Dizziness and Vertigo

Perspective

Dizziness is an extremely common yet complex neurologic symptom that reflects a disturbance of normal balance perception and spatial orientation. An estimated 7.5 million patients with dizziness are seen each year in ambulatory care settings.1 Dizziness is also one of the most common principal complaints in the emergency department (ED) and is responsible for 2.5% of all ED visits.2 Among patients older than 60 years, 20% have experienced dizziness severe enough to affect their daily activity.3

“Dizziness” is an imprecise descriptor. Patients use the term to describe a variety of experiences, including sensations of motion, weakness, lightheadedness, unsteadiness, and depression. Even clinical experts do not uniformly agree to precise definitions, with some defining it broadly and others more narrowly. Dizziness is historically categorized into one of four categories based on symptom quality: vertigo (illusion of motion, often spinning), near syncope (feeling of impending faint), disequilibrium (loss of equilibrium when walking), and nonspecific dizziness.4

Dizziness can be caused by a myriad diseases. In older persons it is associated with a variety of cardiovascular, neurosensory, and psychiatric conditions and with the use of multiple medications.5 The challenge for the emergency physician is to sift out the rare patient with a dangerous underlying disorder from the many others who have benign causes.

Diagnostic Approach

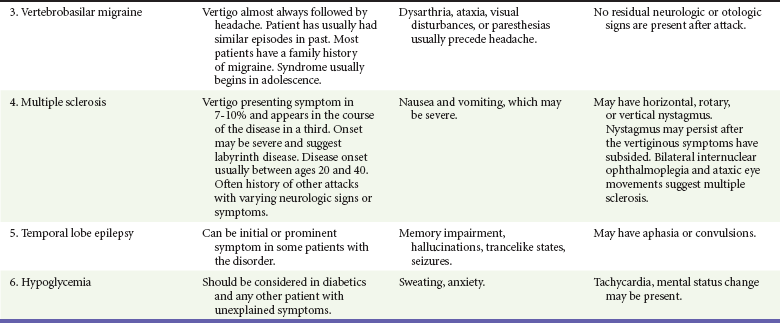

It is often helpful to have dizzy patients describe the sensation they are experiencing without using the word dizzy. When this is done, one can generally categorize the dizziness into one of four categories: vertigo, near syncope, disequilibrium, and nonspecific dizziness. Vertigo is an illusion of motion, classically described as the room spinning. Some further subdivide this into objective vertigo (external environment is spinning) and subjective vertigo (spinning of self). Near syncope is usually described as feeling faint or lightheaded. Disequilibrium is usually described as an unsteady gait. Nonspecific dizziness is generally thought to be related to anxiety. The validity of this symptom-oriented method of categorizing dizziness has been recently challenged.6 For some patients, dizziness is simply a metaphor for malaise, representing a variety of causes, such as anemia, viral illness, or depression. The primary focus of this chapter is to provide a framework to differentiate vertigo from other types of dizziness and to identify potentially life-threatening causes of these symptoms.

