Disorders of the thoracic spine

Disc lesions

Although the spine is anatomically part of the thoracic cage, we prefer to discuss the thoracic disorders in two main categories – spinal lesions (this chapter and Ch. 28) and lesions of the thoracic cage and abdomen (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen). Thoracic ankylosing spondylitis is discussed separately (Ch. 29). This is done to standardize the discussion of the spine throughout, in the hope that a better clinical understanding may result.

Introduction

Cervical and lumbar disc lesions are widely accepted as common causes of pain. For the thoracic spine, the situation is different. Although thoracic disc lesions giving rise to compression of the spinal cord are well recognized,1–5 disc protrusion resulting in pain without causing neurological signs is poorly documented.6 The incidence of thoracic disc lesions affecting the spinal cord is about one case per million people per year,3,7 usually affecting adults, although cases have been reported in children as young as 12.8 The existence of minor thoracic disc lesions provoking pain in the absence of cord compression was first established by Hochman, who removed a disc protrusion at T8–T9 in a 67-year-old lady with continuous unilateral pain in the thorax.9 Neurological signs were not present. The diagnosis was established by computed tomography (CT).

The incidence of minor thoracic disc lesions is much higher. Degenerative changes of the thoracic spine are observed in approximately half of asymptomatic subjects and 30% have a posterior disc protrusion.10 A recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study found a prevalence of thoracic disc herniations of 37% in asymptomatic subjects, disc bulging in 53% and annular tears in 58%.11 Another study of asymptomatic patients identified impressive disc protrusions in no less than 16%.12 An unexpectedly high prevalence of thoracic disc herniation (14.5%) was also demonstrated in the thoracic spines of a group of 48 oncology patients examined by MRI.13 Although these relatively high figures do not correspond to the real clinical situation, we believe that symptomatic thoracic disc protrusions are far more common than is generally accepted and agree with Krämer,14 who estimated the frequency of thoracic disc lesions to be about 2% of all symptomatic disc lesions. Recent studies also confirmed the incidence of symptomatic thoracic disc prolapses as being between 0.15% and 4% of all intervertebral disc prolapses.15,16

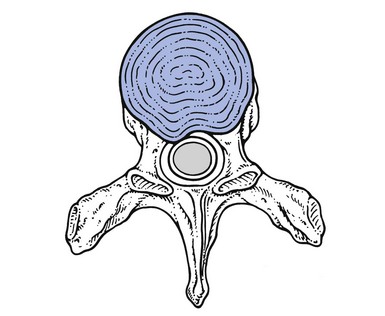

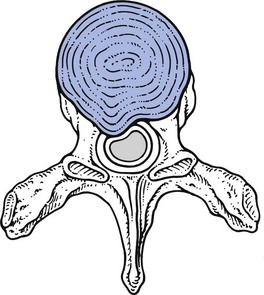

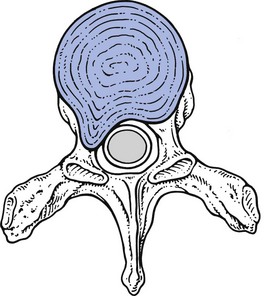

Although more frequently present than commonly believed, thoracic disc protrusions are clinically far less common than those in the lumbar spine because of the greater rigidity of the thoracic spine. This is partly a result of the stabilizing effect of the rib cage on the thoracic spine and partly due to the thoracic intervertebral discs, which are thinner on account of a less voluminous nucleus pulposus.17 Therefore extension and flexion movements are of a smaller range in the thoracic spine.

Minor thoracic disc lesions occur most often between T4 and T8. Those with cord compression are usually found in the lower half of the thorax.6,18 About 70% lie between T9 and T12, the commonest level (29%) being T11. A logical explanation for this could be that the lower segments have an increased mobility due to free ribs at these levels.19 Another reason could be that the cord has a critical vascular supply at this level.20

Clinical presentation

It is hypothesized that disc degenerations and disc displacements are of themselves painless events because the disc is almost completely without nociceptive structures. Clinical syndromes originate only when a subluxated fragment of disc tissue impinges on the sensitive dura mater or on the dural nerve root sleeve. This clinical hypothesis is extensively discussed in the lumbar section of this book (see Chs 31 and 33).

Posterocentral protrusions compressing the dura mater may provoke multisegmental pain, which is mainly referred into the posterior thorax but may also spread into the anterior chest, the abdomen or the lumbar area.21 The pain is never referred down the arm. When a posterocentral displacement increases, cord compression can result.

