24 Disorders of the Neck and Spine

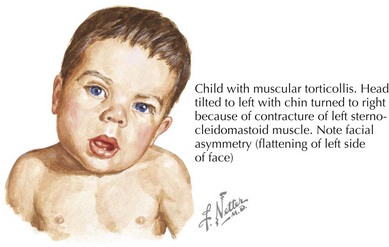

Congenital Muscular Torticollis

Torticollis, from the Latin words for “twisted neck,” is lateral neck flexion with contralateral head rotation (Figure 24-1). Although the majority of torticollis cases result from sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) shortening, other causes include neurologic conditions, cervical spine abnormalities, and vision or hearing deficits.

Evaluation of CMT should include a thorough birth history and description of presenting symptoms. The physical examination classically demonstrates an infant with the head tilted towards the side of SCM contraction with the chin pointed in toward the opposite shoulder (see Figure 24-1). A soft, nontender mass may be palpable in the body of the SCM. Visual tracking, hearing, and neurologic function should also be assessed to rule out nonmuscular causes. Patients should be evaluated for other associated conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip and referred for diagnostic imaging or surgical consultation as necessary.

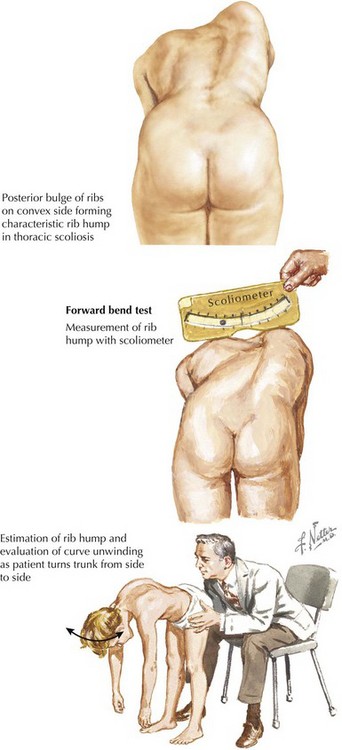

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature and rotation of the spine (Figure 24-2). Although most cases of scoliosis are idiopathic, it can also arise from congenital or neuromuscular disorders and is associated with various syndromes.

The evaluation of idiopathic scoliosis should include a careful history and physical examination. Patients are screened for thoracolumbar asymmetry with an Adam’s forward bend test and scoliometer (see Figure 24-2). Examination should include comparison of the shoulders, scapulae, trunk, pelvis, and legs. Because idiopathic scoliosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, a careful assessment of neurologic function and signs of associated orthopedic disorders should be assessed. Congenital scoliosis should not be mistaken for infantile idiopathic scoliosis because the former is associated with other osseous and visceral anomalies. Definitive diagnosis and disease severity are determined by measuring the Cobb angle on a posteroanterior spinal radiograph, with any curvature more than 10 degrees being diagnostic. MRI is typically reserved for an atypical presentation or patients with focal neurologic findings.

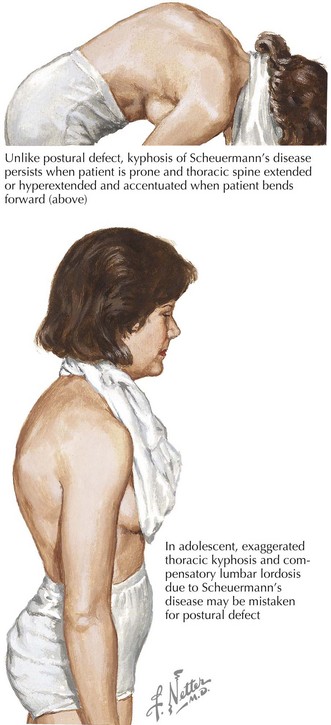

Kyphosis

Normal sagittal, thoracic vertebral kyphosis is 20 to 45 degrees by the Cobb angle on a lateral radiograph. Larger angles are pathologic and result in a rounding of the upper back or “hunchback deformity.” The most common causes are postural kyphosis and Scheuermann’s disease (Figure 24-3). Rare causes include congenital kyphosis, infection, malignancy, and other neuromuscular or osseous disorders. Postural kyphosis is mostly seen in adolescent boys as a result of slouching. There is typically no back pain nor any radiographic abnormality. Scheuermann’s disease is an idiopathic osteochondritis that is a common cause of back pain in older children and adolescents. By definition, Scheuermann’s disease results in anterior wedging of at least 5 degrees in at least three adjacent vertebral bodies.

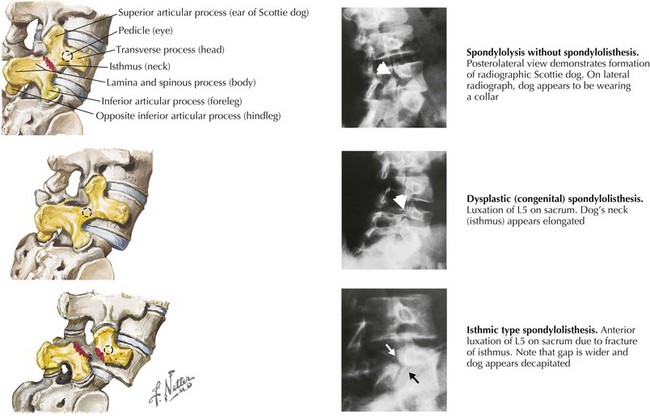

Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

Oblique vertebral radiographs in an unaffected patient demonstrate a “Scottie dog” with the transverse process as the nose, the superior articular process as the ear, the spinous process and lamina as the body, and the inferior articular process as the front leg. In spondylolysis, the dog has a fracture line through the neck (Figure 24-4). In spondylolisthesis, the entire head of the dog is displaced, with or without spondylolysis, on a scale graded from I (<25% slip) to V (complete spondylolisthesis) (see Figure 24-4). Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis most commonly occur at L5 on S1, which can be seen on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs. Radiographs are also useful in identifying the degree of slip and any associated anomalies. CT and MRI are helpful if there is an atypical presentation, if the degree of slip is severe, or for preoperative planning. A single photon emission CT scan can help distinguish an acute from a chronic pars interarticularis defect, with the latter typically requiring operative repair.

Crawford AH. Orthopedics. In: Rudolph CD, Rudolph AM, Hostetter MK, et al, editors. Rudolph’s Pediatrics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Do TT. Congenital muscular torticollis: current concepts and review of treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):26-29.

Hu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(3):656-671.

Slotkin JR, Mislow JM, Day AL, Proctor MR. Pediatric disk disease. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2007;18(4):659-667.

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1527-1537.