32 Disorders of the Eye

Abnormal Red Light Reflex

Cataracts

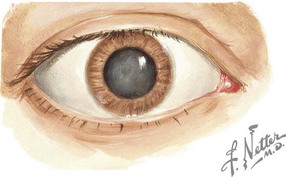

Congenital cataracts occur in two in 10,000 births (Figure 32-1). Of these, 20% to 25% of cases occur secondary to a congenital infection (rubella, cytomegalovirus, or toxoplasmosis) or as a component of a genetic or metabolic condition, such as Turner syndrome, Down syndrome, trisomy 13 and 18, galactosemia, and peroxisomal disorders. Children exposed to high-dose long-term corticosteroid therapy are also at risk, as are children with uveitis or who sustain ocular trauma.

Disorders of Eye Movement

Strabismus

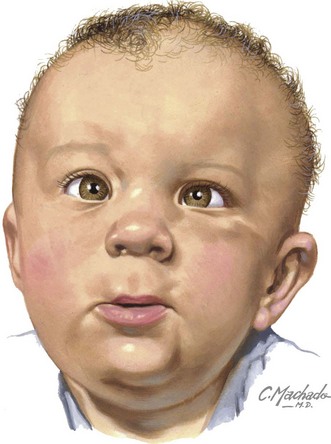

Misalignment of the eyes affects approximately 4% of children younger than 6 years of age (Figure 32-2). Heterophoria is the intermittent tendency for eyes to deviate, and heterotropia is a constant misalignment. The prefixes eso- (inward), exo- (outward), hyper- (upward), and hypo- (downward) indicate the direction of the misaligned eye. Other causes of eye deviations are cranial nerve palsies, intracranial or intraorbital mass, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), and myasthenia gravis.

Red Eye

Viral Conjunctivitis

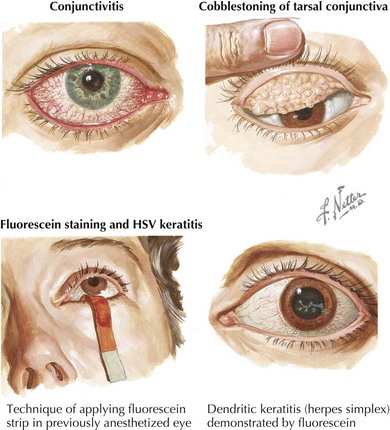

Viral conjunctivitis presents with watery or mucopurulent discharge, eye irritation, and scleral injection (Figure 32-3). Both eyes are usually affected simultaneously or in sequence. More serious infection causes pseudomembranes (inflammatory debris and fibrin) or true conjunctival membranes. Punctate keratitis and subepithelial opacities may also occur, causing decreased vision, photosensitivity, or glare and haloes around bright lights.

Other agents such as measles (rare because of widespread immunization), influenza, enterovirus, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) can cause conjunctivitis. Primary or recurrent HSV can also cause keratitis (corneal inflammation) with a dendrite pattern seen on fluorescein staining (see Figure 32-3). Treatment of ocular HSV includes topical antivirals (trifluridine, vidarabine, or iododeoxyuridine) and, depending on the extent of infection, oral or intravenous acyclovir. Consultation with an ophthalmologist is recommended.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Practitioners should suspect Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis infection when symptoms of conjunctivitis are present in an infant in the first 2 weeks of life, termed ophthalmia neonatorum (see Chapter 105 for a detailed discussion).

Allergic Conjunctivitis

The hallmark of allergic conjunctivitis is itching along with clear tearing, injected conjunctivae, and conjunctival edema (chemosis) in both eyes. In more severe cases, cobblestoning of the tarsal conjunctivae is present (see Figure 32-3). Allergic conjunctivitis occurs as a seasonal disorder accompanied by allergic rhinitis or can occur perennially if associated with allergens such as cat dander, dust mites, mold spores, and other environmental allergens. Elimination of the offending agent and symptomatic treatment with cold compresses is recommended. Topical therapy with mast cell stabilizers or antihistamines can be used, as can oral antihistamines. More severe cases may require referral to an allergist, who may prescribe topical corticosteroids or immunotherapy.

Disorders of Adnexal Structures

Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

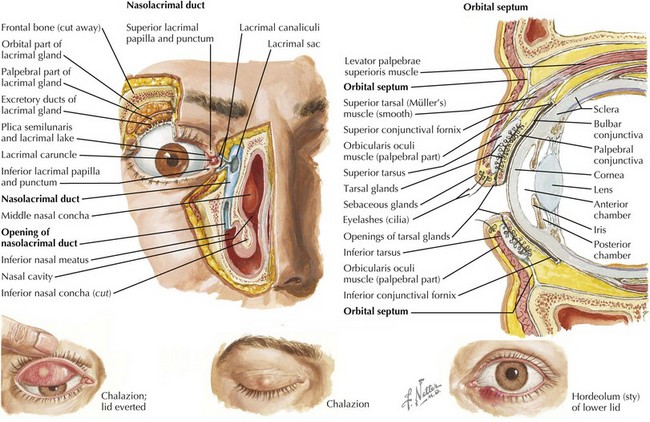

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction occurs in 2% to 4% of full-term babies and is even more common in premature babies. Congenital obstruction is usually caused by an imperforate membrane at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct (Figure 32-4). Patients present with tears overflowing the eyelid (epiphora) and mucoid matter crusting the eyelashes.

