Diseases of the Male Reproductive System

The male reproductive system develops in close relation with the urinary tract, and the two are usually thought of as the urogenital system. After formation of the metanephric duct and the induction of nephrons, a distal part of the meso-nephric (Wolffian) duct becomes integrated into the lateral walls of the urogenital sinus with separation into ureters and male ejaculatory channels. The testes develop from the gonadal ridge, and their seminiferous tubules combine with the secretory channels formed by the Wolffian duct. The prostate develops from epithelial invaginations in the distal urethra. Therefore, congenital diseases of the genital system may also be associated with disorders of the urinary tract. A summary of the many infectious and inflammatory diseases of the male reproductive system is shown in Table 7-1.

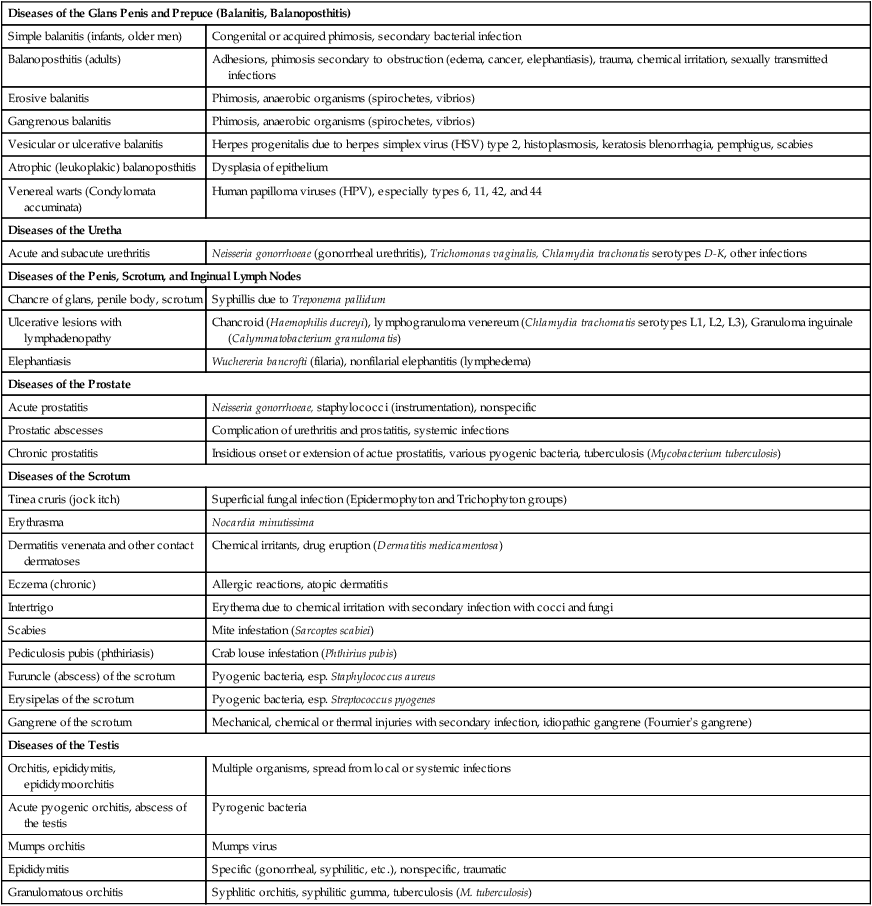

TABLE 7-1

INFECTIOUS AND INFLAMMATORY DISEASES OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

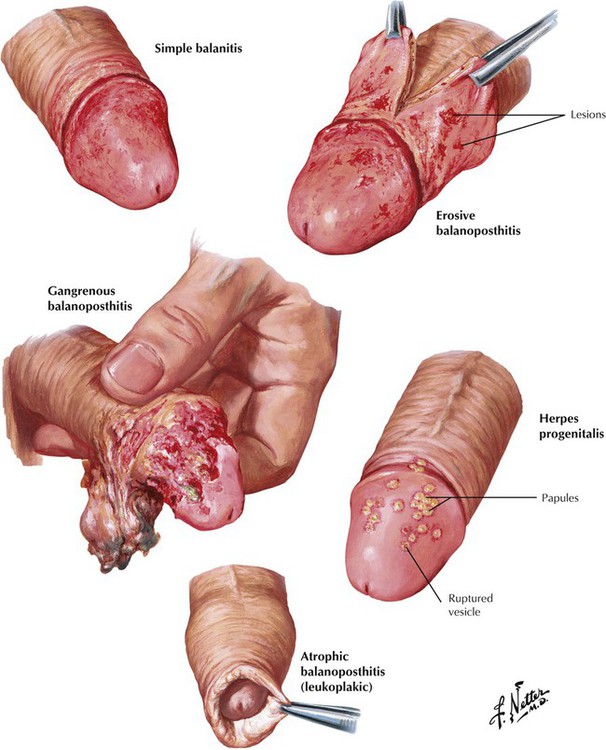

| Diseases of the Glans Penis and Prepuce (Balanitis, Balanoposthitis) | |

| Simple balanitis (infants, older men) | Congenital or acquired phimosis, secondary bacterial infection |

| Balanoposthitis (adults) | Adhesions, phimosis secondary to obstruction (edema, cancer, elephantiasis), trauma, chemical irritation, sexually transmitted infections |

| Erosive balanitis | Phimosis, anaerobic organisms (spirochetes, vibrios) |

| Gangrenous balanitis | Phimosis, anaerobic organisms (spirochetes, vibrios) |

| Vesicular or ulcerative balanitis | Herpes progenitalis due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2, histoplasmosis, keratosis blenorrhagia, pemphigus, scabies |

| Atrophic (leukoplakic) balanoposthitis | Dysplasia of epithelium |

| Venereal warts (Condylomata accuminata) | Human papilloma viruses (HPV), especially types 6, 11, 42, and 44 |

