Chapter 22. Disorders of the shoulder and elbow

Shoulder

Recurrent dislocation of the shoulder

Acute dislocations of the shoulder are described on page 192. Although most shoulders in elderly patients remain stable after reduction, some dislocate repeatedly with trivial trauma, especially those with ligamentous laxity. The dislocations can be anterior, posterior, inferior or multidirectional, but anterior dislocation is by far the commonest.

Recurrent anterior dislocation

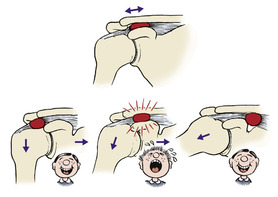

Recurrent anterior dislocation happens when the shoulder is fully abducted and externally rotated, which brings the head of the humerus against the weak inferior joint capsule (p. 193). This position, in which the arm is above the head and the hand facing forwards, occurs when swimming backstroke, reaching for a ball in a rugby line-out, or reaching into the back seat of a car from the front (Fig. 22.1). Patients with ligamentous laxity or those where there is a Bankart lesion (disruption of the anterior glenoid labrum and capsule) are most at risk.

|

| Fig. 22.1

Movements that can dislocate the shoulder.

|

Occasionally the humeral head may be fractured, giving a flat appearance or a hatchet-like deformity on radiographs (Hill–Sachs lesions).

Treatment

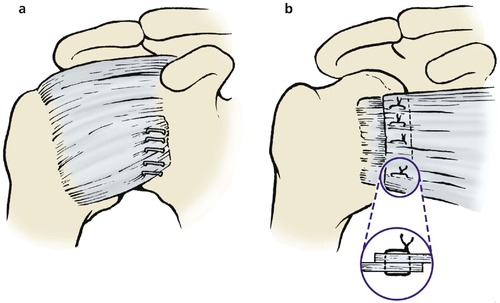

The dislocation can usually be reduced easily and many patients are able to reduce their own shoulders. Some learn to avoid dislocations and do not want operation, but others are disabled by their instability, and surgery must then be considered (e.g. Fig 22.2). Unfortunately, in young patients there is a significant chance of recurrence (up to 90%); recent trials of early surgery in these patients have shown a reasonable reduction in the subsequent dislocation rate.

|

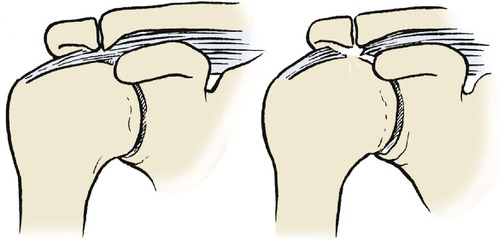

| Fig. 22.2

Operations for recurrent dislocation of the shoulder: (a) reattachment of the inferior corner of the capsule; (b) shortening of the subscapularis tendon.

|

Methods of correcting recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder include:

1. Tightening the inferior pouch of the joint capsule (by open surgery or arthroscopic surgery and/or electrocautery).

3. Tightening the subscapularis muscle to limit external rotation (Putti–Platt operation).

4. A bone block on the glenoid neck.

5. A combination of these.

After operation, the arm is bandaged to the side for 3 weeks. The forearm can then be released to allow rotation, and physiotherapy begun. The results are generally satisfactory.

Recurrent posterior dislocation

Recurrent posterior dislocation is less common than anterior dislocation and is often seen as a ‘party trick’ in teenagers with loose joints. The same patients can usually click their jaws and do weird tricks with their thumbs. The humeral head can become ‘locked’ behind the glenoid (Fig. 22.3).

|

| Fig. 22.3

Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder in a patient with a humeral head defect.

|

Acute dislocations are described on page 192.

Treatment

The basis of treatment is to tell the patients not to do it on purpose, in the hope that they will learn to avoid the movements that cause the dislocation. It is very rare for recurrent posterior dislocation to cause enough disability to warrant stabilization. If operation is required then either a posterior bone block or a glenoid osteotomy will be needed. Both these operations are formidable and very unreliable.

Internal derangements of the shoulder

The glenoid labrum, like a meniscus in the knee, can be torn or detached at its rim and cause painful clicking or catching within the joint. Lesions of the superior labrum adjacent to the biceps tendon are described as SLAP lesions (SLAP = superior labrum anterior posterior). These occur when the superior glenoid labrum is avulsed or detached from the glenoid. Loose bodies and irregularities of the articular surface produce similar catching and clicking symptoms. MRI scans and, previously, arthrograms are very useful for identifying the lesion.

