Chapter 25. Disorders of the ankle and foot

Ankle

Osteoarthritis of the ankle

Osteoarthritis of the ankle can follow any damage to the joint. The damage may be a single injury such as a fracture, repeated minor trauma, or any other insult to the joint, including infection.

Clinical features

As the degeneration proceeds, osteophytes form on the neck of the talus and obstruct joint movement. Dorsiflexion is usually the first to be affected. The patient gradually becomes aware that they cannot walk comfortably barefoot. This is because the heel of the shoe allows the ankle to be held in slight flexion.

Later, as the osteophytes on the neck of the talus and the anterior lip of the tibia enlarge, the ankle becomes progressively stiffer and it becomes painful to walk, even in normal shoes. At this point the patient will usually seek advice.

Footballer’s ankle

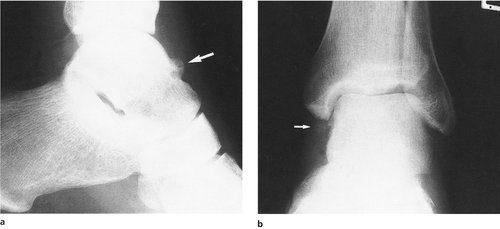

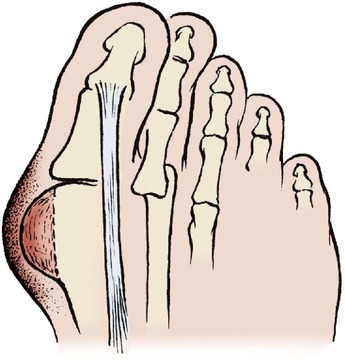

Footballer’s ankle occurs in habitual footballers and is caused by repeated strains of the anterior capsule (Fig. 25.1). Bone gradually builds up at each end of the anterior capsular fibres, producing osteophytes which restrict movement. The condition is indistinguishable from early osteoarthritis.

|

| Fig. 25.1

(a), (b) ‘Footballer’s ankle’. Early osteoarthritic change with osteophytes and new bone formation ( arrowed).

|

Conservative treatment

There are three forms of conservative treatment:

1. A raise to the heel of the shoe will take pressure off the anterior osteophytes.

2. A normal working boot may reduce the angular forces at the ankle.

3. Anti-inflammatory drugs.

Operative treatment

Operative treatment is seldom required but three procedures are available:

1. Excision of osteophytes and arthroscopic debridement.

2. Arthrodesis.

3. Joint replacement.

Excision of osteophytes from the neck of the talus and the anterior margin of the tibia will improve extension and may relieve symptoms for many years, particularly in footballer’s ankle, but recurrence is likely if the patient continues to play.

Arthrodesis. If pain is severe, arthrodesis may be needed. Arthrodesis of the ankle only abolishes flexion and extension. Inversion and eversion, which occur at the subtalar joint, and supination and pronation, which occur at the midtarsal joint, are unaffected. Rehabilitation after arthrodesis of the ankle is slow, and patients should be warned that it takes 2 years to achieve the final result.

The ankle is usually arthrodesed in slight flexion to accommodate the heel of a normal shoe, although this makes it difficult to walk barefoot. The operation is unsuitable for women who wish to wear heels of a varying height.

Joint replacement is possible, but unsuccessful with present prostheses.

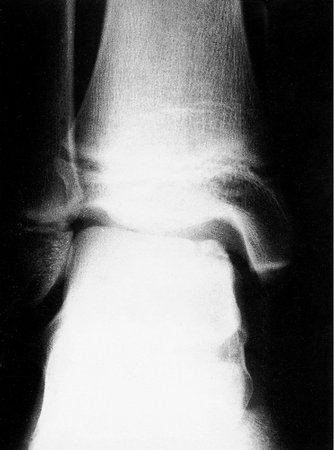

Osteochondritis dissecans and osteochondral fractures

A small fragment of talus may separate from the body as a loose fragment by a similar process to that seen at the knee (p. 326). Osteochondral fractures of the talus also occur (Fig. 25.2).

|

| Fig. 25.2

Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus.

|

Treatment

If the loose bodies are painful or cause mechanical symptoms then they need to be removed, either arthroscopically or by arthrotomy.

