Chapter 26. Disorders of the spine

Cervical spine

Acute disc prolapse

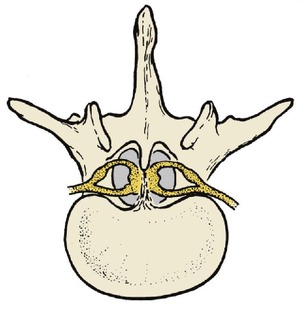

The cervical spine is very flexible and the intervertebral discs are subjected to considerable strains. The cervical roots cross the discs as they leave the spinal canal, where they are vulnerable to pressure from disc protrusion (Fig. 26.1). Disc protrusions in the neck are usually more lateral than those in the lumbar spine and affect one level only.

|

| Fig. 26.1

Cervical disc protrusion compressing a cervical root.

|

As in the lumbar spine, disc protrusions are accompanied by pain, altered sensibility and weakness. The four lowest roots are most often affected and are accompanied by pain and sensory symptoms in the radial side of the forearm and hand, with weakness of grip (C8) and elbow flexion (C5–6).

Movement of the cervical spine is also restricted, particularly flexion and rotation on the affected side.

Treatment

Conservative treatment. Analgesics, rest, a collar and traction will usually produce a remission of symptoms but the pain may be so severe and intractable that disc excision is required as an urgent procedure.

Operative treatment. Disc excision may relieve pain and improve neurological function but it makes the cervical spine more unstable than the corresponding operation on the lumbar spine and the root can still be irritated even when the disc has been excised. To avoid this, operation is sometimes accompanied by a cervical fusion in which a block of bone is inserted between the adjacent vertebral bodies. The role of cervical fusion, which puts greater strain on the intact discs, is controversial.

Cervical spondylosis

Cervical and lumbar spondylosis are almost universal in patients over the age of 40 but seldom cause symptoms.

Spondylosis is different from osteoarthritis because it occurs around intervertebral discs instead of in synovial joints (Fig. 26.2). The posterior facet joints are synovial joints and may develop osteoarthritis but the cartilage joints between the vertebrae cannot do so because they have no joint space. For practical purposes, however, the two conditions can be considered together and treated as degenerative joint disease.

|

| Fig. 26.2

Cervical spondylosis. The patient also has congenital fusion of C2 and C3.

|

Patients with cervical spondylosis feel a dull pain in the neck radiating across the shoulders and down the upper part of the arm, worse on movement. The pain can be confused with supraspinatus tendinitis and other shoulder disorders.

Treatment

The standard treatment consists of heat, rest, anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics and a supporting collar. When the symptoms have subsided, mobilizing exercises to restore movement are important but it must be said that no properly conducted scientific study has ever shown that these exercises influence the natural history of the disease. Voltaire may have been right when he commented that ‘The efficient physician is the man who successfully amuses his patients while Nature effects a cure’.

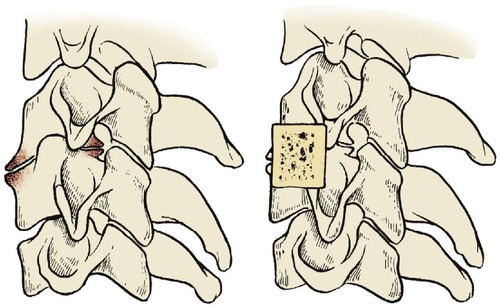

Operation is seldom required for spondylosis but may be necessary if there is severe pain arising from a single identifiable level (Fig. 26.3).

|

| Fig. 26.3

Cervical fusion. A bone block prevents movement and holds the affected vertebrae apart.

|

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis, which is so destructive to the small joints of the hands and feet, also affects the cervical spine (Fig. 26.4). The atlantoaxial joint is especially at risk because of the complex synovial folds around the transverse ligament of the atlas. If this ligament stretches, the atlas and head can slip forwards and the odontoid process presses against the cervical cord, producing quadriparesis.

|

| Fig. 26.4

Rheumatoid arthritis of the spine with forward displacement at several levels.

|

This is especially important to anaesthetists. The mouth will not open easily if the temporomandibular joint is affected. If the neck is also stiff, endotracheal intubation is difficult and the manipulation of the neck needed to intubate the patient is hazardous. Accordingly, patients with rheumatoid arthritis must always have the cervical spine examined radiologically before undergoing anaesthesia. All staff, particularly those in the recovery room, should be aware of the potential hazards of flexing a rheumatoid neck.

Treatment

A supporting collar is usually sufficient but atlantoaxial fusion may be needed if there is a neurological deficit or unremitting pain.

Acute torticollis

Severe and acute neck pain can be due to many things, including acute disc prolapse, muscle spasm, injury to an osteoarthritic facet joint, inflamed lymph nodes or an undiagnosed cervical dislocation.

Treatment

Treatment depends upon the cause. Most acute stiff necks settle with a collar, warmth and analgesia but serious injuries must be excluded first.

Cervical rib

A vestigial ‘rib’ of bone or fibrous tissue can run from C7 to the first true rib. When such a rib is present the lowest part of the brachial plexus runs across it and neurological symptoms in the arm may result. Pain down the inner side of the arm in the T1 distribution should raise suspicions of a cervical rib.

Treatment

Excision may be necessary if radiographs demonstrate a complete or incomplete cervical rib; conservative treatment with physiotherapy to improve the power of the shoulder girdle muscles has been ineffective. The operation is straightforward but the root of the neck is ‘tiger country’ and the operation must only be done by a surgeon who is very familiar with this area.

