Disorders of Swallowing

Phonation and coordinated movement of liquid and food are the result of complex, integrated, and intact neuromuscular function. When a person’s swallowing function is abnormal because of a structural anomaly, neuromuscular deficit, or postsurgical change, a swallowing function study can be performed. Most swallowing disorders in infants and children are a result of neurologic abnormalities, of which cerebral palsy is the most common.1,2

General Examination Principles

The initial step in the swallowing evaluation is to assess the competence of the velopharyngeal mechanism. First, the patient is observed during quiet breathing and phonation. During feeding, the patient is placed in the true lateral position and is fed contrast material of varying thickness with a bottle with a nipple initially, while swallowing is evaluated in real time with video fluoroscopy, including examination from the mouth to the carina. Either a single image or a sweeping image down to the carina and back to the mouth may be obtained.3–6 Imaging in the frontal projection using a basal or Towne view6 may be performed after lateral imaging; this view permits evaluation of lateral wall movement and correlation with nasopharyngoscopy (e-Fig. 98-1).3,7

If the infant will not take contrast material from the nipple, the contrast material can be introduced into the baby’s mouth carefully with a blunt-tipped syringe (between the cheek and the lateral aspect of the teeth or gums), or a feeding tube can be inserted through the nipple into the baby’s mouth and contrast material can be introduced in a controlled manner under fluoroscopic guidance to initiate swallowing (e-Fig. 98-2). The contrast medium is mixed with increasingly thicker food mixtures, beginning with thin liquids and progressing to solid food if such food is age appropriate. Evaluation of the patient’s ability to handle food with different textures aids in planning an appropriate diet to meet nutritional needs and in planning future therapy. If the patient requires a special diet or only eats certain foods, this food can be brought to the examination and used for the study.

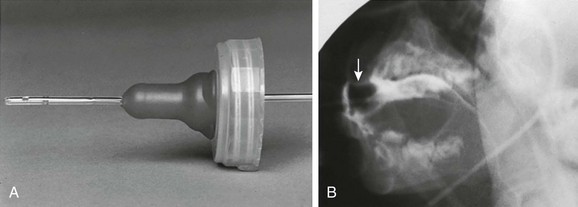

e-Figure 98-2 Modified feeding technique.

A, A number 8 Silastic feeding tube is placed through a nipple so that contrast material can be introduced into the mouth in a controlled manner as the swallowing mechanism is observed. B, Barium outlines the nipple (arrow) and the tube. (Modified from Poznanski A. A simple device for administering barium to infants. Radiology. 1969;93:1106.)

Causes of Swallowing Dysfunction

Central Neurologic Dysfunction

Overview: Cerebral palsy is the most common cause of swallowing dysfunction in infants and children. Other neuromuscular disorders are brainstem dysfunction, cranial nerve abnormalities, intracranial neoplasms, meningomyelocele, muscular dystrophies, and myasthenia gravis. Familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome) leads to autonomic dysfunction with esophageal dysmotility and frequent aspiration pneumonias. Abnormality of the neuromuscular mechanism elevating the soft palate may lead to reflux of contrast material into the nasopharynx, with subsequent pooling of contrast in the pharynx and potential airway aspiration. Abnormalities of other muscle groups lead to defective function of the epiglottis and upper esophageal sphincter, with aspiration into the airway being common1 (Fig. 98-3; Videos 98-1 and 98-2).