Aseptic necrosis

Aseptic necrosis of the body of the talus may follow fractures through its neck (p. 276). The end result is a loss of height of the talus and a stiff ankle. Left untreated the ankle becomes progressively stiffer but usually becomes painless after a few years. Arthrodesis is not possible because the bone on the talar side of the ankle is dead. Prosthetic replacement is not possible and the disability has to be accepted.

Treatment

There is no active treatment for this condition apart from analgesics and a firm boot to support the ankle.

Rheumatoid arthritis

The bone destruction of rheumatoid arthritis produces a foot and ankle that are unstable as well as painful. Because bone is lost, the ligaments no longer hold the bones in the correct position, the foot rolls into valgus at the subtalar joint and the forces at the ankle produce wear on the lateral side. This in turn leads to a valgus deformity.

Treatment

The unstable valgus ankle of rheumatoid is difficult to manage. Conservative treatment should always be tried before operation. The following measures may help:

1. Ankle supports or surgical footwear to control the deformity, but these are often ineffective.

2. Arthrodesis, which is usually effective despite the poor bone texture.

3. Total ankle replacement, which is less reliable than joint replacement elsewhere.

4. Osteotomy to correct the alignment of the foot and ankle, but the deformity can recur.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the ankle generally have other joints involved as well and the whole problem must be considered.

Ligamentous instability

Damage to the ligaments of the ankle from sprains may make the ankle liable to recurrent episodes of minor instability. The patient may complain that he or she keeps ‘turning the ankle over’ with trivial injury, but clinical and radiological examination are normal. Stress radiographs will demonstrate the opening of the joint and from this pattern the ligaments involved can be deduced.

The lateral collateral ligament, and in particular the anterior talar fibular ligament, is the most common site of injury but the anterior capsule can also be involved.

Treatment

The symptoms can often be relieved by exercises to improve the postural reflexes and strengthen the postural muscles around the ankle. If this is ineffective, operation may be needed to reinforce the lateral side of the ankle by rerouting the peroneus brevis tendon or by a free graft of plantaris. Direct suture methods and shortening of the lateral ligaments can give good results.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome

The medial plantar nerve enters the foot after passing beneath the medial ligament of the ankle, which it shares with the posterior tibial and flexor tendons. The anatomy is comparable with the carpal tunnel at the wrist and the medial plantar nerve is vulnerable to compression by swelling of the tendons or space-occupying lesions such as ganglia. The symptoms of ‘tarsal tunnel syndrome’ include pain and paraesthesia in the distribution of the medial plantar nerve.

Treatment

Decompression of the tunnel is needed only if there is definite proof by electrical studies that the nerve is compressed within the tunnel.

Foot

Subtalar joint

The subtalar joint allows inversion and eversion. Damage to the talus or fractures of the calcaneum can restrict eversion and inversion and make it difficult or painful to walk over rough ground.

Injuries to the subtalar joint commonly result from a fracture of the calcaneum in a fall onto the heel, a common injury in building workers. Ironically, these are the very people who need a good subtalar joint to walk over rough ground.

Treatment

Injuries to the subtalar joint can take at least 2 years to reach their final state and any decision on operation should be deferred until this time has been reached. Until then, support to the ankle and subtalar joint with a firm boot to restrict inversion and eversion will produce some relief and may allow the patient to walk over rough ground.

If the joint is still painful after 2 years, subtalar fusion may be required. Like ankle arthrodesis, it may take 2 years to achieve the final result.

Midtarsal joint

The midtarsal joint lies between the calcaneum proximally and the cuboid and navicular bones distally and, with the tarsometatarsal joint, allows pronation and supination of the forefoot on the hindfoot. Because the subtalar, midtarsal and tarsometatarsal joints are so closely connected, damage to one can impair the function of the other two.

The joint can be damaged by trauma (p. 278), talipes equinovarus (p. 352) and other foot deformities. The result is painful restriction of movement in the foot, detectable on clinical examination (p. 31).

Treatment

Conservative treatment with a firm shoe or boot is often effective, but if pain or deformity cannot be controlled, a triple fusion may be required.