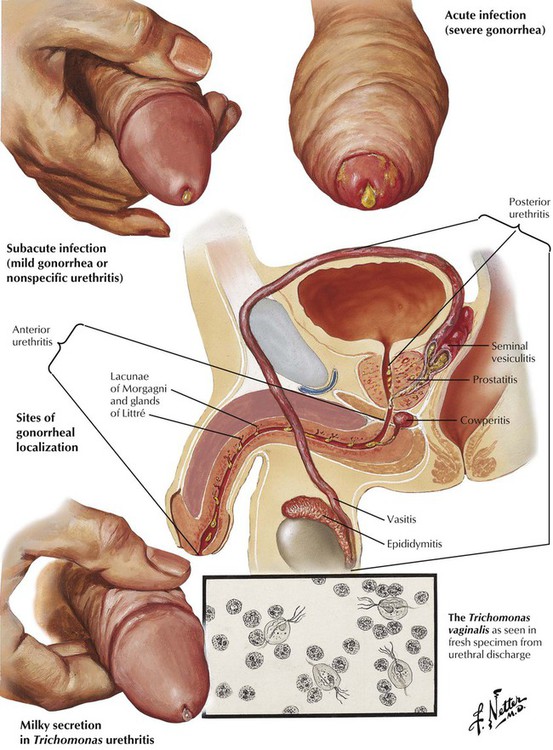

| Diseases of the Uretha | |

| Acute and subacute urethritis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrheal urethritis), Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachonatis serotypes D-K, other infections |

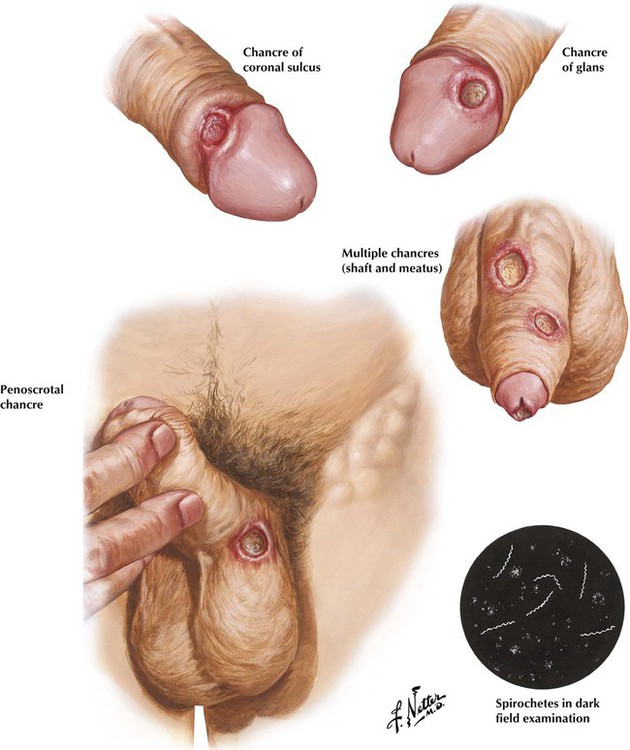

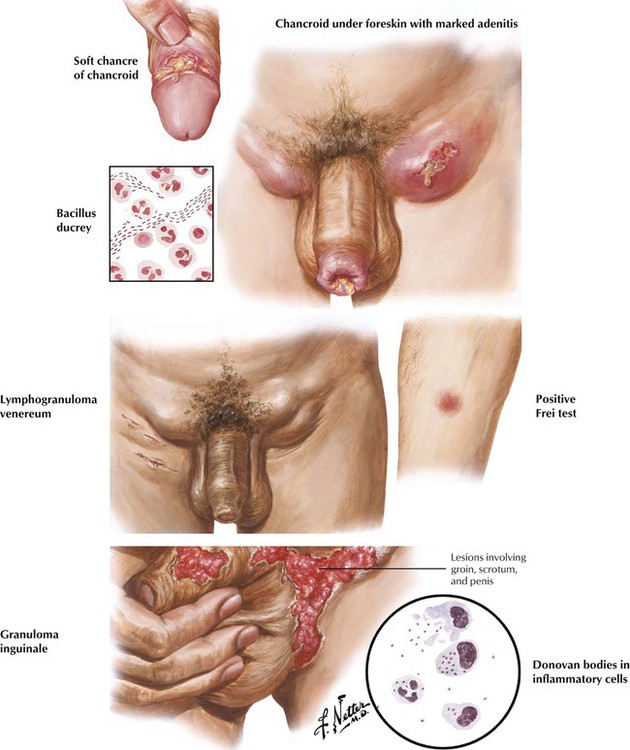

| Diseases of the Penis, Scrotum, and Inginual Lymph Nodes | |

| Chancre of glans, penile body, scrotum | Syphillis due to Treponema pallidum |

| Ulcerative lesions with lymphadenopathy | Chancroid (Haemophilis ducreyi), lymphogranuloma venereum (Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes L1, L2, L3), Granuloma inguinale (Calymmatobacterium granulomatis) |

| Elephantiasis | Wuchereria bancrofti (filaria), nonfilarial elephantitis (lymphedema) |

| Diseases of the Prostate | |

| Acute prostatitis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae, staphylococci (instrumentation), nonspecific |

| Prostatic abscesses | Complication of urethritis and prostatitis, systemic infections |

| Chronic prostatitis | Insidious onset or extension of actue prostatitis, various pyogenic bacteria, tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) |

| Diseases of the Scrotum | |

| Tinea cruris (jock itch) | Superficial fungal infection (Epidermophyton and Trichophyton groups) |

| Erythrasma | Nocardia minutissima |

| Dermatitis venenata and other contact dermatoses | Chemical irritants, drug eruption (Dermatitis medicamentosa) |

| Eczema (chronic) | Allergic reactions, atopic dermatitis |

| Intertrigo | Erythema due to chemical irritation with secondary infection with cocci and fungi |

