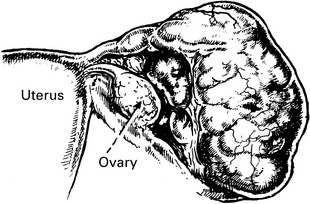

Chapter 13 Diseases of the Ovary and Fallopian Tube

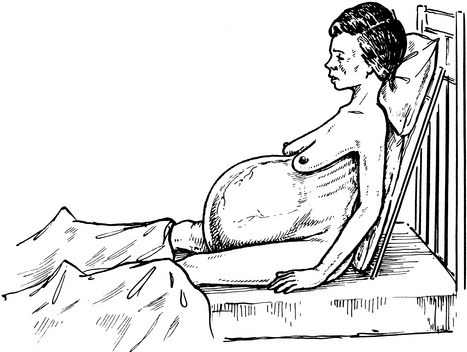

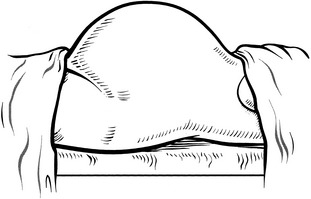

Clinical features of ovarian tumours

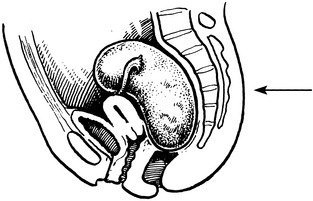

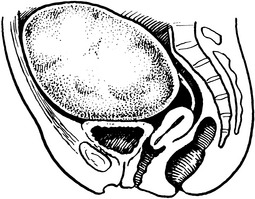

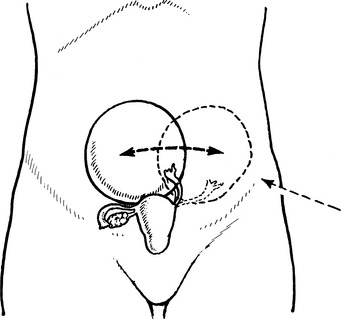

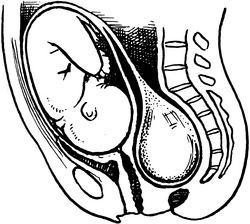

Differential diagnosis

Two very obvious mistakes must be avoided.

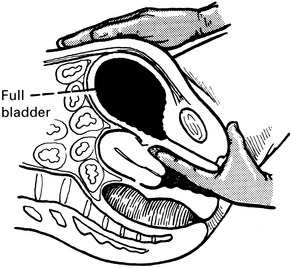

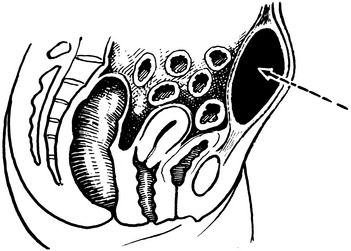

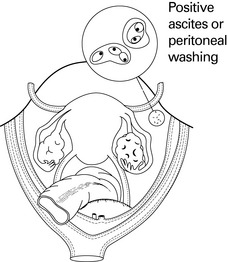

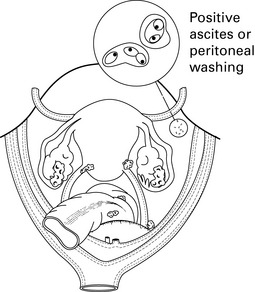

Ascites

(See ‘Shifting dullness’, page 77.)

Percussion note is dull over the top of the swelling and resonant in the flanks.

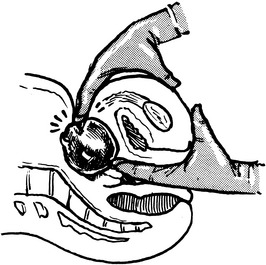

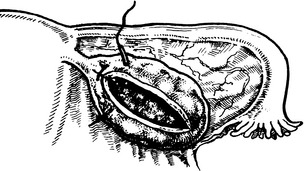

Ovarian cyst accidents

Differential diagnosis

‘Surgical conditions’ (i.e. those conditions commonly seen and dealt with by a general surgeon).