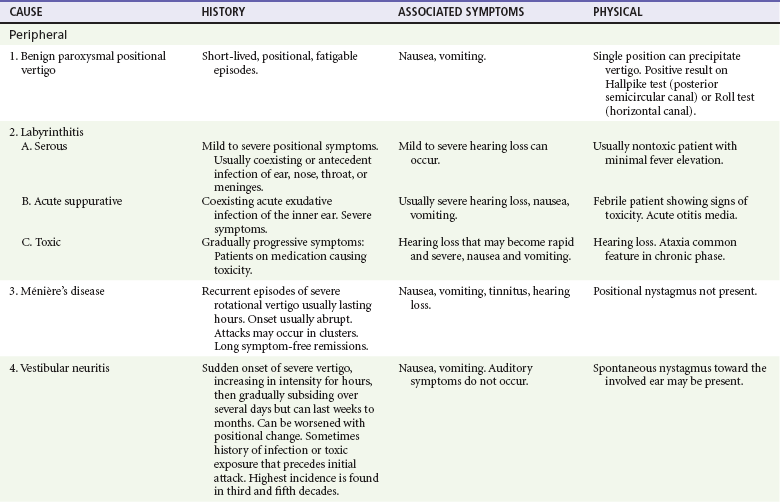

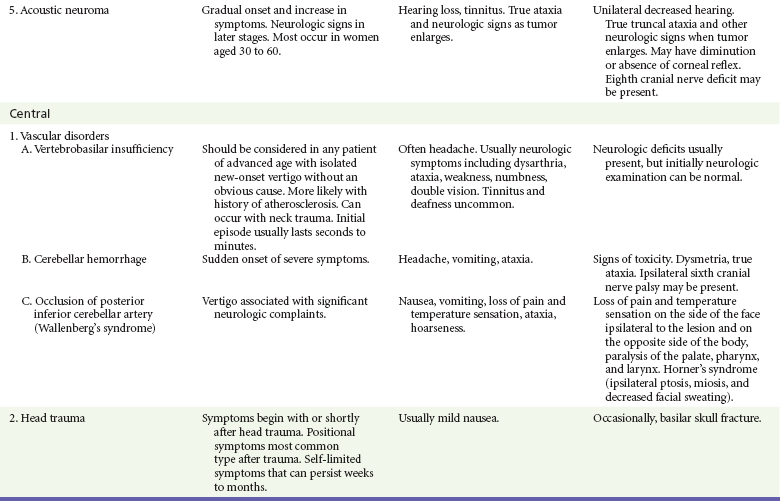

If the patient has true vertigo, the clinician should determine whether the cause is a peripheral lesion, such as from the vestibular system, or a central process, such as cerebrovascular disease or a neoplasm. In most cases, peripheral disorders are benign, whereas central disorders have more serious consequences. Occasionally, as in the case of a cerebellar hemorrhage, immediate therapeutic intervention is indicated. Acute suppurative labyrinthitis is the only cause of peripheral vertigo that requires urgent intervention. Box 19-1 lists causes of vertigo and identifies the peripheral, central, and systemic diagnoses. Table 19-1 summarizes the different characteristics of peripheral and central vertigo.

Table 19-1

Characteristics of Peripheral and Central Vertigo

| CHARACTERISTIC | PERIPHERAL | CENTRAL |

| Onset | Sudden | Gradual or sudden |

| Intensity | Severe | Mild |

| Duration | Usually seconds or minutes; occasionally hours, days (intermittent) | Usually weeks, months (continuous) but can be seconds or minutes with vascular causes |

| Direction of nystagmus | One direction (usually horizontorotary) | Vertical, downbeating |

| Effect of head position | Worsened by position, often single critical position | Little change, associated with more than one position |

| Associated neurologic findings | None | Usually present |

| Associated auditory findings | May be present, including tinnitus | None |

Pivotal Findings

The medical history is used to determine if true vertigo exists. Although usually described as the environment spinning, any sensation of disorientation in space or sensation of motion can qualify as vertigo. Some nausea, vomiting, pallor, and perspiration accompany almost all but the mildest forms of vertigo. A sensation of imbalance often accompanies vertigo, and this can be extremely difficult to distinguish from true instability until after the patient’s symptoms have been reduced by treatment. True instability, disequilibrium, or ataxia indicates a higher likelihood of a central process.7 Because the labyrinth has no effect on the level of consciousness, the patient should not have an associated change in mentation or syncope.

Head injury can cause vertigo occasionally from intracerebral injury and more commonly from labyrinth concussion. Neck injury can cause vertigo from vertebral artery dissection, resulting in posterior circulation ischemia.8

Are there associated neurologic symptoms? The patient or family members should be questioned about the time of onset of ataxia or gait disturbances. Ataxia of recent and relatively sudden onset suggests cerebellar hemorrhage or infarction in the distribution of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery or the superior cerebellar artery. Ataxia that is slowly progressive suggests chronic cerebellar disorders. True ataxia may be difficult to discern from the unsteadiness that occurs when a patient with significant vertigo attempts to walk, though other findings such as nystagmus and dysmetria can often help narrow the differential diagnosis. The symptom of imbalance raises the likelihood of TIA and stroke. Isolated vertigo can be the only initial symptom of cerebellar and other posterior circulation bleeds, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and infarction.9,10 One study showed that emergency physicians often did not make the correct diagnosis in patients with validated strokes or TIAs whose presenting symptom was only vertigo.7 Identifying these individuals is a significant and important challenge for clinicians taking care of vertiginous patients. The vast majority of patients with isolated dizziness do not have TIA or stroke, but the risk of not identifying the few who do is significant for ultimate patient outcomes. Stroke has been seen in 3.2% of patients with dizziness syndrome, but only 0.7% of those with isolated dizziness had a stroke.7 A recent study also showed that fewer than 1 in 500 patients discharged with a diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo experienced a major vascular event in the month after discharge.11

