Chapter 71 Disorders of the Mediastinum

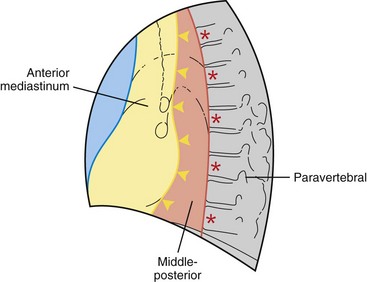

This chapter divides the mediastinum into anterior, middle-posterior, and paravertebral compartments (Figure 71-1). The anterior mediastinum is defined by an imaginary line drawn along the anterior trachea and posterior cardiac border on a lateral chest radiograph. The paravertebral compartment is located posterior to an imaginary line drawn to connect the anterior aspects of the thoracic vertebrae. The middle-posterior mediastinum is the compartment located between the anterior and paravertebral compartments. Note that the paravertebral regions do not form part of the mediastinum proper.

Overview of Mediastinal Masses

In adults, approximately 65% of primary mediastinal lesions are located in the anterior mediastinum, 10% in the middle-posterior mediastinum, and 25% in the paravertebral compartment. In contrast, approximately 38% of childhood mediastinal lesions are located in the anterior, 10% in the middle-posterior, and 52% in the paravertebral compartment (Table 71-1).

Table 71-1 Compartmental Classification of Mediastinal Disorders

| Abnormality/Source | Disorder/Abnormality |

|---|---|

| Anterior Mediastinum | |

| Disorders of thymus gland | Thymomas: thymic carcinoma, thymic carcinoid, thymolipoma, thymic cyst, thymic hyperplasia Lymphoma: Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma Germ cell neoplasms Benign: Mature teratoma Malignant: Seminoma, nonseminomatous germ cell neoplasms |

| Thyroid | Intrathoracic goiter |

| Parathyroid | Parathyroid adenoma |

| Pericardial cysts | |

| Miscellaneous | Mesenchymal neoplasms (lipoma, liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, leiomyoma) Cystic hygroma (mediastinal lymphangioma) |

| Middle-Posterior Mediastinum | |

| Lymph node enlargement | Lymphoma Benign mediastinal lymphadenopathy: Granulomatous disease, infectious (tuberculosis, fungal infections) Noninfectious (sarcoidosis, silicosis) Miscellaneous causes: Castleman disease Amyloidosis Metastatic mediastinal lymphadenopathy Lung, renal cell, gastrointestinal, and breast carcinoma |

| Cysts | Foregut cysts Bronchogenic and enteric cysts |

| Esophageal disorders | Achalasia, benign tumors, esophageal carcinoma, esophageal diverticulum |

| Vascular lesions | Aneurysms, hemangioma |

| Miscellaneous | Herniations, pancreatic pseudocyst |

| Paravertebral Lesions | |

| Neurogenic neoplasms | Peripheral nerve neoplasms: Schwannoma, neurofibroma Malignant peripheral nerve sheath neoplasm Sympathetic ganglia neoplasms: Ganglioneuroma, ganglioneuroblastoma, neuroblastoma Paraganglionic neoplasms: Pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma |

| Spinal | Lateral thoracic meningocele Paraspinal abscess (Pott disease) |

| Miscellaneous | Extramedullary hematopoiesis Thoracic duct cysts |

The initial evaluation of patients with mediastinal abnormalities includes a detailed history and physical examination to discover specific symptoms and signs of various mediastinal disorders and associated diseases (Table 71-2). Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiography, computed tomography (CT), and occasionally magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) with CT are used for lesion detection and characterization, usually followed by an invasive procedure for tissue diagnosis. However, some mediastinal lesions have a characteristic radiologic appearance, and biopsy may be unwarranted or contraindicated, as in congenital cysts and vascular lesions, respectively. In addition, laboratory evaluation to include a complete blood count, electrolytes, renal and liver function tests, and serologic tests for various autoantibodies and tumor markers may be useful in the initial evaluation and in posttherapy follow-up.