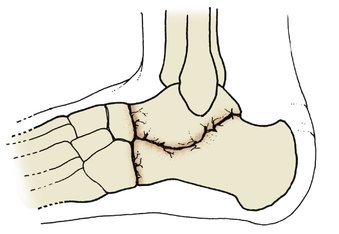

Triple fusion is an arthrodesis of all three joints (talonavicular, calcaneocuboid and subtalar) and converts the tarsus into a solid block of bone (Fig. 25.3). Ankle movement and midtarsal movements are not affected, but inversion and eversion are abolished. The operation is often used as the definitive treatment for the residual deformity of talipes when the patient has reached adult life.

|

| Fig. 25.3

Triple fusion. Three joints are fused – calcaneocuboid, talonavicular and subtalar.

|

Pantalar arthrodesis. If the triple fusion is accompanied by an ankle arthrodesis, the operation is known as a pantalar arthrodesis and may be required if the talus has been damaged by trauma or avascular necrosis.

Köhler’s disease

Köhler’s disease is a vascular osteochondritis which causes collapse of the navicular and is comparable with Perthes’ disease at the hip and Kienböck’s disease at the wrist. The joint becomes painful and the affected bone is tender. Radiographs show that the bone becomes dense, collapses and gradually reforms over a period of 2–3 years. The shape of the reformed bone is different from the original, but frequently produces an excellent functional result.

Treatment

No treatment is required.

Sever’s disease

Sever’s disease is a traction apophysitis at the insertion of the Achilles tendon comparable with Osgood–Schlatter’s and Sinding Larsen’s diseases at the knee. The condition occurs most often in boys about the age of 12 and causes pain and tenderness at the insertion of the Achilles tendon onto the calcaneum.

Treatment

The symptoms usually resolve within 12 months and no treatment is required apart from a slight raise to the heel of the shoe to take tension off the Achilles tendon.

Achilles tendinitis and paratenonitis

The paratenon around the Achilles tendon may be irritated by repeated friction. The condition is common in athletes.

Treatment

If rest, a raise to the heel and attention to athletic technique do not help, a steroid injection into the space between the tendon and paratenon – but not into the tendon itself – may be helpful.

In very resistant cases the paratenon will need to be freed from the tendon surgically.

Partial rupture of the Achilles tendon

The central fibres of the Achilles tendon sometimes rupture without breaking the continuity of the tendon. In such patients, the ‘squeeze’ test (p. 276) is negative and the tendon will have a tender, fusiform swelling in its midportion.

Treatment

The symptoms usually resolve over 12–18 months and a raise to the heel is helpful. If the symptoms persist after this time, the tendon may need to be explored. A cyst or softened area of tendon will often be found in the centre of the tendon corresponding to the site of the rupture of the original central fibres.

Flexor and peroneal tendonitis

The peroneal and flexor tendons have flexor sheaths and are sometimes affected by tenosynovitis where the tendons run round the corner from the calf into the foot, particularly if there has been trauma to the ankle or subtalar joints.

Treatment

Anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injection into the tendon sheaths are usually effective.

Recurrent subluxation of the peroneal tendons

The peroneal tendons run in a shallow groove behind the lateral malleolus and may become unstable. If this occurs, the tendons will flick out of their groove and lie in front of the malleolus. The ankle feels unstable and the patient may stumble.

Treatment

Conservative treatment is rarely effective. If the symptoms warrant it the tendons should be stabilized by a bone block to deepen the groove in which they run.

Plantar fasciitis

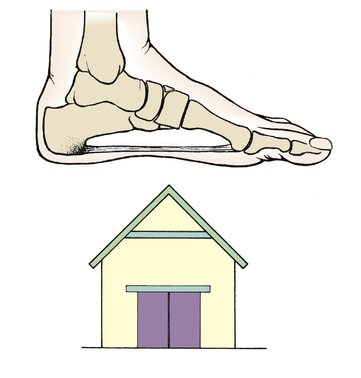

Plantar fasciitis is a common and troublesome condition caused by a strain of the attachment of the plantar fascia to the calcaneum, and causes pain when the patient puts the foot to the ground when walking (Fig. 25.4).

|

| Fig. 25.4

Plantar fasciitis. The plantar fascia supports the medial arch of the foot like a tie-bar and its posterior attachment may be painful.

|

Clinical examination will show a very tender spot at its calcaneal insertion and radiographs may show a spur of bone at the same site but no other abnormality (Fig. 25.5).

|

| Fig. 25.5

A plantar spur.

|

Treatment

A small heel raise and a pad worn in the shoe will usually relieve symptoms if the pad is firm and not too soft. Physiotherapy with stretching of the Achilles and the plantar fascia is the treatment of choice. Steroid injection is often advised, but is always painful and often ineffective. Excision of the heel spur seen on the radiographs is tempting but not generally successful. (Remember that 10% of the normal population have a spur visible on X-ray and of these, only 10% are symptomatic.)