Past Medical History.: Older age, male sex, hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation are examples of diseases that put patients at higher risk for TIA and stroke. It is important to identify what medications patients are taking, because many have direct vestibulotoxicity. The most commonly encountered are the aminoglycosides, anticonvulsants, alcohols, quinine, quinidine, and minocycline. Daily consumed substances such as caffeine and nicotine, which are not often thought of as medications, can have wide-ranging autonomic effects that may exacerbate vestibular symptoms.

Physical Examination

Vital Signs.: Presence of hypotension suggests near syncope as the cause of dizziness. When subclavian steal syndrome, which also can cause vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI), is suspected, the pulse and blood pressure should be checked on both sides.

Head and Neck.: Carotid or vertebral artery bruits suggest atherosclerosis and risk for TIA or stroke. The vertebral artery can be auscultated in the supraclavicular region.

The abnormal jerk nystagmus of inner ear disease consists of slow and quick components. The eyes slowly “drift” in the direction of the diseased, hypoactive ear, then quickly jerk back to the intended direction of gaze. Positional nystagmus, induced by changing the position of the head, strongly suggests an organic vestibular disorder, typically BPPV. Central nervous system causes of nystagmus are considered when the pattern of nystagmus is purely vertical, downbeating (fast phase beating toward the nose, or nonfatigable) or when the nystagmus is neither provoked nor relieved by repositioning maneuvers. The characteristics of nystagmus are one of the most valuable tools for distinguishing peripheral from central causes of vertigo (Table 19-2).

Table 19-2

Distinguishing Characteristics of Nystagmus with Central and Peripheral Vertigo

| CHARACTERISTIC | CENTRAL | PERIPHERAL |

| Direction | Can be any direction, downbeating (fast phase beats toward nose) | Horizontal or horizontorotary, upbeating (fast phase beats toward forehead) |

| Position testing effects | ||

| Latency | Short | Long |

| Duration | Sustained | Transient |

| Intensity | Mild | Mild to severe |

| Fatigability | Nonfatigable | Fatigable |

| Effect of visual fixation | Not suppressed, may be enhanced | Suppressed |

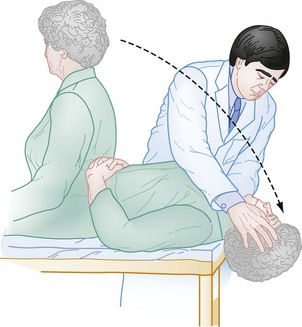

Positional Testing.: Positional testing can confirm the diagnosis of some causes of peripheral vertigo. The Hallpike test,12 also known as the Dix-Hallpike test or the Nylen-Barany test, confirms the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV. The head is turned 45 degrees to one side and then the patient is moved from an upright seated position to a supine position with the head overhanging the edge of the gurney (Fig. 19-1). The eyes are observed for nystagmus, and the patient is queried for the occurrence of vertigo. The patient is then brought back up to the seated position and the test is repeated with the head turned 45 degrees to the other side. In general, if the patient has posterior canal BPPV, only one side should be positive, and this indicates the involved side. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the patient can be treated with the Epley maneuver (see later). If the Hallpike test result is negative or seems to be positive bilaterally, one can use the roll test to test for the horizontal canal variant of BPPV. Unlike in the Hallpike test, the head does not need to overhang the edge of the gurney, and the patient will have reproduction of symptoms and horizontal nystagmus with the head turned in either direction. In the roll test the patient lies flat on the gurney (unlike the Hallpike test, the head does not need to overhang the edge of the gurney) and the examiner turns the patient’s head up to 90 degrees to one side. If the otoliths are located in the horizontal canal, the patient will develop vertigo and horizontal nystagmus. The examiner then turns the head to the other side. Again, if otoliths are located in the horizontal canal, the patient will develop vertigo and horizontal nystagmus (note that the direction of the nystagmus will change). Thus, unlike the patient with posterior canal BPPV, the patient with horizontal canal BPPV will have reproduction of symptoms and horizontal nystagmus with the head turned in either direction. The side that is involved is the one with the more violent symptoms and more dramatic nystagmus. The horizontal canal variant of BPPV can be treated with the “barbecue roll” (see later).