Table 71-2 Mediastinal Disorders: Constitutional and Paraneoplastic Findings

| Diseases | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Lymphoma | Fever, weight loss, night sweats, pruritus, hypercalcemia |

| Thymoma | Myasthenia gravis, hypogammaglobulinemia, pure red cell aplasia |

| Thymic carcinoid secretion | Cushing syndrome, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone |

| Germ cell neoplasm | Gynecomastia, Klinefelter syndrome, hematologic neoplasms |

| Intrathoracic goiter | Hyper/hypothyroidism |

| Pheochromocytoma | Hypertension, hypercalcemia, polycythemia, Cushing syndrome |

| Autonomic ganglia neoplasm | Opsomyoclonus, hypertension, watery diarrhea, Horner syndrome |

| Sarcoidosis | Hypercalcemia |

Diseases of Anterior Mediastinum

Mediastinal Neoplasms

Thymoma

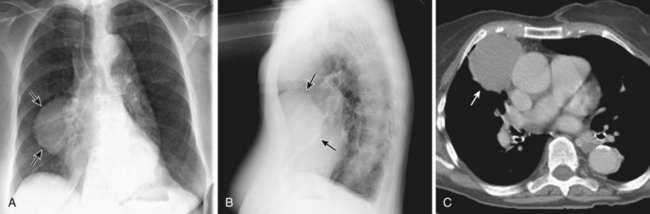

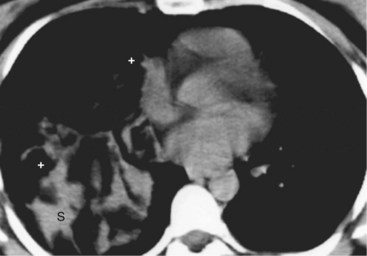

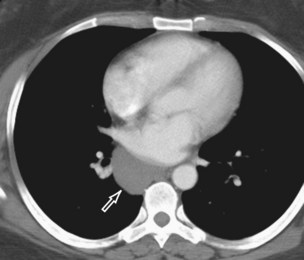

Thymomas manifest on radiography as rounded, well-circumscribed, unilateral, anterior mediastinal masses (Figure 71-2). They are typically located anterior to the aortic root but may be found anywhere from the thoracic inlet to the diaphragm and rarely in the neck. On cross-sectional imaging, thymomas are often homogeneous, soft tissue masses but may exhibit heterogeneity because of cystic change, hemorrhage, or necrosis, especially in large neoplasms. Drop metastases to the ipsilateral pleura, pericardium, or upper abdomen through a diaphragmatic hiatus are well documented and represent invasive disease (Figure 71-3). Pleural drop metastases may encase the lung and mimic diffuse malignant mesothelioma, although associated pleural effusion is infrequent. Lymph node and hematogenous metastases are rare. Mediastinal invasion may be detected with CT and may manifest as an irregular tumoral surface, contralateral extension of thymoma across the midline, and obvious invasion of mediastinal fat and structures. Imaging evidence of local invasion must be correlated with microscopic evidence of capsular transgression and tissue invasion, because encapsulated thymomas may produce fibrous adhesions to adjacent structures. MRI is more sensitive than CT in the detection of vascular invasion. When evaluating a thymic mass, PET-CT may be useful for depicting tumoral invasion, differentiating subgroups of thymic epithelial neoplasms, and staging extent of disease. The maximum standard uptake values (SUVs) of thymoma are typically lower than those of thymic carcinoma. Guided needle biopsy, mediastinotomy, mediastinoscopy, and video-assisted thoracoscopy may establish the diagnosis. However, histologic diagnosis before excisional surgery may not be required in classic cases of thymoma.