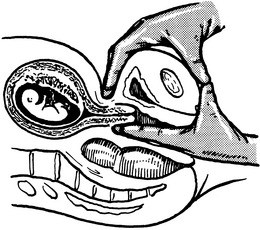

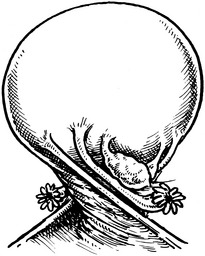

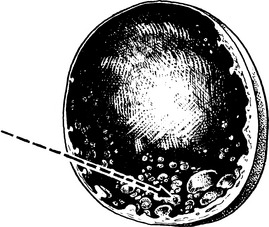

Rupture of ovarian cyst

Rupture may be either traumatic or spontaneous and may occur in the following conditions:

Benign and malignant ovarian tumours

Investigation

| Score | Menopausal status | Ultrasound |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Premenopausal | 1 abnormality |

| 3 | Postmenopausal | 2 or > abnormality |

Risk factors for ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer risk factors

| Increased | Decreased |

|---|---|

| Low parity | High parity |

| Infertility | Combined contraceptive pill |

| Endometriosis | Breastfeeding |

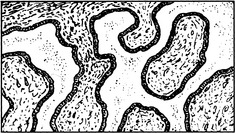

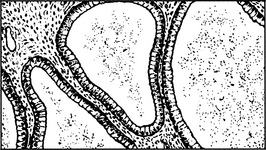

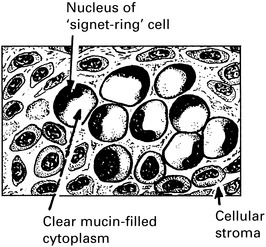

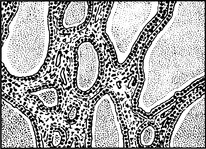

Epithelial ovarian tumours

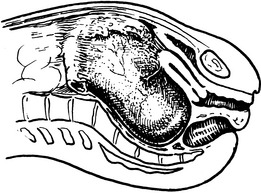

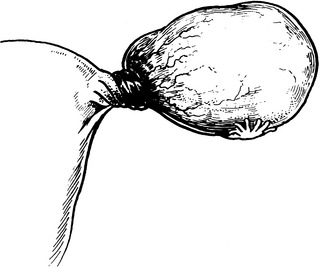

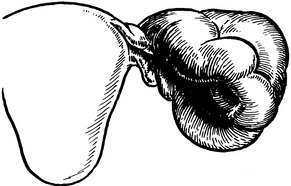

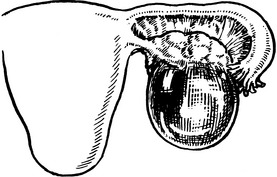

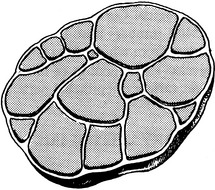

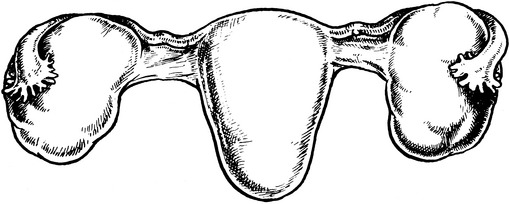

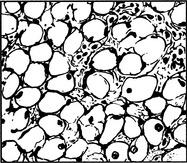

Serous cystadenoma

Germ cell ovarian tumours

| Undifferentiated | Dysgerminoma Gonadoblastoma |

| Differentiated | Embryonal Teratomas Extra-embryonal Yolk sac tumour Choriocarcinoma |

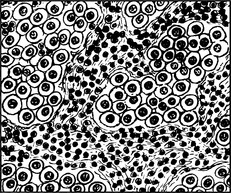

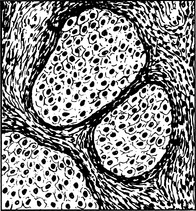

Germ cell ovarian tumours – undifferentiated

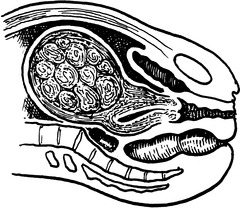

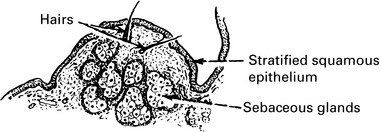

Teratomata

Hormone-producing tumours

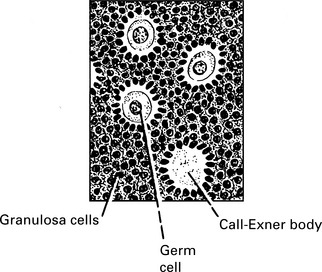

Oestrogen-producing tumours

Oestrogen excess can cause hyperplasia of:

In childhood there is accelerated skeletal growth and appearance of sex hair.

5% of these occur in children → precocious puberty.

60% occur in child-bearing years → irregular menstruation.

30% occur in postmenopausal women → postmenopausal bleeding.