When the T1 nerve root is compressed by a disc lesion, pain is referred to the inner side of the arm between elbow and wrist. A T2 nerve root impingement creates pain referred towards the clavicle and to the scapular spine and down the inner side of the upper arm. The corresponding dermatomes of the T3–T8 nerve roots follow the intercostal spaces, ending at the lower margin of the thoracic cage. The dermatomes of T9–T11 include a part of the abdomen, and T11 also includes part of the groin (see Fig. 25.3).22,23

Thoracic disc protrusions may give rise to four different clinical presentations: chronic thoracic backache, acute thoracic lumbago, thoracic root pain and spinal cord compression (Cyriax:24 pp. 202–205).

Symptoms and signs

The clinical findings in symptomatic thoracic disc displacements are analogous to the lumbar and cervical disc syndromes. Again, both dural and articular signs and symptoms can be identified (see Ch. 52).

Articular signs

Examples of non-articular patterns are illustrated in Figure 27.1.

Often both articular and dural signs are present, although the latter are sometimes absent.

Pain and limitation on side flexion towards the painless side as the only positive movement does not match the pattern of a disc lesion. Other disorders, such as a pulmonary or abdominal tumour with invasion of the thoracoabdominal wall, must be considered. An intraspinal tumour – for example, a neurofibroma – is also possible (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment).

Symptoms and signs of cord compression

In thoracic disc lesions, careful attention must always be paid to abnormal neurological elements that may indicate compression of the spinal cord: pins and needles in both feet, disturbed coordination of lower limbs and positive Babinski’s sign (see Table 27.1 and pp. 165–168).

Table 27.1

Articular and dural symptoms and signs in thoracic disc lesions

| Symptoms | Signs | |

| Articular | Particular movements or postures increase the pain; others ease | Existence of a partial articular pattern |

| Dural | Pain on deep breath | Pain on neck flexion Pain on scapular movements |

Clinical types of thoracic disc protrusion

Symptomatic disc displacements in the thoracic spine may give rise to four different clinical syndromes: acute thoracic ‘lumbago’, chronic thoracic backache or ‘dorsalgia’, thoracic root pain and spinal cord compression (Figs 27.3–27.5).24 Each syndrome corresponds to a specific type of disc lesion.

Thoracic backache

Special case: self-reducing disc lesion

In this condition the disc gradually dehydrates as the result of the prolonged sitting position.25 Simultaneously, the imposed kyphosis pushes the whole intra-articular content of the disc posteriorly, compressing the dura mater and resulting in thoracic backache. On lying down, the effects of hyperkyphosis and gravity are largely diminished and the disc shifts spontaneously back into its original position. These patients should avoid prolonged anteflexion. Manipulative reduction is useless but sclerosant infiltrations may be helpful.

Acute thoracic lumbago

Recurrence may occur but the pain is not necessarily always felt at the same side.

Thoracic root pain

• In a primary posterolateral protrusion, segmental pain is felt from the start at the lateral aspect of the thorax and often radiates unilaterally to the front of the chest or the abdomen. The absence of pain in the back may lead to the discogenic origin being overlooked.

• In a secondary posterolateral protrusion, an extrasegmental posterocentral or posterior unilateral pain is initially present, which then moves more to the side and sometimes towards the anterior thorax or abdomen – meanwhile becoming segmentally referred – a sequence of symptoms that strongly suggests a secondary posterolateral disc lesion.

Both types of root compression give rise to segmental referred pain. This has a unilateral band-shaped distribution that follows the intercostal nerves. At the thoracic level a posterolateral protrusion seldom gives rise to pins and needles. If present, they follow the same segmental distribution as the pain. As the T12 dermatome spreads into the lower abdomen, interference with this nerve root can result in pain and occasionally pins and needles in the groin and/or the testicles.26

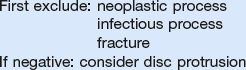

A T1 root palsy is detected during the clinical examination of the cervical spine. It is seldom the result of a disc protrusion but usually the outcome of a serious disorder such as a superior sulcus tumour of the lung, a neurofibroma or vertebral metastases. Although T1–T2 discoradicular compressions with neurological deficit have been reported,27–29 it should be kept in mind that if a neurological deficit of T1 is present, more severe disorders should always be excluded first (see see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment).

Thoracic disc lesions compressing a nerve root do not usually resolve spontaneously, although there are a few reports of spontaneous regression at a lower thoracic level.30,31 However, posterolateral thoracic disc protrusions which cause root pain remain reducible by manipulation, no matter how long they have existed. Where manipulation has failed or where neurological deficit is present, a sinuvertebral block should be given.

Compression of the spinal cord

The spinal cord is most vulnerable at the lower thoracic levels, between T9 and T12,29,32 because the spinal canal is at its narrowest there and the vascularization is at its most critical.33 It has been suggested that signs of cord compression do not always stem from pressure on the cord itself, but rather are the result of interference with the blood supply.3–5

Osteophytes narrowing the spinal canal are an extra contributing factor.34 Previous injury to the thoracic spine can also play a role in the later development of cord compression, although this circumstance is rare.

