CHAPTER 23 Diverticula of the Pharynx, Esophagus, Stomach, and Small Intestine

ZENKER’S DIVERTICULUM

Cause and Pathogenesis

Zenker’s diverticula are acquired. They develop when abnormally high pressures occurring during swallowing lead to protrusion of mucosa through an area of anatomic weakness in the pharynx known as Killian’s triangle. High pressures are generated when the opening of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) is impaired. In patients with Zenker’s diverticula, several pathophysiologic changes have been documented in the cricopharyngeus. These changes lead to a reduction in compliance and to decreased opening of the UES.1 Killian’s triangle is located where the transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeal sphincter intersect with the oblique fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. The size of this area of weakness varies among individuals. Relatively large defects may predispose to the development of Zenker’s diverticula.2

Diverticula similar in appearance to Zenker’s diverticula have been reported as a complication of anterior cervical spine surgery.3,4

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The prevalence of Zenker’s diverticula has been estimated to be between 0.1% and 0.01%. Patients generally present in the seventh or eighth decade of life. Twice as many men as women develop Zenker’s diverticula.1,5 Common presenting symptoms are listed in Table 23-1. Patients with small diverticula may be asymptomatic.

Table 23-1 Presenting Symptoms in Patients with a Zenker’s Diverticulum

Squamous cell cancer may develop in Zenker’s diverticula. The incidence has been estimated to be from 0.4% to 1.5%.1,6,7 If myotomy without diverticulectomy is planned, it is prudent to inspect the lining of the diverticulum carefully for any evidence of cancer.

Bleeding may occur from ulcerated Zenker’s diverticula. Aspiration of retained food contents may complicate induction of anesthesia.8 Medications may become lodged in Zenker’s diverticula. Corrosive medications may cause ulceration. Unpredictable absorption of tablets or capsules may also lead to clinical problems.9 Accumulation of radioactive iodine tracer in a Zenker’s diverticulum has been reported to lead to an erroneous diagnosis of metastatic thyroid cancer.10 Videocapsules may also become lodged in Zenker’s diverticula and should be delivered into the stomach with a fiberoptic endoscope when such studies are required.11,12

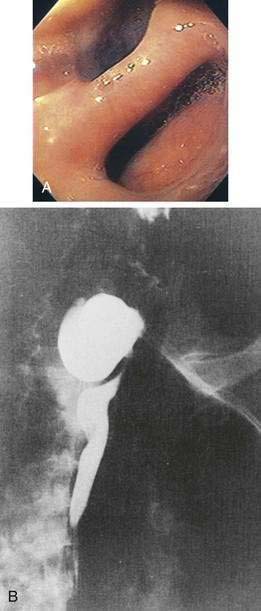

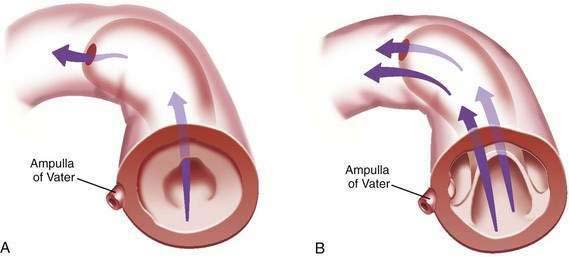

Intubation of the trachea or the esophagus may be complicated by the presence of a Zenker’s diverticulum. A large diverticulum displaces the lumen of the esophagus. The tip of the intubation instrument is directed preferentially into the diverticulum. At endoscopy, it may be difficult to distinguish the lumen of the diverticulum from the true lumen of the esophagus (Fig. 23-1A). Endotracheal intubation, placement of a nasogastric tube, and intubation of the esophagus for upper endoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or transesophageal echocardiography may be difficult. Perforation can occur. Intubation in patients with Zenker’s diverticula should be done under direct vision. When a large Zenker’s diverticulum causes marked anatomic distortion or when intubation with a side-viewing endoscope is required, direct intubation is not prudent. In such cases, a forward-viewing endoscope can be used to pass a soft-tipped guidewire into the esophageal lumen. The guidewire is then back-loaded into the endoscope and the endoscope is advanced into the esophagus over the guidewire. An alternative technique consists of passing a forward-viewing endoscope loaded with an overtube. Once the endoscope has been passed into the esophagus, the overtube is advanced, the forward-viewing endoscope is withdrawn, and the side-viewing or ultrasound endoscope is passed through the overtube.13

Zenker’s diverticulum can be suspected from a careful history (see Table 23-1). Barium swallow is the most useful diagnostic study. The radiologist should be alerted in advance, so that proper views are taken (see Fig. 23-1B). Small diverticula may be seen only transiently. Barium swallow in the lateral view using video fluoroscopy is helpful for detecting small diverticula. The opening of a large Zenker’s diverticulum often becomes aligned with the axis of the esophagus. Oral contrast will preferentially fill the diverticulum and will empty slowly. Large diverticula are therefore often obvious, even on delayed images. During endoscopy, Zenker’s diverticulum should be suspected if, on entering the pharynx, the upper esophageal sphincter cannot be located. In such cases, the endoscopy should be stopped and the patient should be sent for a barium study.

Treatment and Prognosis

Patients with small asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic diverticula can be followed, because progressive enlargement is uncommon.2 Patients with large and symptomatic Zenker’s diverticula should be offered treatment.