Hordeolum and Chalazion

A hordeolum is inflammation or impaction of a sebaceous gland of the eyelid. Whereas an internal hordeolum involves the meibomian glands and occurs on the conjunctival surface, infection of the glands of Zeiss or Moll causes an abscess on the eyelid margin known as an external hordeolum (stye). A chalazion is a chronic granulomatous inflammation of a meibomian gland, which is noted as a small, rubbery nodule located more centrally on the eyelid (see Figure 32-4).

Preseptal (Periorbital) Cellulitis

Preseptal cellulitis is inflammation of the eyelids and periorbital tissues anterior to the orbital septum (see Figure 32-4), usually caused by contiguous infection of the periorbital soft tissues of the face. The most common pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus, group A β-hemolytic streptococcus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Patients present with erythema and swelling of the eyelids and conjunctival injection but will not have proptosis or limited ocular movements as in orbital cellulitis (see below).

Ocular Trauma

Corneal Abrasion

Corneal abrasion presents with the sensation of a foreign body in the eye, pain, scleral injection, tearing, and photophobia. Pediatricians can detect corneal epithelial defects with fluorescein dye (see Figure 32-3). The eyelid should be everted to check for retained foreign body. Vision testing should also be performed, and if vision changes are present, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist. Topical antibiotic ointment is prescribed for infection prophylaxis and lubrication of the eye. Patients who wear contact lenses should be treated with topical fluoroquinolones for Pseudomonas spp. Without treatment, an infection could progress to a corneal ulcer. Oral analgesics can be used for pain. Topical anesthetics are no longer recommended because they slow epithelial healing and decrease the protective blinking reflex.

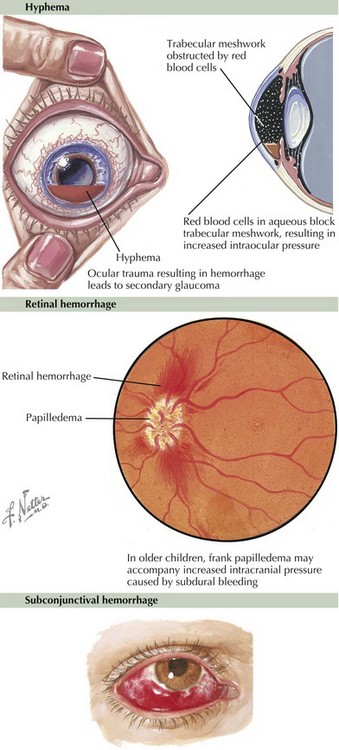

Hyphema

Hyphema is blood in the anterior chamber that is usually caused by blunt injury. Layering of blood cells can be seen by penlight or slit lamp (Figure 32-5). Increased ocular pressure may develop if the trabecular meshwork is affected either by the original injury or by red blood cells causing a blockage. Patients are at risk for rebleeding 3 to 5 days later. Patients with sickle cell disease or trait are at higher risk for complications and require more aggressive intervention.

Retinal Hemorrhage

Retinal hemorrhages can be caused by increased intrathoracic pressure or by acceleration–deceleration injuries. They are common in newborns delivered vaginally and resolve within 2 to 6 weeks without sequelae. They can also occur during trauma and are present in 85% of cases of shaken babies. The hemorrhages seen in non-accidental trauma have a distinctive pattern and are often bilateral, flame-shaped, and include preretinal structures and the macula (see Figure 32-5).

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is the presence of blood between the conjunctiva and sclera (see Figure 32-5), is extremely common in newborns after vaginal birth, and resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks. In older children and adults, these hemorrhages are usually caused by increased intraocular pressure from coughing or sneezing or result from infection such as adenoviral conjunctivitis. Patients should be carefully examined to rule out a perforating injury.

American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology And Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association of Certified Orthoptists. Red reflex examination in neonates, infants, and children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1401-1404.

Binenbaum G, Mirz-George N, Christian CW, Forbes BJ. Odds of abuse associated with retinal hemorrhages in children suspected of child abuse. J AAPOS. 2009;13(3):268-272.

Blaivas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. A study of bedside ocular ultrasonography in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(8):791-799.

Daoud YJ, Hutchinson A, Wallace DK, Song J, Kim T. Refractive surgery in children: treatment options, outcomes, and controversies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):573-582.

Pieramici DJ, Goldberg MF, Melia M, et al. A phase III, mulitcenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of topical aminocaproic acid (Caprogel) in the management of traumatic hyphema. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(11):2106-2112.

Togioka BM, Arnold MA, Bathurst MA, et al. Retinal hemorrhages and shaken baby syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Emerg Med. 2009;37(1):98-106.