Disorders of Hyperpigmentation and Melanocytes

Harper N. Price, Ashfaq A. Marghoob

Introduction

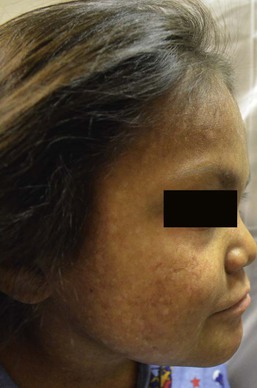

Hyperpigmented lesions, presenting at birth and during the first few weeks of life, are quite common. Pigmented lesions can range from small and isolated to large and multiple. They can exist independently, or in association with other signs and symptoms, and may lead to the diagnosis of a congenital or genetic skin disease. In some cases, hyperpigmented ‘birthmarks’ may not be evident at birth but appear weeks to months later. The relatively light color of infant skin can make some pigmentary disorders difficult to appreciate and thus observation over time may be helpful. Also, over time, melanocytes may produce more pigment and differences between normal and hyperpigmented or hypopigmented skin may become more evident. This chapter serves as an aid for clinicians in diagnosing pigmented lesions in the neonatal and infantile period with an approach based on coloration and localization of lesions with a review of diagnostic criteria, associated conditions, and suggested clinical evaluation when applicable (Table 24.1).

TABLE 24.1

Diagnosis using lesion morphology and location

| Description of lesions | Location or morphology | Possible diagnoses |

| Blue-gray/blue-black patches | Torso Face Shoulder/neck Torso, in association with port-wine stain |

Mongolian spot Nevus of Ota Nevus of Ito Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis |

| Labial macules | Perioral More widespread facial Face/trunk |

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome Carney syndrome LEOPARD syndrome Carney syndrome |

| Face | Centrofacial lentiginosis | |

| Brown sharply defined patches or plaques | Congenital melanocytic nevus Café-au-lait macule |

|

| Small brown macules | Perioral/mucosal Widespread, non-mucosal |

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome LEOPARD syndrome Generalized lentiginosis Inherited patterned lentiginosis |

| Central face/widespread | Carney syndrome | |

| Involves mucosa | ||

| Axilliary/groin/neck only | Neurofibromatosis | |

| Central face only, nonmucosal | Centrofacial lentiginosis | |

| Clustered in a defined body area or segment. Background skin color normal | Segmental lentiginosis Mosaicism |

|

| Clustered in a defined body area or segment. Background skin color darker | Speckled lentiginous nevus | |

| Single | Congenital melanocytic nevus | |

| Linear hyperpigmentation in Blaschko pattern | Flat | Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis (early) Epidermal nevus Incontinentia pigmenti (stage 3) Goltz syndrome Conradi–Hünermann syndrome |

| Raised | Mosaicism Human chimerism Epidermal nevus Incontinentia pigmenti (stage 1, 2) |

Localized hyperpigmentation – tan-brown

Café-au-lait macules

Café-au-lait macules (CALM) are well-circumscribed, oval to round, hyperpigmented hairless macules or patches that may be noted at birth, during infancy or throughout childhood. CALM may have the color of ‘coffee with milk’ in lighter skinned individuals but in darker skinned persons the color may be more medium to dark brown. The size of CALM ranges from a few millimeters to over 20 cm and can occur anywhere on the body (Fig. 24.1). Morphologically, the borders of CALM have been described as smooth (resembling the ‘coast of California’) to jagged contours (resembling the ‘coast of Maine’), correlating with specific disorders. However, in general, this feature varies widely and it not a reliable diagnostic sign.

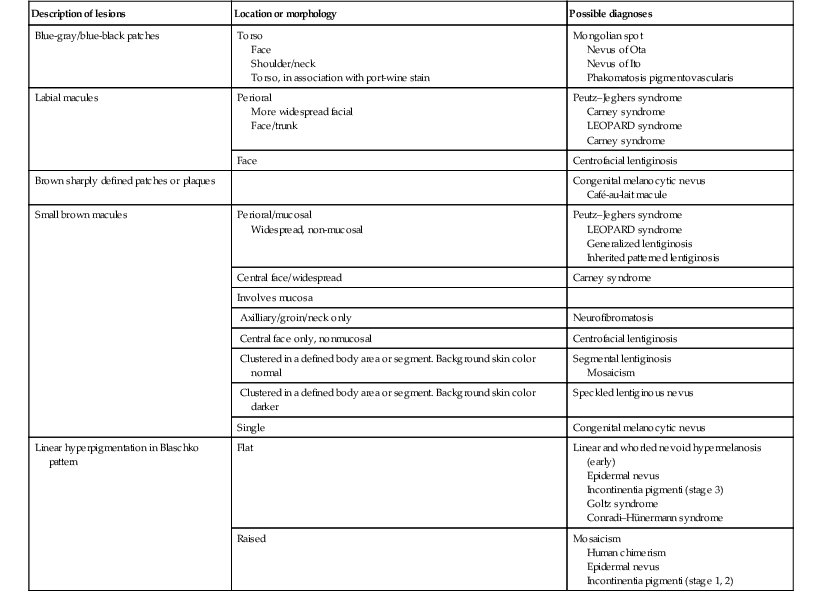

The prevalence of CALM varies in the general population with 2.7% of 4641 newborns having one or more macules in a US study.1 There are great differences in prevalence amongst various racial groups, with an increased number of CALM seen in darker skin types.1–4 A higher prevalence (24.2–36%) of CALM has been reported in older children and young adults as compared with infants.2,3,5 The presence of up to three CALM has been reported in 10–28% of the general population.3,6,7 Multiple CALM, especially six or more, should prompt the clinician to consider underlying disorders (Table 24.2).

TABLE 24.2

Disorders associated with multiple café-au-lait macules (CALM) and associated features

| Strong association | Weaker associationb | ||

| Major features | Major features | ||

| Familial inherited CALMa | Multiple (≥2) generations with multiple (≥10) CALM and other NF-1 stigmata (−) | Tuberous sclerosis | Hypopigmented macules, facial angiofibromas, CNS tubers, retinal hamartomas, renal cysts, angiomyolipoma, cutaneous collagenomas, seizures, mental retardation, cardiac rhabdomyoma, periungual fibromas, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas |

| Neurofibromatosis type I | Skin-fold freckling, neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, neurocognitive deficits, optic glioma, skeletal dysplasia, macrocephaly | Bloom syndrome | Short stature, photosensitivity, susceptibility to malignancy, chronic lung disease, immunodeficiency, cryptorchidism |

| Neurofibromatosis type II | Acoustic neuromas, meningiomas, cataracts, schwannomas, neurofibromas | Ataxia-telangiectasia syndrome | Progressive cerebellar ataxia, lymphoreticular malignancy, cutaneous/ocular telangiectasia, immunodeficiency, hypogonadism |

| Legius syndrome | Macrocephaly, skin-fold freckling, developmental disorders | Silver–Russell syndrome | Congenital short stature and low birthweight, craniofacial and body asymmetry, limb anomalies, microcephaly |

| Watson syndrome | Short stature, pulmonary stenosis, low intelligence, skin-fold freckling | Bannayan–Riley– Ruvalcaba syndrome | Congenital macrosomia, megalencephaly, lipomas, intestinal polyps, vascular anomalies |

| Ring chromosome syndrome | Microcephaly, mental retardation, short stature, skeletal anomalies | Noonan syndrome | Facial dysmorphism, pulmonic valve stenosis, webbed neck, pectus excavatum, mental retardation, short stature, cryptorchidism, hematologic malignancies |

| Hereditary spinal neurofibromatosis | Skin-fold freckling, spinal root neurofibromas | Faconi anemia | Bone marrow failure, limb anomalies, mental retardation, microcephaly, predisposition to malignancy |

| McCune–Albright syndrome | Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, endocrinopathies | Turner syndrome | Short stature, lymphedema, congenital heart disease, valgus deformity |

| LEOPARD syndrome (multiple lentigines syndrome) | Multiple lentigines, hypertelorism, pulmonic valve stenosis, EKG abnormalities, sensorineural deafness, growth retardation, genitourinary abnormalities | ||

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type I | Parathyroid adenoma, pituitary adenoma, pancreatic islet adenoma, lipomas, gingival papules, facial angiofibromas, collagenomas | ||

a Arnsmeier, Riccardi and Paller20 proposed that absence of two consecutive generations of neurofibromas and other non-pigmentary changes of NF-1 allows the diagnosis of familial CALM.

b Syndromes listed have been described with CALM but these are not considered part of the diagnostic criteria, and may not be seen in all cases.

Although the diagnosis is generally made through clinical examination, histologic examination of CALM shows increased melanin content in keratinocytes and melanocytes without evidence of melanocyte proliferation. On electron microscopy, giant melanosomes may be seen. While establishing the diagnosis of CALM, these microscopic features are not useful in determining specific systemic associations (such as neurofibromatosis).

The differential diagnosis of CALM includes a congenital melanocytic nevus, speckled lentiginous nevus, lentigo, Becker’s nevus and forms of pigmentary mosaicism such as nevoid hypermelanosis. Often the distinction will become evident over time. Individual lesions of urticaria pigmentosa or a solitary mastocytoma may also be mistaken for CALM and can be distinguished by the Darier’s sign (the development of urticaria following firm stroking of a mastocytoma) (see Chapter 28).