Congenital short neck (Klippel–Feil syndrome)

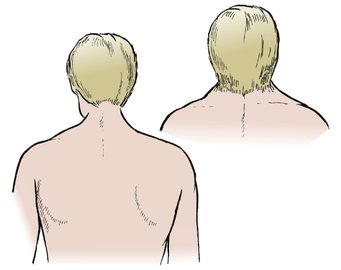

Klippel–Feil syndrome consists of a very short neck with fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae and restricted cervical movement (Fig. 26.5). The condition may be familial and is sometimes associated with scoliosis. Richard III (‘Deform’d, unfinish’d, sent before my time into this breathing world, scarce half made up’) may have had Klippel–Feil syndrome.

|

| Fig. 26.5

Klippel–Feil syndrome. A short webbed neck with low hairline.

|

Treatment

No specific treatment is required but the scoliosis may need correcting.

Congenital high scapula (Sprengel’s shoulder)

Sprengel’s shoulder is a congenital deformity in which the scapula is small and abnormally high (Fig. 26.6). The condition may be bilateral. No cause is known except that there is a failure of development of the shoulder and the muscles attached to it and it is often associated with congenital spinal anomalies.

|

| Fig. 26.6

Sprengel’s shoulder. A high fixed scapula.

|

Treatment

Some improvement in position follows release of the muscles along its upper border if carried out at an early age.

Congenital hemivertebra

Congenital hemivertebra (Fig. 26.7) and other anomalies also occur and may be associated with neurological abnormalities.

|

| Fig. 26.7

Congenital hemivertebra. There is an extra vertebra and rib on the right side.

|

Neuralgic amyotrophy

Neuralgic amyotrophy is an odd condition which is probably due to a patchy demyelination of the brachial plexus. The symptoms may follow vaccination. Like meralgia paraesthetica, this condition is important because it has neurological features that may be confused with a spinal disorder.

Characteristic features are:

1. Sudden severe pain down the arm, similar to that of a disc protrusion.

2. Paralysis of parts of the shoulder girdle as the pain eases. The nerve to serratus anterior is said to be involved most frequently, producing a true winged scapula.

3. Muscle wasting is seen in the affected area.

Treatment

The pain usually resolves without treatment over a period of weeks, but the weakness may take up to 2 years to recover. Apart from reassurance and excluding other disorders, no treatment is required.

Acute stiff neck

Not all pain in the neck is due to a disc protrusion or cervical spondylosis. An acute stiff neck, perhaps due to a small muscle tear or a derangement of the facet joints, can occur for no apparent reason.

Treatment

The symptoms usually resolve spontaneously over a period of days or weeks. A supporting collar eases the pain and manipulation is sometimes helpful.

Torticollis in children

See page 363.

Lumbar spine

Back pain

In any one year, more working hours are lost from back pain than from any other medical condition. Back problems therefore take up much of the medical profession’s time. As many as 25% of referrals to some orthopaedic clinics are for back pain.

It is a bad principle to operate on a painful back unless a definite mechanical cause has been identified. In the past, painful backs were operated upon far too often and the results were poor. Many patients were no better and some were made worse by operation. Spinal surgery, particularly spinal fusion, earned a bad name, richly deserved because operation was often followed by severe pain and stiffness which disabled the patient more than the original condition.

Back pain alone is not an orthopaedic problem. It is best managed conservatively by departments of physical medicine and rheumatology, and to refer every patient with back pain to an orthopaedic surgeon is a little like referring every patient with headache to a dentist. Unfortunately, patients with backache are frequently referred to orthopaedic clinics for historical reasons.

Spinal surgery, however, is definitely an orthopaedic problem and many surgeons with a specialist interest in the spine also treat the painful spine. The spine should only undergo operation for anatomical lesions proven beyond doubt, which limits the common indications to the following conditions:

Indications for spinal operations

• Disc excision for proven disc protrusions with neurological signs.

• Instability caused by spondylolisthesis or unstable discs.

• Scoliosis, kyphosis and other spinal deformities.

• Some tumours and infections.

Acute back strain

Acute pain in the back radiating down to the knee but not beyond and without neurological abnormality is usually due to an acute muscle or ligament strain in the lumbar spine. The symptoms can be precipitated by a sudden violent movement or by a comparatively trivial movement following a period of hard work when the muscles are stiff.

Tall slim people with willowy backs and weak muscles are said to be especially prone to acute back strains, as are those in sedentary occupations, such as medicine, who live a life of ease during the week and punish themselves at the weekend with excessive gardening.

Those who sit for a long time and then have to lift heavy weights without an adequate ‘warm-up’, e.g. carriers who may drive for more than an hour with the spine flexed in a bumpy vehicle and then leap out of their seat to lift a heavy weight from the back of the van, are also very vulnerable.

The sacroiliac joints are also said to be subject to acute strains, but without conclusive proof. The joints have a large surface area, they have poor mechanical cohesion and violent twisting strains can cause severe pain around them.

Prevention

The ‘strain’ is usually the result of incorrect lifting and most can be avoided. Workers who have to lift heavy weights, including nurses who lift patients, should be taught correct lifting techniques (Fig. 26.8). Four principles are important:

|

| Fig. 26.8

Incorrect and correct lifting. Keep the weight close to the body and the back straight. Lift with the knees.

|

Correct lifting technique

1. Do not lift with the spine flexed; in this position, the weight is hanging on taut ligaments and stretched muscles, which makes them vulnerable to additional load. Instead, lift with the lumbar spine extended.

2. Keep the weight to be lifted as near to the body as possible. The further the weight is from the body, the more effort that has to be expended in lifting it.

3. Lift with the knees, not the back muscles.

4. Make the job as easy as possible. Ensure that there is good access to the load, if possible split it into lighter loads but, if it cannot be split, share the job with two or more people.

In the workplace, lifting can be made easier by storing goods at waist height and avoiding the need for a twisting motion while lifting or carrying or by using lifting equipment and conveyor belts.