Figure 19-1 Testing for positional vertigo and nystagmus.

The head thrust, or head impulse test, is used to diagnose vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis.13 The physician stands face to face with the patient and places both hands on the sides of the patient’s head. The patient stares at the examiner’s nose while the examiner rapidly turns the patient’s head approximately 10 degrees to one side. Normally the patient’s eyes should keep focusing on the examiner’s nose. If there is a problem with the vestibular nerve, the eyes will temporarily move along with the head. A corrective saccade will then occur, in which the eyes jerk back toward the midline. If a saccade is seen, this denotes a positive head-thrust test result and indicates vestibular nerve dysfunction and confirms the diagnosis of vestibular neuritis.

Neurologic Examination.: The presence of cranial nerve deficits suggests a space-occupying lesion in the brainstem or cerebellopontine angle. The corneal reflex is a sensory cranial nerve V and motor cranial nerve VII circuit. Its diminution or absence can be one of the early signs of an acoustic neuroma, which is a slow-growing tumor of the vestibular-cochlear nerve (the eighth cranial nerve). Acoustic neuromas rarely manifest with vertigo and instead typically manifest with sensorineural hearing loss. The Rinne and Weber tests are used in patients with hearing loss. In the Rinne test, which tests for conductive hearing loss, a vibrating tuning fork is held against the mastoid bone. Once the patient can no longer hear the sound from the tuning fork, the tuning fork is moved toward the ear. If there is no conductive hearing loss, the patient will be able to hear the tuning fork. With acoustic neuroma, the result of the Rinne test is normal (the patient can still hear the tuning fork), though both air and bone conduction are reduced as compared with someone who does not have an acoustic neuroma. In the Weber test, which tests for sensorineural hearing loss, a vibrating tuning fork is held against the middle of the forehead. If there is no sensorineural hearing loss, the sound is heard equally in both ears. In patients with acoustic neuroma, the sound will localize to the normal ear. Seventh cranial nerve involvement (e.g., Bell’s palsy) causes facial palsy that affects the entire side of the face. In supranuclear facial paralysis, the forehead is spared because these muscles receive bilateral cortical innervation.

Ancillary Testing

Most routine laboratory testing is not helpful in the evaluation of a vertiginous patient except for a finger-stick blood glucose test.14 Blood counts and blood chemistries are sometimes helpful when it is difficult to distinguish whether “dizziness” is vertigo or near syncope. An electrocardiogram should be obtained if there is a possibility of myocardial ischemia or dysrhythmia.

Radiologic Imaging.: A cross-sectional study of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) suggests significant overuse of computed tomography (CT) in low-risk patients.15 Risk factor assessment and symptom patterns can be extremely helpful in deciding which patients warrant imaging and admission. Older age, male sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation put patients at higher risk for more serious causes of dizziness and vertigo.

If cerebellar hemorrhage, cerebellar infarction, or other central lesions are suggested, emergent CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is indicated. MRI, when available, has become the diagnostic modality of choice when cerebellar processes other than acute hemorrhage are possible. MRI is particularly useful for the diagnosis of acoustic neuromas and for sclerotic and demyelinating lesions of the white matter, as seen in multiple sclerosis. Acute vertigo by itself does not warrant urgent CT or MRI in all patients, particularly patients in whom a clear picture of peripheral vertigo emerges. But as mentioned earlier, many studies strongly support the use of imaging in patients of advanced age or at risk for cerebrovascular disease.7,9,16 CT, although often useful for identifying hemorrhage, is insensitive for acute stroke presentations, especially for infarction within the posterior fossa. MRI with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is considered a much more sensitive modality and should be performed quickly in patients with changing neurologic signs and symptoms, suggesting impending posterior circulation occlusion.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for other peripheral, central, and systemic causes of vertigo is large (see Box 19-1). More detailed information is given on selected causes in Table 19-3, including the most common peripheral causes of true vertigo: BPPV, vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and Ménière’s disease.

