20 Disorders of the eye

Clinical assessment of the eye

Most eye disorders can be diagnosed by history and examination; special investigations are rarely necessary. Causes of eye symptoms are summarised in Table 20.1.

| Nature | Type | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Pain |

Examination

The important features of eye examination are shown in Table 20.2.

| Property examined | Tests and abnormal findings |

|---|---|

| Visual acuity (normal = 6/6) |

Visual fields

The rules of interpretation of acuity and field tests are:

• lesions anterior to the chiasma affect one eye only

• lesions at the chiasma usually damage the crossing nasal fibres from each eye to give rise to bitemporal field defects

• lesions posterior to the chiasma damage the temporal fibres from one eye plus the nasal fibres from the other eye, causing a homonymous defect.

Pupils

Abnormal pupillary responses are summarised in Table 20.3. The light reflex (parasympathetic) is intact when a light shone on one eye constricts both pupils at an equal rate and to a similar degree.

| Abnormality | Common causes |

|---|---|

| Dilatation |

The red eye

The features of the dangerous red eye are shown in Box 20.2 and urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is required if these are present.

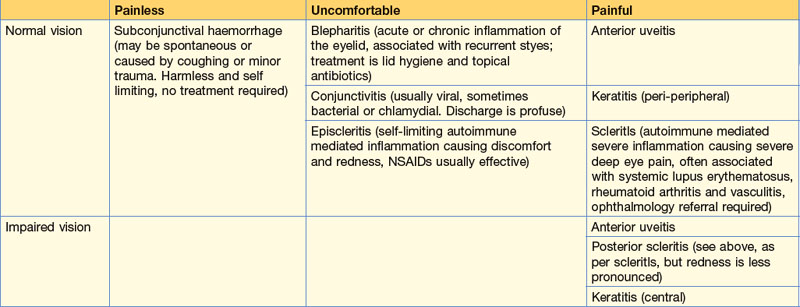

The presence or absence of pain helps narrow down the possible causes of the red eye (Table 20.4).

The painful eye

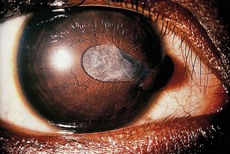

Acute anterior uveitis (inflammation of the iris and/or ciliary body) may be associated with systemic disorders, for example HLA B27-positive arthropathies and sarcoidosis. Pain is usually moderate. Redness is most marked around the cornea (Fig. 20.1). Specialist attention is required from an ophthalmologist.

Ophthalmic injuries

Penetrating injuries

Penetrating injuries may be suspected when there is decreased visual acuity, a soft eye and a distorted iris (tear-drop shaped pupil, Fig. 20.2).

Visual loss

Acute loss of vision

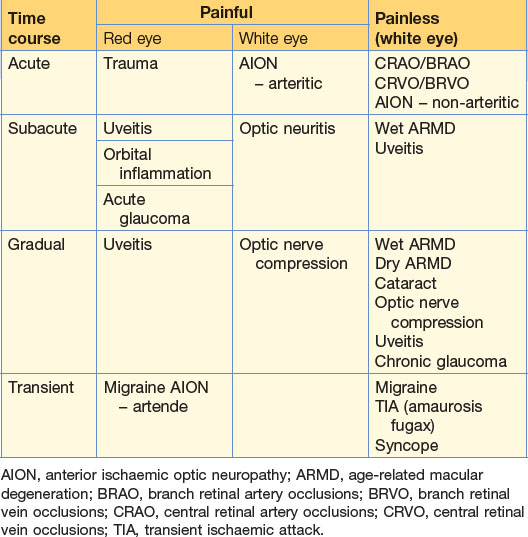

The causes of visual loss are shown in Table 20.5. They may be acute, subacute or gradual, and either partial or total. Unilateral symptoms are likely to be from lesions of the eye or optic nerve. Bilateral lesions result from defects proximal to the optic chiasma in the brain.

Retinal artery occlusion

This occurs in the optic nerve, just behind the visible optic nerve head, usually as a result of a thrombosis of atheromatous vessels. Branch retinal artery occlusions are usually embolic, derived from atheroma from the carotid arteries. Emboli may be visualised on fundoscopy as white or yellow particles lodged in the bifurcations of the retinal arterioles. When the central retinal artery is involved, the visual loss is sudden and painless and the deficit profound. At fundoscopy, there is a pale retina with attenuated vessels and a cherry spot at the macula (Fig. 20.3). There is an impaired direct light response. Branch retinal artery occlusion affects vision, depending on the location of the vessel and a visual field defect (scotoma) results.

Management of acute visual loss

If the nature of the visual loss suggests amaurosis fugax (transient clouding over of vision in one eye, typically like a curtain descending) a carotid duplex scan is indicated to look for carotid artery stenosis (see p. 215).

Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is usually spontaneous but may be traumatic. It causes a visual field loss which may be small, and visual acuity is retained unless the macula is involved. If the detachment is small, fundoscopy may be normal. The detachment is seen as an elevated convex area of grey retina which moves with ocular movement and has a wrinkled surface (Fig. 20.4). Treatment aims to oppose the detached retinal and underlying retinal pigment epithelium using laser or cryoprobe.