Treatment

The following measures form the standard treatment for acute back injuries and are reliable; rest, analgesics and gradual mobilization are the most important:

1. Rest.

2. Analgesics.

3. Heat.

4. Gradual mobilization.

5. Lumbosacral brace.

6. Manipulation.

Rest. The patient should rest in the most comfortable position possible, which is usually on the back or side with the knees flexed. If lying in bed is painful it is perfectly acceptable to rest in a comfortable chair.

Analgesics. Any analgesic or NSAID can be used. Narcotics such as pethidine should not be needed.

Heat, either from a hot water bottle or a heat pad, is very comforting for pains arising from muscles and ligaments and the diagnosis should be reconsidered if heat does not help. The mechanism of relief is obscure, but is probably nothing more than old-fashioned counterirritation. Even if unscientific, patients find warmth helpful.

Gradual mobilization. As the pain subsides, gradual mobilization can be started, but the patient must be prevented from lifting weights and risking further injury for at least 6 weeks. This may be difficult if the patient is a hardworking self-employed worker who needs to get back to work to earn a living. It is nevertheless essential if recurrent strains are to be avoided.

Mobilization of the spine is important. If a full range of spinal movement can be achieved, it is likely that the muscle or ligament has healed and the presence of a full range of movement ensures that loads can be borne equally throughout the spine.

If movement is limited, further injury is probable. The stiff areas of the spine are more likely to be injured by sudden stress and the mobile areas will be taking more strain than normal. A good range of movement should therefore be achieved before the patient returns to work, and the range of movement maintained by an exercise routine.

Lumbosacral brace. If the patient insists on returning to work before full movement has returned, a lumbosacral support will lessen the risk of recurrence. A brace will support the back when the patient is lifting and, perhaps more important, will ‘remind’ patients of their condition so that they lift correctly.

Spinal supports should be worn only for pain relief or to protect the back when it is at greatest risk. If they are worn permanently the spine will become stiff, the muscles will take less strain, and further injury becomes more likely.

Manipulation. Manipulating an acutely painful back is occasionally harmful if there is some underlying undiagnosed pathology but is sometimes dramatically successful, particularly if the sacroiliac joint is affected. Manipulation is a skill which takes much training and should not be attempted by the inexperienced. Both osteopaths and chiropractors are skilled manipulators.

Differential diagnosis

There are two serious conditions that can masquerade as an acute back strain:

1. A lumbar disc protrusion. This can be easily distinguished from a back strain because the pain extends below the knee and is accompanied by neurological symptoms such as numbness, weakness or altered sensibility below the knee (p. 16). Always check sensibility, power and reflexes distal to the knee.

2. Spinal tumours, particularly metastases. Radiographs are essential to exclude tumours in the vertebrae if there is any doubt.

Recurrent back strains

Patients suffering recurrent back strains should seek the help of a rheumatologist or specialist in rehabilitation rather than an orthopaedic surgeon.

Treatment

Operations have no place in the management of recurrent back strain. All the measures described for the management of acute back strains should be used, with special attention to prevention. Spinal fusion will make matters worse unless the disc is also unstable.

Prolapsed intervertebral disc

Anatomy

The discs are not solid lumps of inert gristle resembling rubber pads, as patients often think, but living structures which flatten slightly during the day and re-expand at night. They consist of a firm nucleus pulposus surrounded by the annulus fibrosus, a ring of fibrocartilage and fibrous tissue which links the two vertebrae together. The disc is a symphysis between each pair of vertebrae and, with the two posterior facet joints, allows movement between the vertebrae.

The tension within the disc is maintained by fluid imbibition at the cellular level. If imbibition fails for any reason, the pressure within the disc falls, the disc collapses, increased movement occurs between the adjacent vertebrae, the annulus fibrosus is exposed to increased stress and this is accompanied by vague low back pain. CT scans can demonstrate the lesion, and injection of saline or contrast medium may reproduce the back pain.

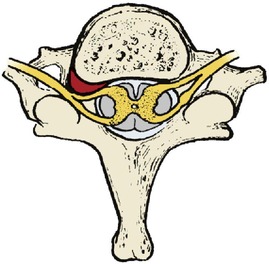

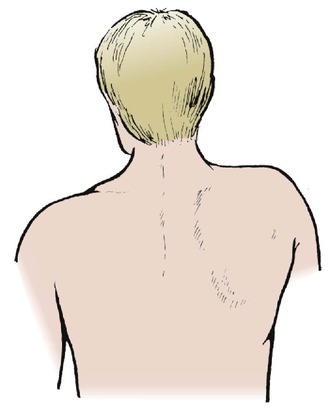

As degeneration proceeds, the annulus fibrosus softens and the degenerate disc bulges the annular ligament backwards, usually just lateral to the midline (Fig. 26.9). If this occurs in a tight spinal canal opposite a nerve root, the function of the root is affected.

|

| Fig. 26.9

Disc prolapse and root compression at the L4–5 junction. A laterally placed prolapse may compress the L4 root, a more central prolapse will compress L5 and a central prolapse the cauda equina. Osteophytes in the lateral canal will also produce root compression.

|

Ninety per cent of lumbar disc protrusions involve the lowest two spaces, L4–5 or L5–S1. Lesions which press on the L5 root cause altered sensibility on the outer side of the calf and weakness of the peronei and ankle extensors, while those affecting the S1 root produce altered sensibility on the foot or back of the calf, weak ankle flexors and a depressed ankle jerk. The resting muscle tone of the glutei, hamstrings, calf muscles and other posterior muscle groups may also be reduced and these muscles may waste.

Clinical features

Unless there are neurological symptoms and signs below the knee, the patient probably does not have a true prolapsed intervertebral disc. Disc lesions seldom cause severe back pain and it is quite wrong to use the term as a synonym for acute back strain.