Zenker’s diverticula may be treated by open surgical procedures or by transoral endoscopic techniques with rigid or flexible fiberoptic instruments. Open surgery for Zenker’s diverticula can be performed as an outpatient procedure.14 An open surgical approach is the safest alternative for patients with large (>5 cm) diverticula that extend into the thorax.15 Damage to mediastinal structures is best avoided by optimal exposure. Large diverticula can be resected, inverted, or suspended (diverticulopexy). Resection of small diverticula is not required. UES myotomy should always be part of the procedure. If diverticula are resected without myotomy, there is an increased risk of postoperative leaks and an increased frequency of recurrence.16,17 Complications of open surgery include leaks with mediastinitis, esophagocutaneous fistula, and vocal cord paralysis from recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

Endoscopic treatment has become the predominant technique for the management of Zenker’s diverticula since the introduction of stapling for myotomy in 1993. Compared with open surgical approaches, endoscopic approaches are associated with lower complication rates, shorter anesthesia times, and shorter hospital stays.7

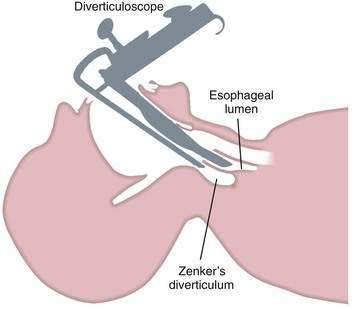

Endoscopic techniques are suitable for patients with medium-sized diverticula (2 to 5 cm). Specially designed rigid diverticuloscopes (e.g., Weerda, van Overbeek) and conventional flexible fiberoptic endoscopes have been used. The diverticuloscope is used to provide optimal visualization of the lumen of the esophagus and diverticulum and the septum between them (Fig. 23-2). This septum is comprised of the posterior wall of the esophagus and the anterior wall of the diverticulum, and includes the UES. The muscular layers of this septum are incised, resulting in ablation of the UES and restoration of a single lumen. The incision can be performed by a number of techniques. With a rigid diverticuloscope, CO2 laser and surgical staplers have been used. Stapling has become the predominant technique since it was reported to be safer and more effective than CO2 laser.7,18 With CO2 laser, fusion of the cut edges of the incision is relied on to prevent leaks. With endoscopic stapler-assisted myotomy, a double row of staples is placed along the cut edges, reducing the risk of perforation and bleeding. Stapling may not be technically feasible if the diverticulum is short (<3 cm), because not enough of the stapler will fit into the diverticulum. Modifications of the stapler and other techniques may improve results in short diverticula.19 Conversion from an endoscopic to an open approach may be necessary in about 10% of patients. Overall, 90% of patients have long-term satisfactory results after endoscopic stapling.17 Complications of endoscopic procedures include bleeding, perforation, and leaks, but these are uncommon if a stapler-assisted technique is used.

Flexible fiberoptic endoscopic techniques also have a role in the treatment of Zenker’s diverticula. Rigid diverticuloscopes cannot be used in patients who have limited neck extension or limited ability to open their mouth.15 Flexible fiberoptic techniques do not require general anesthesia. To improve exposure and stabilize the diverticulum, a transparent cap may be attached to the tip of the endoscope.20–22 Another device developed for this purpose is a soft diverticuloscope used as an overtube.23,24 A variety of techniques are used to perform the endoscopic myotomy, including needle knife, argon plasma coagulation, and monopolar forceps. Several sessions may be required to achieve an adequate myotomy. Complications of fiberoptic flexible techniques include cervical and mediastinal air dissection, which are common, as well as perforation and mediastinitis. Persistent or recurrent symptoms have been reported in 10% to 15% of cases.

DIVERTICULA OF THE ESOPHAGEAL BODY

Cause and Pathogenesis

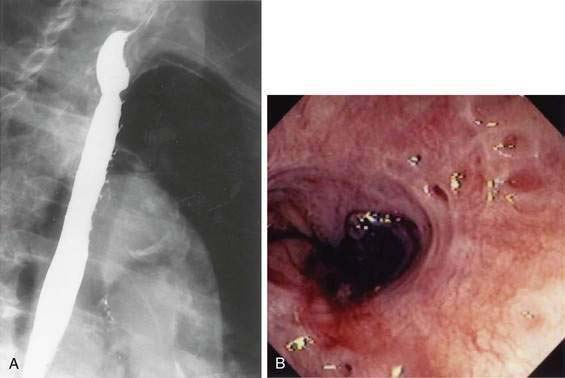

Diverticula of the esophageal body are most commonly located in the middle or lower third of the esophagus (Fig. 23-3). Diverticula located near the diaphragmatic hiatus are called epiphrenic diverticula (Fig. 23-4). Congenital bronchopulmonary-foregut malformations can communicate with the esophagus and present as esophageal diverticula.25 Traction diverticula are often related to mediastinal inflammation associated with tuberculosis and histoplasmosis. Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes from lung malignancies can also lead to traction diverticula. Epiphrenic diverticula are acquired. About 80% are associated with motility disorders, such as achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter, and nonspecific motility disorders.26–28 Epiphrenic diverticula have been reported as a complication of obesity surgery.29

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Congenital and traction diverticula are usually asymptomatic. Bronchopulmonary fistulae can develop, leading to cough, pneumonia, and recurrent bronchopulmonary infections.30 Midbody and distal esophageal diverticula are also usually asymptomatic. If symptoms are not present at diagnosis, they rarely occur during follow-up. When symptoms occur, the most common are dysphagia, food regurgitation, reflux, weight loss, and chest discomfort.31 Dysphagia may be caused by an underlying motility disorder or by extrinsic compression of the esophagus by a large diverticulum, with preferential filling.32,33

An epiphrenic diverticulum may be mistaken for a diaphragmatic hernia or duplication cyst on chest radiography. Diagnosis is best made by barium swallow, which serves to visualize the diverticulum and localizes it more precisely than endoscopy (see Fig. 23-4).

Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported in epiphrenic diverticula.34 As with Zenker’s diverticula, accumulation of radioactive iodine tracer in esophageal diverticula has been mistaken for metastatic thyroid cancer.35

Treatment and Prognosis

Asymptomatic diverticula of the esophagus need no treatment. Only those patients with symptoms clearly related to their diverticula should be treated. Preoperative endoscopy and manometry are advisable. It can be difficult to pass a manometry catheter beyond the diverticulum and into the stomach, but documentation of achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm is helpful for guiding treatment.36 Large diverticula may be inverted or resected. Given the high prevalence of associated motility disorders, esophageal myotomy is performed in most if not all cases.27,28,37 Small diverticula can be treated by myotomy without resection. To prevent gastroesophageal reflux, a nonobstructing fundoplication is usually done.