| Scabies | Mite infestation (Sarcoptes scabiei) |

| Pediculosis pubis (phthiriasis) | Crab louse infestation (Phthirius pubis) |

| Furuncle (abscess) of the scrotum | Pyogenic bacteria, esp. Staphylococcus aureus |

| Erysipelas of the scrotum | Pyogenic bacteria, esp. Streptococcus pyogenes |

| Gangrene of the scrotum | Mechanical, chemical or thermal injuries with secondary infection, idiopathic gangrene (Fournier’s gangrene) |

| Diseases of the Testis | |

| Orchitis, epididymitis, epididymoorchitis | Multiple organisms, spread from local or systemic infections |

| Acute pyogenic orchitis, abscess of the testis | Pyrogenic bacteria |

| Mumps orchitis | Mumps virus |

| Epididymitis | Specific (gonorrheal, syphilitic, etc.), nonspecific, traumatic |

| Granulomatous orchitis | Syphlitic orchitis, syphilitic gumma, tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) |

Testicular Disorders

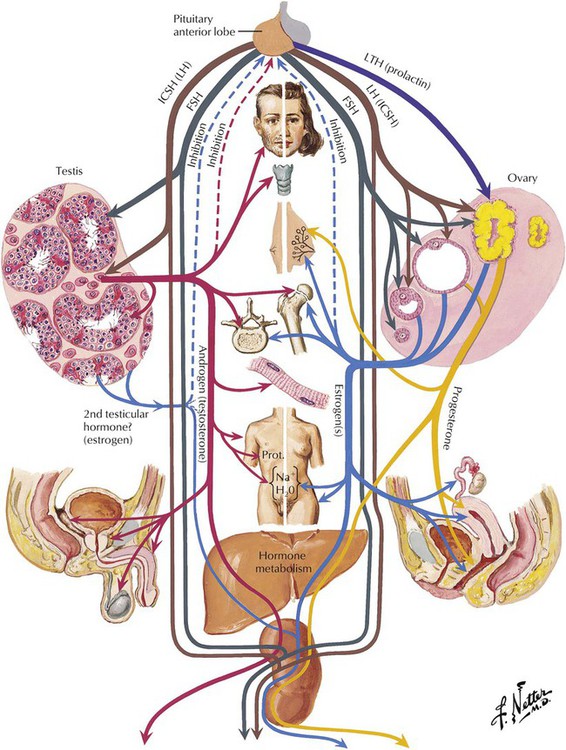

The 3 gonadotrophic hormones of the pituitary adenohypophysis are (1) follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH); (2) luteinizing hormone (LH) of the female, known as interstitial cell–stimulating hormone (ICSH) in the male; and (3) luteotropin (prolactin, LTH). These pituitary hormones determine the development of the male and female gonads. The germinal epithelia of the testes and ovaries are responsible for the production of sperm and ova, respectively. Various stromal cells of the gonads are responsible for the production of the androgen and estrogen hormones, which act on the organs of the reproductive tract, the secondary sex organs, and other parts of the body. There is a feedback loop for interdependent regulation of the production of the gonadal and pituitary hormones.

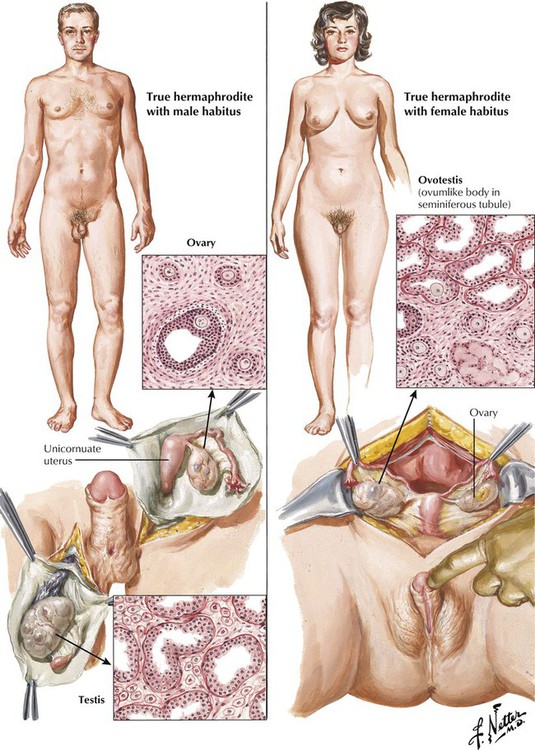

True hermaphroditism, defined as the presence of both testicular and ovarian tissue in the same patient, is rare. The chromosomal karyotype usually is euploid, with either a 46, XX or a 46, XY pattern, but may be aneuploid (45X/XY). Complex alterations in sex chromosomal gene expression lead to abnormal development of the gonads, including the formation of 1 or 2 ovotestes, an ovary on one side and a testis on the other, or a combination of these arrangements. The internal and external genitalia and secondary sexual characteristics correlate with the composition of the gonadal structures. Male pseudohermaphrodites have gonads with the histologic features of testes and varying degrees of feminine characteristics. Female pseudohermaphrodites have ovaries, but their external genitalia appear male. Male and female pseudohermaphroditism both generally result from a spectrum of neoplastic and nonneoplastic endocrine disorders.