Treatment

The vast majority of these lesions are now dealt with arthroscopically. Labral lesions can be reattached with sutures or absorbable fixation devices. Loose bodies and chondral lesions are easily seen and removed with the arthroscope.

Supraspinatus tendinitis

The supraspinatus tendon passes through the narrow tunnel between the acromion and the head of the humerus and may degenerate or become inflamed where it crosses the humeral head (Fig. 22.4). With the resultant impingement between the humeral head and the acromion, the affected area of the tendon swells and causes pain during active abduction. The pain goes as soon as the sensitive area has passed through the tunnel. Because the pain is present in a small arc of movement only, usually between 60 and 120° of abduction, the condition is sometimes known as ‘painful arc syndrome’.

|

| Fig. 22.4

Supraspinatus tendinitis and painful arc syndrome. An inflamed and swollen area of the supraspinatus tendon causes pain as it passes beneath the acromioclavicular joint.

|

The diagnosis can be confirmed by comparing passive movement with active. When the shoulder is moved passively there is no pressure on the tendon and movement is painless. During active movement the tendon is compressed against the humeral head and this is painful.

There are effectively three stages of this tendinitis, depending on the severity of the inflammation: stage 1, microscopic changes in the tendon; stage 2, oedema of the tendon; and finally, stage 3, where the tendon starts to rupture and tear.

Treatment

In the early stages, rest and avoidance of activities provoking the inflammation may be sufficient, but with prolonged or severe cases an injection of 25 mg of hydrocortisone acetate and local anaesthetic placed around the tendon (but not into it) is effective in most patients. The injection is given with the arm hanging and the patient sitting and supported. The needle is placed either beneath the acromion from its lateral end or posteriorly in the line of the tendon. In recalcitrant cases that fail to settle with appropriate conservative treatment, or where the supraspinatus tendon has torn, then surgery may be necessary. Arthroscopic (or open) surgery to remove the spur on the under-surface of the acromion or inferior surface of the acromioclavicular joint has a good prognosis, although the recovery for this may be prolonged. Occasionally the acromioclavicular joint needs to be excised. The aim of the surgery is to allow increased room for the inflamed tendon to pass under the acromion without impingement. By removing the cause of the impingement, the tendon will hopefully heal. Where there is a tear of the tendon this can again be repaired to bone or side to side, either arthroscopically or via an open approach. The advantage of arthroscopic procedures is the shortened recovery time postoperatively.

Acute calcific supraspinatus tendinitis

If the symptoms of supraspinatus tendinitis come on rapidly over a period of hours and the pain is intense, radiographs may show a patch of calcification within the tendon, often adjacent to its insertion on the humeral head. It is frequently described as one of the worst pains imaginable. The patients are usually in the second or third decade of life and the condition is probably a variation of crystal arthropathy (p. 305). Women are affected more often than men.

Treatment

Aspiration can be attempted but injection of hydrocortisone acetate into the calcified area itself brings dramatic relief. The calcified material may need to be excised if these methods fail.

Rupture or tear of supraspinatus tendon

The supraspinatus tendon can rupture spontaneously without causing acute symptoms (Fig. 22.5). Cadaver studies show that the tendon is defective in 40% of patients at age 40, 60% at 60 and 80% at 80, but a much smaller percentage of patients have shoulder symptoms. From this it can be concluded that many supraspinatus ruptures are asymptomatic, although some cause intermittent aching in the shoulders after the age of 40.

|

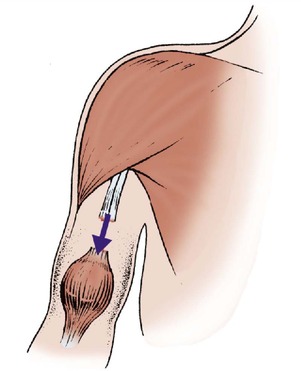

| Fig. 22.5

Attrition rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. The supraspinatus tendon becomes worn beneath an osteophyte on the acromioclavicular joint and may rupture.

|

Gradual attrition of a degenerate and ischaemic tendon on osteophytes on the under-surface of the acromion or the acromioclavicular joint is the likely mechanism (see above).