Surgery for esophageal diverticula may be done by open, laparoscopic, or laparoscopic combined with thoracoscopic techniques.27,28,37,38 Epiphrenic diverticula are often amenable to a laparoscopic approach, which has the advantages of a short hospital stay and a quick return to normal activities.

ESOPHAGEAL INTRAMURAL PSEUDODIVERTICULA

Only about 200 cases have been reported, but EIP are more common than the small number of published case reports would imply. EIP have been demonstrated in about 1% of barium swallow studies.39 In autopsy studies, the incidence has been reported to be as high as 55%.40,41

Cause and Pathogenesis

EIP are abnormally dilated ducts of submucosal glands. They are thought to be acquired, and are often associated with conditions that cause chronic esophageal inflammation. The ducts may become dilated because of periductal inflammation or fibrosis.40,42 Gastroesophageal reflux, chronic candidiasis, previous caustic ingestion, esophageal cancer, and a single case of eosinophilic esophagitis have all been associated with EIP.39,43–45 Esophageal strictures are also commonly associated with EIP.41,46 Marked thickening of the esophageal wall has been noted in some cases by CT or endoscopic ultrasound.47

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Patients are found to have EIP most commonly in their sixth or seventh decades. The condition is slightly more common in men than in women.41 EIP are discovered most commonly on a barium swallow done for dysphagia or heartburn (Fig. 23-5A). EIP may also be an incidental finding in patients without related symptoms. EIP are usually segmental in distribution, but may be diffuse. Stricture is noted in most cases.41 Tracking or communication between adjacent pseudodiverticula is not uncommon if it is looked for carefully.48 The differential diagnosis on barium swallow examination includes esophageal ulceration. Cancer must be excluded by upper endoscopy if a stricture is present. Although the endoscopic appearance of EIP is characteristic (see Fig. 23-5B), the openings of EIP are small and are often missed. EIP located within an area of stricture are particularly difficult to see at endoscopy. Symptoms, when present, are generally related to the associated condition, such as stricture, cancer, acid reflux, or candidiasis, rather than to the EIP. There have been case reports of perforation of EIP leading to mediastinitis.49

GASTRIC DIVERTICULA

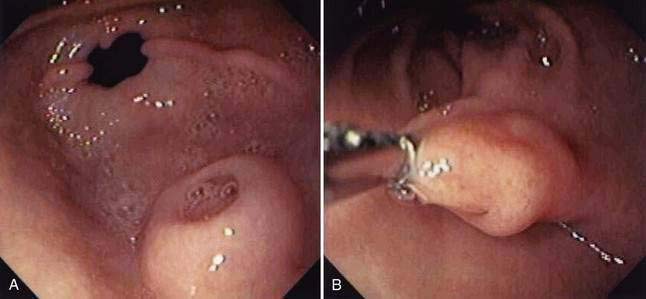

Gastric diverticula are found in less than 1% of upper gastrointestinal x-rays or autopsies.51 Juxtacardiac diverticula make up 75% of all gastric diverticula. These are most often located near the gastroesophageal junction, on the posterior aspect of the lesser curvature.52 They are most commonly found in middle-aged patients, although cases have been reported in children and adolescents.53–55 They range in size from 1 to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 23-6). Intramural or partial gastric diverticula are formed by the projection of the mucosa of the stomach through the muscularis. These diverticula are found most commonly on the greater curvature (Fig. 23-7).56,57 Deformities caused by peptic ulcers or other inflammatory processes can resemble prepyloric diverticula on barium studies or at endoscopy. Gastric diverticula have been reported as complication of obesity surgery.58,59

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Juxtacardiac diverticula are almost always asymptomatic. Rarely, patients may complain of pain or dyspepsia attributable to a diverticulum. Reproduction of pain by probing the diverticulum with a biopsy forceps during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has been reported.60

During endoscopy, juxtacardiac diverticula are best seen on a retroflexed view. Juxtacardiac diverticula may be missed on barium study unless lateral views are taken. On CT scans, they may appear as air- or contrast-filled suprarenal masses and can be mistaken for a necrotic adrenal mass.61,62

Treatment and Prognosis

Intramural diverticula require no intervention. Juxtacardiac diverticula almost never need treatment. A clear association with a specific symptom complex should be firmly established before considering resection. Complications such as ulceration, bleeding, and cancer are very rare. If bleeding occurs, treatment may be challenging. The use of hemoclips has been reported.63 Bleeding that cannot be controlled with endoscopic techniques may require referral for surgery.

Perforation or cancer may be treated by diverticulectomy or partial gastrectomy, respectively. If a patient with a juxtacardiac diverticulum requires referral for surgery, it may be prudent to mark the diverticulum with India ink, because localization by the surgeon can be difficult. Laparoscopic diverticulectomy has been reported.54

DUODENAL DIVERTICULA

Duodenal diverticula can be extraluminal or intraluminal.

EXTRALUMINAL DIVERTICULA

Cause and Pathogenesis

Extraluminal duodenal diverticula are noted in about 5% of upper gastrointestinal x-rays, and in about 25% of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) studies or autopsies.64,65 They are thought to be acquired. They arise in an area of the duodenal wall where a vessel penetrates the muscularis or where the dorsal and ventral pancreas fuse in embryologic development. Approximately 75% are located within 2 cm of the ampulla and are termed juxtapapillary diverticula (JPD).