Treatment of isolated CALM is generally not necessary. Laser therapy, typically with ‘Q-switched’ lasers (Q-switched ruby, Q-switched alexandrite, and Q-switched Nd : YAG), has been attempted for cases considered extensive or disfiguring, but results are inconsistent and repigmentation may occur.8–11 CALM may also paradoxically darken with laser treatment and result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (usually transient).8

Segmental pigmentation disorder (mosaic hyperpigmentation)

Segmental pigmentation disorder (SPD or mosaic hyperpigmentation, pigmentary mosaicism) refers to a hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patch often with a sharp midline demarcation and a less distinct lateral border, commonly located on the trunk.12 Lesions are often noted in infancy and are described in a segmental block-like pattern resembling a ‘checkerboard’13 or following the lines of Blaschko. Those lesions that less commonly involve non-truncal sites (such as the extremity or neck) usually extend onto the torso, and solitary facial involvement has been described. The majority of patients with SPD have no extracutaneous abnormalities. SPD is thought to be due to somatic mutations resulting in cutaneous mosaicism. Extensive cases can be variably associated with chromosomal anomalies. The natural history of SPD has not been reported, but persistence of the hyperpigmentation is expected. A rare biopsy done on a patient with hyperpigmented SPD showed increase melanin in the basal layer, similar to CALM.12

Selected disorders associated with café-au-lait macules

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1)

CALM are usually the first presenting sign in NF-1, and multiple CALM can be seen in 90% of patients with NF-1 on the trunk, buttocks and legs.14 In fair-skinned individuals, CALM may be initially overlooked on cutaneous examination. The number of CALM increases over time during the first decade of life and lesions tend to grow in proportion to the child and may darken with sun exposure. Axillary and/or inguinal freckling is usually absent at birth but present by age 3–5 years, although it may be noted earlier.15 This common feature tends to be the cutaneous sign, along with multiple CALM, that establishes the diagnosis and is felt to be pathognomonic for NF-1.16 Multiple CALM can be seen in other variants of NF, including neurofibromatosis type 2, segmental NF-1 and hereditary spinal neurofibromatosis. A more extensive discussion of NF can be found in Chapter 29.

Legius syndrome

Legius syndrome (neurofibromatosis type 1-like syndrome) is a recently identified autosomal dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the SPRED1 gene.17 The SPRED1 gene is responsible for making spred-1 protein which inhibits the Ras/MAPK pathway. Affected individuals typically have CALM and axillary freckling. However, neurofibromas, typical osseous lesions, Lisch nodules of the iris and central nervous system tumors are characteristically absent. Some patients with Legius syndrome have been described with macrocephaly, a Noonan-like facial appearance, learning disorders, developmental delay and/or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood.17,18 Several families with Legius syndrome have been described with lipomas as well.17–19 Many individuals may meet the NIH diagnostic criteria for NF-1 but gene testing will be negative for mutations in the neurofibromin gene. It is uncertain if there is an increased risk of malignancies. However, some authors have proposed less stringent monitoring in Legius patients as compared to NF-1 patients.18 Screening for developmental delay and behavioral and learning problems is recommended as well as examination and counseling by a clinical geneticist familiar with Legius syndrome.

Familial (inherited) café-au-lait macules

Multiple familial CALM have been described in several families without the other stigmata of NF-1, including the absence of NF-1 gene mutation. SPRED1 had not been tested in these families.20 This diagnosis should only be made in an older child without the other stigmata of NF-1 with a clear family history of multiple CALM without other signs of NF-1.4

McCune–Albright syndrome

The cardinal features of McCune–Albright syndrome (MAS) include polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, endocrinopathies and precocious puberty as well as CALM. MAS is a rare and sporadic disorder caused by a postzygotic mutation in the gene, GNAS1.21–23 The GNAS1 gene encodes for the alpha subunit of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein, causing loss of GTPase activity and increased stimulation of the adenylate cyclase system, resulting in proliferation and autonomous hyperfunction of hormonally responsive cells.24–26 This autosomal dominant mutation is only compatible with life when it occurs in individuals as a postzygotic somatic mutation with resulting mosaicism, which in turn results in marked phenotypic variability.

The CALM seen in MAS are often large, and segmental with favored distribution over the torso and buttocks. They may also follow the lines of Blaschko (Fig. 24.2).27,28 The border of the CALM in MAS is often described as ‘jagged’ and irregular. These cutaneous findings may be present at birth or within the first few years of life and have been noted in approximately 53–98% of patients with MAS.29,30 Melanotic macules of the oral mucosa have also been reported.31,32

Extracutaneous findings in MAS include polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, where bone is replaced by fibrous tissue resulting in asymmetry, bony growths and pathologic fractures; this finding is rarely seen at birth and tends to manifest over time, usually within the first decade. In addition, endocrine abnormalities that may occur include precocious puberty, hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, hyperparathyroidism, hyperprolactinemia, and hypersomatotropism.25,33–35 Neonatal cholestasis, acholic stools and jaundice have been described as presenting symptoms in neonates with MAS.35

Due to the variable clinical expression and segmental nature, diagnosis of MAS may be difficult in infancy. Cutaneous findings of MAS must be differentiated from NF-1. The CALM found in NF-1 tend to be smaller, lighter in color, and more scattered in distribution. Histologic studies would not be helpful in differentiating these disorders. Radiologic studies for MAS may not reveal bony abnormalities in the neonatal period and CALM often precede the development of bony changes by 3 months to 9 years.36 When MAS is suspected, close observation for endocrine abnormalities is warranted. In those with known or suspected MAS, a referral to orthopedics and endocrinology is recommended. Prognosis for MAS is generally favorable and the development of malignancy is rare. Extensive osseous dysplasia early in life, however, portends a poorer prognosis.36

Disorders of dermal melanocytosis

The presence of dermal melanocytes in the skin can give rise to several clinically appearing blue-gray, green or black lesions on the skin including congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots), Nevus of Ota, Nevus of Ito and blue nevi. The blue color is due to the Tyndall effect: the scatter of light passing through a turbid medium, such as the dermis, as it strikes melanin particles.

Congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots)

Mongolian spots are common birthmarks present in over 80% of black and Asian infants compared with only up to 10% of Caucasians infants.37,38 They present at birth, or early infancy, as blue-gray, blue-green, or blue-black macules most often noted over the sacrum and gluteal regions (Fig. 24.3) and less often on extensor extremities and the posterior shoulder. Size can range from a few millimeters to over 10 cm and single or multiple lesions may be present. The borders of Mongolian spots are ill-defined and tend to fade gradually into the surrounding skin color. The coloration will often stabilize in infancy and fade during the first decade of life. Only a small number of lesions persist (3–4%) after adolescence and it has been suggested that these are likely not distinct entities but analogous to Nevus of Ota or Ito.37,39–41 Clinically, these persistent lesions are often blue-black homogenous or speckled patches present in a segmental distribution.

In the Mongolian spot, elongated, slender and slightly wavy dendritic cells containing melanin granules are found in the mid and deep dermis.42 These dendritic melanocytes are present in low numbers and scattered between collagen bundles, both of which are orientated parallel to the skin surface. There is an absence of melanophages. The reason for regression of Mongolian spots and failure of regression of other dermal melanocytic lesions such as nevus of Ito or Ota with age is currently unknown.

Mongolian spots are common, and associated abnormalities are rare. Dermal melanocytosis may be associated with certain lysosomal storage diseases, including gangliosidosis type 1 (GM1), Niemann–Pick disease, Hunter syndrome, α-mannosidosis syndrome, and Hurler syndrome.43 Dermal melanocytosis is generally extensive in distribution often involving the ventral and dorsal aspects of the trunk in addition to the sacrum and extremities.44–50 Mongolian spots may also co-exist within CALM in NF-1.51,52 Dermal melanocytosis is part of the criteria for a subgroup of neurocristopathies labeled ‘phakomatosis pigmentovascularis’ (PPV), in which vascular malformations of the skin, pigmented nevi and Mongolian spots occur together in the same patient (see below). Cleft lip malformation has been associated with adjacent dermal melanocytosis although the significance of the association is unknown.53,54

Differential diagnosis.

Mongolian spots are clinically diagnosed by their common location, congenital or neonatal onset, and morphology, and a biopsy is most often not needed. Other blue lesions include Nevus of Ito, Nevus of Ota, and congenital blue nevus. Location and persistence over time will help in differentiating these entities. A biopsy can be helpful in verifying the dermal location of melanocytes if the diagnosis is in question.