Thymic Carcinoma

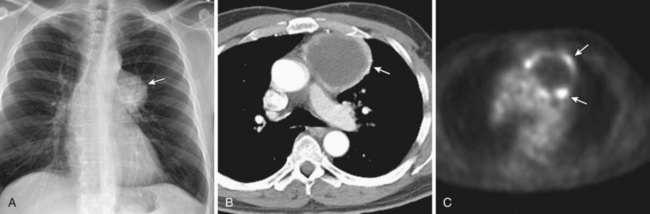

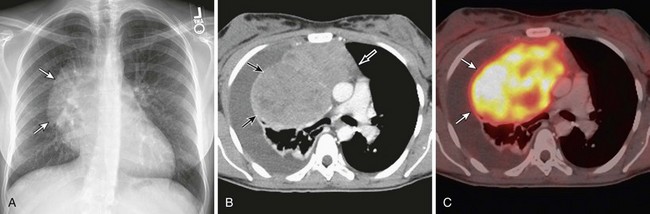

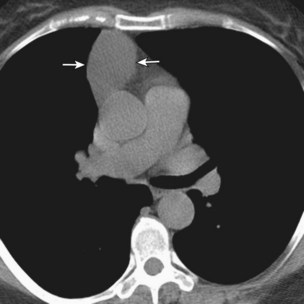

Thymic carcinomas are a heterogeneous group of aggressive epithelial malignancies with a tendency for early local invasion and distant metastases. Men are more often affected (mean age, 46 years). The Revised 2004 WHO classification of thymic epithelial neoplasms describes thymic carcinomas as “nonorganotypic” malignancies (type C) that resemble carcinomas of extrathymic origin, such as lung carcinomas. By traditional histopathologic classification, the two most common cell types are squamous cell and lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma. Unlike thymoma, thymic carcinoma has malignant histologic features and typically manifests as a large, poorly defined, infiltrative, anterior mediastinal mass, frequently with regional lymph node and pulmonary metastases, and pleural and/or pericardial effusions (Figure 71-4).

Thymic Carcinoid

Thymic carcinoid is a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine neoplasm that typically affects men in the fourth and fifth decades of life. These are large, symptomatic, locally invasive neoplasms with frequent distant metastases. Approximately 35% of affected patients develop endocrine abnormalities caused by ectopic hormone production, most often Cushing syndrome. Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type I (MEN-I) may also occur. However, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and the carcinoid syndrome are rare. Radiologically, thymic carcinoid is a large, lobular, heterogeneous, and usually invasive anterior mediastinal mass indistinguishable from thymic carcinoma or thymoma (Figure 71-5). There may be associated intrathoracic metastatic lymphadenopathy. Surgical resection, when feasible, is the treatment of choice, and response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy is poor.

Hodgkin Disease

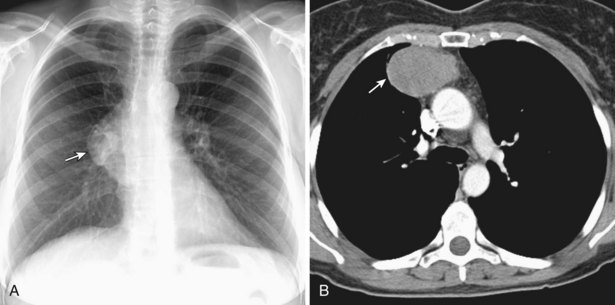

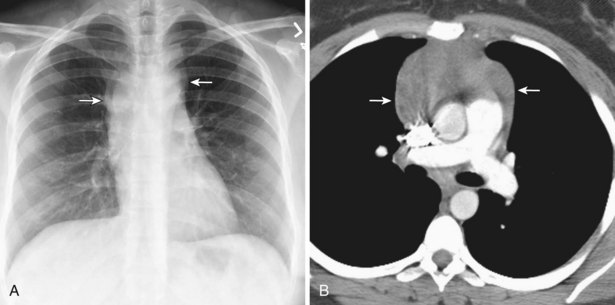

Radiologically, most patients with HD have bilateral, asymmetric, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which frequently involves the prevascular and paratracheal lymph nodes and rarely the posterior mediastinal or juxtacardiac lymph nodes. Nodular sclerosis HD can manifest as a discrete, unilateral anterior mass (Figure 71-6) or bilateral mediastinal mass (Figure 71-7) or as large, lobular, coalescent lymphadenopathy in the anterior mediastinum (Figure 71-8). Invasion, compression, and displacement of mediastinal structures, lung, pleura, and chest wall may occur. Affected lymph nodes usually exhibit homogeneous attenuation but may be heterogeneous because of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic change. De novo lymph node calcification rarely occurs but may develop 1 to 5 years after radiation therapy. Direct invasion of the lung occurs in 8% to 14% of untreated patients and is usually associated with hilar lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis is established with either core biopsy or surgical excision of affected palpable lymph nodes or masses found on imaging.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