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Duodenal diverticula are typically diagnosed on upper gastrointestinal x-rays (Fig. 23-8). They are easily missed on endoscopy unless a side-viewing endoscope is used. The sensitivity of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for duodenal diverticula is low.66–69 If a diverticulum is suspected on CT or MRI, the diagnosis can be clarified by having the patient drink water and repeating the scan. The presence of an air-fluid level in the structure will clarify the diagnosis. A duodenal diverticulum may be mistaken for a pancreatic pseudocyst, peripancreatic fluid collection, cystic pancreatic tumor, hypermetabolic mass, or distal common bile duct stone on ultrasound, CT, MRI, or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT.70–74

Although extraluminal duodenal diverticula are relatively common, only a few are associated with clinical problems. Problems associated with extraluminal duodenal diverticula include perforation or diverticulitis, bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and common bile duct stones. Duodenal diverticulitis may present as a free or contained perforation. Patients present with pain in the upper abdomen, often radiating to the back, and may have signs and symptoms of sepsis. An abdominal CT scan may reveal thickening of the duodenum, retroperitoneal air, phlegmon, or abscess. The findings are usually nonspecific and the diagnosis is often not made until exploratory laparotomy.69,75

Bleeding has been reported from Dieulafoy-like lesions or ulcers within diverticula.76–78 Bleeding from duodenal diverticula may be very difficult to diagnose, requiring examination with a side-viewing endoscope or angiography. In some patients, the site of bleeding is discovered only at laparotomy and duodenotomy.

Patients with multiple duodenal diverticula may develop bacterial overgrowth and malabsorption (see Chapter 102).79 Juxtapapillary diverticula have been associated with common bile duct stones, cholangitis, and recurrent pancreatitis.80–85 The presence of a juxtapapillary diverticulum has been shown to lead to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.86 Delayed emptying of the common bile duct may occur, even after sphincterotomy. Stasis within diverticula can result in local bacterial overgrowth, favoring deconjugation of bilirubin and thus increasing the risk of primary common bile duct stones.81

JPD do not appreciably increase the difficulty of cannulation or the risk of complications at ERCP unless the papilla is not visible within the diverticulum.83,87 Several techniques have been described to overcome difficulties associated with an ampulla situated deep within a diverticulum.88,89

Treatment and Prognosis

Extraluminal duodenal diverticula rarely require therapeutic intervention. Resection of duodenal diverticula should never be done for vague abdominal complaints. Bleeding, diverticulitis, and perforation are the most common problems associated with duodenal diverticula. Endoscopic control of bleeding from diverticula has been accomplished using various techniques, including bipolar cautery, epinephrine injection, and hemoclips.76–7890 If the diagnosis is not made preoperatively, surgical control of bleeding can be accomplished through a duodenotomy. Damage to the pancreatic and biliary ducts may occur during surgery in patients with periampullary diverticula.

Most patients with perforation or diverticulitis undergo laparotomy for diagnosis. The usual surgical treatment is drainage and resection of the involved diverticulum, if feasible. If the diagnosis is made preoperatively, successful conservative therapy by percutaneous drainage and antibiotics is possible.75,91

INTRALUMINAL DIVERTICULA

Intraluminal duodenal diverticula (windsock diverticula) are single saccular structures that originate in the second portion of the duodenum. They are connected to the entire circumference or only to part of the wall of the duodenum and may project as far distally as the fourth part of the duodenum. There is often a second opening located eccentrically in the sac (Fig. 23-9). Both sides of the diverticulum are lined by duodenal mucosa. Fewer than 100 cases have been reported.

Cause and Pathogenesis

During early fetal development, the duodenal lumen is occluded by proliferating epithelial cells and later recanalized (see Chapter 47). Abnormal recanalization may lead to a duodenal diaphragm or web. An incomplete or fenestrated diaphragm may not produce obstructive symptoms in childhood. Over time, peristaltic stretching may transform the diaphragm into an intraluminal diverticulum.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Intraluminal diverticula may become symptomatic at any age. The most common symptoms are those of incomplete duodenal obstruction.92,93 Obstruction may be precipitated by retention of vegetable material or foreign bodies within the diverticulum. In one report, a 41-year-old man was found to have two marbles, swallowed during childhood, retained in an intraluminal diverticulum.94 Pancreatitis and bleeding have also been reported.95,96 The typical radiographic appearance is that of a barium-filled globular structure of variable length, originating in the second portion of the duodenum, with its fundus extending into the third portion, and outlined by a thin, radiolucent line. The CT appearance has been reported as a ring-like soft tissue density in the lumen of the second portion of the duodenum, outlined with oral contrast and containing oral contrast and a small amount of air (halo sign).97

At endoscopy, an intraluminal diverticulum is a sac-like structure with an eccentric aperture or a large, soft, polypoid mass if the diverticulum is inverted orad.96,98 Endoscopic diagnosis may be difficult. A long sac may be mistaken for the duodenal lumen, whereas an inverted diverticulum may be mistaken for a large polyp. Gastric retention or dilation of the duodenal bulb may result from chronic partial obstruction caused by the diverticulum.

JEJUNAL DIVERTICULA

Diverticula of the small bowel (apart from duodenal and Meckel’s diverticula) are most commonly found in the proximal jejunum. About 80% of jejunoileal diverticula arise in the jejunum, 15% in the ileum, and 5% in both; small bowel diverticula have been found in about 0.5% to 5% of small bowel x-rays and autopsies.99,100 They are commonly multiple and can vary from a few millimeters to 10 cm in length. They are usually located on the mesenteric border of the small bowel. Small bowel diverticula generally lack a true muscular wall and are considered to be acquired.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The cause of jejunoileal diverticula is largely unknown. Many patients have an underlying intestinal motility disorder. Periodic elevated intraluminal pressures can lead to herniation through areas of weakness at the mesenteric border where blood vessels penetrate the muscularis. Visceral neuropathies and myopathies, including progressive systemic sclerosis, can lead to chronic atrophy and fibrosis of the intestinal wall, with resultant herniation and diverticula formation.101

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Jejunal diverticula are best diagnosed by upper gastrointestinal radiography with small bowel follow-through. They may also be found by CT.102 Jejunal diverticula most commonly occur on the mesenteric border of the bowel, in contrast to Meckel’s diverticula, which occur on the antimesenteric border.