Straight leg raising, which stretches the nerve, is restricted by pain. Other tests which stretch the nerve are also positive (p. 17).

Be wary of patients with no straight leg raising; the nerve root is not stretched until the leg is lifted 30°, and pain before this level is reached is more likely to be caused by apprehension, hysteria, malingering, or one of the conditions listed below. Beware also of the patient who can lean forward and touch the toes on the couch yet has restricted straight leg raising. These features are not compatible with a simple organic disorder.

Investigations

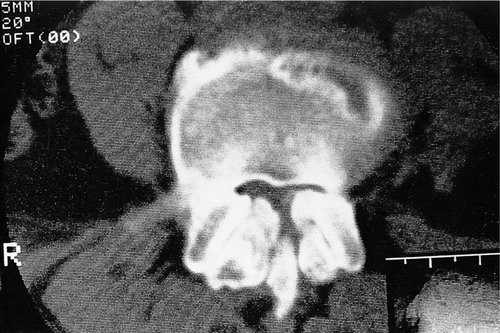

It is helpful to know the exact site of the lesion if operation is planned. MRI (Fig. 26.10) is the mainstay of treatment, but radiculography (Fig. 26.11) or CT (Fig. 26.12) can be used.

|

| Fig. 26.10

MRI scan of a prolapsed intervertebral disc at L5–S1.

By kind permission of the MRIS Unit, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.

|

|

| Fig. 26.11

Radiculogram showing a disc prolapse on the right side.

|

|

| Fig. 26.12

(a) CT scan showing prolapsed disc material compressing the spinal contents. (b) A normal CT scan for comparison.

|

Differential diagnosis

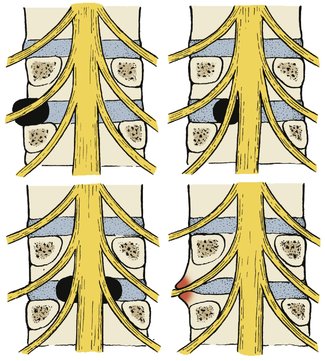

Any condition that causes root irritation or pain in the leg can be mistaken for a disc prolapse, including the following conditions:

Differential diagnosis of prolapsed discs (Fig. 26.13)

1. Tumours within the spinal canal.

2. Neurofibromas in the root canal.

3. Ependymoma and other tumours.

4. Intracranial tumour.

5. Ankylosing spondylitis.

6. Intrapelvic mass.

7. Osteoarthritis of the hip.

8. Spondylosis.

9. Malingering.

10. Vertebral tumours.

11. Tuberculosis.

12. Infective discitis.

13. Intermittent claudication.

|

| Fig. 26.13

Differential diagnosis of disc prolapse. OA, osteoarthritis.

|

Treatment

Left untreated, the symptoms disappear spontaneously even if the protrusion remains. In other patients, the annulus fibrosis will rupture and disc material will be extruded into the spinal canal. This may make the symptoms either dramatically better or dramatically worse.

In patients over the age of 40 a plain radiograph should always be obtained and routine investigations carried out to exclude a spinal tumour and systemic disease before any treatment is started. The incidence of positive findings in patients between the ages of 20 and 40 is so low that some radiologists believe a preliminary radiograph is unnecessary until conservative treatment has failed, but most cautious doctors will wish to see a radiograph at some stage.

Conservative treatment. Because some natural recovery is likely, it is wrong to operate without a fair trial of conservative treatment unless there is a cauda equina lesion (p. 455). Treatment consists of two main measures:

1. Rest, analgesics and muscle relaxants.

2. Traction.

Rest. The patient should stay in bed in the most comfortable position with adequate analgesia and, if necessary, muscle relaxants such as diazepam 5 mg twice daily. Bed rest should be total, in hospital if possible. Total bed rest at home is a formidable undertaking that places a great strain on the family. Most patients defy instructions and get up for meals and toilet purposes.

Traction helps to keep the patient in bed and some say that is all it does. It may also relieve muscle spasm and pain but it does not ‘replace the disc’.

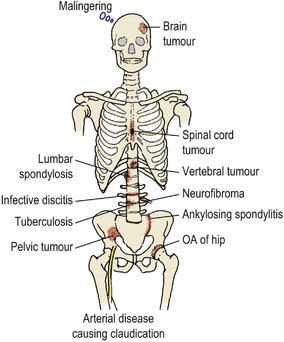

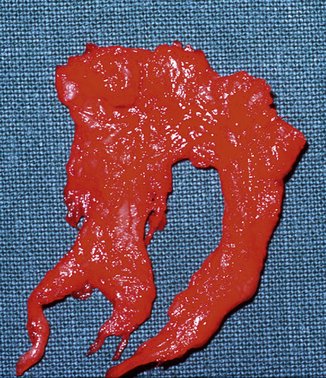

‘Putting the disc back’. Manipulation of spines with acute disc prolapse is very dangerous. While osteopathic and chiropractic manipulations are excellent for chronic back problems, manipulation in the presence of neurological symptoms and signs can rupture the annulus fibrosus, extrude disc material and cause severe neurological damage. The concept of ‘putting the disc back’ by manipulation, as if it were a piece of jigsaw, is firmly rooted in the public mind and is quite wrong; a prolapsed disc is not a firm, rounded lump of gristle shaped like a ‘Smartie’, but looks more like a piece of soggy string (Fig. 26.14). Discs do not pop in and out like the cuckoo on a cuckoo clock (Fig. 26.15).

|

| Fig. 26.14

Prolapsed disc material. The degenerate disc material is soft and soggy.

|

|

| Fig. 26.15

Prolapsed discs are soft, as in Figure 26.14. They do not pop in and out of place like a cuckoo in a clock.

|

At operation, the disc will usually extrude itself from the disc space under pressure when the annulus fibrosus is excised, and to imagine that these discs can be replaced by manipulation is a fallacy.