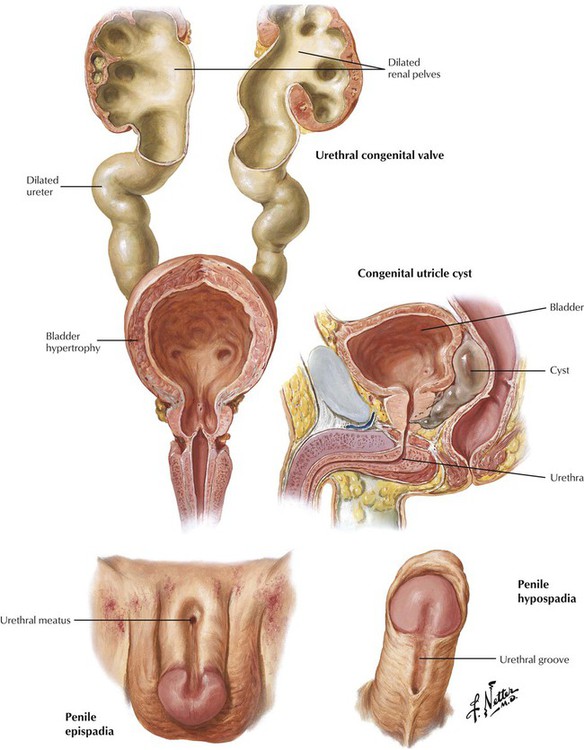

Certain congenital anomalies of the urinary bladder and urethra are clinically important. Congenital valves of the posterior urethra are thin folds of mucosa that develop in the prostatic urethra and extend from the verumontanum to the sides of the urethra. Obstruction to urine flow leads to bladder hypertrophy and dilatation, bilateral hydronephrosis, and, ultimately, fatal renal failure. Epispadia is a rare anomaly of the male urethra that involves the dorsum of the penis and can range from minimal deformity (glanular epispadia) to moderate deformity (penile epispadia) to complete epispadia. Hypospadia, which are more common, develop on the ventral aspect of the penis because of the failure of the genital folds to close fully and can be a component of pseudohermaphroditism. Epispadia and hypospadia are often associated with developmental anomalies of the urinary tract (extrophy of the urinary bladder, undescended testicles), infections, and sterility.

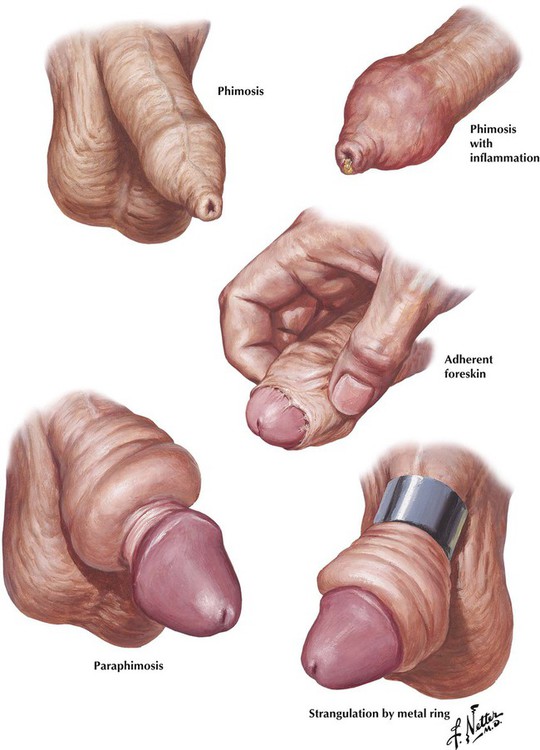

Phimosis is the presence of a redundant prepuce that cannot be retracted over the glans penis. If the condition is not relieved, fibrous adhesions may develop between the prepuce and the glans. Infection can significantly complicate the condition by producing an inflammatory exudate and edema. Paraphimosis is a retained retraction of a tight foreskin behind the coronary sulcus. Compression of the constricted veins and lymphatics leads to marked edematous swelling of the distal prepuce and glans. Strangulation may result from constriction of the penis by external devices, such as metal rings.

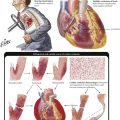

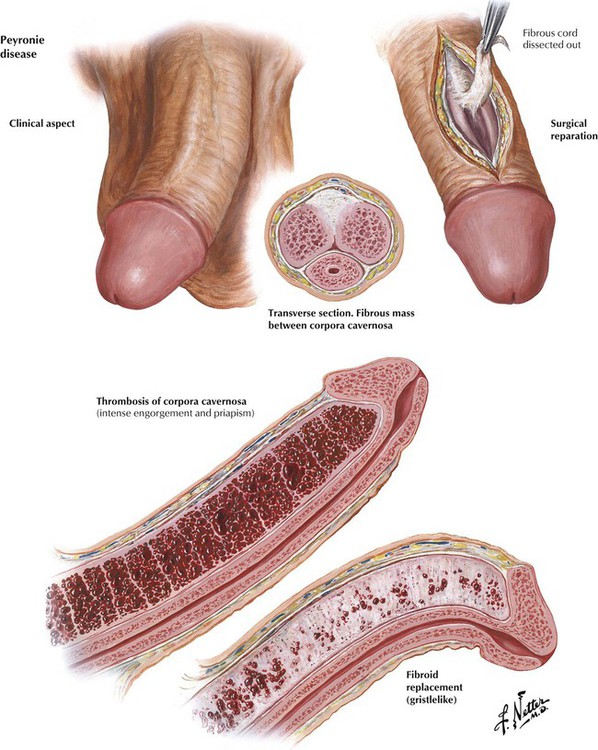

Peyronie disease (fibrous cavernitis, or plastic induration of the penis), a chronic, self-limiting disease of middle or older age, can be mistaken for malignancy. The position of the erect penis is distorted, and penile erection is painful because of the deposition of inelastic fibrous tissue (plaques) in the tunicae or intracavernous septum of the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Priapism, a painful and persistent erection of sudden onset, may be idiopathic or may occur in association with a systemic disorder, such as leukemia, gout, or sickle cell anemia, or with neoplastic or inflammatory lesions of the nervous system. True priapism is erection of the corpora cavernosa without erection of the glans penis or corpora spongiosum. A major complication of persistent erection is thrombosis of the corpora cavernosa. The organization of the thrombus into fibrous tissue leads to permanent impairment of penile erection.