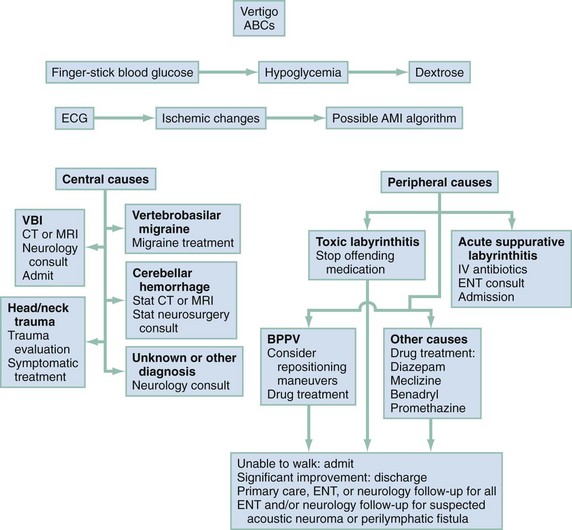

Management

Management is based on an accurate diagnosis that distinguishes the serious central causes of vertigo from the less serious, albeit more debilitating, peripheral causes (Fig. 19-3). Any suggestion of cerebellar hemorrhage warrants immediate imaging with CT or MRI and neurosurgery consultations. VBI should be considered in any patient of advanced age or at high risk of cerebrovascular disease with isolated, new-onset vertigo without an obvious cause.17,18 Because of the possibility of progression of new-onset VBI in the first 24 to 72 hours, hospital or observation unit admission and consideration of early MRA are reasonable, even in a stable patient. Changing or rapidly progressive symptoms suggest impending posterior circulation occlusion. If CT or MRI excludes hemorrhage as the source of the patient’s symptoms, an immediate neurologic consultation, emergency angiography, and possible anticoagulation are indicated.

Acute bacterial labyrinthitis (see Table 19-3) requires hospital admission, intravenous antibiotics, and, occasionally, surgical drainage and débridement. In cases of toxic labyrinthitis, the offending medication is discontinued immediately.

Vestibular neuritis is often thought of as similar to Bell’s palsy. A large multicenter randomized clinical trial19 showed that corticosteroids were helpful in the treatment of vestibular neuritis but antivirals, such as acyclovir, were not. In this study a 22-day taper of methylprednisolone was used beginning with a dose of 100 mg each morning.

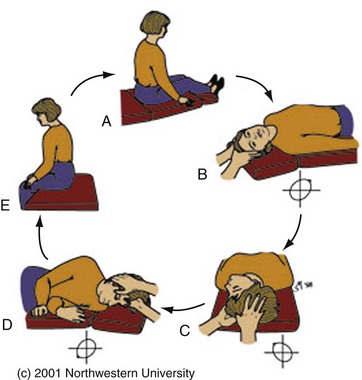

Canalith repositioning procedures, such as the Epley maneuver, are extremely effective in treating BPPV.20,21 The Epley maneuver involves sequential rotations of the head, holding each position for approximately 30 seconds, as demonstrated in Figure 19-4. The “barbecue roll”22 is a simple maneuver that can be used to treat the horizontal canal variant of BPPV (diagnosed by the roll test). The patient lies flat on the gurney with the head turned 90 degrees to the involved side. The head is then rotated in 45-degree intervals away from the involved side (each turn is held approximately 30 seconds or until nystagmus and vertigo resolve). Eventually the patient needs to turn over into the prone position. The maneuver is completed once the head has returned to the original starting position.

Figure 19-4 The Epley maneuver for benign paroxysmal peripheral vertigo, also known as the particle repositioning or canalith repositioning procedure. (Image used with permission of Timothy C. Hain, Professor of Neurology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/bppv/bppv.html.)