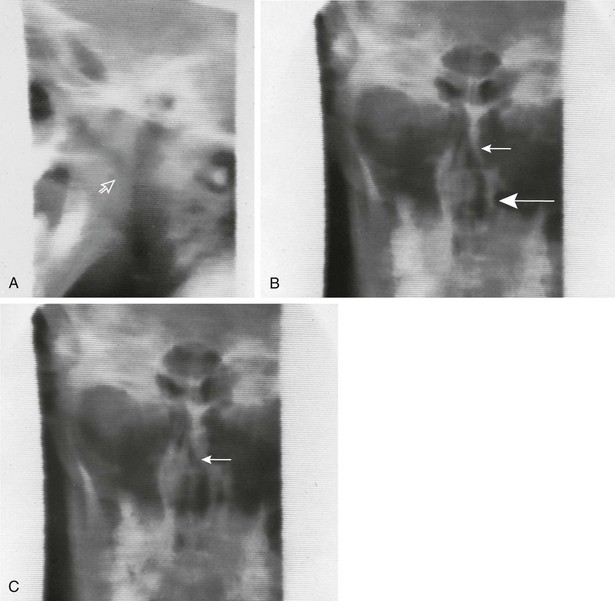

Figure 98-3 Swallowing.

A, As the nipple is inserted into the infant’s mouth, the tongue and soft palate are relaxed and the nasopharynx opens (arrow). B, Normally, the tongue elevates, pushing the nipple to the roof of the mouth, and the soft palate elevates. In this example, the soft palate did not elevate and close off the nasopharynx, resulting in nasopharyngeal reflux (arrow). C, The infant finally did close the nasopharynx by elevation of the soft palate against the adenoid tissue (arrow). Contrast material remains in the nose and in the hypopharynx. D, During this barium swallow study, complete closure of the nasopharynx occurs and no nasopharyngeal reflux is present (asterisk), but aspiration of contrast into the larynx and trachea occurs. E, An oblique view in the same patient as shown in part D reveals extensive airway aspiration during a routine barium swallow study as a result of a lack of coordination during swallowing. Barium coating of the lung parenchyma is present.

Etiology: Swallowing dysfunction is related to dysfunction in one or more of the three phases of swallowing: the oral phase, with the inability to deliver food into the mouth (e.g., poor suck); the pharyngeal phase, with failure to move the food through the pharynx, elevate the soft palate, and close the epiglottis; and/or the upper esophageal phase, with abnormal coordination of relaxation and contraction of the upper esophageal sphincter.1 Swallowing coordination is mediated through the cranial nerves responsible for both sensation and motor function, as well as osseous and muscular structures supplied by both the autonomic and voluntary nervous system. Thus swallowing dysfunction may be due to a large number of conditions that affect any of the mechanical and functional processes necessary for normal swallowing and phonation.

Clinical Presentation: The severity of disordered swallowing and the resultant degree of aspiration will vary with the level of neurologic deficit. Depending on the specific neurologic defect, any or all components of the swallowing mechanism may be affected. Symptoms include nasopharyngeal regurgitation, gagging, coughing and choking during feedings, recurrent pneumonia, malnutrition, and failure to thrive.1,8 However, in some patients at risk for disordered swallowing and aspiration, the gagging and coughing reflex itself may be defective, and these patients are subject to silent aspiration. Because of the risk of silent aspiration in these patients, VFSS should be performed to aid nutritional management and to help reduce aspiration when possible.9

Imaging: During VFSS, contrast material can be seen within the nasopharynx or trachea, with disordered swallowing. Dysfunction in the pharyngeal phase may be related to a mechanical problem such a cleft palate, or weak pharyngeal contraction or lack of coordination may be noted, resulting in inadequate passage of pharyngeal contents, with findings resembling cricopharyngeal achalasia.1,10 It also is important to note whether the patient can spontaneously clear the contrast from an abnormal location and if the cough reflex is present, diminished, or absent (silent aspiration).9

Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment can range from thickening liquids adequately to prevent aspiration to complete oral restriction with enteric tube feeding or total parenteral nutrition. The swallow study can be repeated as the patient matures, or as requested, to assess the effect of any interval medical or surgical treatment.

Congenital Anomalies

Overview: Multiple congenital anomalies can lead to abnormal swallowing. Mechanical problems such as those seen in persons with the Robin sequence who have a small mandible can lead to significant feeding difficulties. Macroglossia, as is seen in patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, can present with similar problems. Disorders of the mouth and jaw such as cleft lip and cleft palate likewise can lead to difficulties with swallowing.7 These disorders are usually readily physically apparent or diagnosed prenatally.