History

Pain

Initially almost all patients complain of pain. It is never particularly severe, often has a vague band-shaped distribution, and may sometimes disappear completely.35–38 It is usually localized in the back, although it may radiate into the pelvis or groin and down the legs. Occasionally, patients complain of subumbilical pain.1 The quality varies from a constant, dull and burning pain to – exceptionally – a lancinating, cramping and spasmodic pain.

Numbness

Later in the course, unilateral or bilateral numbness may set in and may be accompanied by a motor palsy. The numbness is more a diminution of normal sensation than a complete loss of sensitivity. It often starts at the big toe and is accompanied by a subjective sensation of coldness.3

Functional examination

Some or all of the following neurological signs may be present:

• Disturbed coordination with spastic gait.

• Increased muscle tone, with the affected muscles not limited to one myotome.39 Occasionally, weakness of the lower abdominal muscles can be demonstrated, when the umbilicus is seen to move as the patient attempts to sit up.1 This is known as Beevor’s sign.

• Weakness and/or atrophy of some lower limb muscles.

• Hyperreactive patellar or Achilles tendon reflexes with ankle clonus.

• Occasionally, absent tendon reflexes, particularly and inevitably when a flaccid type of paraplegia is present. The abdominal reflexes are often absent or diminished, most commonly in both lower quadrants. All these signs may be unilateral or bilateral.

• Positive Babinski’s and Oppenheim’s signs.

• Absence of the cremasteric reflex.

• Limitation of straight leg raising, sometimes bilateral.2

• Occasionally, a Brown–Séquard syndrome in cord compression.6 It is characterized by an ipsilateral flaccid segmental palsy, together with an ipsilateral spastic palsy below the lesion, with ipsilateral anaesthesia and loss of proprioception and loss of appreciation of the vibration of a tuning fork. Contralateral discrimination of pain sensation (analgesia) and thermoanaesthesia may be present and are both sited below the lesion.40,41

Sometimes the neurological disturbances are found to extend proximal to the territory of the level of compression. This may be the outcome of interference with the blood supply of the anterior spinal artery rather than compression on the cord as such.3–5

Technical investigations

The clinical description given above necessitates further imaging investigations. A plain radiograph sometimes shows calcification in the disc that is at fault.1,6,29,42 However, other authors, including Cyriax, consider calcification, together with the accompanying narrowing of the intervertebral joint space, to be non-specific.43

A myelogram usually indicates the level of the lesion with certainty, although special projections may be needed.44

Today, MRI is the imaging method of choice in the investigation of the thoracic spinal canal.45 It provides a good-quality image over the entire length of the spine and can assess the morphology of the discs and cord. It is non-invasive, has comparable sensitivity to conventional myelography in visualizing lumbar nerve roots, and allows overall assessment of the spinal canal even in the presence of cerebrospinal fluid block.46,47

Treatment

Manipulation

Contraindications

Relative contraindications

Techniques

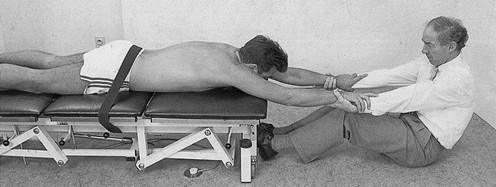

Principle of strong traction

No one can foresee with absolute certainty the direction in which the protruded fragment will move during a manipulation. Theoretically, it could be displaced further towards the spinal cord. To avoid this and for a number of other beneficial effects (see p. 256), traction is always incorporated in thoracic manipulation.

