Chapter 28 Disorders of menstruation

Menstruation is normal if it occurs at intervals of 22–35 days (from day 1 of menstruation to the onset of the next menstrual period), as mentioned in Chapter 1; if the duration of the bleeding is less than 7 days; and if the menstrual blood loss is less than 80 mL. It was also noted that menstrual discharge consists of tissue fluid (20–40% of the total discharge), blood (50–80%), and fragments of the endometrium. However, to the woman menstrual discharge looks like blood and is so reported.

DEFINITIONS

AMENORRHOEA AND OLIGOMENORRHOEA

Primary amenorrhoea

In many cases, however, no abnormality is found and the young woman may be expected to menstruate in time. Some of these women have an eating disorder or exercise excessively. If an adolescent girl has not started menstruating by the age of 17, investigations should be made as described on page 321.

Secondary amenorrhoea

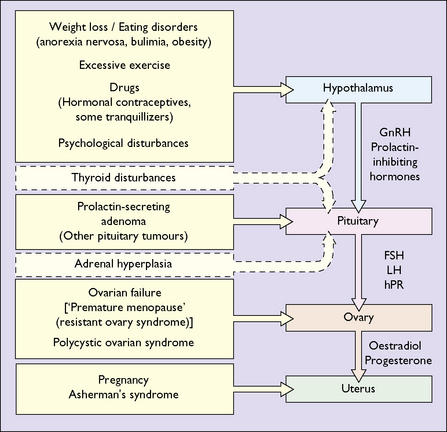

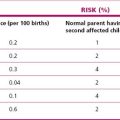

The most common cause of secondary amenorrhoea is pregnancy, but the condition may occur during the reproductive years for a variety of reasons. Figure 28.1 and Table 28.1 show the most common causes of amenorrhoea and their frequency. Only these causes will be discussed in this chapter.

| Cause | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Weight loss, low body weight, exercise | 20–40 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 15–30 |

| Pituitary insensitivity (post-pill) | 10–20 |

| Hyperprolactinaemia | 10–20 |

| Primary ovarian failure | 5–10 |

| Asherman’s syndrome | 1–2 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1–2 |

As noted in Chapter 1, normal menstruation depends on a normal uterus and vagina, and on the reciprocal interaction between hormones released from the hypothalamus (gonadotrophin-releasing hormones), the pituitary (the gonadotrophins – follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)) and the ovaries (oestrogen and progesterone).

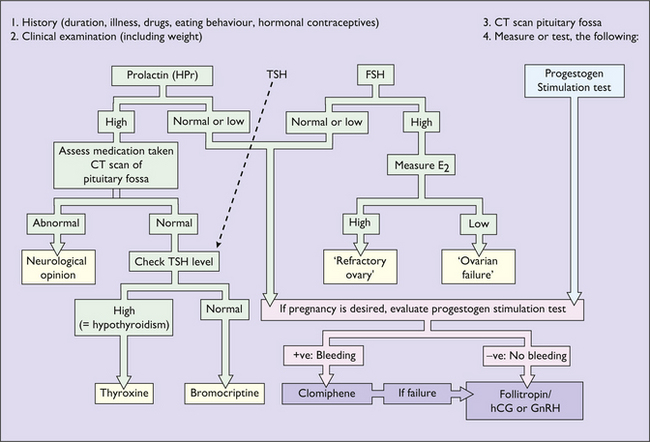

Investigation of secondary amenorrhoea

The purpose of the investigations is to exclude organic disease (for example a prolactin-secreting microadenoma or hypothyroidism) and to treat anovulation as a cause of infertility. If organic disease is not detected and infertility is not a problem, amenorrhoea does not represent a danger to the woman, but because low oestrogen levels may lead to bone loss, after 6 months of amenorrhoea hormone replacement treatment (see p. 325) should be advised.