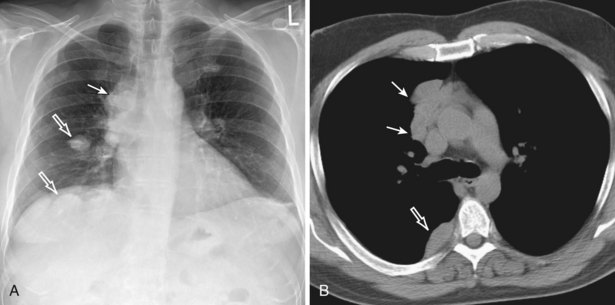

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma typically affects older patients (compared with those affected by HD) and exhibits a slight male predilection. Diffuse, large B-cell and lymphoblastic lymphomas, the most commonly diagnosed subtype in the mediastinum, occur in younger patients. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is more common in women, and lymphoblastic lymphoma is more common in men and is frequently associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Figure 71-9). Both may produce symptoms related to rapid growth and mediastinal invasion, including the superior vena cava syndrome. In addition, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma may manifest as a primary mediastinal mass without extrathoracic lymphadenopathy. Most patients with NHL are initially seen with advanced disease and systemic symptoms, and approximately half have intrathoracic lymph node enlargement. Thoracic lymphadenopathy is typically isolated or noncontiguous and tends to occur in unusual sites, such as the paravertebral, juxtacardiac, and retrocrural lymph node groups (Figure 71-10). Anterior mediastinal involvement is less common than in HD, but imaging features are similar to those of HD.

Mediastinal Teratomas

Teratomas represent the most common mediastinal germ cell neoplasms, accounting for 60% to 70% of cases, and consist of tissues that may be derived from more than one of the embryonic germ cell layers. Most teratomas are well differentiated and benign, thus the term mature teratoma. Uncommon categories include immature teratoma and malignant teratoma or teratocarcinoma. Mature teratoma typically affects children and young adults. Although large tumors may result in symptoms related to local compression, patients with mature teratoma are frequently asymptomatic. Characteristic, but uncommon, symptoms include expectoration of hair (trichoptysis), sebum, or fluid as a result of communication between the tumor and the airways. Radiologically, teratomas are spherical, lobular, well-circumscribed, anterior mediastinal masses that may exhibit calcification on radiography (Figure 71-11). CT typically demonstrates a multilocular cystic mass, and 75% of lesions contain fat attenuation (Figure 71-12). The treatment of choice is surgical excision, and the prognosis is excellent.

Thymolipoma

Thymolipoma is a rare, benign thymic neoplasm composed of mature adipose and thymic tissues. It usually affects young adults and has no gender predilection. Thymolipomas grow slowly, frequently reaching a large size before diagnosis, and almost half of the patients are asymptomatic. Thymolipomas manifest as large, anterior, inferior mediastinal masses that conform to adjacent thoracic structures and may mimic diaphragmatic elevation and cardiac enlargement on radiography (Figure 71-13). These lesions may also exhibit positional changes in shape. CT and MRI demonstrate soft tissue and adipose tissue components and establish an anatomic connection between the lesion and the thymus (Figure 71-14). The treatment of choice is surgical resection. The prognosis is excellent.

Cysts

Thymic Cyst

Thymic cysts are rare anterior mediastinal masses that may be congenital or acquired. Congenital thymic cysts are usually found in the first two decades of life, whereas acquired thymic cysts are seen in association with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or thymic inflammation or malignancy (e.g., carcinoma, HD). Radiologically, thymic cysts are well-defined anterior mediastinal masses with cystic unilocular or multilocular appearances on cross-sectional imaging (Figure 71-15). Surgical excision is the recommended treatment. The diagnosis of cystic neoplasm should always be considered and excluded, and inflammatory cysts must be carefully examined to exclude associated malignancy.

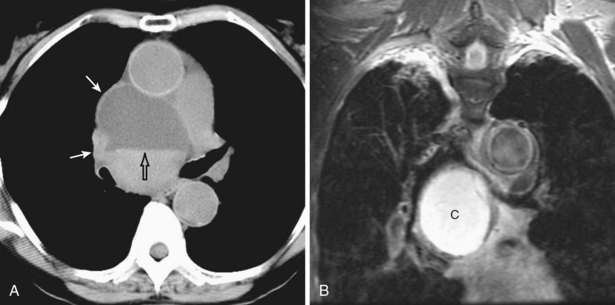

Pericardial Cyst

Pericardial cysts, also termed spring water cysts or clear water cysts because of their clear-fluid contents, are uncommon developmental lesions that occur in the radiographic anterior mediastinum. Most are discovered incidentally in asymptomatic middle-aged adults. These cysts are well circumscribed and usually abut the heart, the diaphragm, and the anterior chest wall, typically in the right cardiophrenic angle. CT typically demonstrates a nonenhancing cystic mass of water attenuation and an imperceptible wall (Figure 71-16). Unless significant symptoms or atypical imaging features are found, pericardial cysts are followed clinically and radiologically.