Two relatively recent practice guidelines were published that included information on the use of medications to treat BPPV. One found no evidence to support a recommendation of any medication in the routine treatment of BPPV.23 The other concluded that clinicians should not routinely treat BPPV with vestibular suppressant medications. However, both guidelines were from specialty societies whose patients often have chronic and likely milder forms of BPPV than patients who develop acute BPPV and come to the ED. For ED patients who either fail canalith repositioning maneuvers or are actively vomiting and/or too symptomatic to undergo repositioning maneuvers, it is reasonable to administer vestibular suppressants. The most commonly used are the antiemetic medications, which not only suppress nausea and vomiting but also decrease the sensation of vertigo. Although promethazine (Phenergan) is likely the most effective parenteral vestibular suppressant, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently gave intravenous use of promethazine a black box warning, and it is now recommended to be administered only in intramuscular or oral forms. Intravenous ondansetron is an effective alternative parenteral vestibular suppressant.24 Intravenous metoclopramide is not thought to be helpful with acute vertigo, and there is controversy as to whether intravenous prochlorperazine is effective. Patients with intractable vertigo and vomiting that are unresponsive to antiemetics can be given an intravenous benzodiazepine, such as intravenous diazepam. However, it is generally recommended not to discharge patients with oral benzodiazepines because their use can interfere with the process of vestibular habituation, in which the vestibular system learns to adapt to the mismatch of information it is receiving.

References

1. Burt, CW, Schappert, SM. Ambulatory care visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments: United States, 1999-2000. Vital Health Stat. 2004;157:1–70.

2. Kerber, KA, Meurer, WJ, West, BT, Fendrick, AM. Dizziness presentations in U.S. emergency departments, 1995-2004. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:744–750.

3. Lawson, J, Fitzgerald, J, Birchall, J, Aldren, CP, Kenny, RA. Diagnosis of geriatric patients with severe dizziness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:12–17.

4. Drachman, DA, Hart, CW. An approach to the dizzy patient. Neurology. 1972;22:323–334.

5. Sloane, PD, Coeytaux, RR, Beck, RS, Dallara, J. Dizziness: State of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:823–832.

6. Newman-Toker, DE, et al. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: A cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1329–1340.

7. Kerber, KA, Brown, DL, Lisabeth, LD, Smith, MA, Morgenstern, LB. Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department: A population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37:2484–2487.

8. Young, YH, Chen, CH. Acute vertigo following cervical manipulation. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:659–662.

9. Lee, H, et al. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo: Frequency and vascular topographical patterns. Neurology. 2006;67:1178–1183.

10. Son, EJ, Bang, JH, Kang, JG. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery infarction presenting with sudden hearing loss and vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:556–558.

11. Kim, AS, Fullerton, HJ, Johnston, SC. Risk of vascular events in emergency department patients discharged home with diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:34–41.

12. Halker, RB, Barrs, DM, Wellik, KE, Wingerchuk, DM, Demaerschalk, BM. Establishing a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo through the Dix-Hallpike and side-lying maneuvers: A critically appraised topic. Neurologist. 2008;14:201–204.

13. Weber, KP, et al. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss: Vestibulo-ocular reflex and catch-up saccades. Neurology. 2008;70:454–463.

14. Herr, RD, Zun, L, Mathews, JJ. A directed approach to the dizzy patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:664–672.

15. Newman-Toker, DE, et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to U.S. emergency departments: Cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:765–775.

16. Gizzi, M, Riley, E, Molinari, S. The diagnostic value of imaging the patient with dizziness. A Bayesian approach. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:1299–1304.

17. Norrving, B, Magnusson, M, Holtas, S. Isolated acute vertigo in the elderly; vestibular or vascular disease? Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91:43–48.

18. Rathore, SS, Hinn, AR, Cooper, LS, Tyroler, HA, Rosamond, WD. Characterization of incident stroke signs and symptoms: Findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2002;33:2718–2721.

19. Strupp, M, et al. Methylprednisolone, valacyclovir, or the combination for vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:354–361.

20. Chang, AK, Schoeman, G, Hill, M. A randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of the Epley maneuver in the treatment of acute benign positional vertigo. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:918–924.

21. Hilton, M, Pinder, D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2004.

22. Escher, A, Ruffieux, C, Maire, R. Efficacy of the barbecue manoeuvre in benign paroxysmal vertigo of the horizontal canal. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:1239–1241.

23. Fife, TD, et al. Practice parameter: Therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:2067–2074.

24. Bhattacharyya, N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:S47–S81.