Nevus of Ota (nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, oculodermal melanocytosis)

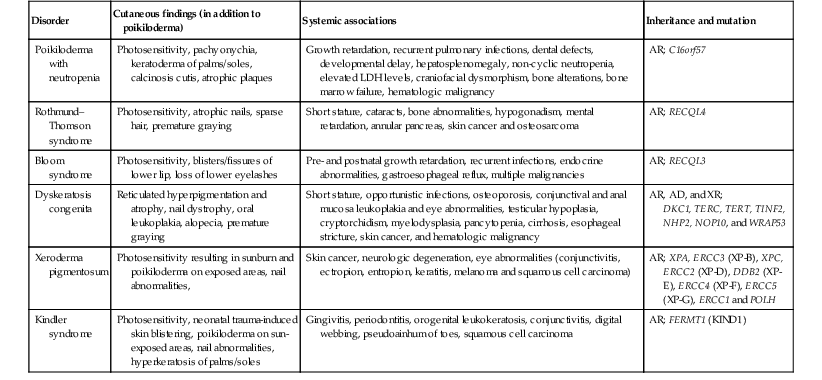

Bluish hyperpigmentation of the skin along the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve is known as Nevus of Ota (Fig. 24.4). These patches can be brown, blue-gray or blue-black, gray or purple and have a speckled or mottled appearance with poorly-demarcated borders. Nodular areas similar to blue nevi can be present.58–61 Nevus of Ota often affects one side of the face and bilateral involvement is described in only 5–10% of patients.62,58,63 Distribution of Nevus of Ota most commonly involves the ophthalmic and maxillary branches with involvement of all three branches of the trigeminal nerve being the least common distribution.41,60,63 This condition is more commonly seen in Asians and has a female preponderance. They may be present at birth or appear within the first year of life, or later between the ages of 11–20 years; mid-childhood onset is rare. Spontaneous resolution does not occur as seen in Mongolian spots. Pathology of cutaneous lesions shows a greater concentration of elongated, dendritic dermal melanocytes scattered within the collagen bundles in the upper dermis (compared with Mongolian spots).

In addition to cutaneous involvement, Nevus of Ota involving the ocular sclera can be seen in two-thirds of patients.64 Pigmentation of the sclera, conjunctiva, cornea, iris and choroid, and less commonly, the optic nerve, retrobulbar fat, orbital periosteum and extraocular muscles can occur. Oral mucosal pigmentation and pigmentation of the tympanic membrane can occur as well.

Most Nevi of Ota pose a potential cosmetic concern but few may be associated with complications. Open-angle glaucoma occurs in approximately 10% of patients due to proliferation of melanocytes in the anterior chamber angle.65,66 The most concerning complication is the development of melanoma within pigmented areas. Malignant degeneration has been reported and may include the eye (choroid, iris, or orbit), skin, and brain.67–69 Sturge–Weber syndrome, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, neurofibromatosis, inflammatory vascular disease, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, multiple hemangiomas, and spinocerebellar degeneration have been described occurring in association with Nevus of Ota.70–75 Rare occurrences of ipsilateral hearing loss with Nevus of Ota have been reported.76,77 Nevus of Ota occurring with nevus flammeus is seen in variants of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Leptomeningeal melanosis and Nevus of Ota can occur concurrently as well.68,69,75,78,79

Treatment and care.

Nevus of Ota tends to increase in size and color intensity over time. An ophthalmologic examination is recommended for those with involvement of periorbital skin, and yearly examinations for those with ocular pigmentation. Dermatologic follow-up is recommended periodically and removal of stable lesions for melanoma prophylaxis is unnecessary since the risk is quite low.58 Opaque make-up may be an option as a means of providing cosmetic improvement. Laser surgery with Q-switched devices (ruby, Nd : YAG or alexandrite) has been shown to reduce the coloration safely and remains the treatment of choice.80–84

Differential diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of Nevus of Ota in a neonate includes a CALM, speckled lentiginous nevus, congenital blue nevus and ochronosis.

Nevus of Ito (nevus fuscoceruleus acromiodeltoideus)

The Nevus of Ito is an analogous lesion to Nevus of Ota with a distribution over the posterior supraclavicular and lateral cutaneous branchial nerves. These blue-gray poorly-demarcated patches may present over the shoulder, supraclavicular neck, upper arm, scapular and deltoid areas (Fig. 24.5). Bilateral nevus of Ito has been reported in a patient with a speckled lentiginous nevus,85 and bilateral Nevus of Ota with a unilateral Nevus of Ito has been noted.86 Cutaneous melanoma and malignant cellular blue nevus have been rarely reported in Nevus of Ito and extracutaneous findings are not seen.87–89

Blue nevi

Blue nevi are dermal melanocytomas that represent benign proliferations of pigment producing dendritic dermal melanocytes (Fig. 24.6). Dermoscopy of common blue nevi reveals uniform blue coloration. Blue nevi are rarely seen at birth, but congenital forms have been described.90–92 Most are acquired, with onset in childhood or adolescence, with predilection for the scalp and face, dorsal aspects of the distal extremities and sacral area. Three types of blue nevi have been described: (1) cellular blue nevus, (2) common blue nevus, and (3) the combined nevus.

Cellular blue nevi seen at birth are rare and have a predilection for the scalp, sacrococcygeal area and buttocks. They present with blue-gray or blue-black nodules or plaques with a smooth or irregular surface texture. Although most congenital cellular blue nevi are small in size (1–3 cm), larger and ‘giant’ lesions can be seen, most commonly on the scalp.93 Melanoma has been described particularly in larger lesions on the scalp.92–104 Multiple satellite blue nevi in association with a large congenital cellular blue nevus have also been reported.93,105 Other related variants of congenital blue nevi include the pauci-melanotic cellular blue nevi, epithelioid blue nevi (also known as pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma), congenital plaque-type blue nevi and neurocristic hamartomas. Multiple blue nevi may be seen in Carney complex (see below) or without associated abnormalities. A rare, congenital, plaque-like type of blue nevus, showing a circumscribed area with numerous macules and papules has been described.106 Blue nevi may arise within speckled lentiginous nevi as well as within other dermal melanocytoses such as Nevus of Ota.58,107,108

Blue-black nodules, papules and plaques seen at birth or infancy are suggestive of blue nevi. A biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis and differentiate lesions from melanoma. Common blue nevi will show pigmented dendritic melanocytes singly or in small aggregations in the reticular dermis, surrounded by thickened collagen. Histopathology of cellular blue nevi, in contrast, shows cellular islands of large spindle-shaped or epithelioid cells with little or no melanin, in addition to pigmented dermal dendritic melanocytes. Lesions may penetrate deep into the subcutaneous fat.42

Treatment and care.

Infants with blue nevi that are not easy to monitor due to location and color, as well as those undergoing rapid growth or symptoms (ulceration, bleeding), should be considered for prophylactic surgical excision. Clinically stable, small common blue nevi without unusual or atypical clinical or dermoscopic features may be monitored. Although malignant blue nevi are rare, new atypical features or symptoms should be evaluated histologically via biopsy or conservative excision.

Mosaic conditions and patterned dyspigmentation (whorled and segmental hyperpigmentation)

Mosaic conditions

Mosaicism is the presence of two or more genetically distinct cell lines in a single individual, which may arise from a variety of genetic defects from separate single mutations, groups of mutations or chromosomal differences.109 Cutaneous mosaicism is associated with diverse pigmentary patterns along the lines of Blaschko or in segmental or block-like patterns, such as the pigmentary anomalies found with hypomelanosis of Ito and McCune–Albright syndrome.27,110–112 Many hyperpigmented conditions present in segmental or Blaschko-linear patterns and may be isolated skin findings or coincide with systemic manifestations (Box 24.1).113,114

Chimerism

A chimera refers to an individual with cells derived from two separate zygotes that can be demonstrated by molecular analysis. Human chimerism is rare. Nevoid hyperpigmentation patterns described in human chimeras have included a flag-like rectangular pattern, a pattern of rounded units (café-au-lait-like patches) and a striated pattern.115

Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis

The term ‘linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis’ (LWNH) is generally used to describe a sporadic disorder of hyperpigmentation in swirls and streaks following a Blaschkoid distribution. Classically, the hyperpigmentation consists of homogenous 1–5 mm macules forming a reticulated configuration and sparing the palms, soles, mucous membranes and eyes.116 Segmental, linear or swirled hyperpigmentation or a combination of these with a sharp midline demarcation is seen over the trunk and less commonly involving the extremities (Fig. 24.7).117 LWNH appears at birth or during the first few weeks to months of life without any preceding inflammatory eruption. The pigmentation may progress for the first 1–2 years of life and then stabilize, possibly becoming less prominent over time. Biopsy of the hyperpigmented macules shows basilar hyperpigmentation with no pigment incontinence or dermal melanophages.116

Systemic abnormalities seen in association with LWNH include neurologic, developmental, musculoskeletal, and cardiac abnormalities that often arise early in life;117–119 LWNH has been described as akin to hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) with cutaneous hyperpigmentation instead of hypopigmentation. No large study exists to define the incidence of systemic features in patients with LWNH. However, systemic comorbidities are described much less frequently in association with LWNH as compared with HI.119,117

LWNH is believed to result from somatic mosaicism of neuroectodermal cells deriving from neural crest, with normal and hyperpigmented skin a result of two distinct populations of cells.116,120 Chromosomal mosaicism has also been described.114,121–126 Although thought to be a sporadic disorder, rare familial occurrences of LWNH have been reported, suggesting an undescribed gene abnormality.127

LWNH is usually diagnosed clinically and should be distinguished from other conditions with Blaschkoid hyperpigmentation (Box 24.1). With diffuse skin disease, it can be difficult to deem which coloration represents the patient’s normal skin and whether the affected areas are represented by hyper- or hypopigmentation. Skin biopsy will enable differentiation from some conditions such as incontinentia pigmenti (IP) and early (macular) epidermal nevus.

Treatment and care.

No specific treatment for LWNH has been described. Thorough history and physical examination should be undertaken to exclude underlying systemic associations. If other anomalies exist, blood and skin fibroblast chromosomal analysis should be considered to look for chromosomal abnormalities.