Glandular Disorders

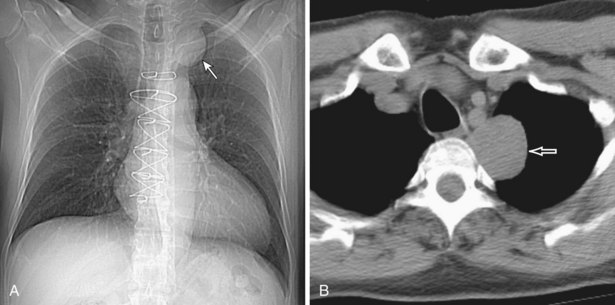

Intrathoracic Goiter

Most intrathoracic goiters result from extension of cervical thyroid goiters into the mediastinum and typically affect women. Although patients are usually asymptomatic, compression of the trachea or esophagus rarely causes symptoms such as dyspnea or dysphagia. The risk of malignant degeneration is small. Most intrathoracic goiters are located in the anterosuperior mediastinum, usually on the right side, but other compartments may be affected. Ectopic intrathoracic goiter without a cervical component rarely occurs. Chest radiography often reveals a cervicothoracic mass that produces mass effect on the trachea. CT demonstrates a lobular, well-defined mass with heterogeneous attenuation resulting from hemorrhage, cystic change, and calcification (Figure 71-17). Intense and sustained contrast enhancement is common. In functioning goiters, uptake of radioactive iodine (iodine 123 [123I] or iodine 131 [131I]) and technetium 99 m (99mTc) pertechnetate is diagnostic. Symptomatic or large goiters may be surgically excised.

Diseases of Middle-Posterior Mediastinum

Lymphadenopathy

Metastatic Mediastinal and Hilar Lymphadenopathy

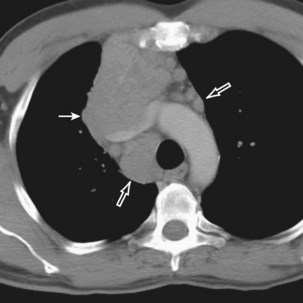

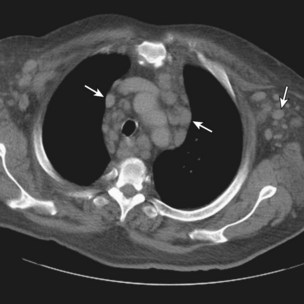

Primary lung, breast, renal cell, gastrointestinal, and prostate carcinomas and malignant melanoma may metastasize to mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes and may manifest as a solitary mass, a dominant mass with lymphadenopathy, or multifocal enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 71-18). Ipsilateral mediastinal metastases from lung carcinoma represent N2 disease and may be operable. The diagnosis of metastases is established by a history of a known primary malignancy and confirmed by biopsy. The treatment depends on the underlying neoplasm and its stage.