Treatment

No treatment is required in the asymptomatic, but in those patients with significant weakness of the power of abduction then a debridement of the tendon, repair of the torn portion back to the bone, and a decompression of the impingement may be required. Symptomatic relief with anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy may be effective in some patients.

Frozen shoulder

The main diagnostic feature of frozen shoulder is painful restriction of external rotation. It is a common and troublesome condition in which the shoulder is at first painful, then stiff. The stiffness makes it difficult to bring the hand to the mouth, behind the head to comb hair or behind the back to fasten buttons or hooks.

The cause is not known. There may be a precipitating cause, such as a minor injury, but there is often none. A localized autoimmune response is one possible explanation.

The condition has three distinct stages:

1. Painful phase. In the first stage, which can last for about 6 months, there is a painful restriction of movement in all directions. This distinguishes the condition from supraspinatus tendinitis, in which a specific arc of motion is painful during active movement only. The pain gradually subsides as the disease enters its second stage.

2. Stiff phase. The shoulder is very stiff, but usually painless with gross restriction of movement. This stage gives ‘frozen’ shoulder its name and lasts from 6 to 12 months. The pain gradually goes but the stiffness remains.

3. Recovery phase. During the next 6 months movement returns slowly but seldom completely.

Treatment

Treatment varies according to the stage of the disease.

Painful phase. Anti-inflammatory drugs are effective and a short course of systemic steroids may be needed for patients with severe pain. Physiotherapy is ineffective during this stage.

Stiff phase. During this phase, physiotherapy to improve the range of movement is occasionally helpful but relief is unpredictable.

Recovery phase. Physiotherapy or manipulation under anaesthetic may produce an increase in movement. Arthroscopic surgery to release the capsule has been shown to speed up the recovery.

Ruptured biceps tendon

The tendon of the long head of biceps, like that of the supraspinatus, is vulnerable at the shoulder and may rupture near its scapular origin (Fig. 22.6). The lesion occurs in older patients with minimal trauma and allows the muscle belly to contract unopposed, forming a firm ball of muscle in the lower part of the upper arm. This is sometimes called the ‘Popeye sign’ after the well known ‘sailor man’ (Fig. 22.7).

|

| Fig. 22.6

Ruptured biceps tendon allowing the muscle belly to contract into the lower part of the upper arm.

|

|

| Fig. 22.7

A patient with a ruptured biceps tendon.

|

The condition is always alarming for the patient, who feels something snap in the shoulder. There is an obvious unfamiliar lump, which soon becomes discoloured by subcutaneous bleeding.

Treatment

No treatment is required apart from firm reassurance and explanation. The soft tissue swelling and bruising gradually subsides and the short head of biceps continues to function and hypertrophies. Movement of the shoulder is little affected.

Acromioclavicular instability

Acute separation of the acromioclavicular joint may escape diagnosis until the patient presents with acromioclavicular instability. The arm is painful when working in front of the body at shoulder height, as when writing on a blackboard or carrying a tray. The joint itself is seldom tender, but a marked step at the joint is usual and can be abolished by holding the arm to the side, placing a hand under the elbow and lifting the humerus vertically upwards.

The exact clinical features depend upon the extent of the lesion.

Treatment

Surgical treatment is not required unless there is localized tenderness over the joint itself, in which case excision of the outer end of the clavicle may be needed.

Referred pain

Pain around the shoulder, particularly around the supraspinatus muscle, is often referred from the neck. The cervical spine should be examined in any patient who is complaining of pain in the shoulder.

Osteoarthritis of the shoulder

Osteoarthritis of the shoulder causes painful restriction of movement, particularly abduction and forward flexion. Movement of the scapulothoracic joint compensates to some extent, but there is often substantial disability.

Treatment

Conservative treatment with physiotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs is helpful. Joint replacement is required for severe pain and restriction of movement.

