107 Disorders of the Esophagus

Developmental Anomalies

Etiology and Pathogenesis

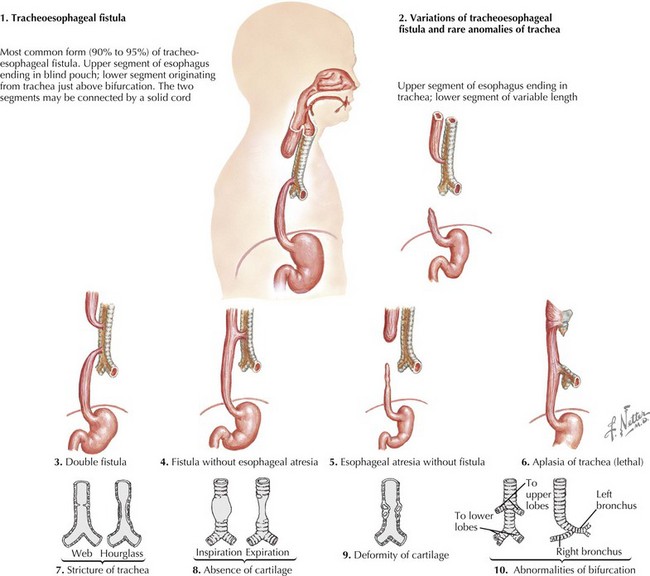

The esophagus forms from a small ventral diverticulum of the embryonic foregut. This diverticulum separates into the esophagus and trachea around the fourth gestational week of fetal development. Anomalies can occur with abnormalities in any step in esophageal formation and development. One of the most common anomalies is TEF with or without atresia. This occurs when there is a disruption in the elongation and separation of the trachea from the esophagus. There are five types of TEF. The most common is type C in which there is atresia of the proximal esophagus with a fistula from the trachea to the distal esophagus (Figure 107-1). Other categories of TEF, in descending frequency, include isolated esophageal atresia without TEF, isolated TEF, esophageal atresia with proximal TEF, and esophageal atresia with proximal and distal TEF.

Motility Disorders of The Esophagus

Evaluation

Achalasia

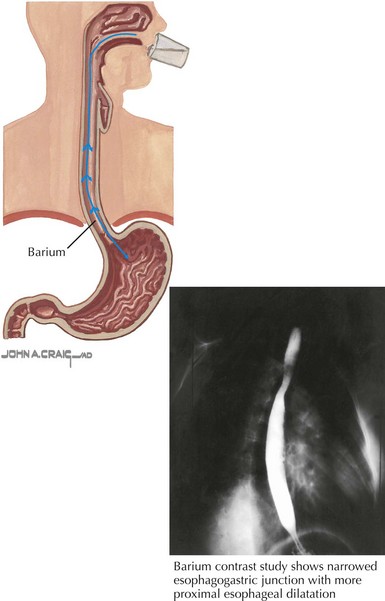

Chest radiograph may show widening of the mediastinum, loss of the gastric air bubble, or an esophageal air-fluid level. Barium swallow will show impaired contrast movement, abnormal peristalsis, and tapering of the distal esophagus known as the “bird’s beak” sign (Figure 107-2). Endoscopy should always be performed and often shows esophageal dilatation, erythema, and ulceration from stasis. Esophageal manometry assesses LES pressures and function in addition to esophageal contraction and motor pattern. In achalasia, manometry shows increased lower esophageal pressure, abnormal peristalsis, and elevated intraesophageal pressures.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of GERD can most often be made clinically with a thorough medical and dietary history and a physical examination. Diagnostic studies should be reserved for those with atypical or concerning symptoms (Box 107-1), symptoms unresponsive to therapy, or symptoms suggestive of anatomic abnormality or tissue damage (hematemesis, bloody stool, anemia). An upper GI study with barium swallow is used to demonstrate anatomic anomalies. Scintigraphy (also known as milk scan or gastric emptying study) can show delayed gastric emptying. Upper endoscopy assesses for mucosal injury, inflammation, or dysplasia and may distinguish GERD from eosinophilic esophagitis. Esophageal pH monitoring is helpful to evaluate the frequency of acid reflux events, and multichannel intraluminal impedance studies can demonstrate non–acid reflux events. These measurements are also correlated with symptoms to help establish or refute the relationship between clinical symptoms and GERD.