Jejunal diverticula have been discovered by double-balloon enteroscopy, and diverticular bleeding has been treated with this technique.103,104 On the other hand, if a patient is known or discovered to have small bowel diverticula, it may be prudent to avoid enteroscopy because of the risk of perforation.105

Many cases of jejunoileal diverticulosis are asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms for which patients may not seek medical attention. About 40% of cases are discovered incidentally.100 In 1881, Sir William Osler wrote about a patient with jejunal diverticula who, for years, “had suffered much from loud rumbling noises in his belly, particularly after each meal. So loud were they that it was his habit, shortly after eating, to go out and take a walk to keep away from people, as the noises could be heard at some distance.”

Various symptoms and clinical problems may occur with jejunal diverticula.106 The most common clinical features are recurrent abdominal pain, early satiety, and bloating. Loud borborygmi and intermittent diarrhea may occur. These symptoms are likely caused by an underlying motility disorder. Malabsorption may result from associated bacterial overgrowth (see Chapters 101 and 102).100,107,108 Patients with jejunal diverticulosis and severe dysmotility develop a syndrome of intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Patients with this clinical picture may periodically have free intraperitoneal air (pneumoperitoneum) without overt perforation. If such patients are otherwise well, they should be carefully observed. Laparotomy is often not necessary.

Bleeding from small bowel diverticula may be difficult to localize.109,110 If a source of bleeding is discovered in the small bowel at angiography, it may be useful to leave a small catheter within the feeding vessel as the patient is taken to the operating room. When the patient is explored, a small amount of dye can be injected through the catheter, staining the involved bowel. This may help the surgeon localize an otherwise obscure lesion. Capsule endoscopy has been reported to discover small bowel diverticula.111,112

Diverticulitis may result in free perforation or an abscess contained within the mesentery.113 Preoperative diagnosis is difficult. The finding of an inflammatory mass in the mesentery should raise the possibility of small bowel diverticula.114 Because jejunal diverticula usually project into the mesentery, they can be difficult to detect, even at surgery.

Large enteroliths can form in jejunal diverticula and lead to erosion, with bleeding, diverticulitis, perforation, or intestinal obstruction.115–117

If a small bowel volvulus is found in an adult, small bowel diverticulosis should be considered, because it appears that there is an association between the two conditions.118

Treatment and Prognosis

There is no specific treatment for symptoms related to intestinal dysmotility. The use of oral antibiotics to treat associated bacterial overgrowth may lead to improvement in bloating and diarrhea, as well as malabsorption (see Chapters 101 and 102).

In patients with bleeding, perforation, or diverticulitis, limited surgical resection of the section of bowel with the offending diverticulum should be the goal, but this may be difficult to localize with precision.119,120 In patients with symptoms of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, surgery should generally be avoided, although carefully selected patients may benefit.121 If a long segment of bowel is resected in an attempt to remove all the diverticula, the patient may not only be left with a short bowel syndrome (see Chapter 103), but underlying dysmotility may also involve the remaining intestine, compromising its function and leading to severe disability.

Aly A, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG. Evolution of surgical treatment for pharyngeal pouch. Br J Surg. 2004;91:657-64. (Ref 17.)

Ames JT, Federle MP, Pealer KM. Perforated duodenal diverticulum: Clinical and imaging findings in eight patients. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:135-9. (Ref 69.)

Christiaens P, De RW, Van OA, et al. Treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum through a flexible endoscope with a transparent oblique-end hood attached to the tip and a monopolar forceps. Endoscopy. 2007;39:137-40. (Ref 21.)

Costamagna G, Iacopini F, Tringali A, et al. Flexible endoscopic Zenker’s diverticulotomy: Cap-assisted technique vs. diverticuloscope-assisted technique. Endoscopy. 2007;39:146-52. (Ref 24.)

Ferreira LE, Simmons DT, Baron TH. Zenker’s diverticula: Pathophysiology, clinical features, and flexible endoscopic management. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:1-8. (Ref 5.)

Fintelmann F, Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Jejunal diverticulosis: Findings on CT in 28 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1286-90. (Ref 102.)

Liu CY, Chang WH, Lin SC, et al. Analysis of clinical manifestations of symptomatic acquired jejunoileal diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5557-60. (Ref 106.)

Macari M, Faust M, Liang H, Pachter HL. CT of jejunal diverticulitis: Imaging findings, differential diagnosis, and clinical management. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:73-7. (Ref 114.)

Panteris V, Vezakis A, Filippou G, et al. Influence of juxtapapillary diverticula on the success or difficulty of cannulation and complication rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:903-10. (Ref 87.)

Rabenstein T, May A, Michel J, et al. Argon plasma coagulation for flexible endoscopic Zenker’s diverticulotomy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:141-5. (Ref 22.)

Seaman DL, de la Mora LJ, Gostout CJ, et al. A new device to simplify flexible endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:112-15. (Ref 23.)

Sen P, Kumar G, Bhattacharyya AK. Pharyngeal pouch: Associations and complications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:463-8. (Ref 1.)

Tedesco P, Fisichella PM, Way LW, Patti MG. Cause and treatment of epiphrenic diverticula. Am J Surg. 2005;190:891-4. (Ref 27.)

Varghese TKJr, Marshall B, Chang AC, et al. Surgical treatment of epiphrenic diverticula: A 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1801-9. (Ref 37.)

Vogelsang A, Preiss C, Neuhaus H, Schumacher B. Endotherapy of Zenker’s diverticulum using the needle-knife technique: Long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2007;39:131-6. (Ref 20.)

1. Sen P, Kumar G, Bhattacharyya AK. Pharyngeal pouch: Associations and complications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:463-8.

2. van Overbeek JJ. Pathogenesis and methods of treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:583-93.

