CHAPTER 11 Distal pancreatic resection

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ The most common indications for performing distal pancreatectomy are benign or malignant neoplasm, complications of pancreatitis, and occasionally trauma.

♦ Although there has been extensive literature on the role of open distal pancreatectomy for malignant disease, there is only a nascent literature on the role of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy.

♦ Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy remains a procedure usually conducted for benign pancreatic disease. This chapter reviews the perioperative care and discusses the operative techniques for laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy.

Step 2. Preoperative consideration

Patient preparation

♦ A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan utilizing a pancreatic protocol is obtained for preoperative assessment of pancreatic disease. This study provides images of the pancreas during arterial and venous phases to allow for a full evaluation of smaller lesions and to help delineate the relationship of the splenic vessels to the lesion.

♦ Patients with radiographic abnormalities of the body and tail of the pancreas usually undergo endoscopic ultrasound with or without FNA (fine needle aspiration) and cystic fluid sampling if indicated.

♦ In patients with a dilated pancreatic duct, an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be useful for evaluating the papilla and ductal anatomy and its relationship to the lesion. Alternatively, Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is also useful as a noninvasive means for elucidating pancreatic pathology and anatomy.

♦ In our institution, a pancreas protocol CT and EUS (Endoscopic Ultrasound) fully assess the majority of patients and obviate the need for additional studies.

♦ If splenectomy is anticipated, then preoperative vaccination against encapsulated bacteria (H. Influenza, Streptococcus, Meningococcus) should be given 7 to 10 days before surgery.

♦ Patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors may require preoperative hospitalization to optimize physiologic status.

♦ Similar to other major abdominal surgeries, preoperative antibiotics and DVT (deep venous thrombosis) prophylaxis are provided per Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) guidelines.

Equipment and instrumentation

♦ For a laparoscopic approach, a 30-degree and 45-degree laparoscope, ultrasonic dissector, 5-mm and 10-mm clip applier, blunt-tipped atraumatic bowel graspers, fine-tipped needle driver, articulating endoscopic stapler, fibrin glue with laparoscopic delivery device, and hand port should be available.

♦ In addition, a laparoscopic ultrasound should be available to help locate and characterize lesions intraoperatively. The ultrasound is often particularly useful for clarifying the spatial relationship of neuroendocrine tumors to the main pancreatic duct. In addition, intraoperative ultrasound may help explain other occult pathology, which may change intraoperative decision-making.

Anesthesia

♦ General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation and complete neuromuscular blockade is generally required for this operation.

♦ After intubation, a nasogastric (NG) tube should be placed to decompress the stomach during the operation and for patient care during the immediate postoperative period.

♦ A Foley catheter should be placed and standard preoperative antibiotics given per surgeon.

Room setup and patient positioning

♦ The patient is positioned in a 30-degree right lateral decubitus position using a beanbag or large gel rolls. This allows for rotation of the patient during mobilization of the pancreas and allows the use of gravity as a retractor during the case. The 30-degree lateral decubitus also provides for rotation into a horizontal position if conversion to an open procedure is required.

Step 3. Operative steps

♦ There are several technical variations that may be utilized based on surgeon preference and characteristics of the operative field.

♦ Pancreatic mobilization can be performed from lateral to medial or from medial to lateral. In general, the lateral-to-medial approach is often easier. However, this does not allow for early control of the splenic artery and vein.

♦ For extended distal pancreatic resections, we often prefer to proceed from medial to lateral, beginning with division of the neck of the pancreas. This facilitates later dissection by allowing early control of the splenic vessels. The medial-to-lateral approach is also useful to aid mobilization of the vessels when splenic preservation is considered. Complete splenic mobilization is not necessary unless the spleen is to be removed.

♦ We will describe laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with en bloc splenectomy via a medial-to-lateral approach and follow this with a discussion of how splenic preservation can be done laparoscopically.

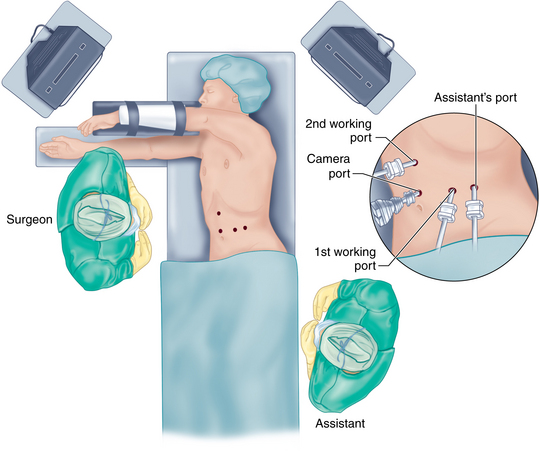

Access and port placement

♦ Pneumoperitoneum is achieved by either the Veress needle technique, with the needle placed through the umbilicus, or the open Hassan technique at the site of the operating laparoscope. The laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection is performed via four trocars.