Operative treatment. There are four indications for considering operation on prolapsed discs:

1. No improvement in the symptoms and signs after 6 weeks of rest.

2. An increase in the neurological deficit.

3. Bladder or bowel involvement suggesting a cauda equina lesion.

4. Intractable pain.

If operation is considered, a CT or MRI scan is needed to demonstrate spinal nerve roots and identify the disc protrusion. If the site of the disc protrusion matches the clinical signs, the disc can either be softened by chymopapain injection or excised surgically.

Chymopapain injection (chemonucleolysis). Injection with chymopapain, a proteolytic enzyme found in pawpaws and used commercially as a meat tenderizer, is suitable for discs that are also ideal for surgical excision. It is not helpful for patients with chronic disc lesions and no neurological signs. If the indications are correct, chymopapain injection is effective in about 70% of patients and in some centres has replaced surgical excision of the disc.

The injection must be done under image intensifier control on an inpatient basis and is accompanied by quite severe back pain. There is also a small incidence of anaphylactic reaction. Chymopapain injection is successful in the short term but there is some evidence that the long-term results are less satisfactory than surgical treatment; however, the morbidity is still less than that of disc excision.

Disc excision is done either by neurosurgeons or by orthopaedic surgeons. The disc is approached from behind after excising the ligamentum flavum and, if necessary, the inferior portion of the lamina overlying the root. This procedure is called fenestration (from the Latin fenestra, a window). All disc material should be removed, including any that has sequestrated into the spinal canal.

Disc excision relieves neurological symptoms in about 75% of patients, provided that it is done in the right patients and for the right indications; i.e. neurological symptoms that match the neurological signs and a radiologically proven disc protrusion. The physical signs of muscle weakness and loss of reflexes do not always return to normal after laminectomy and disc excision.

The operation disturbs the ‘triple joint’ between neighbouring vertebrae and their facet joints. Without a complete disc, the bodies move towards each other and put unnatural stresses upon the posterior facet joints, which then degenerate. This is an unavoidable problem and some degree of stiffness and back pain can be expected in 30–60% of patients after a disc prolapse, whether it is treated conservatively, surgically or by chemonucleolysis with chymopapain.

Microdiscectomy. Discs can be excised through small skin incisions or under endoscopic control. The technique is new and difficult but the results are encouraging. The recovery period is shorter and surgical trauma is minimized.

Cauda equina lesions

A very small proportion of discs rupture in the midline of the annulus fibrosus instead of in the lateral recesses and produce a cauda equina lesion with the following clinical features:

• Painless retention of urine.

• Perianal anaesthesia.

• Bilateral sciatica.

If these signs are present, there is no place for conservative management and the disc must be removed surgically as an emergency. Failure to do this can result in a disabling and permanent cauda equina lesion.

High lumbar discs

Disc protrusions at levels above L4 are uncommon and produce unusual physical signs. Any patient with back pain and a neurological deficit higher than L5 should be investigated by a neurologist in case a spinal tumour is present.

Treatment

The treatment and indications for operation are the same as those for protrusions at lower levels, although excision is needed more often because the canal is relatively narrow in the upper part of the lumbar spine.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is an inflammatory disease of joints which involves the sacroiliac and spinal joints before others. The HLAb27 gene is commonly found. The disease is commonest in young men and should be considered in any man between 15 and 30 years of age with the following features:

• Diffuse low back pain or pain in a root distribution without neurological signs.

• Stiffness of the back worst in the morning.

• Chest expansion less than 5 cm.

• Raised ESR.

• Erosions of the sacroiliac joints.

• A rapid response to anti-inflammatory drugs.

• A family history of ankylosing spondylitis.

• Painless effusions in a large joint.

Treatment

Untreated, the whole of the spine from coccyx to occiput can become a single rigid bar and it is important to maintain motion. Ankylosing spondylitis is best managed by a rheumatologist. Treatment of the acute attack is similar to rheumatoid arthritis, with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs followed by mobilization. In the longer term, regular physiotherapy to maintain motion is essential.

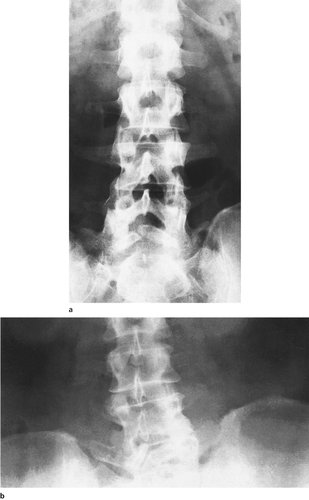

Lumbar spondylosis

Lumbar spondylosis is present to some extent in everybody over the age of 40. Few have symptoms even when the radiographs show the characteristic changes of an osteophyte on the anterior lip of the vertebral body and disc space narrowing (Fig. 26.16).

|

| Fig. 26.16

Lumbar spondylosis.

|

In advanced spondylosis, the lumbar spine is grossly abnormal, with large osteophytes, narrowed disc spaces and sclerotic vertebral bodies.

The symptoms of spondylosis are like those of degenerative joint disease elsewhere: pain or aching after activity, and loss of movement.

Treatment

Unless there is a neurological deficit due to nerve root compression, surgery has no place in the management of lumbar spondylosis, which is best treated in a department of physical medicine.

Operation is not needed unless there is root entrapment. The following conservative measures are usually sufficient to relieve symptoms:

1. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs.