Etiology: The etiologies of the various congenital anomalies that can result in abnormal swallowing obviously are quite different. As an example, cleft palate is a result of the partial or total lack of fusion of the palatal shelves between the eighth and twelfth weeks of gestation.13

Micrognathia may be seen alone or as part of a syndrome such as the Robin sequence and is usually due to incomplete mandibular maturation or failure of normal mandibular development as a result of external causes.14,15

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms correlate with the anatomic abnormality and therefore can vary widely, but they usually include choking, pneumonia, or repeated pneumonitis. Cleft lip and cleft palate occur with varying severity, are usually clinically obvious, and can lead to feeding difficulties by interfering with normal sucking.

Imaging: Conditions such as cleft lip/palate, micrognathia, and macroglossia are not routinely imaged postnatally beyond evaluation of the functional difficulties they produce.11,12

Treatment and Follow-up: Cleft lip/palate are corrected surgically in infancy. Follow-up is usually with endoscopy. Mild micrognathia may be relieved with prone positioning and a nasopharyngeal airway until the infant grows. More severe mandibular hypoplasia that does not respond to conventional treatment may be treated with a distraction osteotomy.14 Macroglossia is treated clinically or surgically with partial, anterior wedge lingual resection to allow for the return of normal swallow function.16

Retropharyngeal Processes—Congenital and Acquired

Overview: Retropharyngeal processes can be congenital or acquired. Cricopharyngeal spasm or achalasia is most often associated with an underlying neuromuscular disorder, but it can rarely occur as a primary abnormality.10 Masses, both benign and malignant, are rare causes of dysphagia and range from those that can be seen in utero, such as lymphatic malformation and cervical esophageal duplication, to lesions acquired postnatally, such as foreign bodies, infectious diseases, and trauma.

Etiology: In patients with cricopharyngeal achalasia, the normal relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle in response to contraction of the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictors does not occur, resulting in a varying degree of obstruction to propulsion of the bolus into the esophagus.10 The swallowing abnormality in patients with a retropharyngeal process is related to the effect of the mass interfering with the coordinated peristalsis needed to effect proper swallowing.

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms of dysphagia vary in presentation according to the underlying abnormality. Congenital masses may have been noted on prenatal imaging, and in some cases, such as lymphatic malformations, they may be visible on physical examination. Onset of dysphagia in conjunction with fever or other signs of infection suggests the presence of a retropharyngeal abscess or superinfection of a preexistent lesion. Prior trauma, such as orogastric tube insertion or caustic or foreign body ingestion, also may produce dysphagia and disordered swallowing.

Imaging: Radiographs of the neck are helpful in assessing whether the airway is narrowed, a mass is pressing upon the airway, or a foreign body is present. In patients with a retropharyngeal process, radiographs demonstrate increased density with mass effect, anterior bowing and displacement, and narrowing of the airway (e-Fig. 98-4). A swallow study demonstrates similar findings for the esophagus.