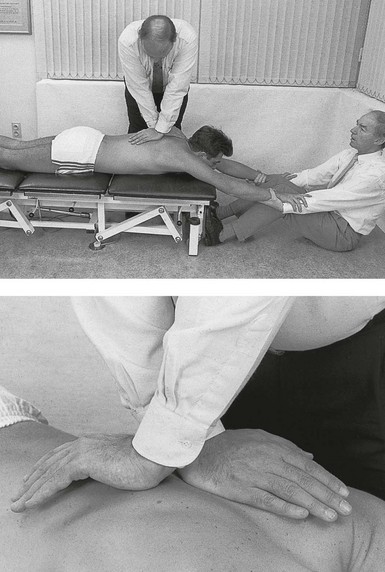

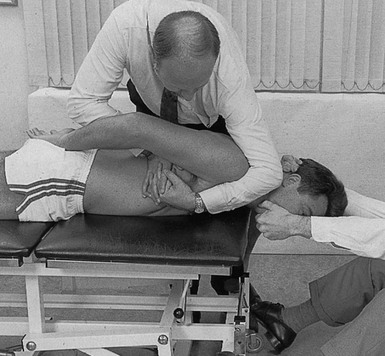

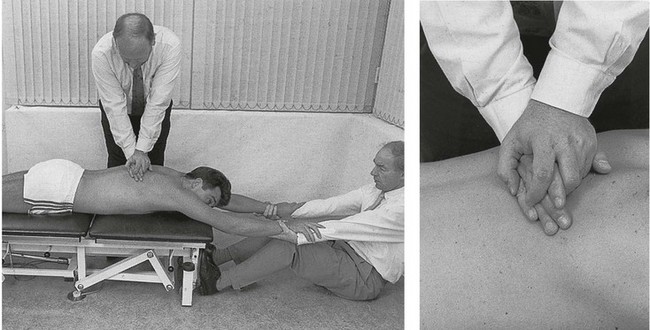

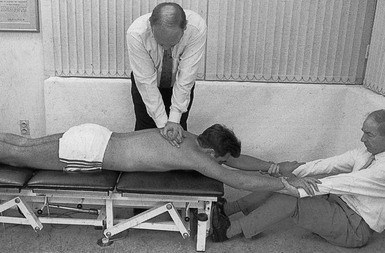

Traction is normally provided by one assistant who sits beyond the patient’s head and takes hold of either the head or the hands. Stabilization of the pelvis is provided either by a second assistant sitting at the patient’s legs and holding the ankles or by a fixation belt around the pelvis (Fig. 27.6). Whether traction is given via the head or the arms depends on the level of the lesion and the patient’s comfort. As traction on the arms opens the intervertebral joints only from T6 downwards, traction must be given via the head in disc protrusions above T6 (Fig. 27.7).

Traction via the head is provided by putting one hand under the patient’s chin and the other below the occiput, with the head and neck always kept in the neutral position (see Fig. 27.7). Both hands pull equally hard.

Extension techniques in prone position

Identifying the level of the lesion

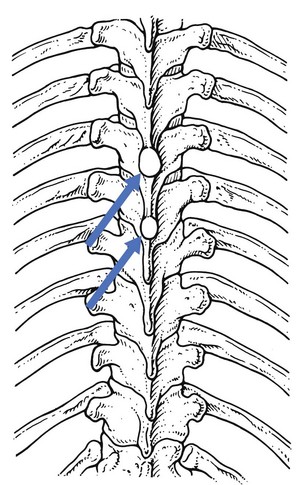

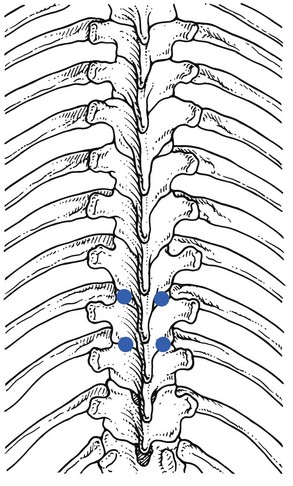

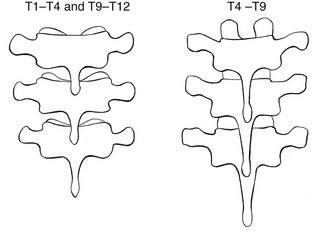

Some extension techniques are executed on the transverse processes. To be able to perform these manipulations at the right level, it is essential to have a good knowledge of the relationship between the spinous processes and their corresponding transverse processes, because this varies with the level (Fig. 27.8).

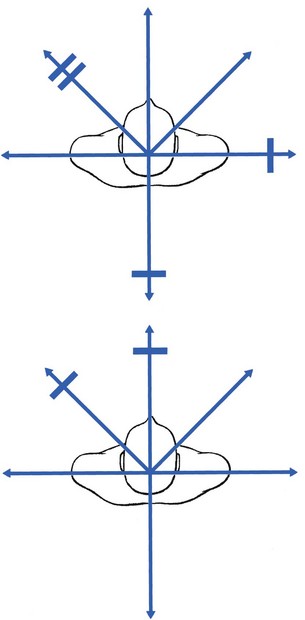

• T1–T4 and T9–T12: there is a difference of one level between the consecutive vertebrae, i.e. the transverse process of one vertebra lies level with the spinous process of the vertebra above. For example, the transverse process of T3 lies level with the spinous process of T2.

• T4–T9: there is a difference of  levels. The transverse process lies level with the interspinal line between the spinous processes of the first and the second vertebrae above (Fig. 27.9). The transverse process of T8, for example, lies between the spinous processes of T6–T7, that of T9 between T7–T8.

levels. The transverse process lies level with the interspinal line between the spinous processes of the first and the second vertebrae above (Fig. 27.9). The transverse process of T8, for example, lies between the spinous processes of T6–T7, that of T9 between T7–T8.