2. Physiotherapy to restore as much mobility as possible.

3. A lumbosacral brace to support the spine, just as a wrist support will help an osteoarthritic wrist.

4. Encouraging the patient to maintain the range of movement that they have and to learn to accept their disability.

Root entrapment

Osteophytes can encroach upon the root canal and cause root compression. The symptoms and signs are similar to those of an acute disc prolapse but less acute and less well localized. Investigation requires MRI or a CT scan (Fig. 26.17).

|

| Fig. 26.17

CT scan of the lumbar spine showing narrowing of the root canal due to osteophytes.

|

Treatment

If the nerve root lesion can be localized, the root can be unroofed to decompress the nerve, but the osteophytes are likely to recur and decompression does not improve the underlying spondylosis and osteoarthritis of the facet joints.

Spinal stenosis

The width of the spinal canal in normal individuals varies greatly. Some patients have narrow canals which can be made still narrower by osteophytes, disc prolapses or other space occupying lesions. A narrow spinal canal is also present in achondroplasia.

If the spinal canal is very narrow, congestion of the cord and roots can occur with exercise and this can cause pain in the buttocks and legs. The symptoms are usually brought on by extension of the spine when standing or walking and are eased by flexing the spine or sitting. The symptoms have much similarity with intermittent claudication, and the condition is sometimes known as ‘spinal claudication’.

Investigation

CT scans and MRI demonstrate the constriction in the spinal canal very clearly.

Treatment

Conservative treatment is often helpful and consists of weight reduction, a spinal support and physiotherapy to reduce hyperextension of the lumbar spine.

If these measures fail, operation to decompress the spinal cord is usually needed. A wide laminectomy will produce relief but symptoms can recur if soft tissue forms around the site of laminectomy.

Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis

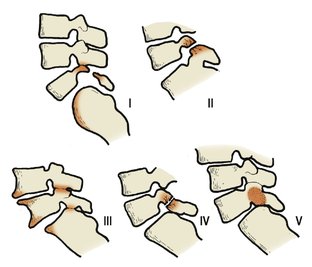

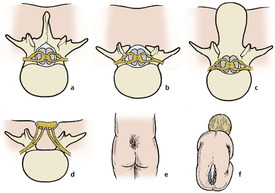

Spondylolisthesis is such a wonderful word that there is a temptation to use it whenever possible. In fact, it means only ‘vertebral slipping’ and must be distinguished from spondylolysis which means a ‘broken vertebra’. There are several causes of spondylolisthesis (Fig. 26.18). The different types are classified as follows, using Roman numerals:

I Dysplastic – a developmental anomaly at the lumbosacral junction.

II Isthmic – a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis.

III Degenerative – degenerative osteoarthrosis.

IV Traumatic – acute trauma.

V Pathological – weakening of the pars interarticularis by a tumour, osteoporosis, tuberculosis or Paget’s disease.

|

| Fig. 26.18

Types of spondylolisthesis: I, dysplastic; II, isthmic; III, degenerative; IV, traumatic; V, pathological.

|

Dysplastic. A congenital deficiency of the lumbosacral facets allows the L5 vertebra to slip forwards off S1 (Fig. 26.19). The pars interarticularis becomes attenuated and may break. This is a rare condition, commoner in girls than boys, and causes severe hamstring spasm (p. 351).

|

| Fig. 26.19

Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of a dysplastic spondylolisthesis. On the anteroposterior view, the fifth lumbar vertebra looks as if it was viewed from above. Upside down, it looks like Napoleon’s hat on a totem pole.

|

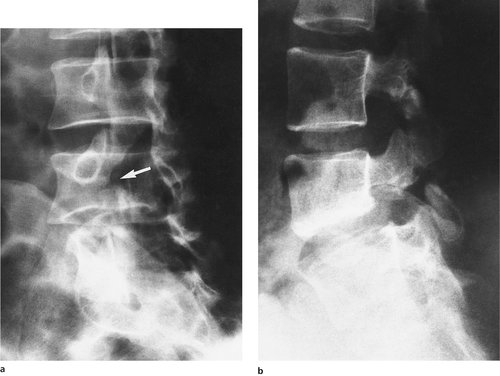

Isthmic. The most common type of spondylolisthesis is slipping at a spondylolysis of the pars interarticularis caused by a fatigue fracture (Fig. 26.20). The condition is common in young vigorous patients, particularly athletes who hyperextend the spine, e.g. javelin throwers and fast bowlers, and presents with a dull low back pain radiating to the buttocks. The cause is obscure. Five per cent of the normal population have a spondylolysis by the age of 5 but this figure rises to 6% in adults so it cannot all be the result of hyperextension or violence on the sportsfield.

|

| Fig. 26.20

(a) Isthmic spondylolisthesis. Note the defect ( arrowed) in the pars articularis. (b) Isthmic spondylolisthesis of L5–S1 and spondylolysis of L4.

|

The midline of the spine is tender at the lumbosacral junction and a step can usually be felt at the affected level. Neurological signs are absent unless there is root compression at the site of the lesion.

Radiographs show a defect (spondylolysis) in the pars interarticularis which separates the back and front halves of the vertebra and allows the vertebral body to slip forwards, producing a spondylolisthesis. The defect is most easily seen on oblique films.

Degenerative. Vertebral slipping can result from mechanical wear of the posterior facet joints, but in this condition there is no spondylolysis and the main problem is degenerative joint disease. It is commonest in women over the age of 55.

Traumatic. In exceptional cases, the slip can be due to an acute traumatic fracture (see Fig. 10.32).

Pathological. Both tumours and osteoporosis can weaken the pars interarticularis enough to allow the upper vertebra to slip forwards.

Treatment

Restriction of activity, a lumbosacral support for use when the back is painful and exercises to build up the extensor muscles of the spine are all helpful.