‘Heel bumps’

Heel bumps (Haglund’s deformity) or exostoses occur just lateral to the Achilles tendon and cause particular worry to teenagers, in whom they interfere with shoe wear.

The bumps appear about the age of 11 and usually stop hurting when growth is complete.

Treatment

If the bumps are particularly large and painful, they need to be excised, but this is a troublesome operation. The excision must include the underlying bony lump and the resulting scar and soft tissue swelling may be almost as troublesome as the original bump. Calcaneal osteotomy is an alternative.

Talonavicular bar

The talus, navicular and the other tarsal bones are occasionally linked by a bar of bone. These bars, which are congenital anomalies, prevent all subtalar movement and cause pain when the foot is twisted.

In some patients, the ‘bar’ is of fibrous tissue instead of bone and some movement is then possible, although still abnormal.

Treatment

The symptoms usually subside as growth proceeds and can be controlled by supportive footwear. In a very few cases, the bar will need to be excised.

Ganglia

The joints on the dorsum of the foot are superficial and, as on the back of the hand, ganglia can cause troublesome symptoms. Before making the diagnosis be sure that the swelling is not the muscle belly of the extensor hallucis brevis, which can look very like a ganglion, lipoma or a soft tissue tumour.

Treatment

Excision is only needed if the ganglion is persistent, tender and painful. As in the hand, the scar and postoperative swelling may be as much trouble as the original ganglion. Pain may last for 6 months after operation.

Dorsal exostosis

The dorsum of the foot is a common site for an exostosis, particularly at the junction of the navicular and cuneiform bones. The swelling interferes with shoe wear and a bursa may develop over it.

Treatment

If the swelling is troublesome then it should be excised.

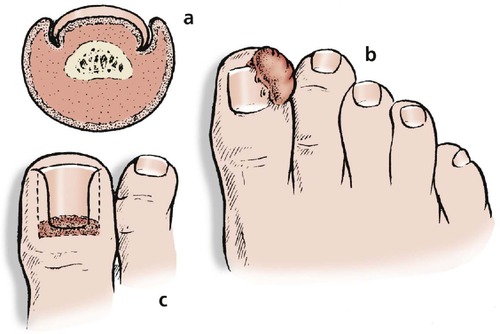

Ingrowing toenail

Toenails are curved, not flat, and the edges can dig into the pulp of the toe (Fig. 25.6). The medial edge of the big toenail is most often affected and will dig into the pulp of the toe, causing soft tissue damage with every step. The damaged area can then become infected, producing a chronic infected granulomatous lesion along the medial side of the big toenail.

|

| Fig. 25.6

Ingrowing toenail: (a) the nail curls into the pulp; (b) the surrounding tissues become swollen and inflamed, perhaps infected; (c) if conservative treatment is unsuccessful, the whole of the nail and nail-forming area must be removed.

|

Treatment

Conservative treatment. This is usually effective and consists of three measures:

1. Regular cleaning.

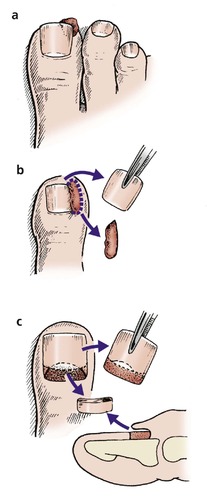

2. Placing a small pledget of cotton wool beneath the edge of the nail (Fig. 25.7a).

|

| Fig. 25.7

Treatment of an ingrowing toenail: (a) protection of sharp corner with wisp of cotton wool; (b) avulsion of the toenail and excision of inflamed tissue; (c) Zadik’s operation to remove the nail and nail-forming tissue.

|

3. Allowing the nail to grow beyond the end of the toe. Cutting it as short as possible leaves a spike which digs into the pulp even more, but letting the nail grow beyond the end of the toe takes the tip of the nail away from the vulnerable soft tissue.

Operative treatment. If conservative measures fail, one of the following operations may be needed:

1. Avulsion of the toenail.

2. Wedge excision.

3. Ablation of the nail and nail bed.

Avulsion of the nail exposes the infected area and relieves the pressure upon it. The infection will subside but the operation does not change the shape of the nail and the problem often recurs when the nail has regrown.