3. Ba AM, LoTempio MM, Wang MB. Pharyngeal diverticulum as a sequela of anterior cervical fusion. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:295-7.

4. Summers LE, Gump WC, Tayag EC, Richardson DE. Zenker diverticulum: A rare complication after anterior cervical fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:172-5.

5. Ferreira LE, Simmons DT, Baron TH. Zenker’s diverticula: Pathophysiology, clinical features, and flexible endoscopic management. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:1-8.

6. Acharya A, Jennings S, Douglas S, et al. Carcinoma arising in a pharyngeal pouch previously treated by endoscopic stapling. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1043-5.

7. Siddiq MA, Sood S. Current management in pharyngeal pouch surgery by UK otorhinolaryngologists. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:247-52.

8. Thiagarajah S, Lear E, Keh M. Anesthetic implications of Zenker’s diverticulum. Anesth Analg. 1990;70:109-11.

9. Langdon DE. Medication decisions in giant Zenker’s and esophageal diverticula. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:943-4.

10. Rashid K, Johns W, Chasse K, et al. Esophageal diverticulum presenting as metastatic thyroid mass on iodine-131 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:405-8.

11. Simmons DT, Baron TH. Endoscopic retrieval of a capsule endoscope from a Zenker’s diverticulum. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:338-9.

12. Aabakken L, Blomhoff JP, Jermstad T, Lynge AB. Capsule endoscopy in a patient with Zenker’s diverticulum. Endoscopy. 2003;35:799.

13. Ramjohn J, Paulus DA. Use of transesophageal echocardiography in a patient with Zenker’s diverticulum. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:385-6.

14. Gross ND, Cohen JI, Andersen PE. Outpatient endoscopic Zenker diverticulotomy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:208-11.

15. Zaninotto G, Narne S, Costantini M, et al. Tailored approach to Zenker’s diverticula. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:129-33.

16. Veenker E, Cohen JI. Current trends in management of Zenker diverticulum. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:160-5.

17. Aly A, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG. Evolution of surgical treatment for pharyngeal pouch. Br J Surg. 2004;91:657-64.

18. Miller FR, Bartley J, Otto RA. The endoscopic management of Zenker diverticulum: CO2 laser versus endoscopic stapling. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1608-11.

19. Richtsmeier WJ. Myotomy length determinants in endoscopic staple-assisted esophagodiverticulostomy for small Zenker’s diverticula. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:341-6.

20. Vogelsang A, Preiss C, Neuhaus H, Schumacher B. Endotherapy of Zenker’s diverticulum using the needle-knife technique: Long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2007;39:131-6.

21. Christiaens P, De RW, Van OA, Moons V, D’Haens G. Treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum through a flexible endoscope with a transparent oblique-end hood attached to the tip and a monopolar forceps. Endoscopy. 2007;39:137-40.

22. Rabenstein T, May A, Michel J, et al. Argon plasma coagulation for flexible endoscopic Zenker’s diverticulotomy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:141-5.

23. Seaman DL, de la Mora LJ, Gostout CJ, et al. A new device to simplify flexible endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:112-15.

24. Costamagna G, Iacopini F, Tringali A, et al. Flexible endoscopic Zenker’s diverticulotomy: Cap-assisted technique vs. diverticuloscope-assisted technique. Endoscopy. 2007;39:146-52.

25. Yoshida J, Ikeda S, Mizumachi S, et al. Epiphrenic diverticulum composed of airway components attributed to a bronchopulmonary foregut malformation: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:663-5.

26. do Nascimento FA, Lemme EM, Costa MM. Esophageal diverticula: Pathogenesis, clinical aspects, and natural history. Dysphagia. 2006;21:198-205.

27. Tedesco P, Fisichella PM, Way LW, Patti MG. Cause and treatment of epiphrenic diverticula. Am J Surg. 2005;190:891-4.

28. Reznik SI, Rice TW, Murthy SC, et al. Assessment of a pathophysiology-directed treatment for symptomatic epiphrenic diverticulum. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:320-7.

29. Stroh C, Hohmann U, Meyer F, Manger T. Epiphrenic esophageal diverticulum after laparoscopic placement of an adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2006;16:372-4.

30. Lopez A, Rodriguez P, Santana N, Freixinet J. Esophagobronchial fistula caused by traction esophageal diverticulum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:128-30.

31. Michael H, Fisher RS. Treatment of epiphrenic and mid-esophageal diverticula. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:41-52.

32. Niv Y, Fraser G, Krugliak P. Gastroesophageal obstruction from food in an epiphrenic esophageal diverticulum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:314-16.

33. Fasano NC, Levine MS, Rubisen SE, et al. Epiphrenic diverticulum: Clinical and radiographic findings in 27 patients. Dysphagia. 2003;18:9-15.

34. Lai ST, Hsu CP. Carcinoma arising from an epiphrenic diverticulum: A frequently misdiagnosed disease. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;13:110-13.

35. Nguyen BD, Roarke MC. Epiphrenic diverticulum: potential pitfall in thyroid cancer iodine-131 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:631-2.

36. Streitz JMJr, Glick ME, Ellis FHJr. Selective use of myotomy for treatment of epiphrenic diverticula. Manometric and clinical analysis. Arch Surg. 1992;127:585-7.

37. Varghese TKJr, Marshall B, Chang AC, et al. Surgical treatment of epiphrenic diverticula: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1801-9.

38. Fernando HC, Luketich JD, Samphire J, et al. Minimally invasive operation for esophageal diverticula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:2076-80.

39. Levine MS, Moolten DN, Herlinger H, Laufer I. Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis: A reevaluation. Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:1165-70.

40. Medeiros LH, Doos WG, Balogh K. Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis: A report of two cases with analysis of similar, less extensive changes in normal autopsy esophagi. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:928-31.

41. Sabanathan S, Salama FD, Morgan WE. Oesophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. Thorax. 1985;40:849-857.