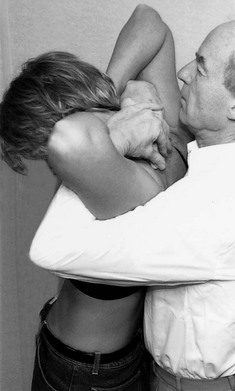

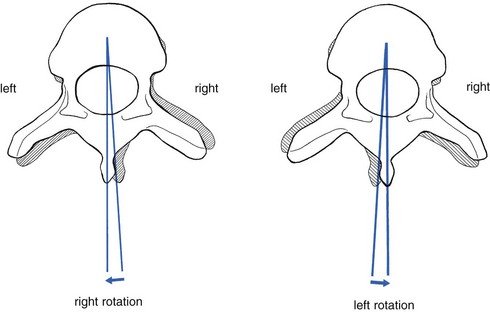

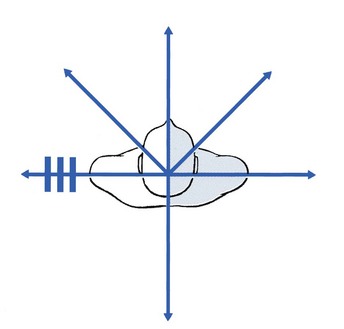

Direction of rotation

The direction of the rotation is always defined by the direction in which the anterior part of the upper vertebra rotates. So when the upper vertebra rotates to the left, the movement is defined as a left rotation (Fig. 27.10).

Fig 27.10 Direction of rotation.

Technique I: central pressure (Fig. 27.11)

Fig 27.11 Central pressure.

Technique II: unilateral pressure (Fig. 27.12)

This manipulation is performed unilaterally on the transverse process.

Fig 27.12 Unilateral pressure.

Extension technique in supine position

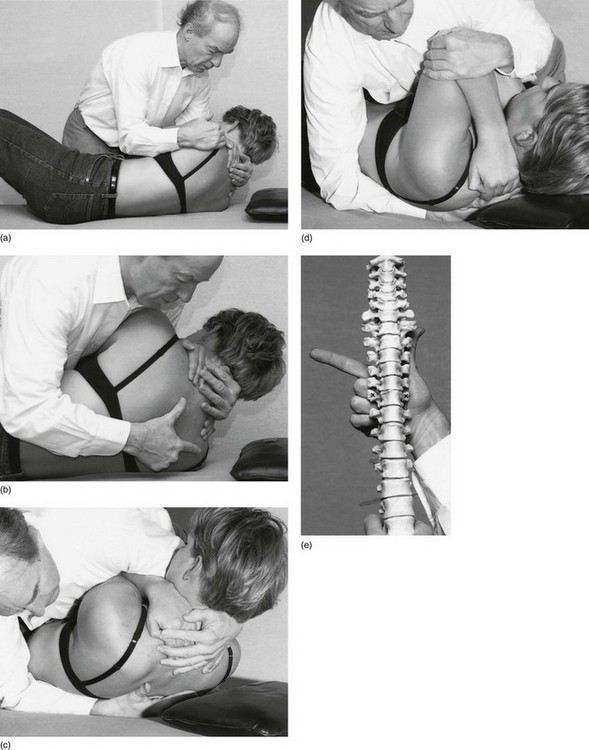

The patient lies supine just near the edge of the couch and places both hands behind the neck, the fingers covering the upper thoracic spinal processes. The elbows are placed well forwards and close together. The manipulator stands on the right-hand side facing the patient. By grasping the patient’s left shoulder in the right hand and both elbows on the left hand (Fig. 27.14a), the manipulator flexes the patient’s neck and trunk and rolls the upper body inwards (Fig. 27.14b).

Then a fist is made with the middle, ring and little fingers of the right hand – thumb and index finger are left out. This fist is now brought into firm contact with the lower vertebra of the segment being manipulated – the thenar eminence against the left and the middle phalanx of the flexed middle finger against the right transverse process. In this way the spinous process of the lower vertebra lies in the groove between these two eminences (Fig. 27.14c).

Now the patient is lowered back again until the manipulator’s hand is wedged between the patient and the couch. In order to achieve full control over the movement, the patient’s elbows are firmly held against the manipulator’s sternum (Fig. 27.14d). Leaning well over the patient and using the weight of the trunk, the manipulator obtains considerable separation at the intervertebral joint. At the moment when the limit of tissue tension is felt (and the patient relaxes as fully as possible), the manipulator pushes the body forwards to apply a certain amount of overpressure. At that moment a ‘click’ or ‘snap’ is nearly always heard and felt, and the result of the manipulation is then assessed.