Wedge excision is more radical than avulsion. As well as avulsing the nail the infected and inflamed groove on the medial side of the toe is excised and the medial third of the nail bed removed (Fig. 25.7b). This prevents the medial third of the nail regrowing and allows the wound to heal. The resulting nail is narrower than normal.

Ablation of the nail and nail bed. If the problem recurs after wedge excision the nail and nail-forming tissue should be removed. This operation, called Zadik’s operation, leaves a fibrous scar in place of the toenail (Fig. 25.7c).

The operation is more difficult than it sounds because the fold from which the nail grows is shaped like an envelope and the corners must be meticulously excised. If this is not done a horn of nail will form at each corner of the nail bed and will need to be removed at a second operation. Recurrence can be minimized by applying phenol to the site of the nail-forming tissue. Phenol is also useful in preventing recurrence after segmental wedge excision.

Anaesthetic. If the toe is not infected, the operation can be performed under local anaesthetic using a ring block of plain lidocaine. Lidocaine with added adrenaline (epinephrine) should never be used on a digit because it causes arterial spasm, leading to ischaemia, and gangrene, leading to amputation. Apart from this, infiltration of local anaesthetic can spread the infection. If there is any sign of infection the operation should be performed under general anaesthetic.

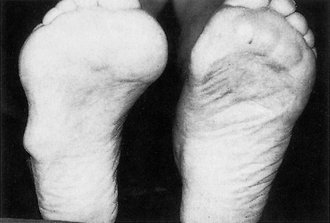

Onychogryphosis

In the elderly, the big toenail can become so thickened and deformed that it resembles a talon (Fig. 25.8).

|

| Fig. 25.8

Onychogryphosis.

|

Treatment

Cutting such a nail is difficult because it is very hard and excision may be needed. In onychogryphosis, the nail forms from the nail bed as well as the nail fold and the whole area must be removed.

Hallux rigidus

Hallux rigidus, which means ‘stiff big toe’, is the result of osteoarthritis confined to the first metatarsophalangeal joint (Fig. 25.9). The cause is not known but is probably some insult to the joint sustained in early life because patients in the second and third decades have the appearances of osteoarthritis appropriate to someone 50 years older. No other joints are affected and the patient’s anxiety that this is the first sign of a widespread crippling arthritis can be allayed.

|

| Fig. 25.9

(a), (b) Hallux rigidus. Premature osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

|

Clinical features

As the joint surfaces become worn, an osteophyte forms on the head of the first metatarsal and dorsiflexion is restricted. The toe gradually becomes more rigid and is eventually fixed in flexion. This has three consequences:

1. The patient can only walk comfortably in bare feet and women find that they cannot wear high heels.

2. The stride becomes shorter because extension of the toe at the end of the stride is lost.

3. The patient learns to avoid stressing the big toe by rolling the weight of the body around the outer edge of the foot instead of over the metatarsal heads. This abnormal gait can cause pain in the ankle and knee.

On examination, osteophytes can be felt around the first metatarsal head and the shoe will show excessive wear under the tip of the big toe.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment consists of wearing low-heeled shoes and a metatarsal bar fixed to the sole of the shoe so that it takes the strain off the first metatarsophalangeal joint. The metatarsal bar is uncomfortable to walk on and sometimes makes the patient trip. If these measures are unsuccessful, operation may be required.

Operative treatment

Excision of the osteophytes and osteotomy of the proximal phalanx is sometimes helpful but the symptoms recur with time.

Excision arthroplasty (Keller’s operation) is sometimes effective, but the resulting pseudarthrosis may also stiffen (Fig. 25.10).

|

| Fig. 25.10

Keller’s operation for hallux valgus and correction of the second toe. The exostosis on the first metatarsal has been levelled, the base of the proximal phalanx excised and the tendon lengthened. The position of the second toe has been corrected with a longitudinal Kirschner wire.

|

Arthrodesis is reliable, but the final position of the toe makes the choice of shoe wear difficult and the operation is usually suitable only for men. The toe should be fixed in slight dorsiflexion and adducted to permit normal walking and shoe wear.

Interposition arthroplasty with a Silastic spacer is often advised but, like any operation in which a foreign body is retained, can be followed by pain and inflammation.