Cysts

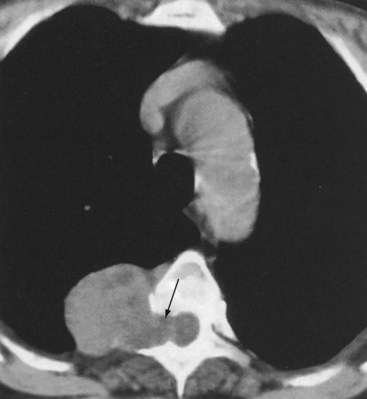

Bronchogenic Cysts

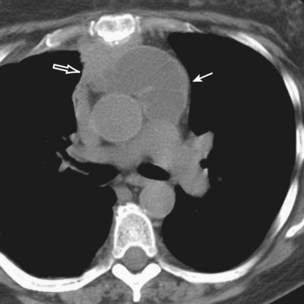

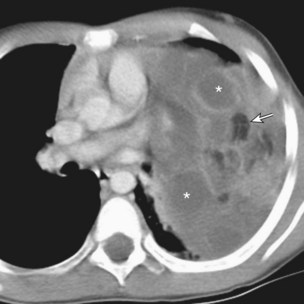

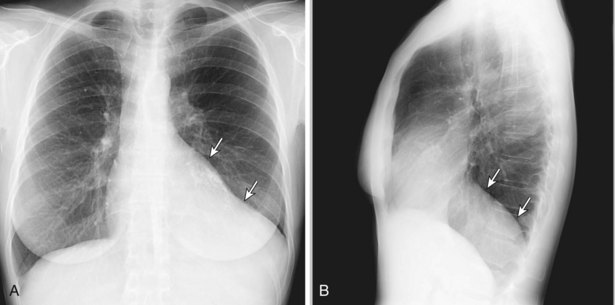

Bronchogenic cysts typically occur in adult men and women but may affect all age groups. Patients are usually asymptomatic, but infection or bleeding eventually produces symptoms in up to two thirds of cases. Radiography usually reveals a well-circumscribed, spherical, middle-posterior mediastinal mass. On CT, these cysts are unilocular homogeneous, nonenhancing masses of variable attenuation, depending on the composition of the fluid (Figures 71-19 and 71-20). The cyst wall may contain calcification or enhance after IV administration of contrast. A gas-fluid level within the cyst is exceptionally rare in mediastinal cysts but frequently occurs in pulmonary cysts and indicates communication with the airways or infection. Large cysts in children may compress the airways, with resultant atelectasis, bronchopneumonia, or air trapping.

Diseases of Paravertebral Compartment

Peripheral Nerve Neoplasms

Schwannoma and Neurofibroma

Radiologically, schwannomas and neurofibromas are sharply marginated, spherical, and occasionally lobular paravertebral masses, which usually span one to two rib interspaces but can attain large sizes (Figure 71-21). Up to one half of the cases cause splaying and benign pressure erosion of the ribs, vertebral bodies, and neural foramina. Approximately 10% of schwannomas and neurofibromas grow through and widen adjacent neural foramina and expand on either end with a “dumbbell” or hourglass configuration (Figure 71-22). Typically, CT reveals a heterogeneous mass that may contain punctate calcification or areas of low attenuation. MRI should always be performed to exclude intraspinal growth of the neoplasm (Figure 71-23). The treatment of choice is surgery. Recurrences are uncommon, even when excision is incomplete.

Sympathetic Ganglia Neoplasms

Ganglioneuromas

Ganglioneuromas are benign neoplasms that affect males and females equally. Affected patients are older children (typically >5 years of age) and young adults. One half of patients are symptomatic from local effects of the tumor or intraspinal growth. Radiologically, ganglioneuromas are well-circumscribed, oblong, paravertebral masses that usually span three to five vertebrae and may exhibit skeletal displacement or pressure erosion (Figure 71-24). MRI is indicated to exclude intraspinal extension. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice and may necessitate a combined thoracic and neurosurgical approach.

Paraganglionic Neoplasms

Pheochromocytoma

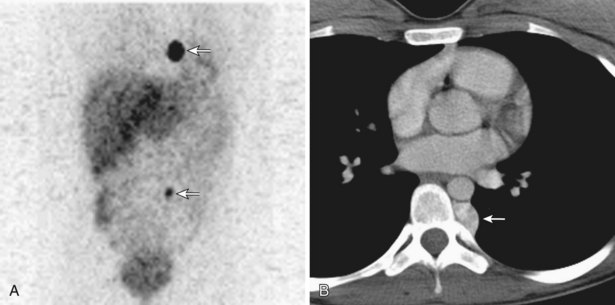

Pheochromocytomas are functioning paragangliomas that most often arise from the adrenal glands and occur more frequently in men in the third to fourth decades. Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas are extraadrenal, and less than 2% are intrathoracic; the latter tend to be more aggressive and multicentric. Symptoms relate to excessive systemic catecholamines or local mass effect. Pheochromocytomas may be part of a multisystem endocrine syndrome (e.g., MEN IIA or IIB). Diagnosis can be established by measurement of urine catecholamines and their metabolites (vanillylmandelic acid, homovanillic acid, metanephrine, normetanephrine). Typically, CT and MRI reveal a well-delineated, enhancing, paravertebral mass. The neoplasm is typically 123I and 123I MIBG avid (Figure 71-25). Treatment includes sympathetic α- and β-blockade for 1 to 2 weeks, followed by surgical excision. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be used to treat metastatic disease.