Choice of manœuvre

Improvement is indicated by pain, which is perceived over a small area and/or which becomes less severe. Another important sign is centralization of the pain: pain that first spreads far distally or laterally, but becomes more centrally localized, is regarded as an improvement.48,49 Manipulations are stopped as soon as the pain has disappeared and the clinical examination becomes negative. A total number of 5 (elderly) to 10 (younger patients) manipulations are executed during one session. These can be repeated daily, although for the elderly it is advisable to allow 3 or 4 days in between. It may take 3–5 sessions before the patient has fully recovered. A certain amount of after-pain is sometimes present. If there is a recurrence, the patient should return as soon as possible to be manipulated again.

Failure of manipulative reduction

Ninety-five percent of thoracic disc lesions are reduced in 3–5 sessions. If, after 3–5 manipulative sessions, relief of symptoms is not obtained, it should be accepted that either the diagnosis is wrong or the disc lesion is not suitable for manipulation. The latter may be the result of too large a protrusion, as shown by the presence of neurological deficit, or may occur when a nuclear disc lesion is present (Box 27.2).

Oscillatory techniques

Some cases respond better to oscillations. These consist of gentle high-frequency mobilizations at 2–3 vibrations per second. Oscillations should be given for 10–15 minutes daily and are performed as either central or unilateral pressure to the thoracic spine.50

Indications

There are three groups of indications:

• Patients who present with a great deal of discomfort but with very minor articular signs on clinical examination.

• Patients with acute thoracic lumbago who are in such pain that they cannot tolerate normal manipulations. Oscillatory techniques can be used until the pain is reduced to a level at which normal manipulations can be started.

• Patients who cannot tolerate the extension or rotation techniques.

Sustained traction

In some patients with thoracic disc protrusion, reduction by means of traction may be needed. However, traction may be technically impossible in patients suffering from orthopnoea, asthma or hiatus hernia or who have recently undergone thoracic or abdominal surgery (see Ch. 40).51

Indications

• Central protrusions: it can be dangerous to manipulate very central protrusions, as there is a possibility of causing compression of the spinal cord. Central protrusions are present mainly in those with a marked thoracic kyphosis, either postural or after a wedge fracture. These patients complain of central pain radiating to both sides.

• Failure of manipulation: patients suffering from a disc lesion in whom manipulative attempts have failed or who have been made worse, should receive traction unless nerve root compression with neurological deficit is present. There is usually a history of gradual onset, although this is not pathognomonic in the thoracic spine for a nuclear protrusion.

• Symptoms of cord compression in the absence of signs: patients suffering from a thoracic disc protrusion with pins and needles in both feet can undergo cautious traction if no other symptoms or signs of cord compression are present.

• Thoracic postural pain syndrome: these patients can be helped by daily sustained traction with increasing traction-free intervals (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment).

• Disc lesions at a very kyphotic thoracic joint.

• Disc lesions adjacent to a wedge fracture of a vertebral body.

• Anterior and lateral erosion (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment).

• Lateral recess stenosis (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment).

Technique

Traction is given daily over 30–45 minutes. Thoracic discs above T9 are treated with cervical traction. For these, the rules of cervical traction should be observed (see Ch. 11).

For thoracic protrusions below T9, traction is given using the lumbar technique (see Ch. 40). An intensity of 35 kg (small person) to 70 kg (heavy, well-built person) is used. Obviously, the thoracic belt should be placed cranial to the level of the lesion. The initial traction sessions are used as the manipulator’s guide for positioning the patient and for the strength to be used.

Surgery: removal of protruded discs

The main indication is early cord compression by a progressive disc lesion.

Laminectomies done before 1960 were dangerous interventions with disappointing results.52,53 It was found that almost all serious complications occurred among those having midline protrusions at levels T10–T11.53 This is probably the outcome of the shape of the spinal canal, which is quite narrow at this level. The posterior approach used required some displacement of the cord in a very confined space, with consequent considerable risk to the blood supply.

Since 1960 a transthoracic lateral approach has been used and in recent years more progress has been made with new thoracoscopic microsurgical techniques.54,55 They seem to give better results and fewer complications.56 Recently, percutaneous laser disc decompression – intervertebral discs are treated by reduction of intradiscal pressure through laser energy – has also been promoted as a valuable method in treating recalcitrant thoracic disc lesions.57

Prevention of recurrence

Postural prophylaxis

All the rules on prophylaxis for the lumbar spine are also applicable here (see Ch. 40). However, it is much more difficult and sometimes even impossible to put them into practice. For example, it is impossible to obtain the equivalent of lumbar lordosis because even the most flexible person cannot get beyond a straight line in full extension. The most hazardous movements are those that include combined flexion and rotation elements. Lifting a weight at the same time makes them even more dangerous. Therefore patients should avoid rotating their trunk but must turn their body around using their legs and should bend their knees to lift.

Sitting for a prolonged period in a kyphotic posture must also be avoided.