More common causes of amenorrhoea

Hypothalamopituitary insensitivity: hypothalamic amenorrhoea

Treatment of hypothalamic amenorrhoea

Clomifene is an antioestrogen which may sometimes act as a weak oestrogen. It acts by binding to oestrogen receptors in target cells, thereby preventing oestradiol binding to them. Transferred to the cell nucleus, it renders the cells relatively insensitive to the effects of endogenous oestradiol. This inhibits the negative feedback with the release of GnRH and, subsequently, FSH and LH. The regimen for clomifene use is shown in Table 28.2. Clomifene will induce ovulation in over 80% of women who have hypothalamic amenorrhoea, particularly if the progestogen test is positive, and should be chosen first.

Table 28.2 Therapeutic regimen using clomifene to induce ovulation

| Stage | Month | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Clomifene 50 mg daily for 5 days |

| 2 | 2 | Clomifene 100 mg daily for 5 days |

| 3 | 3 | Clomifene 150 mg daily for 5 days |

| 4 | 4 | Clomifene 200 mg daily for 5 days |

| 5 | 6–8 | No treatment |

| 6 | 9 | Clomifene 100 mg daily for 5 days + hCG 5000 lU 7 days later |

| 7 | 10 | Clomifene 150 mg daily for 5 days + hCG 5000 lU 7 days later |

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

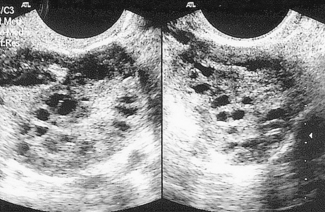

PCOS is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, affecting around 6–10% of premenopausal women. The diagnosis of PCOS is dependent on the exclusion of other causes of androgen excess (pituitary or adrenal disorders) and with the presence of 12 or more primordial ovarian follicles (Fig. 28.3). Obesity is a common feature and its presence extenuates the physical and biochemical abnormalities. Polycystic ovaries are present in 20% of normal females many of whom have androgen levels within the normal range and have regular menses.

Treatment depends on the presenting symptoms and on the wishes of the woman (Box 28.1). If there are no symptoms no treatment is indicated. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged, and obese women persuaded to seek help from an experienced dietitian. If the woman wishes to conceive then metformin, which acts by reducing hepatic glucose production and increasing peripheral tissue sensitivity, and or/clomifene (see above), can be used to induce ovulation. They should be screened for glucose intolerance preferably before conception and certainly during early pregnancy.

Box 28.1 Diagnosis and treatment of PCOS

Treatment

Depends on the presenting symptoms, past history, underlying cause and the wishes of the woman.

Useful medications

Acne and hirsutism

Laser for permanent removal of hair and treatment appropriate for acne should be discussed.

Primary gonadal (ovarian) failure

In most cases the cause of primary ovarian failure is unknown. In this condition the ovarian follicles disappear before the age of 40, and the woman undergoes a premature menopause. In other women the follicles persist but the woman develops autoantibodies that mask the gonadotrophin receptors in the ovaries, with the result that the gonadotrophins can no longer bind to them. These women may have a premature menopause, but inexplicably, some months or years later the woman ovulates and menstruates – the ‘resistant ovarian syndrome’. Treatment consists of providing hormone replacement to control menopausal symptoms and to prevent bone loss and cardiovascular sequelae (see p. 324). If the woman wishes to have a child, she may enter an assisted conception programme and receive a donor ovum.

MENORRHAGIA

Menorrhagia may have an organic cause, but in many instances is dysfunctional; in other words, menorrhagia is due to an alteration in the endocrine or local endometrial control of menstruation (see pp. 11–12). Ovulation has often occurred, but not always. Organic causes include uterine myomata, particularly if the myoma is intramural or submucous and distorts the endometrial cavity; diffuse adenomyosis; endometrial polyps and, rarely, chronic pelvic infection (pelvic inflammatory disease); a blood dyscrasia; and hypothyroidism. If the clinician thinks hypothyroidism is a possible diagnosis, TSH and free T4 levels should be measured. Treatment in these cases is directed to the cause.

Investigation

Transvaginal ultrasound

This is the least invasive method of imaging the uterine cavity. The presence of submucous myomata can be detected and the width of the endometrium measured. An endometrium more than 5 mm wide in a postmenopausal woman indicates the need for curettage to exclude endometrial pathology (Fig. 28.4).