Incontinentia pigmenti

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP; see also Chapter 29) is an X-linked dominant hereditary disorder found predominantly in females, manifesting with characteristic skin findings, various tooth, eye and nail abnormalities, and neurologic and immunologic impairment. Incontinentia pigmenti is due to a mutation in the IKK-gamma (NEMO) gene.128

The cutaneous findings of the IP syndrome are evident at birth or shortly thereafter and have been classically defined by four stages: (1) vesiculobullous, (2) verrucous, (3) hyperpigmented and (4) hypopigmented.129 However, all four stages may not be seen over time, or they may overlap throughout life. The first inflammatory vesiculobullous stage presents with streaks of eosinophil-filled epidermal vesicles in a geometric fashion, mainly on the extremities, followed by verrucous or lichenoid lesions, and papules and pustules within 2–6 weeks (Fig. 24.8). This stage may persist for several months. Once resolved, widely disseminated hyperpigmentation in a whirled or linear fashion arises, mainly on the trunk. The third stage generally resolves over years and may completely disappear. A fourth stage of atrophy and hypopigmentation, commonly over the lower extremities, may replace the hyperpigmented areas. This stage may be subtle and faint and can be easily overlooked in adult females.130

The differential diagnosis of the hyperpigmented stage of IP includes linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis, macular epidermal nevi and other disorders with Blaschkoid pigmentation.

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) is defined by the presence of a widespread vascular malformation, in particular a capillary malformation (port-wine stain), with cutaneous pigmented lesions such as dermal melanocytosis (usually slate-gray or blue melanosis or Mongolian spot-like) or nevus spilus with various other cutaneous nevi (nevus anemicus, epidermal nevus, cutis marmorata telangiectatica) and possible extracutaneous alterations. Pigmentation in PPV is often diffuse (>50% of the skin) and persistent and does not correlate with the typical locations for Mongolian spots (Fig. 24.9).131

A classification system based upon dominant pigmentary anomalies and subdivisions with extracutaneous findings categorizes four prominent types of PPV (Table 24.3), with type II the most common. The pathogenesis of PPV has been proposed as a phenomenon called ‘twin spotting’.132

TABLE 24.3

Classification of PPV: classification is based on accompanying pigmented nevus

| Type | Vascular malformation | Pigmentary nevus |

| I | Port-wine stain | Epidermal nevus |

| II | Port-wine stain | Dermal melanocytosis (± nevus anemicus) |

| III | Port-wine stain | Nevus spilus (± nevus anemicus) |

| IV | Port-wine stain | Dermal melanocytosis and nevus spilus (± nevus anemicus) |

The designation ‘a’ and ‘b’ was given historically to denote the presence or absence of systemic findings.

Numerous extracutaneous abnormalities may be seen, the most common being an overlap with Sturge–Weber syndrome, as well as Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome and melanosis oculi.133–138

The differential diagnosis of PPV includes capillary malformation-macrocephaly syndrome and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Proteus syndrome may also be considered and is distinguished by the presence of overgrowth, asymmetry and gigantism. Treatment for certain birthmarks, with the aim of improving aesthetics, such as the port wine stain and dermal melanocytosis, can be accomplished with laser therapy.

Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica

Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica (PPK) describes the sporadic concurrence of a Blaschkoid epidermal nevus (organoid or sebaceous differentiation) with a cutaneous pigmentary anomaly such as nevus spilus.139 The name rightly suggests an analogy with PPV and may occur due to the twin spotting genetic mechanism, and/or multilineage somatic mosaicism. In neonates and infants, the speckled lentiginous nevus may appear as a large CALM, prior to the development of ‘speckles’ and papules. Extracutaneous findings are usually present, including neurologic abnormalities (seizures, mental deficiency, hemiparesis and muscular weakness, dysesthesias), skeletal problems (including vitamin D-resistant rickets), and ophthalmologic alterations.139,140 Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma have been reported to arise in the nevus sebaceus and nevus spilus, respectively, and emphasizes the importance for long-term surveillance in these patients.141

Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome

Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome is an autosomal dominant subtype of ectodermal dysplasia syndrome characterized by the development of brown-gray reticulated pigmentation in early childhood without preceding inflammation.142 Pigmentation is localized on the abdomen in most cases but may be periorbital or perioral, or on the neck, flexures, groin or proximal extremities in some cases. Pigmentation gradually increases over the first decade of life and begins to fade after puberty. Sweating is markedly decreased in affected individuals, dermatoglyphics are often absent, and keratoderma of the palms and soles and dental anomalies can be seen. The syndrome is due to a mutation in the KRT14 gene located on 17q11.2-q21 and is allelic to dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis.143

Congenital curvilinear palpable hyperpigmentation (sock-line bands, sock-line hyperpigmentation)

Congenital curvilinear palpable hyperpigmentation is a relatively recently described clinical finding on the posterior legs (usually bilateral posterior calves) of infants (see Fig. 8.27).145 Involvement of the arms (‘mitten-line hyperpigmentation’) and heels (‘heel-line hyperpigmentation’) has also been described.146–148 The hyperpigmented to slightly erythematous plaques are often symmetric, palpable, curvilinear and semicircumferential. Macular hyperpigmentation is also common. The etiology of these lesions is unknown but trauma from tight socks or mittens has been proposed. The pigmentation resolves spontaneously over months to years. Because of the strikingly linear configuration of the lesions, this disorder can be confused with child abuse.

Spotty pigmentation – diffuse

Xeroderma pigmentosum

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder resulting in clinical and cellular sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) light due to a decreased ability to repair DNA damage. XP patients experience cutaneous and ocular photosensitivity and are at increased risk for developing malignancy and pigmentary abnormalities (Box 24.2).

An infant born with XP will manifest skin changes after exposure to UV light, including sunburn after minimal sun exposure. Numerous pigmented macules (0.1–1 cm) will develop on sun-exposed skin, usually by the age of 2 years. These lesions may be brown, gray, or black (although a single lesion will be uniform in color) and may become so dense that they coalesce into larger pigmented patches. The amount of UV exposure correlates with the degree of pigmentation. Clinically, the macules resemble freckles but they are actually solar lentigines and they do not fade over time.149 Hypopigmented or achromic spots develop and are thought to represent mutated melanocytes that have lost the ability to synthesize melanin.150,151 Telangiectasias and atrophy arise with continued UV exposure as the skin undergoes actinic degeneration and these changes may be evident by the teenage years (Fig. 24.10). The skin becomes dry, scaly, and tight appearing. Cutaneous malignancies can arise in the pigmentary stage as well as the atrophic stage and include actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma as well as other rare skin tumors.152–154

Ocular complications are commonly seen in XP patients as the eyelid skin, cornea and conjunctiva are exposed to sunlight. Ectropion or entropion, decreased lacrimation causing exposure keratitis, corneal edema, scarring and vascularization can develop.150 Both benign and malignant neoplasms result, including squamous cell carcinoma and ocular melanoma. An increase in internal malignancies has been reported as well.155 About 20% of patients with XP will develop primary neuronal degeneration resulting in neurologic abnormalities.155–157 These include sensorineural deafness, peripheral neuropathy, microcephaly, cerebral dysfunction (low intelligence, dementia, abnormal electroencephalogram), ventricular dilation and cortical atrophy, choreoathetosis, cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria and abnormal eye movements, and spasticity.152 The age of onset and rate of progression of the neurologic involvement is variable among patients.

XP has been reported worldwide and in all races.150 It can be divided into two major forms: nucleotide excision-repair pathway defects and a variant form (XP-V), in which a defect in the post-replication repair of DNA exists.152 Designation of defects into complementation groups (XPA-G and XP-V) is based on in-vitro cell fusion studies. Different races may have a single dominant complementation group and some groups are made up of only a single kindred. Clinical features are determined by the amount of sun exposure, specific nature of the mutation and complementation group, and other environmental and unknown factors.

Clinical findings at birth in a neonate with XP are lacking and not evident until UV exposure and damage occurs. An infant with significant and early sun burning should prompt further evaluation into photosensitivity syndromes. In addition to XP, other photosensitivity disorders should also be considered (Table 24.4). The differential of multiple pigmented macules includes Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, Carney complex, and LEOPARD syndrome. Histologic findings of cutaneous lesions are nondiagnostic and may show signs of severe photoaging, lentigines or malignancy. Diagnosis confirmation can be done through functional testing to screen cells for abnormalities in DNA repair, but this is available on a research basis only. Commercial molecular genetic testing is available for only a limited number of subtypes and remaining genes may be tested through research laboratories. Testing for prenatal diagnosis on cultured cells from amniocentesis can be performed if a family history of XP exists.

TABLE 24.4

Photosensitivity disorders presenting in the neonatal and infantile period

| Disorder | Defect | Findings |

| Cockayne syndrome | Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the gene encoding the group 8 excision-repair cross-complementing protein (ERCC8) or group 6 excision-repair cross-complementing protein (ERCC6) | Cutaneous erythema with sun exposure in a butterfly distribution, atrophy, telangiectasias, neurologic impairment including ataxia and progressive deafness |

| Trichothiodystrophy (PIBIDS) | Mutation in helicase subunits ERCC2 and ERCC3 | Photosensitivity, ichthyosis, brittle hair, impaired intelligence, decreased fertility and short stature |

| Congenital erythropoietic porphyria | Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the uroporphyrinogen III synthase gene | Burning pain, blisters often with UV therapy for hyperbilirubinemia. Progressive scarring and disfigurement. Pink urine, red teeth, splenomegaly and anemia |

| Rothmund–Thomson syndrome | Compound heterozygous mutation in the DNA helicase gene RECQL4 | Poikiloderma, alopecia, atrophic nails, congenital skeletal abnormalities, short stature, premature aging, and increased risk of malignant disease |

| Hartnup disorder | Mutations in the SLC6A19 gene | Pellagra-like light-sensitive rash, cerebellar ataxia, seizures, hypertonia, cognitive delay |

| Bloom syndrome | Mutations in DNA helicase RecQ protein-like-3 | Poikiloderma, immunodeficiency, growth and skeletal abnormalities, predisposition to malignancy; and chromosomal instability |

Treatment and care.