Balanitis is inflammation of the glans penis. Balanoposthitis is a similar process involving the glans and the prepuce, usually associated with congenital or acquired phimosis, which predispose to growth of anaerobic microorganisms. Simple balanitis is a superficial infection presenting as a swollen, hyperemic, tender, and itchy lesion, whereas erosive balanoposthitis is characterized by the formation of painful necrotic erosive lesions. Gangrenous balanoposthitis is a rapidly progressive form of erosive balanoposthitis. In herpes progenitalis, which is caused by herpesvirus type 2, red papules on the glans penis develop into vesicles that rupture, leaving superficial ulcers. The lesions heal but tend to recur. Recurring episodes of any form of balanitis may lead to formation of thickened white epithelium, so-called atrophic (leukoplakic) balanoposthitis.

Urethritis results from infections with Neisseria gonorrhea, Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, or, less commonly, other microbes. In gonorrheal urethritis, a superficial infection of the urethral mucosa is followed by extension into the crypts and glands of the penile urethra, leading to involvement of the entire urethra, with an inflammatory exudate and purulent discharge in response to toxins released by the organisms. Complications include infections of the corpus spongiosum and posterior urethra, resulting respectively in painful erections and frequent, painful urination. Infection can extend from the prostate and posterior urethra down the spermatic cord to involve the epididymis. A rare complication is bacterial endocarditis due to gonococcal sepsis. Other forms of urethritis are usually more contained infections. Nonspecific urethritis can occur in isolation or with acute conjunctivitis and arthritis as Reiter syndrome.

The initial stage of syphilis is characterized by the development of a painless chancre, the hallmark primary lesion. The chancre, which usually develops slowly as an eroded papule, often accompanied by enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes, heals gradually over several weeks. Definitive diagnosis is made by detection of the Treponema pallidum organism by darkfield examination of fluid from the primary lesion or a lymph node because the serologic test results for syphilis are often negative during the initial phase of infection. In untreated cases, secondary syphilis quickly follows, with systemic dissemination of organisms and skin rash. After a latent period, tertiary syphilis develops, involving the cardiovascular system, the nervous system, or both.

Chancroid (soft chancre) usually develops on the penis as a result of venereal infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. The infection spreads to the inguinal lymph nodes, producing secondary infection, extensive necrosis, pain, and tenderness. Lymphogranuloma venereum is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes L1, L2, and L3, usually transferred during sexual intercourse. The small, inconspicuous vesicle or papule that typically develops on the glans penis is followed by inguinal lymphadenitis and perilymphadenitis, which often progress to a chronic, persistent infection, with suppuration of the inguinal lymph nodes, fistulae, and multiple skin abscesses. Syphilis, chancroid, and lymphogranuloma venereum can coexist. Granuloma inguinale is a chronic disease of the genitalia characterized by ulcer formation. Prevalent in the tropics, this disease is not necessarily of venereal origin. The lesion, caused by Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, is recognizable as Donovan bodies in inflammatory cells.

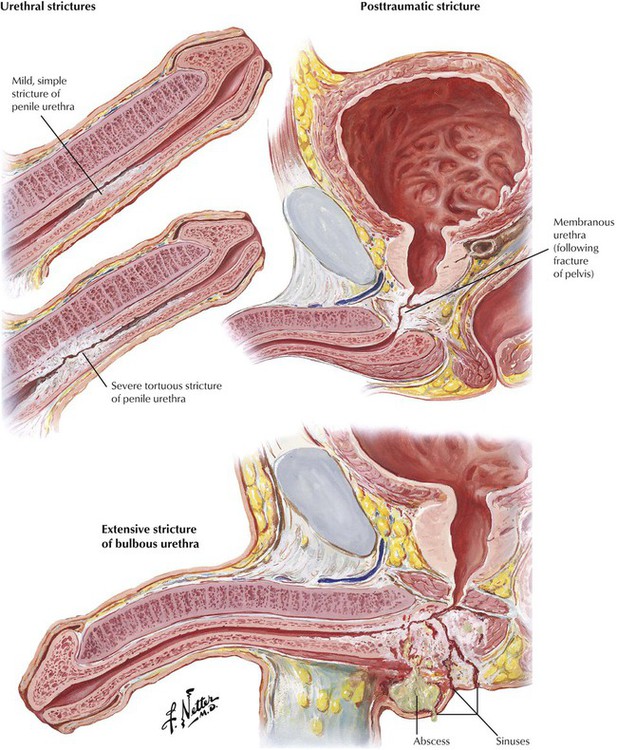

Strictures may involve any portion of the urethra, including the meatus and the penile, bulbous, membranous, and prostatic urethra. Narrowing in the urethral lumen may be long or short, single or multiple, and slight or severe. Strictures may develop after urethritis as a result of venereal and other infections or secondary to indwelling urinary catheters. Posttraumatic strictures develop after severe blows, straddle injuries, and various punctures and tears related to instrumentation. Urethral strictures may be accompanied by infection elsewhere in the genitourinary tract, including prostatitis, epididymitis, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. Urethral abscess and urinary sinuses or fistulae are particularly serious complications. Symptoms include difficulty in urination, hematuria, and pyuria.