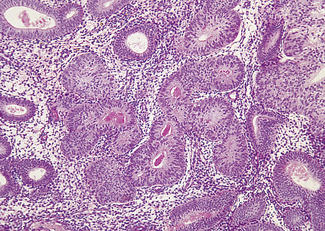

Hysteroscopy

Using a hysteroscope, the uterine cavity can be inspected and abnormalities, such as endometrial polyps (Fig. 28.5) or submucous fibroids, can be detected and often removed. In addition, an endometrial sample can be taken for histological examination. Hysteroscopy is an office procedure that can be performed either with or without a local anaesthetic.

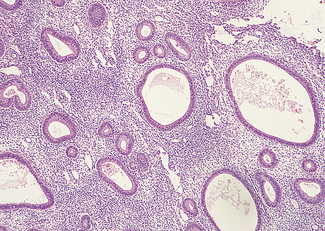

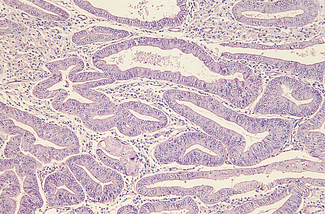

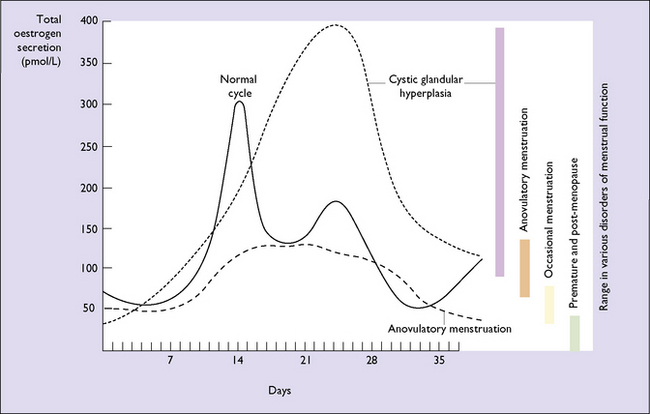

DYSFUNCTIONAL UTERINE BLEEDING

Although dysfunctional uterine bleeding is usually regular the duration of the menstrual cycle may be increased, with the result that the menorrhagia occurs less frequently. In this group of cases, which are usually found at the extremes of the reproductive period, oestrogen secretion may be less than normal and is not opposed by progesterone. In other words, the bleeding is anovulatory. In other cases the unopposed oestrogen levels are high, resulting in an increased thickness of the endometrium and causing cystic hyperplasia (Fig. 28.6). The pathology of an endometrial sample may show simple (cystic) endometrial hyperplasia (Fig. 28.7); complex adenomatous hyperplasia (Fig. 28.8); simple hyperplasia with atypia or complex hyperplasia with atypia (Fig. 28.9). If the pathology shows atypical hyperplasia (the treatment is that described on p. 297) follow-up with further endometrial studies is mandatory (unless the woman chooses to have a hysterectomy), as between 10 and 25% of cases progress to endometrial carcinoma.

Fig. 28.6 Urinary oestrogen secretion in certain gynaecological conditions related to the menstrual cycle.

Treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding

Medical treatment

Surgical treatment

Hysterectomy

Although there is no argument that hysterectomy is an appropriate operation in many cases of uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, advanced endometriosis, uterine malignancy and in some cases of pelvic infection, its position in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding is not so clear. Many women welcome hysterectomy for the relief of a distressing symptom, whereas other prefer to keep organs related to reproduction (ovaries and uterus). A woman must have the opportunity to discuss the choices for the treatment of menorrhagia, and be given time to consider the pros and cons of the operation, if hysterectomy is recommended to her. There is rarely any need for an urgent hysterectomy and, once the operation has been recommended by a gynaecologist, it may be helpful for the woman to talk with her general practitioner about the benefits of and problems related to the operation. These matters are discussed further on page 233.