Management of individuals with XP involves genetic counseling, strict UV exposure avoidance, protective clothing and long hairstyles, sunscreen, sunglasses, protective window coatings and vitamin D supplementation. Skin examinations by the patient/family and dermatologist should be frequent so that malignancy and pre-malignant changes can be caught and treated early. Surgery techniques typically undertaken in normal individuals with skin cancer, such as cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodissection and curettage, Mohs micrographic surgery and the use of topical chemotherapeutic agents, are appropriate. The use of high-dose oral isotretinoin and acitretin has been reported to reduce certain types of new skin cancer formation in XP patients but use is often limited by side-effects, especially in children.158,159 Topical liposome-encapsulated endonuclease has also been reported to decrease the formation of actinic keratoses and basal cell carcinomas in XP patients.160 Radiation therapy has been used successfully in treatment of aggressive skin cancers in patients with XP, as these patients tend to have a normal cellular and clinical response to ionizing radiation.161 Death may occur in individuals with XP due to cutaneous or internal malignancy or neurologic degeneration.

Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) refers to the term used to describe brown, blue or grayish macules and patches after an exogenous or endogenous insult. PIH can be seen at birth and early on in life. Common exogenous causes in hospitalized infants include the use of tape, adhesive from monitoring leads, and mechanical trauma, which forms distinct patterns. More indistinct forms may result from endogenous inflammatory processes seen in neonates, such as seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis. In certain skin diseases such as morphea and lichen planus, PIH presents as a definitive morphological feature; however, almost all skin disease which results in inflammation can cause PIH. Those infants with darker skin types tend to be at higher risk for developing hyperpigmentation as compared to those with lighter skin.

A history of contact, trauma, or previous inflammatory process may be the clue to diagnosis. Epidermal melanocytes increase in size, number and melanin production following stimuli, including certain inflammatory diseases. When biopsied, the dermoepidermal junction and basal layer are disrupted by epidermal injury and melanin passes from its usual epidermal position to the dermis, subsequently engulfed by macrophages to form melanophages.162 PIH takes time to resolve, as dermal melanin is slow to break down.

The differential diagnosis of PIH tends to be one of exclusion; certain patterns due to a particular contact are suggestive. Preceding history of an inflammatory event is helpful. A Wood’s light may aid in determining the extent of pigment alteration as it accentuates epidermal melanin. In rare cases, a biopsy may be indicated and shows melanophages in the superficial dermis and basal layer along with a variable infiltrate of lymphohistiocytes around superficial blood vessels and in dermal papillae. PIH may also be seen as a part of transient neonatal pustular melanosis (see Chapter 7) but, interestingly, a biopsy will not show dermal melanophages.162 Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity have been described to display ecchymotic-like blue-brown discoloration prior to the atrophic stage of these iatrogenic lesions.163 Hyperpigmentation usually fades over time especially when pigment is epidermal.

Universal melanosis and progressive familial hyperpigmentation

A case of a healthy infant, born with white skin to Mexican parents, was described to develop progressive black pigmentation at 15 days of age that became diffuse by the age of 21 months, involving a portion of the palms and soles, nails, and oral and ocular mucosa.164 The infant was otherwise well and developmentally normal. A skin biopsy revealed heavy hyperpigmentation of all epidermal layers and pigment-loaded histiocytes in the dermis. This condition was thought by the authors to be due to an overproduction of melanin and termed ‘universal acquired melanosis’ or ‘carbon baby’. Other similar reports in the literature occurring in families have been termed, ‘melanosis universalis hereditaria’,165 ‘melanosis diffusa congenita’,166,167 ‘universal acquired melanosis’,164 ‘familial progressive hyperpigmentation’,168 ‘familial universal melanocytosis’, or ‘diffuse melanosis’.169 It is unclear whether these cases represent the same entity or different disorders. In general, these progressive conditions tend to describe the onset of hyperpigmentation at birth or during early infancy that progresses in extent with age. Familial progressive hyperpigmentation was originally described as hyperpigmentation in a variety of variably sized dots, whirls, streaks, and patches, in contrast to universal acquired melanosis where the entire integument becomes black.164,168 Inheritance has been described in many of these similar disorders as autosomal dominant, possibly due to a heterozygous gain of function mutation in the KIT ligand gene.170 Systemic manifestations do not occur, but irregular pigmentation of nails, oral and ocular mucosa and palms and soles have be seen. Histopathology of reported cases showed epidermal hypermelanosis with dispersed and widely distributed melanosomes within keratinocytes. The clinical features as well as the histologic absence of melanin incontinence should differentiate these conditions from IP, Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome and LWNH.

Poikiloderma

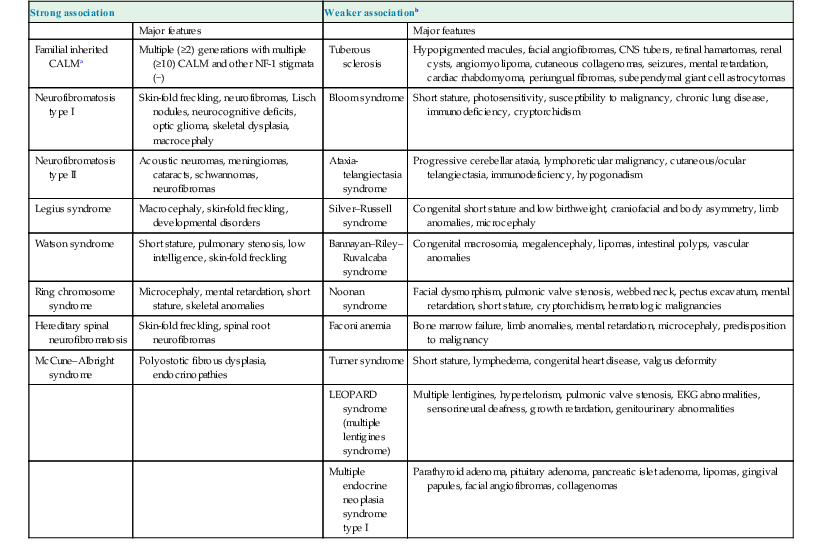

Poikiloderma describes the cutaneous findings of atrophy, hyper- and hypopigmentation and telangiectasias that characterize several genetic disorders (Table 24.5, Fig 24.12). This clinical finding may be present at birth, during infancy, or develop in the first few years of life. Poikiloderma may present as a later finding in xeroderma pigmentosum, connective tissue disorders, Cockayne syndrome and Faconi anemia.171

TABLE 24.5

Disorders with congenital/infantile poikiloderma

| Disorder | Cutaneous findings (in addition to poikiloderma) | Systemic associations | Inheritance and mutation |

| Poikiloderma with neutropenia | Photosensitivity, pachyonychia, keratoderma of palms/soles, calcinosis cutis, atrophic plaques | Growth retardation, recurrent pulmonary infections, dental defects, developmental delay, hepatosplenomegaly, non-cyclic neutropenia, elevated LDH levels, craniofacial dysmorphism, bone alterations, bone marrow failure, hematologic malignancy | AR; C16orf57 |

| Rothmund–Thomson syndrome | Photosensitivity, atrophic nails, sparse hair, premature graying | Short stature, cataracts, bone abnormalities, hypogonadism, mental retardation, annular pancreas, skin cancer and osteosarcoma | AR; RECQL4 |

| Bloom syndrome | Photosensitivity, blisters/fissures of lower lip, loss of lower eyelashes | Pre- and postnatal growth retardation, recurrent infections, endocrine abnormalities, gastroesophageal reflux, multiple malignancies | AR; RECQL3 |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | Reticulated hyperpigmentation and atrophy, nail dystrophy, oral leukoplakia, alopecia, premature graying | Short stature, opportunistic infections, osteoporosis, conjunctival and anal mucosa leukoplakia and eye abnormalities, testicular hypoplasia, cryptorchidism, myelodysplasia, pancytopenia, cirrhosis, esophageal stricture, skin cancer, and hematologic malignancy | AR, AD, and XR; DKC1, TERC, TERT, TINF2, NHP2, NOP10, and WRAP53 |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum | Photosensitivity resulting in sunburn and poikiloderma on exposed areas, nail abnormalities, | Skin cancer, neurologic degeneration, eye abnormalities (conjunctivitis, ectropion, entropion, keratitis, melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma) | AR; XPA, ERCC3 (XP-B), XPC, ERCC2 (XP-D), DDB2 (XP-E), ERCC4 (XP-F), ERCC5 (XP-G), ERCC1 and POLH |

| Kindler syndrome | Photosensitivity, neonatal trauma-induced skin blistering, poikiloderma on sun-exposed areas, nail abnormalities, hyperkeratosis of palms/soles | Gingivitis, periodontitis, orogenital leukokeratosis, conjunctivitis, digital webbing, pseudoainhum of toes, squamous cell carcinoma | AR; FERMT1 (KIND1) |

AR, autosomal recessive; AD, autosomal dominant; XR, X-linked recessive.