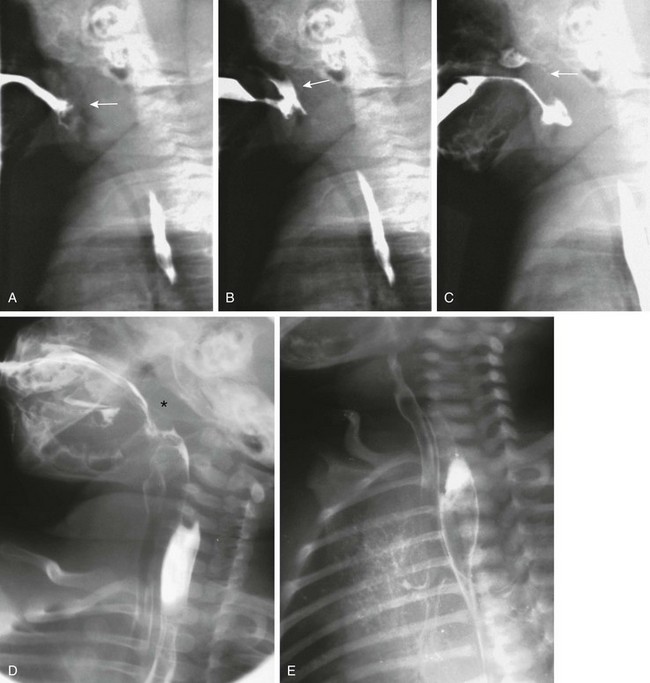

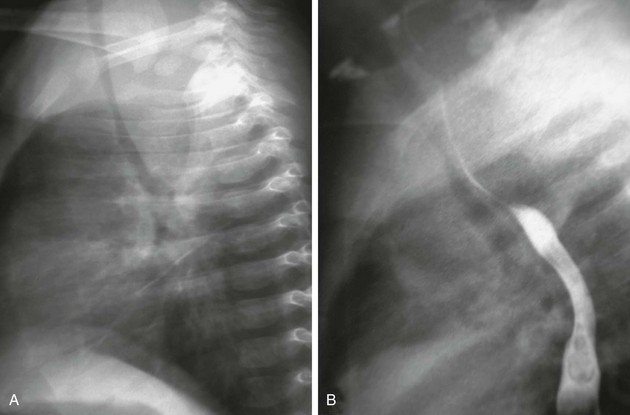

e-Figure 98-4 Prevertebral abscess.

A, A lateral view of a chest radiograph shows a soft tissue density mass in the posterior mediastinum that is compressing and displacing the trachea anteriorly. B, A barium swallow study demonstrates narrowing and anterior displacement of the esophagus and trachea.

In patients with cricopharyngeal spasm or achalasia, VFSS demonstrates the posterior impression of the cricopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 98-5).

Treatment and Follow-up: In patients with cricopharyngeal achalasia, waiting may allow time for maturation, particularly when it is found in premature infants who are otherwise normal. In patients with primary cricopharyngeal achalasia, balloon dilatation has been advocated; surgical management remains controversial.10 Infectious masses are treated with appropriate antibiotics and drainage if necessary. Masses typically are resected, although lymphatic malformations may be treated with sclerotherapy.

Connective Tissue Disorders

Overview: Scleroderma and mixed collagen disorders usually occur in adolescents and adults and are rare in children. Pharyngeal and upper esophageal function is usually normal. Esophageal dysmotility typically begins at the level of the aortic arch. At this level, the esophageal muscle changes from striated to smooth muscle, which is affected more in patients with scleroderma.17 Poor to absent primary peristalsis occurs in the distal two thirds of the esophagus. Secondary gastroesophageal reflux, with or without esophagitis and reflux stricture, may occur.

Dermatomyositis is an inflammatory myositis that primarily affects the striated muscle of the pharynx and upper esophagus. Dilatation of these structures with disordered peristalsis occurs frequently, as does nasopharyngeal reflux of ingested material. The associated vasculitis may result in esophageal ulceration and perforation.18

Etiology: In patients with scleroderma, swelling of endothelial cells occurs, with an adventitial periarterial fibrotic cuff.19 Dermatomyositis is associated with a complement-mediated microangiopathy.20

Clinical Manifestations: The esophagus is involved in nearly all patients with scleroderma, and approximately 50% to 90% have clinical symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, most commonly dysphagia and dyspepsia.19 Dermatomyositis involves the pharynx and upper esophageal sphincter, thus interfering with the appropriate direction of the food bolus into the esophagus. In addition to dysphagia and the inability to swallow without the aid of gravity, patients exhibit hoarseness, nasal speech, and nasal regurgitation.20

Imaging: In older children and adolescents, a chest radiograph may aid the initial workup. The radiograph may demonstrate a dilated esophagus and possibly an air-fluid level. Associated findings of connective tissue disease may be noted, such as interstitial lung disease.