Hallux valgus

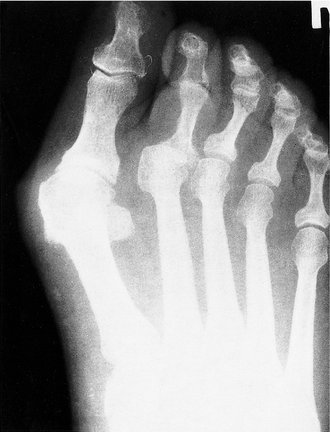

The cause of hallux valgus (Fig. 25.11) is unknown and much nonsense is talked about the evils of pointed shoes and high heels. The condition tends to run in families and is seen in primitive tribes who walk barefoot. There is no evidence at all that shoe wear has any influence, either good or bad, on the development of hallux valgus, although bad shoes can probably aggravate the problem if it is already there.

|

| Fig. 25.11

Pathology of late hallux valgus. The big toe lies in valgus and the second toe may override it or lie beneath it. The second metatarsophalangeal joint dislocates. The extensor hallucis longus tendon acts as a bowstring accentuating the deformity. An inflamed bursa develops over an exostosis on the first metatarsal head.

|

Two main groups of patients are affected by hallux valgus. In the first group, which consists of adolescents and young adults, the condition is often familial and the primary pathology is a varus first metatarsal. The articular surfaces are intact in these patients.

The second group consists of elderly women, and occasionally men, with degenerative changes in the first metatarsophalangeal joint, and secondary deformities in the adjoining toes (Fig. 25.12 and Fig. 25.13). These two groups are very different and should be treated differently.

|

| Fig. 25.12

Hallux valgus in an elderly patient. The great toe is overriding the second toe.

|

|

| Fig. 25.13

Radiograph of a patient with hallux valgus and early osteoarthritis in the first metatarsophalangeal joint with dislocation of the second metatarsophalangeal joint.

|

Conservative treatment

There is no conservative management which corrects the deformity. Sponge pads and splints may be comfortable, but they do not arrest the progress of the condition.

Surgical shoes are helpful in the old and infirm patient, for whom surgical correction is not appropriate, but these shoes are unacceptable to younger patients.

Operative treatment

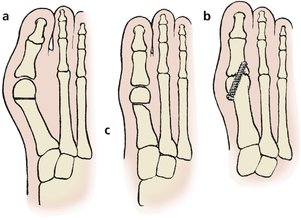

Several operations are available (Fig. 25.14):

|

| Fig. 25.14

(a) Metatarsal osteotomy for correction of metatarsus primus varus and hallux valgus in a young patient. (b) Arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

|

1. Metatarsal osteotomy.

2. Exostectomy.

4. Arthrodesis.

Metatarsal osteotomy is the most popular operation in younger patients and corrects the deformity by moving the whole toe and metatarsal head laterally. The head must also be moved slightly inferiorly to balance the load taken by the metatarsal heads. This procedure is indicated in young patients with intact joints.

Exostectomy. If the main complaint is the bony swelling over the metatarsal head, it is reasonable to excise it but the patient must be warned that the deformity is likely to progress.

Excision arthroplasty or Keller’s operation (see Fig. 25.10) produces a toe that is slightly shorter and more ‘floppy’ than normal. Shortening the toe also has the disadvantage that it allows the sesamoids to slip backwards and leaves the metatarsal head unsupported, which in turn causes pain in the forefoot. The operation is useful for older patients with arthritic joints and secondary deformities.

Arthrodesis is sometimes recommended for hallux valgus but is most useful in men with secondary deformities of the other toes (Fig. 25.14b).

Choice of treatment. Management depends largely upon the age of the patient. Deformities in adolescence are usually the result of a varus first metatarsal, with the toe lying in valgus to compensate. At this age the condition is likely to progress rapidly; no conservative treatment is effective and metatarsal osteotomy is required.

In older patients the main problem is often an exostosis and bursa overlying the metatarsal head. This bump, with its bursa, is popularly called a bunion and may become red, painful or infected (see below).

If there is a varus metatarsal the exostosis and the bursa should be excised and an osteotomy performed. If there is no varus metatarsal or if there is degenerate osteoarthritis as well as hallux valgus, an exostectomy and excision arthroplasty is better.

Bunions

Patients complain of ‘bunions’ but the word means different things to different people (Fig. 25.15). Strictly speaking, a bunion is a bursa over an unduly prominent first metatarsal head or an exostosis on the metatarsal.

|

| Fig. 25.15

Hallux valgus with bursa overlying prominent joint.

|

The bursa can become infected and the infection can spread to the first metatarsophalangeal joint. In patients with diabetes this may lead to gangrene; in patients with rheumatoid arthritis the skin may be very slow to heal.