This is one of the few spinal conditions that may be helped by operation. Operation is indicated if conservative measures are not effective or there is progression of the slip in a growing child. An intertransverse fusion to link the two separated halves of the affected vertebra is simple and reliable.

Osteochondritis

Scheuermann’s disease

Scheuermann’s disease is described on page 331. The ring apophyses of the vertebrae are affected and growth at the front of each vertebra is arrested. The condition affects children, usually boys, between the ages of 13 and 16 and produces a smooth rounded kyphosis. The condition is usually painless even while it is active.

Treatment

If the kyphosis is severe, bracing may be effective, and in very severe cases a spinal fusion may be needed. It is not kind to keep urging the children to ‘stand up straight’ because they are unable to do so.

Calvé’s disease

Calvé’s disease (p. 331) probably does not exist but it was described as a collapse of the immature vertebral body and assumed to be an osteochondritis. Some cases may perhaps be due to osteochondritis, but tuberculosis and spinal tumours cause the same appearance and are more serious.

Congenital anomalies

Minor congenital anomalies of the vertebrae are exceedingly common but seldom have serious consequences.

Lumbarization and sacralization

The boundary between the lumbar spine and sacrum is not always precise. In some patients L5 may have a large transverse process either articulating with or fused to the sacrum (partial sacralization) or S1 may be separate from the sacrum (sacralization). Some patients with these abnormalities have back pain but there is no hard evidence that the abnormalities themselves cause pain. Nevertheless, the presence of pain at the site of a congenital anomaly is often regarded as strong circumstantial evidence.

Treatment

Patients with transitional lumbosacral vertebrae should be treated as if their radiographs were normal, using anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy. Operation on the anomaly should be avoided.

Congenital hemivertebra

A hemivertebra leaves the patient with a lateral kink in the spine, which causes a compensatory scoliosis above and below. This may itself cause root irritation and throw greater strain on the small joints of the spine (Fig. 26.21).

|

| Fig. 26.21

Hemivertebra of the lumbar spine.

|

Treatment

Physiotherapy and analgesics are usually sufficient, but the hemivertebra may need to be excised if the deformity or the symptoms are severe.

Spina bifida

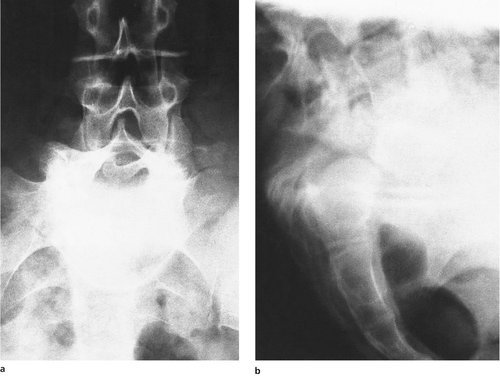

As many as 20% of the population have radiological spina bifida occulta without serious symptoms (Fig. 26.22), perhaps accompanied by a small hairy patch or lipoma at the lumbosacral junction or a minor neurological deficit (Fig. 26.23). Others have myelocoele, meningocoele or meningomyelocoele with exposed spinal nerve roots due to a failure of tubulation of the spinal cord, and these patients have serious problems in the neonatal period and early childhood (p. 356). Between these two extremes there is a spectrum of pathology.

|

| Fig. 26.22

Spina bifida occulta: (a) affecting the fifth lumbar vertebra; (b) with a hemivertebra at the lumbosacral junction.

|

|

| Fig. 26.23

Types of spina bifida: (a) normal; (b) spinal bifida occulta; (c) meningocoele; (d) meningomyelocoele with exposed nerve roots; (e) hairy patch at lumbosacral junction; (f) neonate with meningomyelocoele.

|

Treatment

The management of severe spina bifida in children is described on page 356.

Diastematomyelia

Some congenital abnormalities of the lumbar spine include a fibrous band or bony bar which tethers the spinal cord. As growth proceeds, the spinal cord is stretched and neurological signs appear (Fig. 26.24). Children between 5 and 10 years are most often affected. The sacral roots are the first to be involved, causing pain in the foot and a high arch to the foot. Later, numbness develops and the foot becomes flat as the sacral roots are more seriously damaged.

|

| Fig. 26.24

Diastematomyelia. A fibrous or bony bar splits the spinal cord.

|

Any child with unexplained pain in the feet or legs, particularly with a progressive foot deformity, should be suspected of having a diastematomyelia. A plain radiograph may demonstrate a bony abnormality and a CT scan or MRI may show a fibrous tether. The opinion of a neurological surgeon is helpful.

Treatment

Less severe manifestations are best treated conservatively unless there is evidence of tethering of the roots by bony bars or fibrous bands, which should be divided or excised by a neurological surgeon.

Other conditions

Spinal tumours

Metastases

The commonest spinal tumour is a metastasis and the possibility of a tumour must always be remembered when treating any patient with back pain, even if the history is long. A history of back pain from other causes does not bring immunity to spinal tumours and it is quite possible for a patient with established back pain of many years standing to develop a bone tumour in addition to the original problem. Any painful back should be examined radiologically if a metastasis is suspected, even though making the diagnosis of a spinal tumour does not always help the patient. An ESR is useful: if normal, a metastasis is unlikely.

The commonest tumours to metastasize to the spine are those which usually spread to bone:

1. Prostate.

2. Breast.

3. Kidney.

4. Bronchus.

Metastatic tumours commonly go to the pedicles, which are destroyed. This can easily be recognized radiologically by looking for an owl in each vertebra on the anteroposterior view. The pedicles correspond to the eyes and the spinous process to the beak. If a pedicle is destroyed, its outline cannot be seen. Beware the winking owl!