(Adapted from: Chantorn R, Shwayder T. Poikiloderma with neutropenia: report of three cases including one with calcinosis cutis. Pediatr Dermatol 2012; 29(4):463–472.)

The pathogenesis and etiology of poikiloderma are unknown, but commonly associated with UV exposure. The diagnosis is made by the typical clinical appearance of the reticulated eruption of telangiectasias and hypo- and hyperpigmentation. Histologic features depend on the severity and stage and include varying degrees of epidermal atrophy with hyperkeratosis, dilated vessels, hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, pigment-laden macrophages, and a dermal band-like or perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes.172 The prognosis is dependant on the underlying associated disorder, and prompt recognition will aid in early diagnosis, monitoring and implementation of sun-avoidance behaviors.

Metabolic causes

Addison disease and adrenocortical-unresponsiveness syndrome

Addison disease is adrenocorticoid deficiency resulting from dysfunction or destruction of the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid production is affected. Although onset is usually in adulthood it may present earlier in congenital adrenal hyperplasia, due to a disorder of long-chain fatty acid metabolism, or polyglandular autoimmune syndromes.

Hyperpigmentation of skin and mucous membranes often precedes symptoms and is due to the stimulant effect of excess ACTH (adrenocorticotrophic hormone) and MSH (melanocyte-stimulating hormone) on melanocytes.173 Pigmentation may present as diffuse tan, brown, or bronze darkening of skin surfaces, especially on sun-exposed areas, including nails and palmar creases, and blue-back patches on mucosal surfaces (including oral and anogenital mucosa). Associated signs and symptoms include weakness, weight loss, hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia and eosinophilia.

ACTH-insensitivity syndrome (or adrenocortical-unresponsiveness syndrome), a congenital insensitivity to functionally normal ACTH secretion, causes diffuse hyperpigmentation in the neonatal period and may precede systemic symptoms.174,175 Histologic findings of the hyperpigmentation are nondiagnostic and include increased epidermal melanin in keratinocytes and no increase in melanocytes.

Lentigines

LEOPARD syndrome (multiple lentigines syndrome, Moynahan syndrome)

The acronym LEOPARD was proposed by Gorlin to describe a heterogeneous syndrome that includes cutaneous lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction defects, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth and sensorineural deafness.176 This rare autosomal dominant condition with variable expressivity involves cutaneous features as well as multiple organ systems. The originally described mutation responsible for LEOPARD syndrome (LS) was found on the gene PTPN 11, which has a dominant negative effect, interfering with growth factor/Erk-MAPK signaling.177,178 Additional mutations in BRAF and RAF1 have now been described and found to be associated with LS.179,180 LS is allelic to Noonan syndrome with many overlapping findings.

Lentigines can be noted during infancy as flat black-brown macules that increase in number until puberty, being generalized, with a predominance on the face, neck and upper trunk and usually sparing the mucous membranes. Lesions may not appear until childhood and the total number may be in the thousands; however, cases without lentigines have been reported. When biopsied the pigmented lesions reveal features of typical lentigines, displaying elongation of rete ridges, an increase in the concentration of melanocytes in the basal layer (without nests) with an increase in the amount of melanin in melanocytes and keratinocytes, as well as melanophages in the upper dermis.42 Café-au-lait macules are also seen in up to 70–80% of patients with LS and can predate the appearance of lentigines.181

In addition to lentigines, the majority (85%) of those with LS have heart defects, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and pulmonary valve stenosis.182 Congenital heart disease is often the most urgent medical issue during the first months of life and remains the leading medical issue for those patients that will eventually carry the diagnosis of LS.183 Facial anomalies (mild or marked) are also invariably present in many patients with LS, although they are not diagnostically specific for the disorder.183 Postnatal growth retardation, sensorineural hearing deficit and intellectual disability are less common associations but they are part of the classically described syndrome. Genital anomalies are seen predominantly in males and include gonadal hypoplasia, hypospadias, and delayed puberty. Various craniofacial and skeletal anomalies have been described including short stature, pectus excavatum, kyphosis, ocular hypertelorism, and mandibular prognathism.

The diagnosis of LS is based on the cutaneous and systemic findings. Diagnostic criteria have been suggested: (1) if lentigines are present, at least two of the six other features are needed to make the diagnosis; (2) if lentigines are absent, an affected first-degree family member with LS and three of the six other features are needed for diagnosis.184,185 The differential diagnosis includes both generalized and patterned lentiginosis, namely Carney complex and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (see below). The lentigines seen in XP can be widespread but are not present at birth and occur after UV exposure. In LS, the presence of lentigines is independent of UV exposure.

Treatment and care.

In patients with lentigines noted at birth or during the neonatal period, evaluation should include a complete physical examination for associated extracutaneous findings, electrocardiogram (ECG), hearing evaluation, and other studies prompted by signs and symptoms. Abnormalities should be monitored by the appropriate specialist and genetic counseling should be provided. Treatment of lentigines has been attempted with cryotherapy and various lasers in some patients. The end results of these treatments are quite variable. It is generally not recommended in early childhood.186–189

Carney complex (NAME/LAMB syndrome)

Several previous descriptions of the syndromes now consolidated under the term Carney complex represent various manifestations of this complex. These include NAME syndrome (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibromata, ephelides) and LAMB syndrome (lentigines, atrial myxoma, myxoid tumors, blue nevi).190–192 Carney complex is an autosomal dominant multiple endocrine neoplasia disorder characterized by lentigines, endocrine hyperactivity, cardiac myxomas and schwannomas.

The cutaneous findings in Carney complex include lentigines, café-au-lait macules, and blue nevi. Lentigines occur shortly after birth and are concentrated over the central facial area and can involve the mucosa. They can also extend to the neck, trunk, extremities and genitalia. Associated nevi can be congenital or arise later in infancy. Nontender dermal nodules, or cutaneous myxomas, do not often develop until the second decade of life and are typically located on the head and neck. Associated noncutaneous findings in Carney complex include cardiac myxoma, endocrine diseases and tumors (Cushing syndrome, acromegaly), testicular tumors (in particular, Sertoli cell tumor), psammomatous melanotic schwannomas and possibly other benign and malignant neoplasms such as ductal adenoma of the breast.

Carney complex is due to a mutation in the PRKAR1A gene on chromosome 17q23.193 This gene encodes the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A and functions as a tumor-suppressor gene. Linkage to the short arm of chromosome 2 has also been described in 11 kindreds with clinical findings of Carney complex, indicating genetic heterogeneity.194

Other multiple lentigines syndromes need to be differentiated from Carney complex, including LEOPARD and Peutz–Jeghers syndromes. If a neonate has skin findings suggestive of Carney complex, evaluation by cardiology, endocrinology, and urology is warranted, and genetic counseling should be offered.194

Spotty pigmentation – localized

Segmentally distributed spotty hyperpigmentation consists of groups of lentigines present in large numbers or in a distinctive localized distribution, with or without accompanying extracutaneous findings. Several designations exhibit clinical and semantic overlap, such as unilateral lentiginosis, segmental lentiginosis, lentiginous mosaicism and speckled giant café-au-lait macule. It is important to distinguish cutaneous-only conditions from familial lentiginosis syndromes or sporadic spotty pigmentation syndromes with possible associated anomalies. Histopathologic features of lentigines include increased numbers of melanocytes in the basal layer along with elongated epidermal rete ridges. Histopathology is not helpful in ascertaining a diagnosis. The following section describes particular entities with localized or segmental lentigines.

Centrofacial lentiginosis

Lentigines with involvement of the central face without further extension to other areas of the skin or mucosa have been termed ‘centrofacial lentiginosis’. Onset is usually in infancy and autosomal dominant inheritance is suggested. In adulthood, the lentigines often fade. Centrofacial lentiginosis may be associated with skeletal and bony abnormalities, neurologic manifestations, developmental and psychiatric symptoms and endocrine dysfunction.195

Segmental lentiginosis (partial unilateral lentiginosis, lentiginous mosaicism)

Asymmetric segmental distribution of lentigines in large numbers usually designated to one side of the body has been termed segmental lentiginosis (also reported as partial lentiginosis, unilateral lentigines or agminated lentiginosis).196 It has been suggested that some of these cases may actually represent a speckled lentiginous nevi, epidermal nevus or LWNH.197,198

Another term, ‘partial unilateral lentiginosis’ (PUL), has been coined to describe small clustered hyperpigmented macules distributed in a unilateral limited area of the body (sometimes in a segmental pattern), usually involving the face, neck, and upper trunk.199 These macules overlie normal skin and they have a sharp midline demarcation. Histologically lesions show features of lentigo simplex without nevus cells being present, although small nests of melanocytes have been described at the tips of the rete ridges, forming a ‘jentigo’ pattern.200,201 Lesions appear in childhood, as early as one year of age, but are rarely seen at birth. PUL has been associated rarely with central nervous system diseases (epilepsy, mental retardation, intracranial vascular malformations).202–204 Familial inheritance has not been described.

