Chapter 8 Diseases of the Vulva

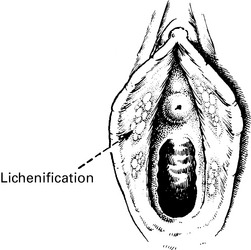

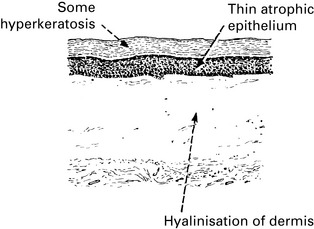

Vulval dermatoses

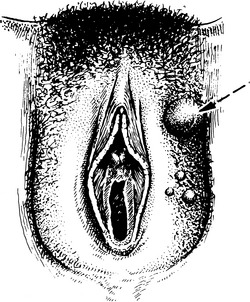

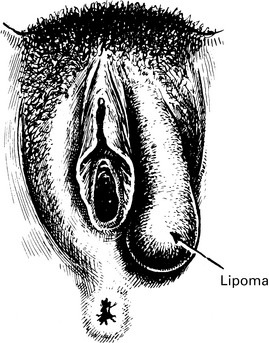

Benign tumours of the vulva

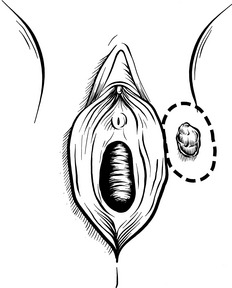

Cyst of Bartholin’s gland This is the commonest simple tumour of the vulva. Caused by obstruction of the duct, the cyst often becomes infected and requires surgical treatment (see p. 133).

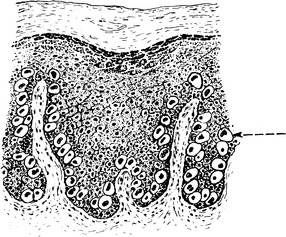

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

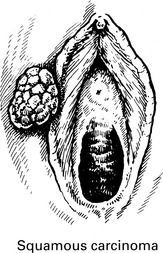

Carcinoma of the vulva

Vulval cancer is very rare in young women.

Aetiology

The aetiology of squamous vulval cancer is related to the underlying vulval skin disorder.

Clinical features

Any lump on the vulva must be examined and if suspicious biopsied.

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Confined to vulva. |

| IA | Tumour 2 cm or less maximum diameter. Stromal invasion no greater than 1 mm. No nodal metastases. |

| IB | As for IA, but stromal invasion greater than 1 mm. |

| Stage II | Tumour of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower 1/3 urethra, lower 1/3 vagina, anus). Negative nodes. |

| Stage III | Tumour of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with positive inguino-femoral lymph nodes. |

| III A | (i) With 1 lymph node metastasis (≥5 mm), or (ii) 1–2 lymph node metastasis(es) (<5 mm). |

| III B | (i) With 2 or more lymph node metastases (≥5 mm), or (ii) 3 or more lymph node metastases (b5 mm). |

| III C | With positive nodes with extracapsular spread. |

| Stage IV A | Tumour invades any of the following: (i) upper urethral and/or vaginal mucosa, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or fixed to pelvic bone, or (ii) fixed or ulcerated inguino-femoral lymph nodes. |

| Stage IV B | Any distant metastasis, including pelvic lymph node. |

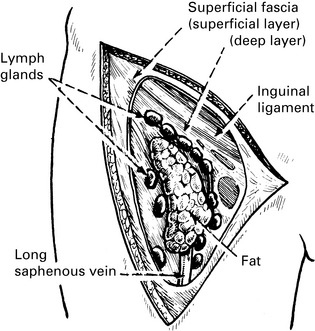

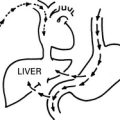

Lymphatic Spread

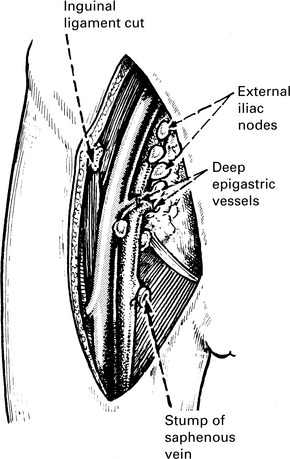

1. To the superficial inguinal glands which lie along the inguinal ligament and the saphenous vein (vertical group). These nodes lie between the layers of the superficial fascia in relation to numerous superficial vessels.

2. Then to the deep femoral nodes accompanying the femoral vessels, and from there to the external iliac, common iliac, and para-aortic glands.

3. This path is not invariably followed. The superficial nodes are occasionally bypassed. To detect aberrant pathways, techniques such as sentinel lymph node biopsy are being increasingly used. Using patent blue dye and radioactive tracer injection techniques, the primary drainage lymphatic pathway can be identified. This technique may also reduce the risk of lymphoedema.

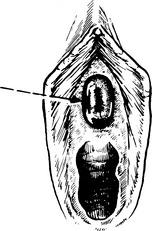

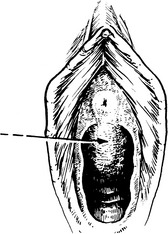

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the optimum treatment for vulval cancer.

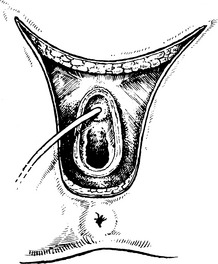

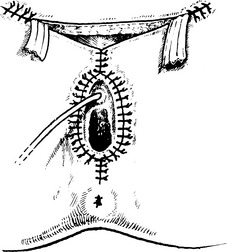

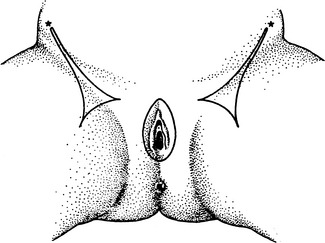

The whole vulva, skin and subcutaneous tissue are excised down to the periosteum.