Primary tumours

Other bone tumours are seen in the spine, including osteoblastoma and giant cell tumour, but osteogenic sarcoma, which occurs typically around the growing end of long bones, is very rare. Tumours of the nervous system, such as neurofibroma and meningioma, also occur and multiple myeloma may cause vertebral collapse.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a very common condition, particularly in women after the menopause, and causes a dull low back pain with a gradually increasing kyphosis (p. 320). Pathological fractures and sudden collapse of a vertebral body can follow a trivial injury, or even just coughing.

Treatment

Apart from diagnosis and a spinal support, there is little to offer; the osteoporosis is usually too far advanced to be treatable by the time the patient is seen (p. 320).

Tuberculosis

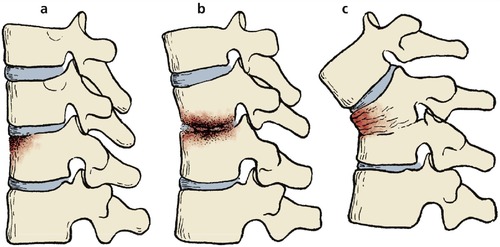

Spinal tuberculosis is now rare in developed countries but still a scourge elsewhere. The characteristic features of the disease are as follows (Fig. 26.25):

|

| Fig. 26.25

Tuberculosis of the spine: (a) early involvement of a vertebral body; (b) erosion of both vertebrae and narrowing of the disc space; (c) collapse of the vertebrae with sharp gibbus.

|

1. The patient is unwell and has lost weight.

2. The affected vertebrae are tender.

3. The disease involves the vertebral body and crosses the disc space.

4. The infection causes abscesses within the psoas sheath which point at the psoas insertion in the groin.

5. Radiologically, there is destruction of the anterior vertebral margin with wedging of one or more vertebrae and widening of the psoas sheath.

6. The vertebral collapse produces a sharp angled gibbus, which may be the first physical sign. In late cases, the gibbus may be very marked.

Complications

Complications may be serious, with the formation of sinuses, which may become secondarily infected, and paraplegia (Pott’s paraplegia), which has three common causes: (1) pus and intracellular pressure; (2) mechanical injury to the cord from bony pressure; and (3) vascular embarrassment to the spinal cord where it crosses the gibbus.

Treatment

Treatment is by oral antibacterials (p. 315), which are only effective if the patient actually takes them. The treatment must be continued for months or years. Alternatively, operation is needed to drain the pus, remove dead bone and fuse the affected vertebrae to prevent future bone collapse. If bone collapse has already occurred and the spinal cord is threatened, bone grafting and fusion is required.

Infective discitis

The intervertebral discs can become infected, often by obscure bacteria or fungi. Spread can occur directly from bone infection in adjacent vertebrae. The patients have diffuse back pain, often severe, and a raised ESR. The radiographs show erosion of bone on both sides of the intervertebral disc. Disc infections are more common in drug addicts and immunosuppressed patients.

In children, discitis can occur without any apparent infection and usually leads to painless fusion of adjacent vertebrae.

Treatment

If the organism can be identified, systemic antibiotics are effective, but exploration of the disc is sometimes necessary.

Meralgia paraesthetica

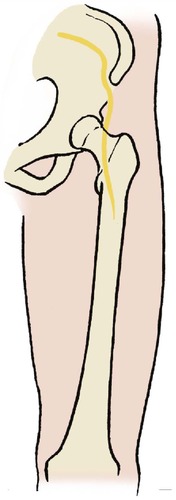

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh enters the thigh just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and may be trapped either at this point or within the abdomen (Fig. 26.26). Meralgia paraesthetica is Greek for ‘pain in the thigh with altered sensibility’ and this is an excellent description of the symptoms.

|

| Fig. 26.26

Meralgia paraesthetica. Abnormal sensibility in the distribution of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh.

|

The condition is not serious but it is important to know of it because, like disseminated sclerosis, peripheral neuritis, tabes dorsalis, subacute combined degeneration of the cord and a host of other peripheral neuropathies, it can cause neurological symptoms and signs in the leg without involvement of the spine and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of a prolapsed disc.

Treatment

The condition usually resolves spontaneously and seldom requires decompression of the nerve.

Coccydynia

The coccyx is a richly innervated structure, supposedly because it is the vestige of the tail. Whether this is true or not, there is no doubt that it is extremely sensitive to injury and that pain in the coccyx can be very difficult to eradicate.

The symptoms often begin after a fall onto the coccyx through missing a chair or falling onto the ice, but more often in accidents at work. The pain is severe and persistent and the position of the coccyx makes sitting difficult. Coccydynia can also be caused by disc prolapses and pelvic disorders, including carcinoma of the rectum and uterus, which should always be considered.

Coccydynia is more common in women than men and is more difficult to treat in neurotic and litigious individuals, who seem particularly susceptible to the condition.

Treatment

Injection with hydrocortisone is often effective but if the pain is still present after three injections, denervation of the coccyx with ultrasound or a radiofrequency probe in a pain clinic should be considered.

Coccygectomy is sometimes done but should only be considered as the last resort. It may succeed in a few patients but in many the pain remains after the coccyx has been removed.

Manipulative medicine

Osteopaths and chiropractors are skilled in manipulation and can produce remarkably good results in patients with severe pain in the neck and back. Anybody who can relieve pain is a friend of the medical profession but problems can arise if the practitioner does not look beyond the spine for the cause of symptoms, or believes that spinal manipulation can cure diseases in other structures.

Patients attending manipulative therapists without medical assessment are therefore the cause of some concern. Provided serious organic disease has been excluded, it is hard to find a reason why a patient should not be treated by an osteopath or chiropractor rather than a physiotherapist, if that is their preference.

It must be remembered that most of the conditions treated successfully by manipulation are self-limiting disorders, and experienced manipulators readily refer patients with persistent problems to orthopaedic surgeons or rheumatologists.