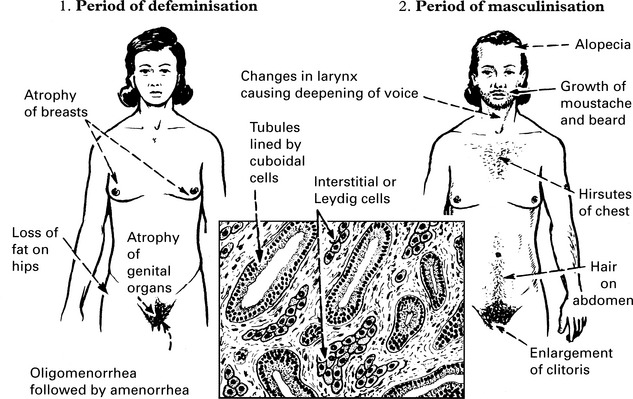

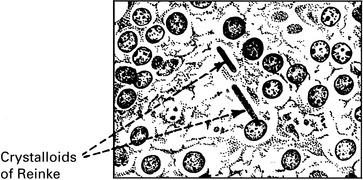

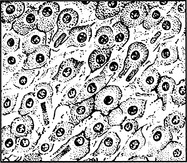

Other Hormone-Producing Tumours

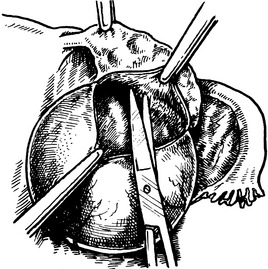

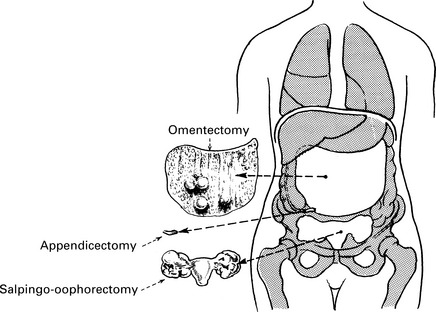

Treatment of ovarian cancer

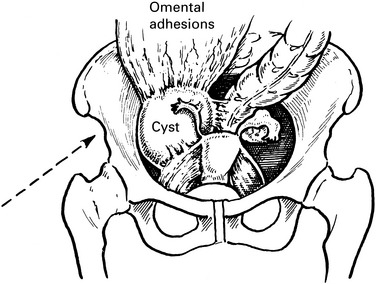

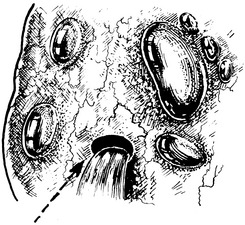

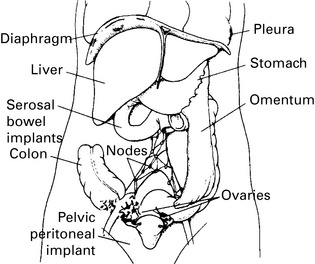

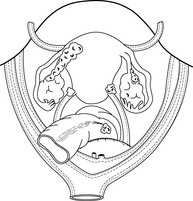

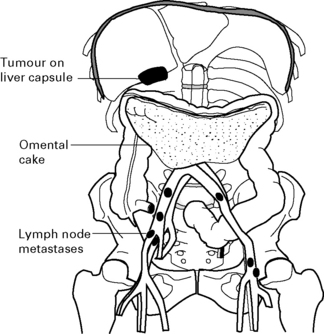

Spread of ovarian cancer

Spread directly into neighbouring structures – uterus, bladder or bowel.

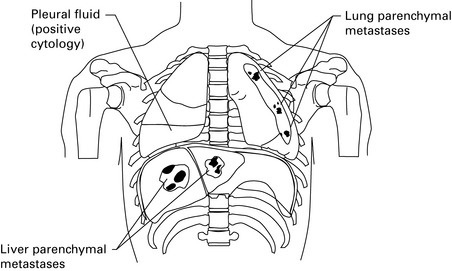

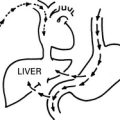

Blood spread is usually late and is to the liver and the lungs.

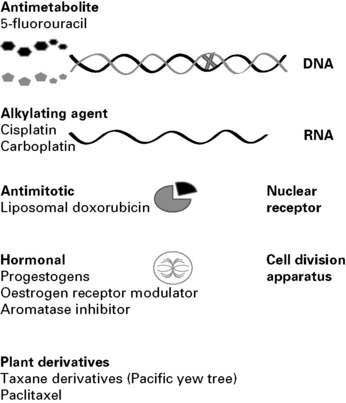

Chemotherapy is recommended for all stages of ovarian tumour greater than Stage 1B grade 2.