Evaluation of swallowing in persons with scleroderma usually demonstrates a normal swallow mechanism but abnormal distal esophageal motility and dilation (Fig. 98-6). Distal stricture formation usually is related to gastroesophageal reflux as a result of the incompetent lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 98-6 Scleroderma.

Dilatation of the distal esophagus, which was associated with slowed and delayed emptying, and decreased peristaltic activity, in a patient with scleroderma.

Dermatomyositis can cause disordered swallowing of the pharynx and upper esophagus. Reflux of barium into the nasopharynx may be seen.20

Derkay, CS, Schechter, GL. Anatomy and physiology of pediatric swallowing disorders. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1998;31(3):397–404.

Fisher, SE, Painter, M, Milmoe, G. Swallowing disorders in infancy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1981;28:845.

Kramer, SS. Radiologic examination of the swallowing impaired child. Dysphagia. 1989;3:117.

Tuchman, DN. Cough, choke, sputter: the evaluation of the child with dysfunctional swallowing. Dysphagia. 1989;3:111.

References

1. Fisher, SE, Painter, M, Milmoe, G. Swallowing disorders in infancy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1981;28(4):845–853.

2. Lifschitz, CH. Feeding problems in infants and children. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4(5):451–457.

3. Stringer, DA, Witzel, MA. Comparison of multi-view videofluoroscopy and nasopharyngoscopy in the assessment of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Cleft Palate J. 1989;26(2):88–92.

4. Perry, JL. Anatomy and physiology of the velopharyngeal mechanism. Semin Speech Lang. 2011;32(2):83–92.

5. Kramer, SS. Radiologic examination of the swallowing impaired child. Dysphagia. 1989;3(3):117–125.

6. La Rossa, D, et al. Video-radiography of the velopharyngeal portal using the Towne’s view. J Maxillofac Surg. 1980;8(3):203–205.

7. Stringer, DA, Witzel, MA. Velopharyngeal insufficiency on videofluoroscopy: comparison of projections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146(1):15–19.

8. Kramer, SS. Special swallowing problems in children. Gastrointest Radiol. 1985;10(3):241–250.

9. Weir, KA, et al. Oropharyngeal aspiration and silent aspiration in children. Chest. 2011;140(3):589–597.

10. Erdeve, O, et al. Primary cricopharyngeal achalasia in a newborn treated by balloon dilatation: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(1):165–168.

11. Descamps, MJ, et al. MRI for definitive in utero diagnosis of cleft palate: a useful adjunct to antenatal care? Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47(6):578–585.

12. Maarse, W, et al. Prenatal ultrasound screening for orofacial clefts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(4):434–439.

13. Tolarova, MM. Pediatric cleft lip and palate, Medscape Reference. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/995535-overview. [Accessed December 13, 2012].

14. Mackay, DR. Controversies in the diagnosis and management of the Robin sequence. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(2):415–420.

15. Morokuma, S, et al. Abnormal fetal movements, micrognathia and pulmonary hypoplasia: a case report. Abnormal fetal movements. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:46.

16. Heggie, AA, et al. Tongue reduction for macroglossia in Beckwith Wiedemann syndrome: review and application of new technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012. [[Epub ahead of print]].

17. Gaillard, F, Yang, N. Gastrointestinal manifestations of scleroderma (website). http://radiopaedia.org/articles/gastrointestinal-manifestations-of-scleroderma. [Accessed December 13, 2012].

18. Ansell, BM. Juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1992;33:60–62.

19. Ntoumazios, SK, et al. Esophageal involvement in scleroderma: gastroesophageal reflux, the common problem. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(3):173–181.

20. Ebert, EC. Review article: the gastrointestinal complications of myositis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(3):359–365.