Management

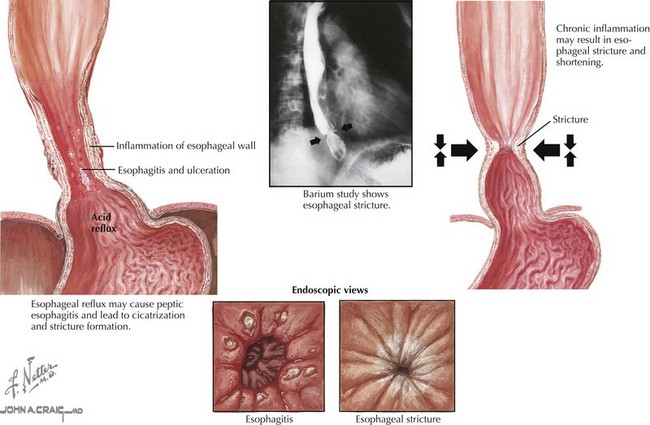

The goals of treatment of GERD are to reduce symptoms; heal esophageal mucosal injury; and prevent complications, including esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus (metaplasia of the lower esophagus), and stricture formation (Figure 107-3). In infants with GER who are not bothered by emesis and who are growing appropriately, no therapy is necessary. Initial therapy for symptomatic infants with GERD is lifestyle modification, including thickening of feeds, giving smaller volume frequent feeds, frequent burping, and maintaining upright position for longer duration after feeds. Pharmacologic therapy for GERD includes antacids to buffer existing acid and H2 receptor antagonists (e.g., ranitidine) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; e.g., omeprazole) to decrease secretion of acid from parietal cells. PPIs have been shown to be the most effective pharmacologic therapy for GERD. However, they are not always necessary and may be associated with adverse effects such as an increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia and acute gastroenteritis. Prokinetic use (e.g., metoclopramide) has declined because of unfavorable side effect profiles. Surgical fundoplication, a procedure in which the fundus is wrapped around the distal esophagus, is an option for children who are unresponsive to pharmacologic treatment and for those who develop respiratory compromise or stricture. Side effects of fundoplication are not inconsequential and include bloating, dysphagia, dumping syndrome, hernia, small bowel obstruction, and recurrence requiring a second fundoplication.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Evaluation

Endoscopy with biopsy is the main diagnostic modality for esophagitis. Macroscopic visualization of the esophagus may reveal erythema, erosions, or ulcerations; however, a normal macroscopic appearance of the esophagus does not exclude histologic esophagitis. Histology, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry can help distinguish the different causes of esophagitis (Table 107-1).

Table 107-1 Characteristic Histological Findings for Various Causes of Esophagitis

| Finding | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Eosinophils | |

| <20/hpf >20/hpf |

Primary GER Idiopathic EoE |

| Macroscopic shallow ulcers Mononuclear infiltrate Multinucleate giant cells |

Herpes simplex esophagitis |

| Basophilic nuclear inclusions | Cytomegalovirus esophagitis |

| Macroscopic white plaques Pseudohyphae and budding yeast |

Candidal esophagitis |

| Polymorphonuclear infiltrate, vessel thrombosis, granulation tissue | Corrosive esophagitis |

EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; GER, gastroesophageal reflux; hpf, high-power field.

Traumatic Injuries to the Esophagus

Hassall E. Step-up and step-down approaches to treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:324-331.

Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: a pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:150-154.

Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines. Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498-547.

Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(1):30-36.

Wilsey MJJr, Scheimann AO, Gilger MA. The role of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of caustic ingestion, esophageal strictures, and achalasia in children. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clin North Am. 2001;11(4):767-787.