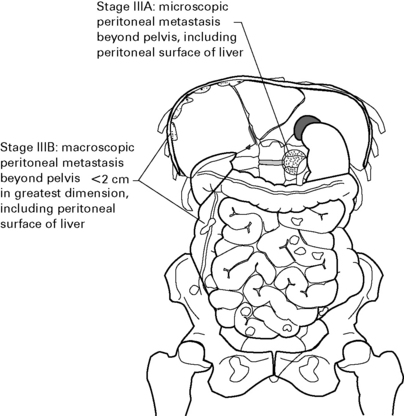

Staging of ovarian cancer

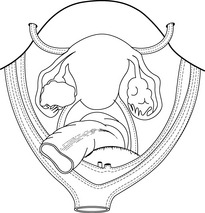

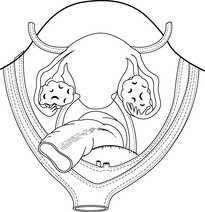

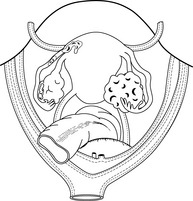

STAGE I Growth limited to ovaries.

IA. Limited to one ovary. No ascites.

IB. Limited to both ovaries. No ascites.

IIB. Spread to other pelvic tissues.

IIIC Abdominal implants >2 cm diameter or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes.

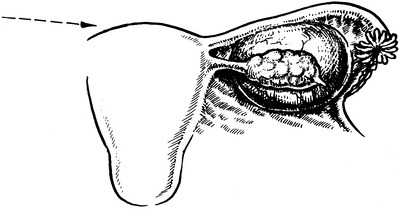

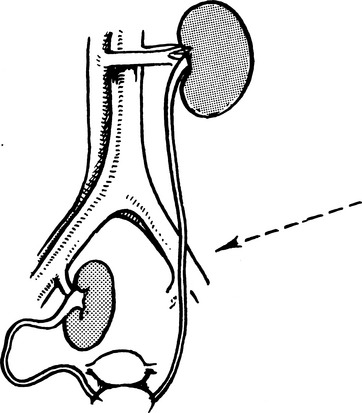

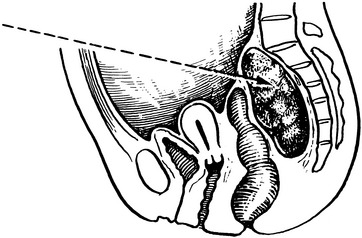

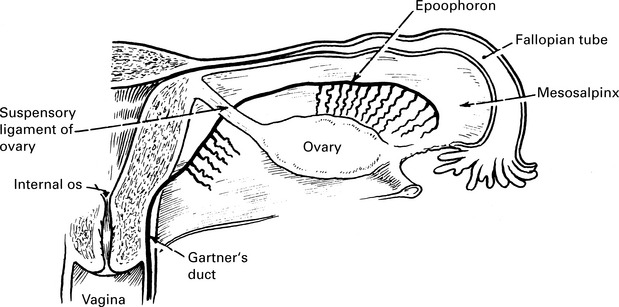

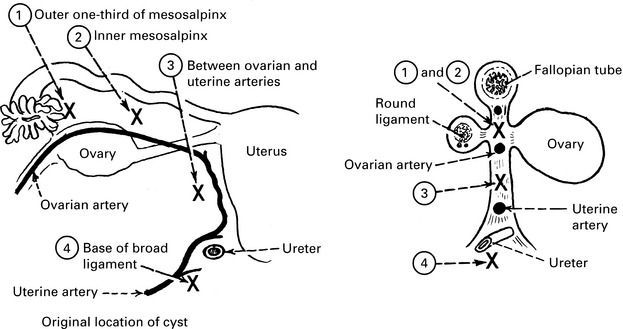

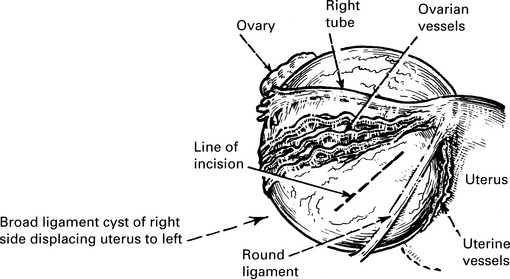

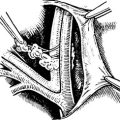

Broad ligament cysts

Carcinoma of fallopian tubes

Clinical staging

| Stage I | confined to one or both tubes |

| Stage II | pelvic extension |

| Stage III | spread to other structures (omentum, bowel, etc.), positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes or superficial liver metastases |

| Stage IV | distant metastases (including bladder), pleural effusion with positive cytology or parenchymal liver metastases |