The rheumatoid shoulder

The shoulder is not designed for weight-bearing. It is therefore unfortunate that the elbows and shoulders of patients with rheumatoid arthritis must function as weight-bearing joints when the patient gets out of a chair or uses crutches. To make matters worse, the shoulder is not mechanically stable and has a large synovial cavity, features which make it susceptible to destruction by rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment

Anti-inflammatory drugs, appliances and aids are the mainstay of treatment but total joint replacement (Fig. 22.8) is required in some patients with painful or disorganized joints. Excision arthroplasty is also possible. The results of shoulder arthroplasty are good in rheumatoid arthritis.

|

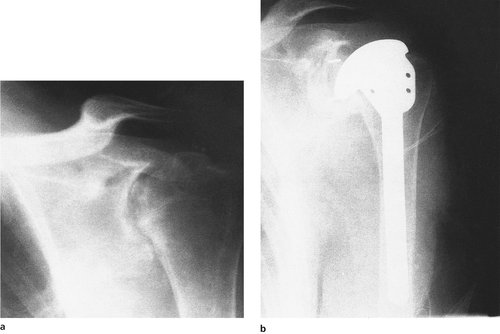

| Fig. 22.8

(a), (b) Rheumatoid arthritis of the shoulder treated by total shoulder replacement.

|

Elbow

Tennis elbow

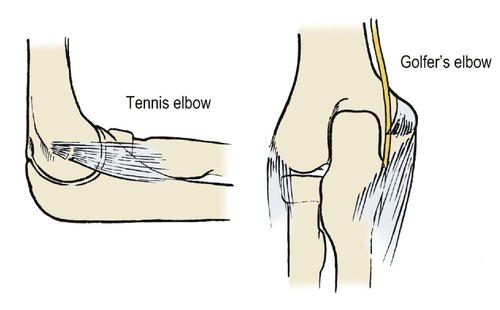

The commonest lesion of the insertion of muscle or tendon onto bone is tennis elbow in which a microscopic tear occurs in or near the insertion of the common extensor tendon on the lateral condyle and humerus (Fig. 22.9). The injury is caused by either a sharp flexion of the wrist while the extensors are contracted or, in the chronic form, by hitting a tennis ball awkwardly during a backhand stroke. It can also be caused by excessive pressure when using a racquet grip which is too small. This overuse injury also occurs in everyday activities such as gardening, lifting and painting.

|

| Fig. 22.9

Sites of muscle tears in tennis and golfer’s elbow.

|

On examination, the lateral epicondyle is tender, and stressing the extensor origin, by forcing the wrist into flexion with the extensors contracted, reproduces the patient’s symptoms (Mills’ test).

Treatment

Treatment is by rest, i.e. avoiding contraction of the extensor muscles, by an injection of hydrcortisone acetate into the tender area, or by pulsed ultrasound. It is helpful to inject 2 ml 1% lidocaine into the affected area. This helps to disperse the steroid throughout the damaged area, as well as anaesthetizing it to confirm that the injection has been placed in the correct spot. The first injection has a very approximate success rate of 75%, the second 50%, and the third 25%.

Golfer’s elbow

Golfer’s elbow is a similar condition to tennis elbow, in which the common flexor attachment on the medial epicondyle of the humerus is strained or torn. Classically, the symptoms are precipitated by the golfer striking the ground instead of the ball, thus straining the flexor origin. The condition is less common and the area of tenderness less precise than tennis elbow.

Treatment

Treatment is by steroid injection into the tender area, taking care to avoid the ulnar nerve if conservative treatment has failed. Treatment is less effective than for tennis elbow.

Loose bodies

Loose bodies in the elbow form in three ways:

1. Fragments from osteochondral fractures.

2. From chondral fragments.

3. Osteochondritis dissecans, which is much rarer at the elbow than the knee.

Clinical features

Loose bodies cause mechanical locking of the elbow (Fig. 22.10). Loose bodies in the olecranon fossa limit extension, in the coronoid fossa they limit flexion, and loose bodies stuck between the radius and ulna block pronation and supination.

|

| Fig. 22.10

Loose bodies in the elbow with early osteoarthritis.

|

Treatment

If the symptoms warrant it, the loose body must be removed either arthroscopically or via open procedure but rehabilitation is slow and some loss of movement is possible.

Olecranon bursitis

The olecranon bursa is a normal structure, comparable with the prepatellar bursa at the knee. A normal bursa is small but an inflamed or infected bursa is large, hot and painful.

In the past, olecranon bursitis was known as ‘student’s elbow’, from the notion that students spent much of their time leaning on the elbows poring over textbooks. Today, the condition is seen more often after trauma or a minor penetrating injury. It is also seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or gout, both of which can cause inflammation of any vulnerable soft tissue lesion.