Ligamentous sclerosis

In those patients in whom the risk of recurrence is high (thoracic hyperkyphosis), or when recurrence is frequent, local reinforcement is needed for the supraspinal and interspinal ligaments and for the capsules of the facet joints of the vertebrae between which the protrusion lies. This can be achieved by infiltrating a sclerosant solution into these structures, which leads to proliferation of fibroblasts and formation of new collagen.58 The final result is increased stability of the disc fragment because the two vertebrae become less mobile. Before this procedure is undertaken, full reduction must be achieved.

References

1. Benson, M, Byrnes, D, The clinical syndromes and surgical treatment of thoracic intervertebral disc prolapse. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57B(4):471–477. ![]()

2. Albrand, O, Corkill, G, Thoracic disc herniation. Treatment and prognosis. Spine. 1979;4(1):41–46. ![]()

3. Carson, J, Gumpert, J, Jefferson, A, Diagnosis and treatment of thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1971; 34:68–77. ![]()

4. Bhole, R, Gilmer, R, Two-level thoracic disc herniation. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1984; 190:129–131. ![]()

5. Shaw, N. The syndrome of the prolapsed thoracic intervertebral disc. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975; 57B(4):412.

6. Skubic, JW, Kostuik, JP. Thoracic pain syndromes and thoracic disc herniation. In: The Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. New York: Raven Press; 1991:1443–1461.

7. Ridenour, TS, Haddad, P, Hitchon Piper, J, et al, Herniated thoracic disks: treatment and outcome. J Spinal Disorders. 1993;6(3):218–224. ![]()

8. MacCartee, C, Griffin, P, Byrd, E, Ruptured calcified thoracic disc in a child. J Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A(6):1272–1274. ![]()

9. Hochman, M, Pena, C, Ramirez, P, Calcified herniated thoracic disc diagnosed by computerized tomography. J Neurosurg 1980; 52:722–723. ![]()

10. Matsumoto, M, Okada, E, Ichihara, D, et al, Age-related changes of thoracic and cervical intervertebral discs in asymptomatic subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(14):1359–1364. ![]()

11. Wood, KB, Garvey, TA, Gundry, C, Heithoff, KB, Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine. Evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77A(11):1631–1638. ![]()

12. Awwad, EE, Martin, DS, Smith, KR, Jr., Baker, BK, Asymptomatic versus symptomatic herniated thoracic disc: their frequency and characteristics as detected by computed tomography after myelography. Neurosurgery. 1991;28(2):180–186. ![]()

13. Williams, MP, Cherryman, GR, Husband, JE, Significance of thoracic disc herniation demonstration by MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13(2):211–214. ![]()

14. Krämer, J. Intervertebral Disc Diseases. Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prophylaxis. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1981.

15. Arce, CA, Dohrmann, GJ, Herniated thoracic disks. Neurol Clin 1985; 3:383–392. ![]()

16. Stillerman, CB, Chen, TC, Couldwell, WT, et al, Experience in the surgical management of 82 symptomatic herniated thoracic discs and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1998; 88:623–633. ![]()

17. Bradford, D, Juvenile kyphosis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1977; 128:45–55. ![]()

18. Winter, R, Siebert, R, Herniated thoracic disc at T1–T2 with paraparesis. Spine. 1993;18(6):782–784. ![]()

19. Pal, B, Johnson, A, Paraplegia due to thoracic disc herniation. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(861):423–425. ![]()

20. Ikegawa, S, Nakamura, K, Hoshino, Y, Shiba, M, Thoracic disc herniation in spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(1):105–106. ![]()

21. Lyu, RK, Chang, HS, Tang, LM, Chen, ST, Thoracic disc herniation mimicking acute lumbar disc disease. Spine. 1999;24(4):416–418. ![]()

22. Rohde, RS, Kang, JD, Thoracic disc herniation presenting with chronic nausea and abdominal pain. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86:379–381. ![]()

23. Jooma, R, Torrens, MJ, Veerapen, RJ, Spinal disease presenting as acute abdominal pain. A report of two cases. BMJ 1983; 287:117–118. ![]()

24. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol 1, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

25. Bruckner, FE, Greco, A, Leung, AW, ‘Benign thoracic pain’ syndrome: role of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection and localization of thoracic disc disease. R Soc Med. 1989;82(2):81–83. ![]()

26. Papadakos, N, Georges, H, Sibtain, N, Tolias, CM, Thoracic disc prolapse presenting with abdominal pain: case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(5):W4–W6. ![]()

27. Hamlyn, PJ, Zeital, T, King, TT, Protrusion of the first thoracic disc. Surg Neurol 1991; 35:329–331. ![]()

28. Winter, RB, Siebert, R, Herniated thoracic disc at T1–T2 with paraparesis. Transthoracic excision and fusion – case report with 4-year follow-up. Spine 1993; 18:782–784. ![]()

