, Whaley FS, Krushat WM, et al. The accuracy of Medicare’s hospital claims data: Progress has been made, but problems remain. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:243-248.

15 Hartz AJ, Krakauer H, Kuhn EM, et al. Hospital characteristics and mortality rates. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1720-1725.

16 Alter DA, Austin PC, Tu JV. Community factors, hospital characteristics and inter-regional outcome variations following acute myocardial infarction in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:247-255.

17 Alter DA, Tu JV, Austin PC, Naylor CD. Waiting times, revascularization modality, and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction at hospitals with and without on-site revascularization facilities in Canada. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:410-419.

18 Hawker GA, Coyte PC, Wright JG, et al. Accuracy of administrative data for assessing outcomes after knee replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:265-273.

19 Glenn LL, Jijon CR. Risk-adjusted in-hospital death rates for peer hospitals in rural and urban regions. J Rural Health. 1999;15:94-107.

20 Naique SB, Pearse M, Nanchahal J. Management of severe open tibial fractures: The need for combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical treatment in specialist centres. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:351-357.

21 Solan MC, Molloy S, Packham I, et al. Pelvic and acetabular fractures in the United Kingdom: A continued public health emergency. Injury. 2004;35:16-22.

22 Bircher M, Giannoudis PV. Pelvic trauma management within the UK: A reflection of a failing trauma service. Injury. 2004;35:2-6.

23 Tepper J, Pollett W, Jin Y, et al. Utilization rates for surgical procedures in rural and urban Canada. Can J Rural Med. 2006;11:195-203.

24 Ellis RP, Pope GC, Iezzoni L, et al. Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare capitation payments. Health Care Financ Rev. 1996;17:101-128.

25 Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613-619.

26 Shortell SM, Hughes EFX. The effects of regulation, competition, and ownership on mortality rates among hospital inpatients. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1100-1107.