Treatment

Infected bursae are treated by antibiotics and drainage, with excision of the bursa if infection recurs. Inflamed but uninfected bursae rarely require operation but excision is sometimes required if the inflammation is recurrent. Anti-inflammatory drugs should be tried first as these often resolve the condition. Gout should be treated or the bursa will recur after excision.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis of the elbow restricts flexion and extension and is disabling in patients who use their arms strenuously, e.g. blacksmiths, thatchers and steel erectors.

Treatment

Conservative treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs and alteration of daily activity is the treatment of choice whenever possible. Debridement has little to offer because the osteophytes recur after excision, and joint replacement is not effective because the prosthesis almost invariably loosens.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect both the elbow and the superior radioulnar joint. These must be considered separately.

Elbow

Pain is the main problem in the rheumatoid elbow, but flexion and extension may be restricted and the elbow may eventually become unstable. This is a special problem if the lower limbs are also involved because, like the shoulders, the elbows become weight-bearing joints when the patient uses crutches or pushes up from a chair.

Treatment. If conservative treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs fails to bring relief, surgical synovectomy may be needed. Prosthetic elbow replacements are suitable for patients with joints that are painful and who do not wish to place great physical demands upon their elbows.

Superior radiohumeral joint

The radial head is surrounded by synovium, and involvement of the superior radiohumeral joint is common. Pronation and supination are severely limited but flexion and extension may be unaffected.

Treatment. If conservative treatment is unsuccessful and the symptoms are present only on pronation and supination, excision of the radial head is effective. The operation can be combined with synovectomy of the elbow. Prosthetic replacement of the proximal end of the radius was a popular procedure but is now seldom performed either for rheumatoid arthritis or for fractures.

Case reports

Painful movement of the shoulder is common, especially in the middle-aged athlete.

Patient A

A 42-year-old keen tennis player presented with increasing pain over the right shoulder. He had noticed that over the last few months the shoulder was becoming increasingly painful with most movements above his shoulder height. Movements below shoulder were pain-free. There was no associated history of trauma, but he had recently been doing a lot of DIY activities around the home and remained a keen tennis player.

On examination it was clear that he had a painful arc syndrome with classic pain with abduction of the arm. The shoulder joint itself was stable.

Treatment consisted of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and physiotherapy to improve the rotator cuff musculature. The pain failed to settle over the next 2 months. A steroid injection into the subacromial bursa relieved the pain and he subsequently went on to an uneventful recovery, returning to playing club tennis.

Patient B

A 58-year-old gentleman who had previously been a keen sportsman presented with increasing pain and weakness of his right shoulder. No other joints were involved and it was clear that he had weakness in the power of abduction and pain with this movement.

Plain radiographs suggested a small spur on the underside of the acromioclavicular joint and sclerosis where the supraspinatous inserts into the humeral head. An MRI scan confirmed a full thickness rotator cuff tear and the patient elected for operative treatment.

The patient underwent an arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff and excision of the bony spur and an acromioplasty to decrease the risk of future impingement. After an appropriate but slightly prolonged rehabilitation programme, the patient was able to return to normal activities.

Patient C

A 22-year-old previously keen swimmer presented with increasing pain with most over shoulder activities of both shoulders, the right being the most problematic. He described no previous episodes of instability or injury. The pain had failed to settle despite stopping swimming and undergoing physiotherapy.

On examination it was noted that he had a generalized joint hypermobility and it was clear that there was evidence of glenohumeral instability with a positive sulcus sign and some apprehension with external rotation and abduction.

It was felt that this gentleman had glenohumeral instability as a result of the generalized joint hypermobility. He was referred back to physiotherapy for rotator cuff exercises; although this improved his symptoms slightly, he was unable to return to his normal sporting activities. He subsequently went on to have two episodes of instability of the shoulder joint and eventually had an arthroscopic capsular repair.

Summary

These three presentations represent reasonably common presentations of shoulder problems. Early impingement problems of the rotator cuff can be treated conservatively with physiotherapy and/or injection of the bursa with steroid. Those that fail to resolve or where there is a significant rotator cuff tear may well be treated with arthroscopic surgery and removal of the impingement lesion and repair of the cuff tear. Care should be taken to exclude those patients with a generalized joint hypermobility because these can occasionally present with similar signs, the key being the often generalized joint hypermobility that is often apparent.