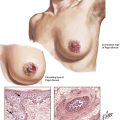

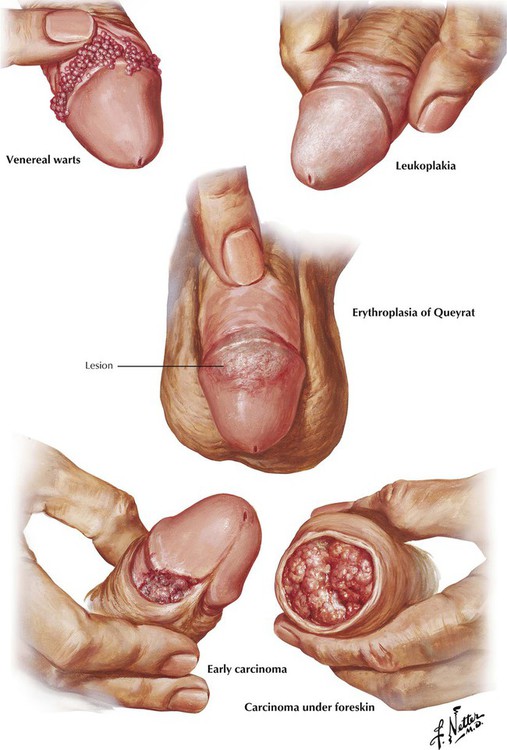

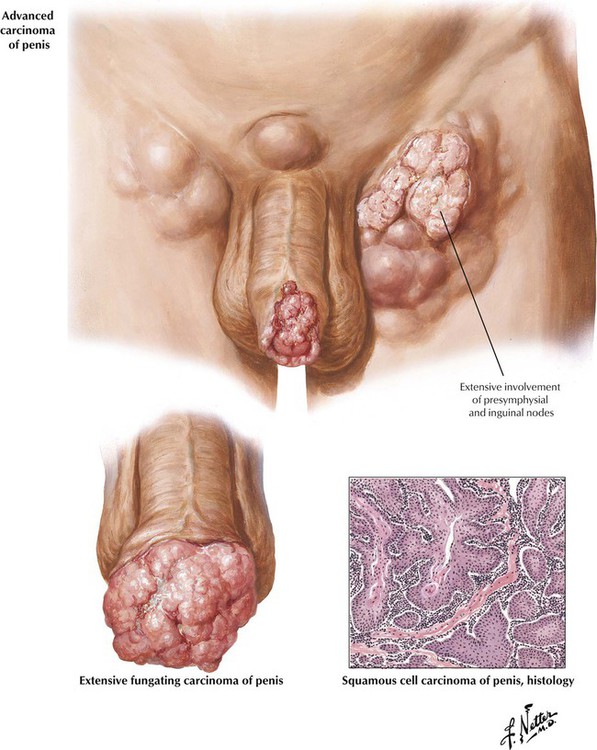

Venereal warts (condyloma acuminatum, verrucae) caused by human papillomaviruses (HPVs) usually occur around the base of the glans with a phimotic prepuce. Erythroplasia of Queyrat, a premalignant lesion of the glans penis, consists of slightly raised, red, velvety plaques composed of hypertrophied epidermis. Leukoplakia, a premalignant complication associated with chronic inflammation and glycosuria, can involve the entire prepuce or the glans. It develops as patches of indurated, leathery, blue-white skin. Early carcinoma of the penis starts as a small growth around the corona of the glans penis. The lesion often becomes ulcerated; untreated, it develops into a large fungating mass. Almost all penile cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). At least half of patients have nodal metastases at the time of presentation because the initial lesion is painless and may be obscured by a phimotic prepuce.

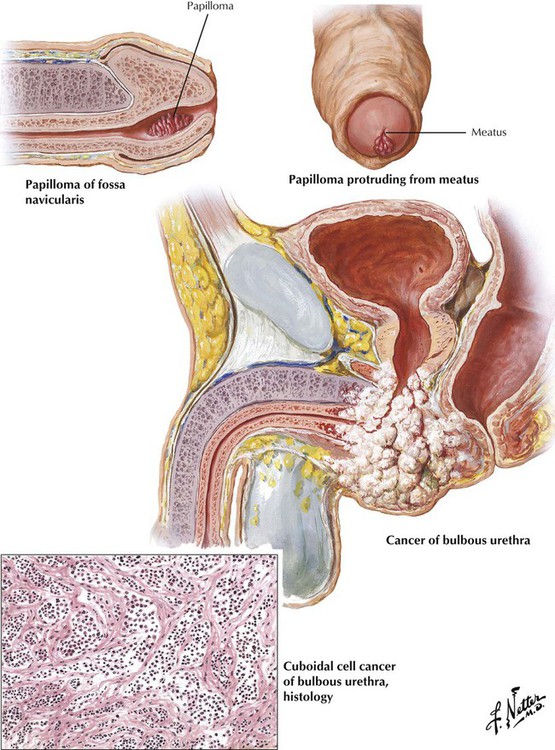

Papillomas (polyps) and verrucae (condylomas) are benign tumors of the urethra that usually develop just within the urethral meatus in the fossa navicularis as a result of inflammation in the urethral glands. They can cause urinary urgency, frequency and pain, hematuria, and disturbances in sexual function. Primary carcinoma of the urethra, a rare malignancy with an indolent course and an unfavorable prognosis, usually occurs in older men. The lesions develop equally often in the penile urethra and in more proximal portions of the urethra. Patients often present with a perineal abscess or a urethral stricture that is suspiciously increasing in size. Undetected tumors most commonly metastasize to regional inguinal lymph nodes.