Segmental lentiginosis should be differentiated from other segmental disorders including speckled lentiginous nevus, segmental NF and agminated Spitz nevi. Wood’s light examination and skin biopsy may be helpful in these cases. Destruction of lentigines via laser or cryotherapy can be performed if desired.189

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is one of the most well-known familial lentiginosis syndromes. It is dominantly inherited and caries a risk of solid tumor malignancy.205,206 A key cutaneous diagnostic feature of PJS is dark brown-blue macules on the oral mucosa (buccal mucosa, palate, gingival), border of the lips (Fig. 24.13), and palms/soles, eyes, nares and perianal region.207,208 Pigmented bands in the nail plates can also be seen. The macules typically appear in childhood but can be present at birth and may fade in late adulthood. Mucosal lentigines tend not to fade. In addition, patients with PJS can have pigmented macules of the bowel mucosa, intestinal hamartomatous and adenomatous polyps (found in the jejunum, ileum, colon, rectum, stomach and duodenum). There is also an increased susceptibility to benign and malignant tumors including benign ovarian sex cord tumors, calcifying Sertoli tumors of the testes, cervical, breast, pancreatic, endometrial and gastrointestinal cancer.

PJS is mainly due to a heterozygous mutation in the serine threonine kinase STK11/LKB1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene.209,210 Disease manifestations are triggered by the loss of the functional copy of the gene in somatic cells.

Histopathology of the cutaneous pigmented macules is typical for lentigines (see above). Abdominal pain, melena, or intussusception may be the presenting sign in individuals with intestinal involvement. The differential diagnosis of neonatal lentigines includes LEOPARD syndrome, Carney complex, and generalized lentiginosis. For patients with PJS, hematocrit and stool guaiacs are recommended in childhood and polyps may require surgical intervention for symptom relief. Referral to gastroenterology is needed for continued surveillance for malignancy of the GI tract, and medical screening with interval history and physical examinations of other associated organs to monitor for malignancy should be undertaken.

Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome

Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba (Riley–Smith, Bannayan–Zonana, and Ruvalcaba–Myhre–Smith syndromes) is an autosomal dominant phenotypically variable disorder under the heading of ‘PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes’ due to the discovery of mutation in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN in up to 60% of patients.211 Mutations in this gene are also described in Cowden syndrome and other related hamartoma syndromes.209,210 Vascular anomalies and intestinal hamartomatous polyps have also been described.

Lentigines, 2–6 mm in size commonly occur on the glans and shaft of the penis or on the vulva of females. These may be present at birth or infancy, or develop during childhood and adolescence.212,213 Other cutaneous findings may include single or multiple café-au-lait macules, subcutaneous lipomas, vascular anomalies, facial papules (displaying features of trichilemmomas and verrucae),214 oral and perianal papillomas, acrochordons, acral keratoses and acanthosis nigricans.

Noncutaneous findings in BRRS include the common findings of macrocephaly (without ventricular enlargement) that may be noted at birth or infancy. About half of the patients will have neurologic abnormalities including hypotonia, delayed psychomotor development, mental deficiency and seizures.214 Visceral lipomas, hamartomatous intestinal polyps (45% of patients),215 skeletal abnormalities and joint hyperextensibility may also be seen. Retinal abnormalities such as prominent Schwalbe lines and corneal nerves may be noted in 35% of patients as well as pseudopapilledema.216,217 A myopathic process described in BRRS has shown a lipid storage myopathy on muscle biopsy, predominantly in enlarged type 1 skeletal muscle fibers.218,219 Thyroiditis and thyroid neoplasms have been reported.215

BRRS is allelic to Cowden syndrome with many overlapping cutaneous and systemic features; however, Cowden syndrome has a later age of onset, usually in adulthood. Patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome do not have the genital distribution of lentigines as in BRRS. Proteus syndrome, another multiple hamartoma syndrome, presents with pigmented lesions consistent with epidermal nevi and Blaschkoid nevoid hypermelanosis, which should be easily distinguishable from BRRS. Genital lentigines in BRRS may be subtle and easily overlooked. Recognition of the disorder should prompt referrals for management of associated systemic conditions.

Pigmentary variations

Dyschromatosis

The dyschromatoses are a group of disorders described by both cutaneous macular hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation and a lack of atrophy or telangiectasias as seen in poikiloderma. Macules are irregular in shape and small in size. The dyschromatoses have been divided into two major forms, designated ‘dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria’ and ‘dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria’.

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH) is used to describe patients with both hyper- and hypopigmented macules on the extremities, in particular, the dorsal hands and feet, sparing the palms and soles and mucosa. Most cases have been described in Japan and China and show an autosomal dominant inheritance.220 The majority of patients will develop skin findings before the age of 6 years.220 Facial lesions can resemble ephelides and these lesions do not fade over time. DSH tends to be found in primarily sun-exposed areas but there is no evidence of photosensitivity in these patients. DSH can be caused by a heterozygous mutation in the adenosine deaminase, RNA-specific gene DSRAD on chromosome 1q21.221,222

Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria (DUH) consists of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules in a diffuse pattern, mainly truncal, reported in families with possible autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance. The majority of patients present by age 6 years or younger as in DSH, and cases noted at birth have been reported.220 Mucous membrane lesions and lesions on the palms and soles may occur in DUH. Rare noncutaneous associations with deafness, short stature, as well as hematologic and tryptophan metabolic abnormalities have been reported in patients with possible DUH.223,224

Pigmentary demarcation lines

Pigmentary demarcation lines are natural pigmentary boundaries mostly described and seen in black and Asian patients. These lines have been categorized into five groups, designated A–E.225 Group A (anterior brachial) designates lines along the upper limb with variable trans-pectoral extension;226 group B lines are along the medial lower limbs; group C lines are paired lines in median or paramedian courses on the chest with midline abdominal extension; group D lines describe a posteromedian demarcation, and group E are bilaterally symmetric, obliquely orientated hypopigmented macules on the chest/periareolar region.

Groups A and C are most commonly described and distinct. Group A lines were described in 20%, 29%, and 37% of examined black patients by Futcher, Vollum, and Selmanowitz, respectively, and 6% of Japanese patients.225–227 The degree of overall skin pigmentation did not seem to correlate with incidence of A lines. Lines tended to be more apparent in the older population. Group C lines were noted in more than 30% of black patients.228,229 Group E lines have been described more often in children (69%) and seem to become less noticeable over time.230

Congenital melanocytic nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are hamartomatous proliferations of neuroectoderm elements comprised mainly of melanocytes with variable numbers of nevus cells and other neural elements. Their presence is determined in utero and hence many are clinically apparent at birth. Pigmented lesions clinically resembling CMN have been reported to be present in 1–6% of neonates and the majority occur sporadically.39,231–235 The terms ‘tardive CMN’, ‘early onset nevi’, and ‘congenital nevus-like nevi’ have been used to represent nevi with clinical and histologic features of CMN that were not clinically apparent at birth but occurring often within the first 2–3 years of life.236

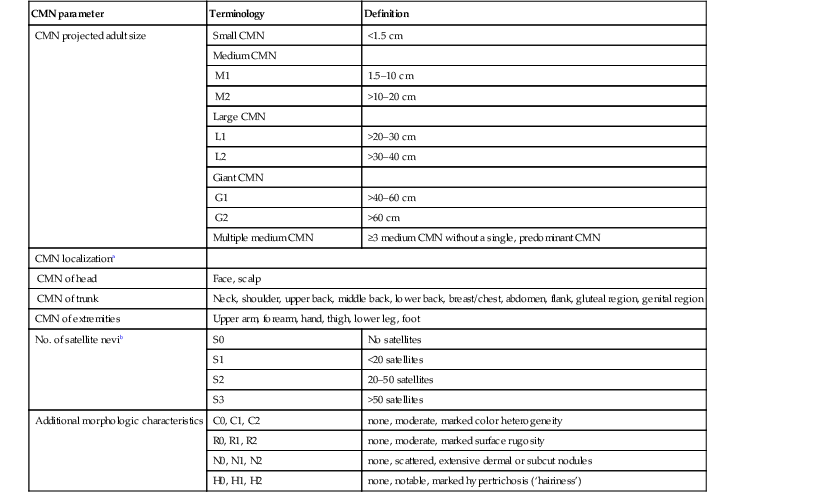

Historically, CMN have been classified according to their predicted largest diameter in adulthood (predicted adult diameter or PAS).237,238 The most commonly used classification designates small CMN as <1.5 cm, medium sized CMN between 1.5 and 19.9 cm, and large CMN ≥20 cm (Fig. 24.14). CMN measuring at least 50 cm in size are sometimes referred to as ‘giant nevi’. Although a nevus may on rare occasion grow disproportionately to the growth of the child during early infancy, most CMN will grow in proportion.239 A new, more detailed classification system (Table 24.6) has been proposed that may eventually help to better identify patients at greatest risk for developing melanoma and/or neurocutaneous melanocytosis. It also provides nomograms that can assist clinicians in easily predicting the final adult diameter of a nevus examined at any point during childhood.

TABLE 24.6

Proposed new classification of congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN)

| CMN parameter | Terminology | Definition |

| CMN projected adult size | Small CMN | <1.5 cm |

| Medium CMN | ||

| M1 | 1.5–10 cm | |

| M2 | >10–20 cm | |

| Large CMN | ||

| L1 | >20–30 cm | |

| L2 | >30–40 cm | |

| Giant CMN | ||

| G1 | >40–60 cm | |

| G2 | >60 cm | |

| Multiple medium CMN | ≥3 medium CMN without a single, predominant CMN | |

| CMN localizationa | ||

| CMN of head | Face, scalp | |

| CMN of trunk | Neck, shoulder, upper back, middle back, lower back, breast/chest, abdomen, flank, gluteal region, genital region | |

| CMN of extremities | Upper arm, forearm, hand, thigh, lower leg, foot | |

| No. of satellite nevib | S0 | No satellites |

| S1 | <20 satellites | |

| S2 | 20–50 satellites | |

| S3 | >50 satellites | |

| Additional morphologic characteristics | C0, C1, C2 | none, moderate, marked color heterogeneity |

| R0, R1, R2 | none, moderate, marked surface rugosity | |

| N0, N1, N2 | none, scattered, extensive dermal or subcut nodules | |

| H0, H1, H2 | none, notable, marked hypertrichosis (‘hairiness’) | |

a One or more of these localizations should be used to describe preponderant area of involvement.

b Refers to number of satellites within first year of life; in case this number is not available, actual number should be mentioned.