42. Umlas J, Sakhuja R. The pathology of esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;65:314-20.

43. Kochhar R, Mehta SK, Nagi B, Goenka MK. Corrosive acid-induced esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. A study of 14 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:371-5.

44. Plavsic BM, Chen MYM, Gelfand DW, et al. Intramural pseudodiverticulosis of the esophagus detected on barium esophagrams: Increased prevalence in patients with esophageal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1381-5.

45. Tsai CM, Butler J, Cash BD. Pseudodiverticulosis with eosinophilic esophagitis: First reported case. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1223-4.

46. Koyama S, Watanabe M, Iijima T. Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis (diffuse type). J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:644-8.

47. Mahajan SK, Warshauer DM, Bozymski EM. Esophageal intramural pseudo-diverticulosis: Endoscopic and radiologic correlation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:565-7.

48. Canon CL, Levine MS, Cherukuri R, et al. Intramural tracking: A feature of esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:371-4.

49. Abrams LJ, Levine MS, Laufer I. Esophageal peridiverticulitis: An unusual complication of esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. Eur J Radiol. 1995;19:139-41.

50. Teraishi F, Fujiwara T, Jikuhara A, et al. Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis with esophageal strictures successfully treated with dilation therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1119-21.

51. Palmer ED. Collective review: Gastric diverticula. Int Abs Surg. 1951;92:417-28.

52. Tillander H, Hesselsjo R. Juxtacardial gastric diverticula and their surgery. Acta Chir Scand. 1968;134:255-63.

53. Elliott S, Sandler AD, Meehan JJ, Lawrence JP. Surgical treatment of a gastric diverticulum in an adolescent. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1467-9.

54. Kubiak R, Hamill J. Laparoscopic gastric diverticulectomy in a 13-year-old girl. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:29-31.

55. Lopez ME, Whyte C, Kleinhaus S, et al. Laparoscopic excision of a gastric diverticulum in a child. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:246-8.

56. Treichel J, Gerstenberg E, Palme G, Klemm T. Diagnosis of partial gastric diverticula. Radiology. 1976;119:13-8.

57. Cockrell CH, Cho S-R, Messmer JM, et al. Intramural gastric diverticula: a report of three cases. Br J Radiol. 1984;57:285-8.

58. Goitein D, Papasavas PK, Gagne DJ, et al. Laparoscopic resection of gastric diverticulum presenting after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:528-30.

59. Pretolesi F, Camerini G, Carlini F, et al. Pouch diverticula after vertical-banded gastroplasty. Radiol Med (Torino). 2006;111:890-6.

60. Anaise D, Brand DL, Smith NL, et al. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:28-30.

61. Verbeeck N, De Geeter T. Suprarenal mass caused by a gastric diverticulum. J Belge Radiol. 1994;77:119-20.

62. Chasse E, Buggenhout A, Zalcman M, et al. Gastric diverticulum simulating a left adrenal tumor. Surgery. 2003;133:447-8.

63. Lajoie A, Strum WB. Gastric diverticulum presenting as acute hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:175-6.

64. Lotveit T, Skar V, Osnes M. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula. Endoscopy. 1988;20:175-8.

65. Lobo DN, Balfour TW, Iftikhar SY, Rowlands BJ. Periampullary diverticula and pancreaticobiliary disease. Brit J Surg. 1999;86:588-97.

66. Macari M, Lazarus D, Israel G, Megibow A. Duodenal diverticula mimicking cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: CT and MR imaging findings in seven patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:195-9.

67. Tsitouridis I, Emmanouilidou M, Goutsaridou F, et al. MR cholandiography in the evaluation of patients with duodenal periampullary diverticulum. Eur J Radiol. 2003;47:154-60.

68. Balci NC, Akinci A, Akun E, Klor HU. Juxtapapillary diverticulum. Findings on CT and MRI. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:82-8.

69. Ames JT, Federle MP, Pealer KM. Perforated duodenal diverticulum: Clinical and imaging findings in eight patients. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:135-9.

70. Stone EE, Brant WE, Smith GB. Computed tomography of duodenal diverticula. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:61-3.

71. Levin MF, Bach DB, Vellet AD, et al. Sonolucent peripancreatic masses: Differential diagnosis and related imaging. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1993;44:168-75.

72. Piesman M, Hwang I, Moses FM, Allen TW. Duodenal diverticulum presenting as a hypermetabolic mass on F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:747-8.

73. Mazziotti S, Costa C, Ascenti G, et al. MR cholangiopancreatography diagnosis of juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum simulating a cystic lesion of the pancreas: Usefulness of an oral negative contrast agent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:432-5.

74. Hariri A, Siegelman SS, Hruban RH. Duodenal diverticulum mimicking a cystic pancreatic neoplasm. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:562-4.

75. Verbeek N, Mazy V, Hoebeke Y. Duodenal diverticulitis. CT diagnosis and conservative management. JBR-PTR. 1999;82:99-100.

76. Raju GS, Nath S, Zhao X, et al. Duodenal diverticular hemostasis with hemoclip placement on the bleeding and feeder vessels: A case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:116-17.

77. Gunji N, Miyamoto H. Endoscopic management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding from a duodenal diverticulum. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1940-2.

78. Kachi M, Fujii M, Tateiwa S, et al. Endoscopic injection therapy for the treatment of duodenal diverticulum bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1241-2.

79. Scudmore CH, Harrison RC, White TT. Management of duodenal diverticula. Can J Surg. 1982;25:311-14.

80. Skar V, Lotveit T, Osnes M. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula predispose to common bile duct stones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:202-4.

81. Zoepf T, Zoepf D-S, Arnold JC, et al. The relationship between juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and disorders of the biliopancreatic system: Analysis of 350 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:56-61.

82. Christoforidis E, Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, et al. The role of juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula in biliary stone disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:543-7.

83. Tham TC, Kelly M. Association of periampullary duodenal diverticula with bile duct stones and with technical success of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1050-3.

84. Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Chatzimavroudis G, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for acute relapsing pancreatitis associated with periampullary diverticula: A long-term follow-up. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70:195-8.

85. Tzeng JJ, Lai KH, Peng NJ, et al. Influence of juxtapapillary diverticulum on hepatic clearance in patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:772-6.

86. Miyazaki S, Sakamoto T, Miyata M, et al. Function of the sphincter of Oddi in patients with juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula: Evaluation by intraoperative biliary manometry under a duodenal pressure load. World J Surg. 1995;19:307-12.

87. Panteris V, Vezakis A, Filippou G, et al. Influence of juxtapapillary diverticula on the success or difficulty of cannulation and complication rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:903-10.

88. Toth E, Lindstrom E, Fork FT. An alternative approach to the inaccessible intradiverticular papilla. Endoscopy. 1999;31:554-6.

89. Scotiniotis I, Ginsberg GG. Endoscopic clip-assisted biliary cannulation: Externalization and fixation of the major papilla from within a duodenal diverticulum using the endoscopic clip fixing device. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:431-6.

90. Lee B-I, Kim B-W, Choi H, et al. Hemoclip placement through a forward-viewing endoscope for a Dieulafoy-like lesion in a duodenal diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:813-14.

91. Gore RM, Ghahremani GG, Kirsch MD, et al. Diverticulitis of the duodenum: Clinical and radiological manifestations of seven cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:981-5.

92. Perich Alsina J, Vilana Puig R, Maroto Genover A, et al. Diverticulos intraduodenales. A proposito de seis observaciones. Rev Esp Enf Ap Digest. 1989;75:53-7.

93. Karoll MP, Ghahremani GG, Port RB, Rosenberg JL. Diagnosis and management of intraluminal duodenal diverticulum. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:411-16.

94. Abdel-Hafiz AA, Birkett, Dh, Ahmed MS. Congenital duodenal diverticula: A report of three cases and a review of the literature. Surgery. 1988;104:74-8.

95. Finnie IA, Ghosh P, Garvey C, et al. Intraluminal duodenal diverticulum causing recurrent pancreatitis: Treatment by endoscopic incision. Gut. 1994;35:557-9.

96. De Castro ML, Hermo JA, Pineda JR, et al. Acute bleeding and anemia associated with intraluminal duodenal diverticulum: Case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:976-9.

97. Tu AS, Tran M-HT, Larsen CR. CT-appearance of intraluminal duodenal diverticulum. The “halo” sign. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1998;22:81-3.

98. Adams DB. Management of the intraluminal duodenal diverticulum: Endoscopy or duodenotomy? Am J Surg. 1986;151:524-6.

99. Longo WE, Vernava AM3rd. Clinical implications of jejunoileal diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:381-8.

100. Tsiotos GG, Farnell MB, Ilstrup DM. Nonmeckelian jejunal or ileal diverticulosis: An analysis of 112 cases. Surgery. 1994;116:726-32.

101. Krishnamurthy S, Kelly MM, Rohrmann CA, Schuffler MD. Jejunal diverticulosis. A heterogenous disorder caused by a variety of abnormalities of smooth muscle or myenteric plexus. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:538-47.

102. Fintelmann F, Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Jejunal diverticulosis: Findings on CT in 28 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1286-90.

103. Yen HH, Chen YY, Soon MS. Double-balloon enteroscopic treatment for bleeding jejunal diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:371-2.

104. Kamal A, Gerson LB. Jejunal diverticulosis diagnosed by double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:864.

105. Yen HH, Chen YY. Jejunal diverticulosis: A limiting condition to double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:847-8.

106. Liu CY, Chang WH, Lin SC, et al. Analysis of clinical manifestations of symptomatic acquired jejunoileal diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5557-60.

107. Palder SB, Frey CB. Jejunal diverticulosis. Arch Surg. 1988;123:889-94.

108. Cooke WT, Cox EV, Fone DJ, Meynell MJ, Gaddie R. The clinical and metabolic significance of jejunal diverticula. Gut. 1963;4:115-31.

109. Rodriguez HE, Ziauddin F, Quiros ED, et al. Jejunal diverticulosis and gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:412-14.

110. El-Haddawi F, Civil ID. Acquired jejuno-ileal diverticular disease: A diagnostic and management challenge. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:584-9.

111. Hartmann D, Schilling D, Bolz G, et al. Capsule endoscopy versus push enteroscopy in patients with occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Z Gastroenterol. 2003;41:377-82.

112. Mylonaki M, MacLean D, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopic detection of Meckel’s diverticulum after nondiagnostic surgery. Endoscopy. 2002;34:1018-20.

113. Nightingale S, Nikfarjam M, Iles L, Djeric M. Small bowel diverticular disease complicated by perforation. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:867-9.

114. Macari M, Faust M, Liang H, Pachter HL. CT of jejunal diverticulitis: Imaging findings, differential diagnosis, and clinical management. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:73-7.

115. Hayee B, Khan HN, Al-Mishlab T, McPartin JF. A case of enterolith small bowel obstruction and jejunal diverticulosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:883-4.

116. Steenvoorde P, Schaardenburgh P, Viersma JH. Enterolith ileus as a complication of jejunal diverticulosis. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2003;20:57-60.

117. Crace PP, Grisham A, Kerlakian G. Jejunal diverticular disease with unborn enterolith presenting as a small bowel obstruction: a case report. Am Surg. 2007;73:703-5.

118. Chou CK, Mark CW, Wu RH, Chang JM. Large diverticulum and volvulus of the small bowel in adults. World J Surg. 2005;29:80-2.

119. Geroulakos G. Sugical problems of jejunal diverticulosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69:266-8.

120. Lempinen M, Salmela K, Kemppainen E. Jejunal diverticulosis: A potentially dangerous entity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:905-9.

121. Noel RFJr, Schuffler MD, Helton WS. Small bowel resection for relief of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1142-5.