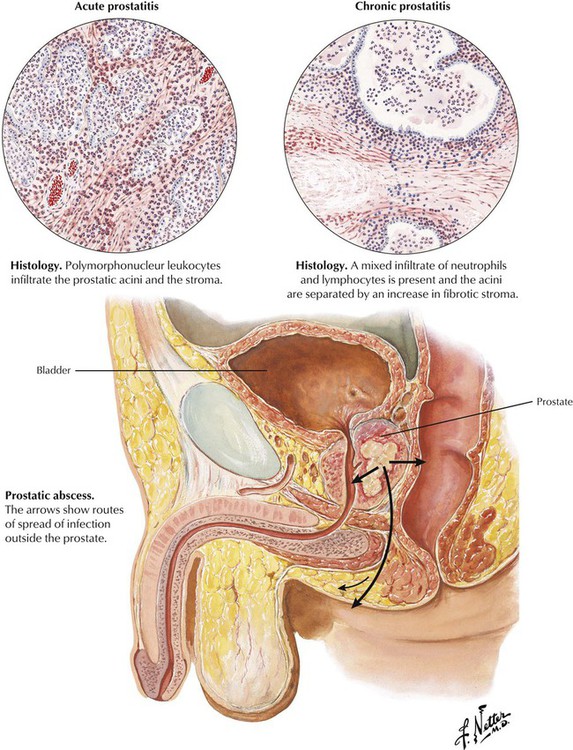

Acute prostatitis develops as an occasional complication of urinary tract instrumentation. The offending organisms are staphylococci or gram-negative bacilli; acute gonococcal prostatitis is uncommon in the antibiotic era. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes infiltrate the prostatic acini and the stroma. Prostatic abscess is a rare complication. Chronic prostatitis, with or without chronic seminal vesiculitis, usually develops without a history of an acute phase and presents as urinary or sexual dysfunction, sometimes with a thin, mucopurulent urethral discharge. Predisposing conditions include indwelling catheters, urinary tract instrumentation, urinary tract infection, spread of infection from distant foci, and prolonged sexual activity. There is a mixed neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate, and foci of fibrosis may develop. Although a mixed population of bacteria may be identified, lack of demonstrable bacteria is more common. Granulomatous lesions representing tuberculous prostatitis occur rarely.

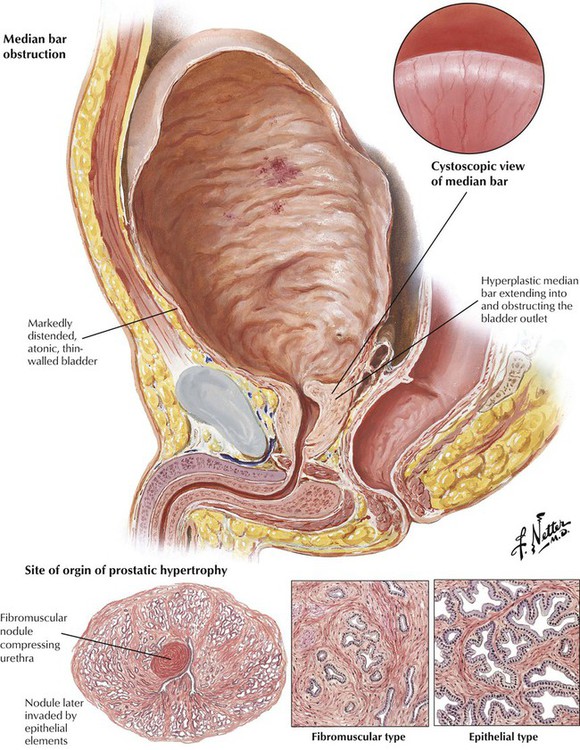

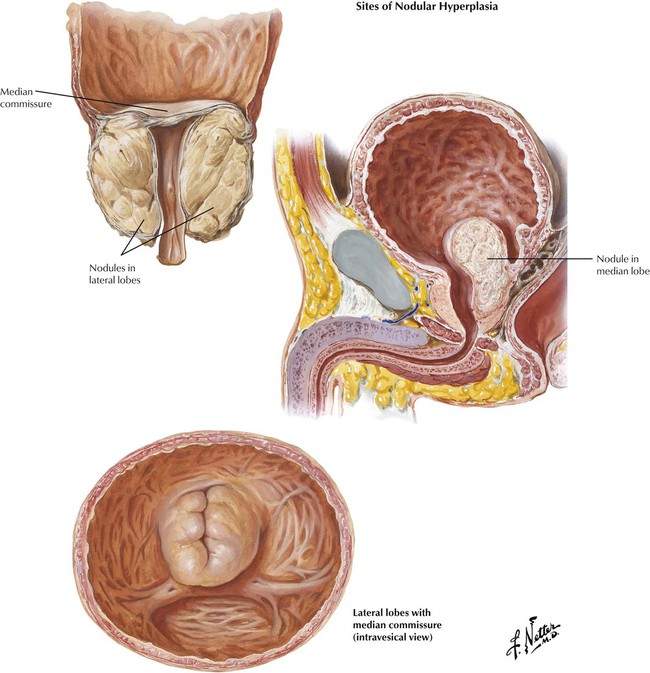

Nodular hyperplasia of the prostate is a disease associated with aging. Benign prostatic hypertrophy or hyperplasia (BPH) describes the benign proliferation (hyperplasia) of prostatic acinar epithelium and stroma with variable fibromuscular and epithelial predominance. Hyperplastic lesions typically arise in short glands adjacent to the proximal urethra in the middle lobe of the prostate (transitional zone). As the nodules increase in size, they compress the normal tissue of the more peripherally situated lateral and posterior lobes into a thin rim adjacent to the capsule. Formation of a median bar is one mechanism by which hyperplastic tissue obstructs the outlet of the urinary bladder. Significant BPH is confirmed by the detection of an enlarged, firm, rubbery prostate gland on rectal examination. BPH can adopt a number of gross configurations that obstruct the bladder outlet, including the median bar, the bilobular pattern (2 lateral lobes), and the trilobular pattern (2 lateral lobes plus median lobe). The pathogenesis of BPH involves hormonally driven proliferation and growth of prostatic tissue in the setting of androgen and estrogen imbalance. BPH leads to progressive urinary dysfunction, recurrent urinary tract infections, and obstructive uropathy. Surgical intervention is usually palliative if not curative.