29. Love, J, Schorn, V, Thoracic-disc protrusion. JAMA. 1965;191(8):627–631. ![]()

30. Morandi, X, Crovetto, N, Carsin-Nicol, B, et al, Spontaneous disappearance of a thoracic disc hernia. Neurochirurgie. 1999;45(2):155–159. ![]()

31. Coevoet, V, Benoudiba, F, Lignières, C, et al, Spontaneous and complete regression in MRI of thoracic disk herniation. J Radiol. 1997;78(2):149–151. ![]()

32. Tovi, D, Strang, R, Thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. Acta Chir Scand. 1960;41(Suppl 267). ![]()

33. Nijenhuis, RJ, Leiner, T, Cornips, EM, et al, Spinal cord feeding arteries at MR angiography for thoracoscopic spinal surgery: feasibility study and implications for surgical approach. Radiology. 2004;233(2):541–547. ![]()

34. Otani, K, Yoshida, M, Fujii, E, Thoracic disc herniation: surgical treatment in 23 patients. Spine 1988; 13:1262–1267. ![]()

35. Bohlman, H, Zdeblick, T, Anterior excision of herniated thoracic discs. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A(7):1038–1047. ![]()

36. Reeves, D, Brown, H, Thoracic intervertebral disc protrusion with spinal cord compression. J Neurosurg 1968; 24:28. ![]()

37. Ridenour, TS, Haddad, P, Hitchon Piper, J, et al, Herniated thoracic disks: treatment and outcome. J Spinal Disorders. 1993;6(3):218–224. ![]()

38. Ikegawa, S, Nakamura, K, Hoshino, Y, Shiba, M, Thoracic disc herniation in spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64:105–106. ![]()

39. Hoppenfeld, S. Aandoeningen van ruggemerg en zenuwwortels. Diagnostiek per neurologisch niveau. Utrecht/Antwerp: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema; 1984.

40. Brügger, A. Die Erkrankungen des Bewegungsapparates und seines Nervensystems, 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Fischer; 1980.

41. Bannister, R. Brain’s Clinical Neurology, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1973.

42. Crafoord, C, Hiertonn, T, Lindblom, K, Olsson, S, Spinal cord compression caused by a protruded thoracic disc. Report of a case treated with antero-lateral fenestration of the disc. Acta Orthop Scand 1959; 28. ![]()

43. Baker, H, Love, JC, Uhlein, A, Roentgenologic features of protruded thoracic intervertebral discs. Radiology 1965; 84:1059–1065. ![]()

44. Ransohoff, J, Spencer, F, Siew, F, Gage, L, Case reports and technical notes. Trans-thoracic removal of thoracic disc. J Neurosurg 1969; 31:459–461. ![]()

45. Wallace, CJ, Fong, TC, MacRae, ME, Calcified herniations of the thoracic disk: role of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in surgical planning. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43(1):52–54. ![]()

46. Pui, MH, Husen, YA, Value of magnetic resonance myelography in the diagnosis of disc herniation and spinal stenosis. Australas Radiol. 2000;44(3):281–284. ![]()

47. Francavilla, TL, Powers, A, Dina, T, Rizzoli, HV, MR imaging of thoracic disk herniations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11(6):1062–1065. ![]()

48. MacKenzie, R. The Lumbar Spine. Waikanae: Spinal Publications; 1972.

49. Donelson, R, Silva, G, Murphy, K, Centralization phenomenon: its usefulness in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine 1990; 15:211. ![]()

50. Maitland, G, Brewerton, D. Vertebral Manipulation. London: Butterworth; 1977.

51. Grieve, G. Contra-indications to spinal manipulation and allied treatments. Physiotherapy. 1989; 75(8):445–453.

52. Vallo, MB, Ransohoff, J. Thoracic disc disease. In The Spine, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982:500.

53. Perot, P, Munro, D, Transthoracic removal of midline thoracic disc protrusions causing spinal cord compression. J Neurosurg 1969; 31:163–165. ![]()

54. Regan, JJ, Mack, MJ, Picetti, GD, III., A technical report on video assisted thoracoscopy in thoracic spinal surgery. Preliminary description. Spine 1995; 20:831–837. ![]()

55. Rosenthal, D, Dickman, CA, Thoracoscopic microsurgical excision of herniated thoracic disc. J Neurosurgery 1998; 89:224–235. ![]()

56. Sasani, M, Ozer, AF, Oktenoglu, T, et al, Thoracoscopic surgical approaches for treating various thoracic spinal region diseases. Turk Neurosurg. 2010;20(3):373–381. ![]()

57. Haufe, SM, Mork, AR, Pyne, M, Baker, RA, Percutaneous laser disc decompression for thoracic disc disease: report of 10 cases. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7(3):155–159. ![]()

-level difference between the spinous and transverse processes, which is present in T4–T9.

-level difference between the spinous and transverse processes, which is present in T4–T9.