♦ A critical component of any laparoscopic approach is port placement.

♦ The locations of these trocars may vary slightly depending on the body habitus of the patient. In general, the trocars should be triangulated around the body and tail of the pancreas with a working distance that allows sufficient range of motion.

♦ We have obtained the greatest flexibility by utilizing three 12-mm trocars and one 5-mm trocar.

♦ Figure 11-1 outlines the position of the trocars. In general, a 12-mm trocar is placed in the supraumbilical position to the left of the midline, and exploratory laparoscopy is performed. A 12-mm trocar is placed just 5 cm lateral to the left midclavicular line. This trocar will allow passage of the flexible laparoscopic ultrasound probe and the articulated endoscopic staple device. The assistant’s port is a 5-mm trocar placed in the left midclavicular line approximately 10 cm above the camera port. If necessary this position can be converted into a hand port during the operation. Finally, a fourth 12-mm trocar is placed in the right midclavicular line approximately 5 cm above the camera port. An additional 5-mm subxiphoid trocar can be added, retracting the left lobe of the liver if necessary.

♦ In general, the principles of laparoscopic resection are similar to an open distal pancreatectomy.

Lesser sac exposure

♦ To access the lesser sac, the patient is first placed in a reverse Trendelenburg position to allow gravity to drop the great omentum and the small bowel from the operating field. If a large left lobe of the liver obscures the stomach, a Nathanson or other liver retractor should be placed in the epigastrium and the left lobe retracted.

♦ The assistant retracts the stomach in an anterior and cephalad direction. Using an ultrasonic dissector, the lesser sac is entered by dividing the gastrocolic omentum along the greater curvature of the stomach, with care to avoid injury to the right gastroepiploic vessels. This dissection can usually be started 5 cm proximal to the pylorus on the greater curve of the stomach. Care must be taken to avoid contact with the gastric wall to prevent thermal injury from the ultrasonic dissector.

♦ Alternatively, the lesser sac can be entered through the avascular plane superior to the transverse colon, but this option may leave the greater omentum in the operative field. The mobilization is continued proximally along the greater curvature by dividing all of the short gastric vessels. Congenital adhesions between the posterior wall of the stomach and the pancreas are divided, and the lesser sac is fully visualized.

♦ In patients with chronic pancreatitis or desmoplastic reaction from a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, there may be significant adhesions in this lesser sac space, and careful dissection to mobilize the posterior wall of the stomach will be necessary. To maintain exposure of the pancreas within the lesser sac, the stomach is secured to the anterior abdominal wall using percutaneously inserted T fasteners or laparoscopically placed sutures.

♦ Once the pancreatic body and tail are exposed, laparoscopic ultrasound can assist in locating and determining morphology and respectability of the pancreatic lesion.

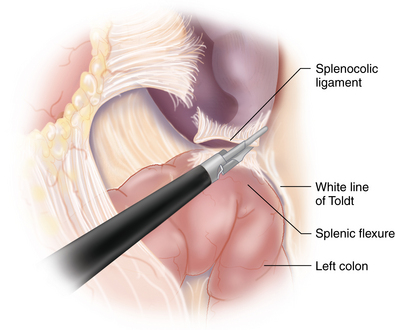

Splenic flexure mobilization

♦ The splenocolic attachments are divided with the ultrasonic dissector to further expose the inferior pole of the spleen and pancreatic tail. Depending on the patient’s anatomy, the left colon may be in the way and will need to be mobilized by dividing its retroperitoneal attachments along the white line of Toldt. Although not always necessary, the mobilization and retraction of the left colon medially may provide greater exposure of the inferior pancreatic grove in order to develop a posterior retroperitoneal plane needed during mobilization of the pancreas.

♦ The splenic attachments to the diaphragm are not divided. These attachments will provide lateral retraction to prevent the spleen from entering the operative field during extremes of patient positioning (Figure 11-2).