Treatment

A soft felt pad and comfortable shoes will solve the problem for many patients. If this fails, operation must be considered.

Secondary deformities

Lateral displacement of the other toes

A valgus hallux can push the other toes laterally, sometimes until the big toe lies transversely across the foot with the others resting on it.

Treatment

Although correction of all these deformities is possible, surgical shoes may be preferable to extensive corrective surgery in an elderly patient with a gross deformity.

Dislocated second toe

Subluxation of the second metatarsophalangeal joint with flexion at the proximal interphalangeal (p.i.p.) joint is a common deformity. In some patients, the toe dislocates with the p.i.p. joint fixed in flexion and the proximal phalanx lying on the dorsum of the second metatarsal (see Fig. 25.11).

Treatment

Conservative treatment is not effective, but the toe can be brought into good position by excising the base of the phalanx and arthrodesing the p.i.p. joint.

As for Keller’s operation, the position of the toes can be held with a longitudinal wire.

Subungual exostosis

A small exostosis on the dorsum of the distal phalanx can cause severe pain. The lesion is benign (Fig. 25.16).

|

| Fig. 25.16

Subungual exostosis.

|

Treatment

Excison of the exostosis is the only effective remedy.

Hammer toe

Hammer toe has been described on page 359. Deformities secondary to hallux valgus will recur unless the hallux valgus is corrected. An untreated hammer toe develops a bursa over the p.i.p. joint and a corn beneath the second metatarsal head.

Treatment

Arthrodesis of the p.i.p. joint will correct the deformity but only if the metatarsophalangeal joint is normal. If this joint is dislocated, as it often is, the base of the phalanx should be excised as well.

Mallet toe

Mallet toe (see Fig. 21.21) is a congenital abnormality of the distal interphalangeal (d.i.p.) joint, and is usually familial. The toe interferes with shoe wear and the terminal phalanx may develop blisters.

Treatment

Unless there are troublesome symptoms from the toe, the deformity should be left alone, but arthrodesis or amputation of the terminal phalanx may be needed if there is excessive pressure on the tip of the toe. Conservative treatment is not effective.

Metatarsalgia

Pain in the forefoot, or metatarsalgia, can be due to many things. A prominent metatarsal head is a common cause of pain and can follow any operation on the forefoot, including Keller’s operation (p. 437) or dislocation of the second toe.

Treatment

If soft insoles are not effective, pain from prominent metatarsals may be relieved by a metatarsal osteotomy, which allows the metatarsal head to ride up to a better position and to take a more natural proportion of body weight.

Morton’s metatarsalgia

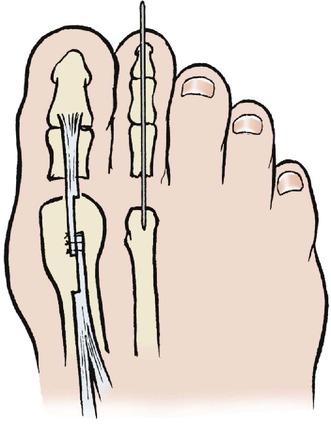

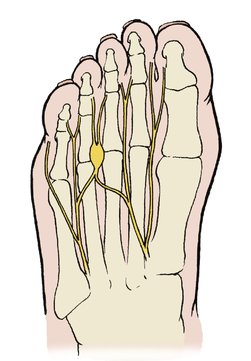

The medial and lateral plantar nerves join in the sole between the third and fourth metatarsal heads (Fig. 25.17). At this point the nerve is subjected to particular pressure and this can produce interneuronal fibrosis within the nerve. A nerve so affected is thickened and the thickening is called a Morton’s neuroma.

|

| Fig. 25.17

Morton’s metatarsalgia.

|

Patients with a Morton’s neuroma characteristically complain of a feeling something ‘like a stone in the shoe’, often accompanied by tingling in the adjacent sides of the third and fourth toes.

On clinical examination the web space between the third and fourth toes is tender, there may be diminished sensibility of the toes, and sideways compression of the foot will produce a painful click. Similar signs and symptoms result from a ganglion in the web space.

Treatment

A small insole to support the metatarsal shaft is sometimes effective but if the symptoms persist despite this and cause genuine disability then the neuroma must be excised.

