Chapter 23 Disorders in the puerperium

POSTPARTUM HAEMORRHAGE

Primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH)

Aetiology

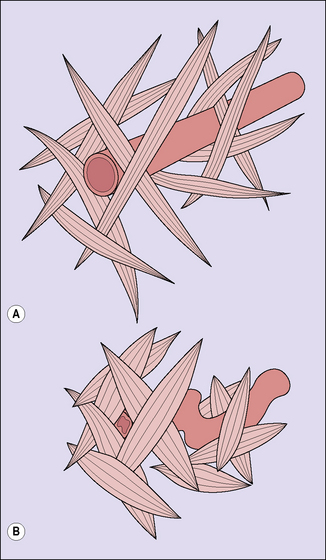

In normal labour, following the birth of the baby a blood loss of 200–600 mL occurs before myometrial retraction, supplemented by strong uterine contractions. This causes shortening and kinking of the uterine blood vessels and a retraction of the placental bed. These changes prevent further blood loss (Fig. 23.1). Some discussion arises as to whether this traditional quantity of blood loss is an underestimate, when blood loss is measured accurately. Provided the blood loss is less than 800 mL, the woman should have no problems.

In 20% of cases the cause of bleeding is a laceration of the genital tract, usually of the vagina or cervix, but rarely following uterine rupture (see p. 180). In a few instances PPH follows a blood coagulation defect, such as may occur following abruptio placentae.

Management

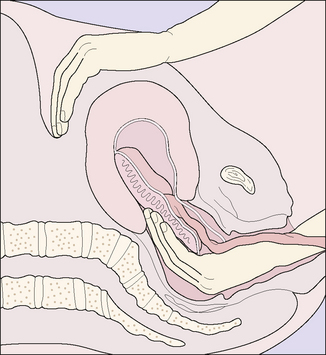

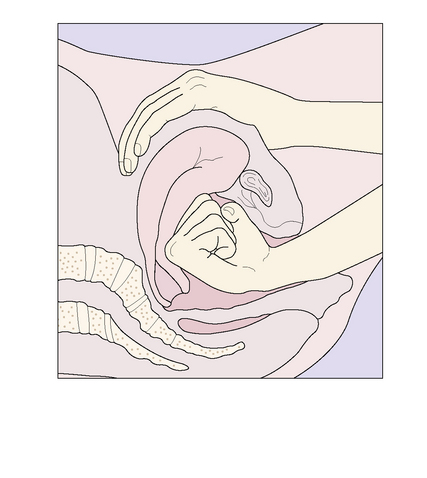

Third-stage bleeding (placenta in the uterus)

True postpartum haemorrhage (placenta expelled)

PUERPERAL INFECTION

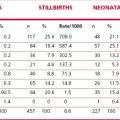

The infection may be genital or non-genital. The main causes and the probable infecting agent are shown in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 The main bacterial causes of infection in the puerperium

| Genital infection | % |

| Potential pathogens which normally inhabit the vagina: | |

| Anaerobic streptococci | 65–85 |

| Anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli | 5 |

| Haemolytic streptococci (other than group A) | 1 |

| Bacteria introduced from adjacent viscera: | |

| E. coli | 5–15 |

| Cl. welchii | Rare |

| Bacteria introduced from distant organs or from outside: | |

| Staphylococci | 5–15 |

| Streptococcus haemolyticus (group A) | 3 |

| Mycoplasma hominis | Rare |

| Non-genital infection | |

| Urinary tract infection:

Breast infection: |

THROMBOEMBOLISM

Thrombosis of a vein may occur in pregnancy (see p. 125) or, more commonly, in the puerperium, usually between days 5 and 15 of the puerperium. With better obstetric care and early ambulation, fewer women nowadays develop thromboembolic disorders in the puerperium. The incidence is fewer than 1 per 1000 births. The condition is more likely to occur in women who are overweight, over the age of 35, or who have had a caesarean section. Other risk factors include cardiac disease, diabetes and smoking. In 50 % an inherited or acquired thrombophilia can be identified.

POSTPARTUM PSYCHIATRIC PROBLEMS

Third-day blues

Between 50 and 70% of mothers experience a transient state of heightened emotional reactivity and feel either irritable, miserable or elated. Episodes of crying are common. The cause is not known. The symptoms start between the third and fifth days after the birth of the baby. The emotional lability usually lasts for less than a week, but may persist for a month. This is discussed on page 92.