Pancreatic mobilization with splenectomy

♦ Pancreatic mobilization begins by dividing the retroperitoneal attachments medial along the inferior pancreatic groove just proximal to the lesion. This allows for the development of an avascular retroperitoneal plane posterior to the pancreas, which can be extended cephalad and laterally. This retroperitoneal dissection plane can be difficult to identify, especially with senescent pancreas, and gentle probing will aid in identifying the transition point from firm pancreas to loose fatty areolar tissue in the inferior pancreatic grove. As this dissection plane is developed in the cephalad direction, the splenic vessels will be encountered. The cephalad dissection is complete if the posterior gastric wall can be seen with elevation of the pancreas.

♦ The dissection continues laterally toward the tail of the pancreas. Loose areolar tissue in this plane can be divided with the ultrasonic dissector. Care must be taken to maintain a horizontal plane of dissection, as the retropancreatic space is developed to avoid injuring retroperitoneal structures such as the kidney and adrenal gland. This is usually a significant issue in the operative field when there has been extensive preoperative inflammation.

♦ If splenic preservation is to be performed, the splenic vein must be mobilized from its posterior-inferior position nestled along the pancreas. There will be numerous small venous tributaries draining into the splenic vein. Having a vessel loop around the vein will facilitate finding and dissecting these small veins. These small vessels are best divided with ultrasonic dissector, or they can be clipped with a 5-mm clip applier.

Mobilization of the pancreas in the retropancreatic plane

♦ As the splenic vein and artery are encountered during the posterior pancreatic mobilization, they should be circumferentially dissected and controlled with vessel loops. Control of these two vessels should be done proximal to the pancreatic lesion and is critical if splenic vessel preservation is considered. By having control of these vessels, hemostasis can be achieved if bleeding is encountered during distal dissection.

♦ Splenic vessel dissection can be facilitated with a right angle dissector. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the left adrenal gland, which can be intimately associated with the tail of the pancreas and cause troublesome bleeding that will make further laparoscopic dissection difficult.

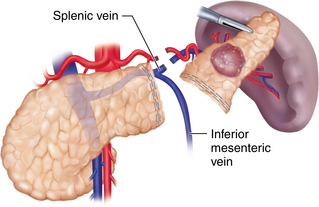

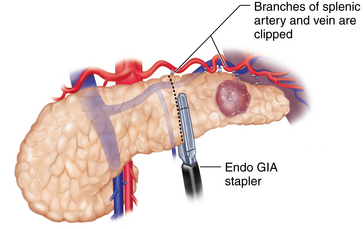

Pancreatic transection: parenchyma, splenic artery, and vein

♦ It is preferable to isolate and separately divide the splenic artery, vein, and pancreatic parenchyma. Isolation of the splenic artery can be achieved at the superior border of the pancreas using a laparoscopic right angle dissector and ultrasonic dissector. In some instances, the splenic artery is more accessible through the posterior pancreatic dissection plane. At least 1.5 cm of exposed vessel is needed for the application of an articulating 30- to 45-mm endoscopic stapler. Alternatively, endoclips and scissors can be used if the vessels are of smaller caliber. An Endoloop can be applied to the proximal stump of the artery to reinforce the endoclips. The splenic vein can also be stapled with an endoscopic 45-mm vascular stapler (Figure 11-3).

♦ Pancreas transection can be performed with either an endoscopic vascular stapler if the pancreas is soft or a reticulating Endo GIA stapler (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts) if the pancreas is thick or firm. Care must be taken to visualize the tip of the stapler prior to firing to ensure clearance of other surrounding structures including other branches of the celiac axis. Gentle and slow firing of the stapler may improve hemostasis and prevent unnecessary traumatic injury to the pancreas.

♦ The spleen is then freed of its attachments to the diaphragm and retroperitoneum, and the specimen is ready for extraction.

Pancreatic stump management

♦ The main pancreatic duct is not routinely identified within the stapled end of the pancreas. The entire end of the gland is oversewn in a running or mattressed fashion using 3-0 Prolene suture. The resection bed is then irrigated and inspected for hemostasis. The stapled splenic artery and vein ends are reinspected. The oversewn pancreatic stump is then covered with tissue sealant using a laparoscopic delivery system.