Freiberg’s disease

The head of the metatarsals may be affected during adolescence by Freiberg’s disease, a vascular osteochondritis similar to Perthes’ disease (Fig. 25.18). The second and third metatarsals are most often involved.

|

| Fig. 25.18

Freiberg’s disease of the metatarsal head.

|

Treatment

Often, no specific treatment is required.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis attacks small joints and the foot is therefore vulnerable. The changes in the foot are similar to those in the hand, with the added complication that the patient must walk on the painful joints.

Involvement of the metatarsophalangeal joints is a special problem. As the tissues become weaker the phalanges move dorsally, bone is destroyed and the transverse pad of soft weight-bearing tissue which normally lies under the metatarsal heads comes to lie underneath the toes instead (Fig. 25.19 and Fig. 25.20). The metatarsal heads are then separated from the ground only by atrophic tendons and thin skin. The bones can erode the skin, leading to infection and further bone destruction.

|

| Fig. 25.19

Rheumatoid arthritis of the feet. Note the prominent metatarsal heads and the rheumatoid nodule.

|

|

| Fig. 25.20

Rheumatoid arthritis of the forefoot with destruction and dislocation of the metatarsophalangeal joints.

|

Treatment

Conservative treatment consisting of soft moulded footwear and careful attention to the skin is very important. Prominent exostoses and metatarsal heads cause skin lesions which quickly extend down to bone, particularly if the patient is receiving steroids.

If conservative measures are ineffective a forefoot arthroplasty must be performed to remove all the metatarsal heads and bring the soft pad of weight-bearing skin back under the metatarsal heads. This is a reliable operation giving good long-term results.

Fatigue fractures

The causes and treatment of fatigue fractures have been mentioned on page 100.

Gout

Gout is described on page 305. Traditionally, the first metatarsophalangeal joint is affected but in fact the other joints are affected just as often.

Flat foot (pes planovalgus)

Generalized ligamentous laxity affects the joints of the foot as well as the rest of the body and the arches of patients with this condition flatten when the foot is weight bearing. Children with flat feet that return to normal when standing on tiptoe or lying on the examination couch are described on page 353.

Painful flat feet are a cause of pain in older patients with degenerative osteoarthritis of the subtalar and midtarsal joints. This is often due to a ruptured tibialis posterior tendon.

Although pes planovalgus does cause pain on walking, corns, verrucae and prominent metatarsal heads are more common causes of pain in the forefoot.

Treatment

Apart from comfortable shoes and a support to the medial arch of the foot, no conservative treatment is effective. If the symptoms are disabling, which is very rare, a triple fusion (p. 353) or calcaneal osteotomy to correct the position of the foot may be required, but most patients manage perfectly well despite their deformed foot. Reconstruction of a ruptured tendon may not be successful and tendon transfers are often needed to restore the arch. In the older patient, a specially made ‘surgical’ shoe may be required.

Fallen arches

Fallen or dropped arches are part of medical folklore. The term is widely used to mean feet that are painful on walking even though the transverse arch probably does not exist and the only arch of any importance is the medial.

Pes cavus

A high arched foot can be due to a congenital bony abnormality but can also be caused by neurological conditions, particularly spasticity of the flexor muscle groups.

Treatment

Provided that there is no underlying neurological abnormality and the foot provides good service, a comfortable shoe is the only treatment required. If the foot is painful or unsatisfactory for any other reason, a corrective osteotomy or soft tissue release may be needed to make the foot plantigrade.

Neurological disorders

One of the pitfalls of orthopaedic surgery is the serious but unusual condition which masquerades as a common problem.

Patients with Friedreich’s ataxia, peroneal muscular atrophy and muscular dystrophy may all present to the orthopaedic surgeon with a foot deformity. Wasting of the calf and peroneal muscles should alert the surgeon to the possibility of a neurological condition being present.

Spina bifida occulta and diastematomyelia both cause tethering of the spinal cord and stretching of the nerve roots with growth. Deformity of the feet is often the first clinical sign. Both conditions are usually accompanied by sensory symptoms and this, with the rapid onset, provides a clue to the diagnosis. Beware of feet that develop a deformity after being normal, and deformed feet with sensory symptoms.

Toe-walkers

Children who persistently walk on tiptoe are described on page 350.

Other causes of foot pain

Do not forget that there are many other causes of painful feet that do not reach a doctor. Chiropodists and podiatrists do an excellent job and probably treat more foot conditions than doctors.