(Adapted from: Krengel S, Scope A, Dusza SW, Vonthein R, Marghoob AA. New recommendations for the categorization of cutaneous features of congenital melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 68(3):441–451.)

In general, CMN may be macules, patches, papules or plaques at birth. Coloration may be quite homogenous throughout or heterogeneous with shades of brown, black, red, or blue. The texture may be smooth, nodular or cobblestone-like and hair may or may not be present at birth and may or may not develop as the child ages and can be fine or coarse in texture when present. A cerebriform, or cutis verticis gyrata, appearance may be present in large scalp CMN. Neurotization and lipomatous changes are also features that can be seen, particularly in larger CMN. Atrophic CMN can also occur. Over time, CMN tend to evolve and may become darker or lighter, may become more or less heterogeneous in color and the surface texture may change. CMN can also develop superimposed nodules and papules. The CMN-involved skin can be xerotic and eczematous resulting is symptoms of pruritus. The dermoscopic pattern of most CMN found on the head/neck/trunk is globular and those found on the lower extremities tend to exhibit a reticular pattern.240

Making the diagnosis of a CMN is most often done by clinical appearance and dermoscopic features. The larger CMN can easily be diagnosed based solely on their size. For smaller CMN, their history of presence since birth, surface topography, presence of hypertrichosis or globular dermoscopic morphology can assist in diagnosis. When biopsied, the histological features of CMN are similar to those found in common acquired nevi which arise later in life; however, CMN tend have a greater cellularity with deeper extension of nevus cells into the deep dermis and subcutis and cells extend along adnexal structures such as hair follicles and around blood vessels and nerves.241 Depth of nevus cell infiltration tends to correlate with the size of CMN.242

Although most CMN occur sporadically, rare familial clustering of giant CMN has been observed.243,244 The concept of paradominant inheritance has been introduced as a possible explanation of the familial occurrence in an otherwise sporadic condition.

Small and medium congenital melanocytic nevi

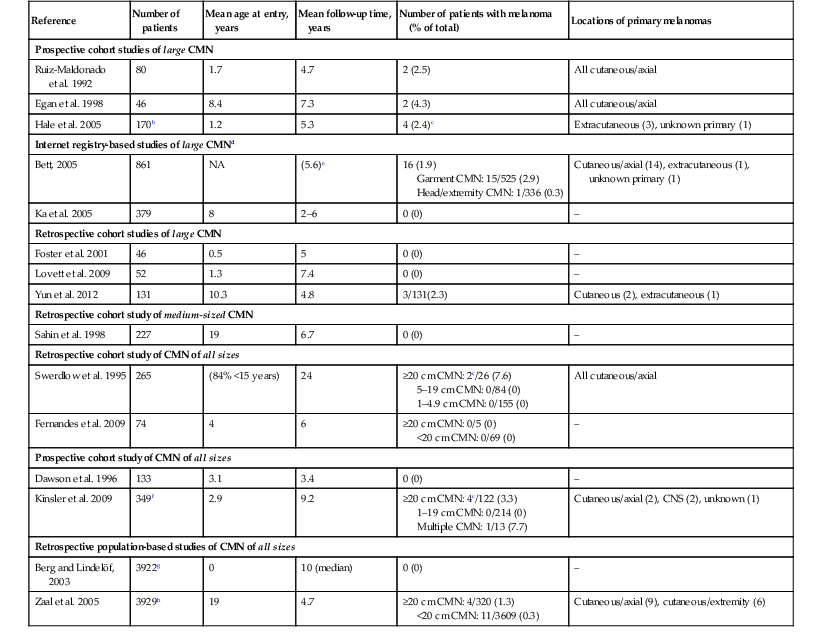

Small and medium CMN are often tan to brown in color and oval-shaped with well-demarcated borders (Fig. 24.15). Lesions may develop a mammillated surface and hypertrichosis over time (Figs 24.15, 24.16). The risk of melanoma development in small and medium CMN is thought to be less than 1% over a lifetime and these melanomas generally develop well after puberty (Table 24.7).245–259 Melanomas arising in small and medium CMN tend to develop at the dermoepidermal junction and at the peripheral or leading edge of the CMN, making them more readily recognized by patients and clinicians.260 Although rare prepubertal cases of melanoma arising in medium CMN have been described, no cases of melanoma in medium-sized CMN were described in four large prospective and retrospective studies with significant patient follow-up.253–255,257

TABLE 24.7

Studies of melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) (includes longitudinal studies of ≥40 patients with CMN followed for a mean of ≥3 years and published since 1990)a

| Reference | Number of patients | Mean age at entry, years | Mean follow-up time, years | Number of patients with melanoma (% of total) | Locations of primary melanomas |

| Prospective cohort studies of large CMN | |||||

| Ruiz-Maldonado et al. 1992 | 80 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 2 (2.5) | All cutaneous/axial |

| Egan et al. 1998 | 46 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 2 (4.3) | All cutaneous/axial |

| Hale et al. 2005 | 170b | 1.2 | 5.3 | 4 (2.4)c | Extracutaneous (3), unknown primary (1) |

| Internet registry-based studies of large CMNd | |||||

| Bett, 2005 | 861 | NA | (5.6)e | 16 (1.9) Garment CMN: 15/525 (2.9) Head/extremity CMN: 1/336 (0.3) |

Cutaneous/axial (14), extracutaneous (1), unknown primary (1) |

| Ka et al. 2005 | 379 | 8 | 2–6 | 0 (0) | – |

| Retrospective cohort studies of large CMN | |||||

| Foster et al. 2001 | 46 | 0.5 | 5 | 0 (0) | – |

| Lovett et al. 2009 | 52 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 0 (0) | – |

| Yun et al. 2012 | 131 | 10.3 | 4.8 | 3/131(2.3) | Cutaneous (2), extracutaneous (1) |

| Retrospective cohort study of medium-sized CMN | |||||

| Sahin et al. 1998 | 227 | 19 | 6.7 | 0 (0) | – |

| Retrospective cohort study of CMN of all sizes | |||||

| Swerdlow et al. 1995 | 265 | (84% <15 years) | 24 | ≥20 cm CMN: 2c/26 (7.6) 5–19 cm CMN: 0/84 (0) 1–4.9 cm CMN: 0/155 (0) |

All cutaneous/axial |

| Fernandes et al. 2009 | 74 | 4 | 6 | ≥20 cm CMN: 0/5 (0) <20 cm CMN: 0/69 (0) |

– |

| Prospective cohort study of CMN of all sizes | |||||

| Dawson et al. 1996 | 133 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 0 (0) | – |

| Kinsler et al. 2009 | 349f | 2.9 | 9.2 | ≥20 cm CMN: 4c/122 (3.3) 1–19 cm CMN: 0/214 (0) Multiple CMN: 1/13 (7.7) |

Cutaneous/axial (2), CNS (2), unknown (1) |

| Retrospective population-based studies of CMN of all sizes | |||||

| Berg and Lindelöf, 2003 | 3922g | 0 | 10 (median) | 0 (0) | – |

| Zaal et al. 2005 | 3929h | 19 | 4.7 | ≥20 cm CMN: 4/320 (1.3) <20 cm CMN: 11/3609 (0.3) |

Cutaneous/axial (9), cutaneous/extremity (6) |

b Among 35 additional patients who were not followed prospectively, five developed melanoma (all within truncal CMN).

c All melanomas developed in association with CMN measuring >39 cm (Hale et al. 2005)247; >40 cm (Swerdlow et al. 1995)254; >60 cm (Kinsler et al. 2009).257

d Information obtained by voluntary report of members of support groups for patients with congenital melanocytic nevi (not confirmed by the physician/medical record).

e Melanomas diagnosed prior to entry into the registry were not excluded.

f Includes 48 patients who were not followed prospectively.

g Data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register and Swedish Cancer Register.

h Histologically proven CMN entered into a comprehensive pathology archive in the Netherlands.

NA, not available.

(Modified from: Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi-when to worry and how to treat: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2010; 28(3):293–302 and Schaffer JV, Price HN, Orlow SJ. Congenital melanocytic nevi. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al., eds. Cancer of the skin. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2011:255.)

Large congenital melanocytic nevi

Large CMN occur in 1 in 20 000 individuals and are obvious at birth, most commonly covering an aspect of the trunk and less common on the head, neck and extremities.93 Affected areas of large CMN have been designated as a ‘cape’, ‘bathing trunk’ or ‘garment’ CMN due to their distribution, respectively. Lesions may have irregular or geographic borders. In about 75% of cases, multiple small CMN will accompany the large CMN; these additional CMN noted at birth and which may gradually increase in number over time have been historically termed ‘satellite nevi’. These additional multiple CMN should be noted in both size and number as a larger number of satellite nevi have been correlated with neurological anomalies.