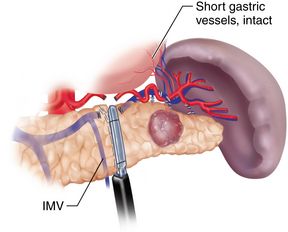

Splenic preserving distal pancreatic resection

♦ There are two methods of spleen preservation during the laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection. The first preserves the splenic artery and vein, therefore maintaining the inflow and outflow of the spleen. The second method, described by Warshaw, ligates these vessels while preserving the short gastric vessels. This method has been questioned because of a potentially higher risk of splenic infarct and the development of gastric varices (Figure 11-4).

♦ It has been demonstrated that splenic artery and vein preservation is necessary to maintain the immunologic function of the spleen. Therefore, it is our preference to preserve the splenic artery and vein with careful dissection (Figure 11-5).

Specimen removal

♦ The distal pancreas and spleen can be removed using an Endo Catch bag through a 12-mm port. The spleen can be morcellated in the Endo Catch bag to avoid having to enlarge the fascial defect at the port site. However, we find parsimonious extension of the fascial defect facilitates specimen delivery, omits the need for splenic morcellation, and does not contribute significantly to incisional morbidity or convalescence.

♦ If the procedure was done for pancreatic neoplasm, the proximal pancreatic stump of the specimen should be marked and sent for frozen section analysis by pathology. Pathologic confirmation of any potential neuroendocrine lesion also needs to be accomplished.

Drain placement and closure

♦ The resection bed is irrigated and hemostasis is checked, and a closed suction drain is inserted near the pancreatic bed and brought out through the 5-mm trocar site. The pneumoperitoneum is released and all trocars are removed under direct vision. Fascial incisions greater than 10 mm should be closed.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ The patient can be typically cared for on the regular surgical ward with intravenous fluids and pain medications.

♦ The NG tube can be removed the following day and clear liquids can be initiated as tolerated.

♦ Patients are encouraged to ambulate and use incentive spirometry as early as possible to prevent DVT and atelectasis.

♦ In the absence of a large wound, perioperative morbidities including wound infections, ileus, and cardiopulmonary compromise remain less than 20%. The overall perioperative mortality is less than 1%.

♦ Pancreatic leak remains a challenging problem in the laparoscopic approach as in the open. A surgical drain is left in place until the patient is tolerating regular diet and drain output is less than 30 mL per day. Drain fluid is not routinely sent for analysis unless there is concern for pancreatic stump leak, which can be indicated by high volume output, persistent intra-abdominal irritation manifested most commonly by fever, ileus, or lack of clinical improvement. Most leaks will stop with conservative treatment.

♦ Uncomplicated hospitalizations typically range from 3 to 5 days.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ There are several pitfalls to consider while mobilizing the medial pancreas. The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) is often located just lateral to the ligament of Treitz in the retroperitoneum at the midportion of the body of the pancreas. Attempts to save the IMV as it courses superiorly to join the splenic vein should be made to decrease the risk of splenic and portal vein thrombosis (see Figure 11-4).

♦ Dissection and control of the splenic vessels is described, where the vessels are controlled as they are encountered during posterior mobilization of the pancreas. This approach is useful for dissecting the splenic vein, but it may be more difficult for dissecting the splenic artery, depending on patient’s anatomy. If this is the case, the splenic artery can be mobilized and controlled first by dissecting along the superior pancreatic edge (see Figure 11-3).

♦ The dissection of the splenic vein is challenging because of its thin wall and numerous branches. The venous branches can usually be divided with an ultrasonic dissector without much bleeding. The one exception here is when varices are encountered. To assure optimal hemostasis, varices must be divided by the use of endoclips and not an ultrasonic dissector. If endoclips are used to control vascular branches, then care should be taken to make sure that they do not prevent the proper firing of the endoscopic stapler when dividing the main vessels.

♦ If the dissection of the vessels is difficult because of the inability to attain adequate exposure, then a hand port may be placed to facilitate exposure.

Fernandez-Cruz L, Orduna D, Cesar-Borges G, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: en-bloc splenectomy vs spleen-preserving pancreatectomy. HPB. 2005;7;2:93-98.

Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, et al. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248;3:438-446.

Leemans R, Manson W, Snijder JA, et al. Immune response capacity after human splenic autotransplantation: restoration of response to individual pneumococcal vaccine subtypes. Ann Surg. 1999;229;2:279-285.

Pryor A, Means JR, Pappas TN. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with splenic preservation. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(12):2326-2330.

Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1988;123(5):550-553.

Teh SH, Tseng D, Sheppard BC. Laparoscopic and open distal pancreatic resection for benign pancreatic disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(9):1120-1125.