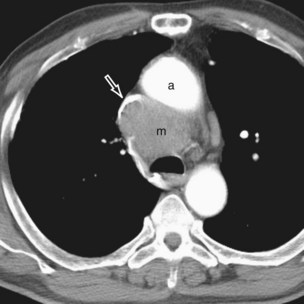

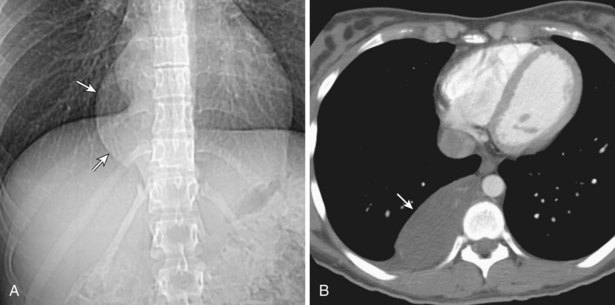

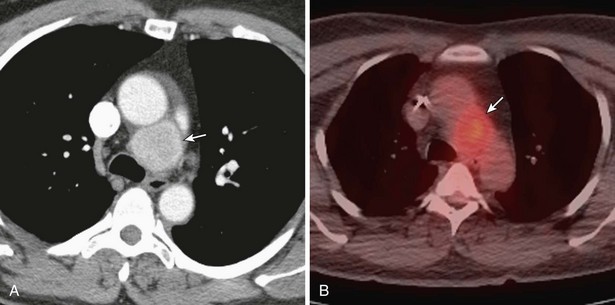

Paraganglioma

Paragangliomas are rare neoplasms of paraganglionic tissue. Most are benign, asymptomatic, and nonfunctioning. Radiologically, they typically manifest as sharply marginated, middle-posterior mediastinal nodules or masses, usually located adjacent to the aorta, pulmonary arteries, heart, or costovertebral sulci or within the left atrial wall (Figure 71-26). Paragangliomas are hypervascular lesions and demonstrate marked contrast enhancement. The treatment is surgical excision.

Spinal Lesion

Lateral Thoracic Meningocele

Lateral thoracic meningoceles are rare and consist of redundant meninges that protrude through the neural foramen and contain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These meningoceles do not exhibit a gender predilection and typically occur in association with neurofibromatosis. Patients are usually asymptomatic adults in the fourth to fifth decades. Radiologic studies demonstrate a well-circumscribed, paravertebral, cystic lesion, frequently associated with vertebral erosion, kyphoscoliosis, and/or widening of adjacent neural foramina (Figure 71-27). Cross-sectional imaging may demonstrate continuity with the thecal sac. CT demonstrates a homogeneous nonenhancing mass of water attenuation, and MRI shows signal intensity equal to that of adjacent CSF. Symptomatic lateral thoracic meningoceles are treated with surgical excision.

Boiselle PM, Rosado-de-Christenson ML. Fat attenuation lesions of the mediastinum (pictorial essay). J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;26:881–889.

Cronin CG, Swords R, Truong MT, et al. Clinical utility of PET/CT in lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:W91–W103.

Henschke CI, Lee IJ, Wu N, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: prevalence and incidence of mediastinal masses. Radiology. 2006;239:586–590.

Kim JH, Goo JM, Lee JJ, Chung MJ, et al. Cystic tumors of the anterior mediastinum: radiologic-pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:714–723.

Kumar A, Regmi SK, Dutta R, et al. Characterization of thymic masses using (18)F-FDG-PET-CT. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:569–577.

Rankin S. [(18)F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET/CT in mediastinal masses. Cancer Imaging. 2010;10(spec A):156–160.

Shepard JO, Maher MM. Imaging of thymoma. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;17:12–19.

Takahashi K, Al-Janabi NJ. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32:1325–1339.

Tanaka O, Kiryu T, Hirose Y, et al. Neurogenic tumors of the mediastinum and chest wall: MR imaging appearance. J Thorac Imaging. 2005;20:316–320.

Tateishi U, Muller NL, Johkoh T, et al. Primary mediastinal lymphoma: characteristic features of various histologic subtypes on CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:782–789.

Tian L, Liu LZ, Cui CY, et al. CT findings of primary non-teratomatous germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: a report of 15 cases. Eur J Radiol. 2011. [Epub ahead of print]