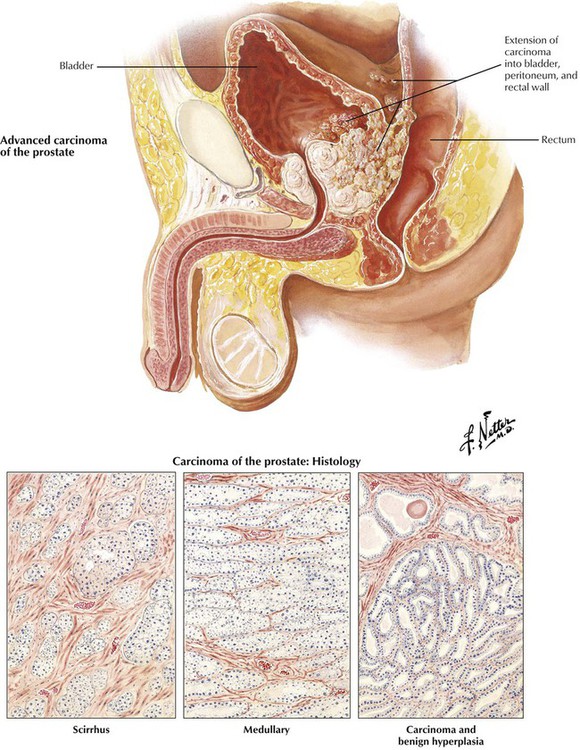

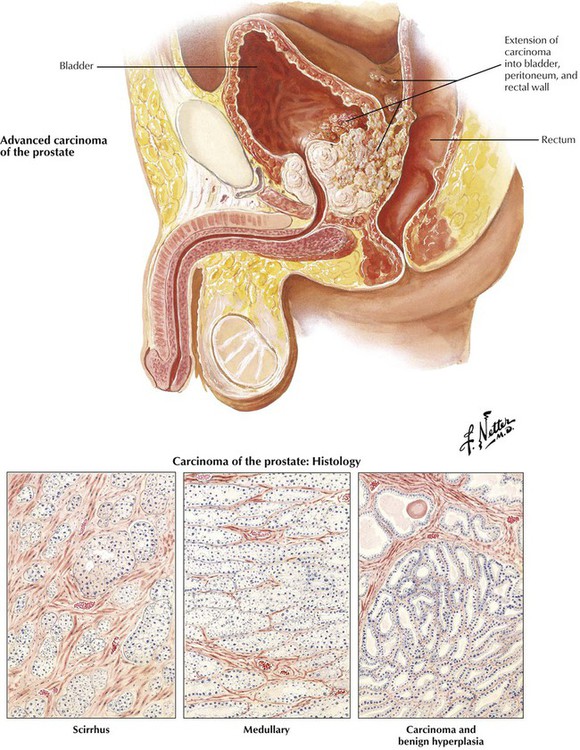

American men older than 50 years have a lifetime risk of clinical carcinoma of the prostate of approximately 10%. It occurs twice as frequently in African-Americans as in whites. This malignant tumor typically originates in the posterior lobe of the gland, with or without coexistent benign hyperplasia. Prostate cancer is frequently an adenocarcinoma composed of atypical epithelium (single cell layer without basal cells), which form small acini that grow in a crowded and disorganized pattern intermixed with abundant fibrous stroma (scirrhous form). Prostate cancer is scored on architecture by the Gleason scoring system. The unusual soft medullary type may elude early detection. Occult carcinomas are small lesions found incidentally at autopsy, in tissue resected for BPH, or in biopsy tissue for elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Other prostatic cancers grow progressively to infiltrate much of the parenchyma of the gland, including eventually the posterior capsule. Perineural invasion is probably important in local extension and development of metastases. Prostatic cancer extends initially by contiguous spread to the bladder and surrounding tissues. It spreads eventually to distant sites by invasion of the bloodstream and lymphatics. Approximately two thirds of patients with advanced disease have bony metastases. Typically, the metastatic foci stimulate bone growth, producing osteoblastic metastases that manifest as radiodense lesions, although radiolucent, osteoclastic metastases occur rarely. Lymph node and visceral metastases can be localized or widespread. Because androgens stimulate the growth of normal and neoplastic prostatic epithelium, carcinogenesis likely relates to an imbalance in production of androgens and estrogens. However, of utmost importance for cure of prostatic cancer is early detection and treatment before the malignancy has extended beyond the prostatic capsule to involve adjacent pelvic structures or spread to distant sites.

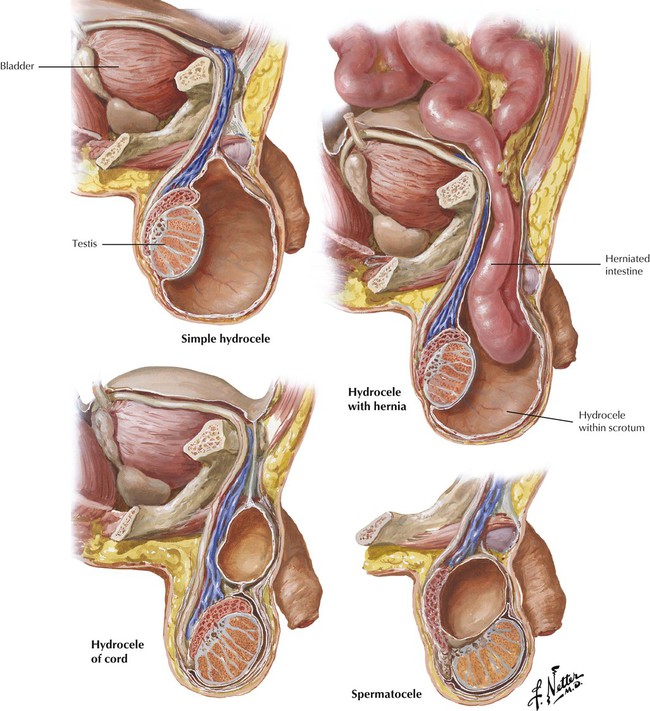

Hydrocele, an accumulation of serous fluid in the 2 peritoneal layers of the tunica vaginalis, results from abnormalities in the descent of the testicles from the retroperitoneal position in the abdominal cavity to the scrotum. The common simple hydrocele is a distended, fluid-filled segment of a normally formed tunica vaginalis. Congenital hydrocele, with or without hernia, involves a communication with the abdominal cavity. Hydrocele of the cord develops as a circumscribed sac of peritoneum localized in the cord. Acute hydrocele typically occurs secondary to trauma, tumors, or infection of the testicle and epididymis, particularly gonorrhea and tuberculosis. Chronic hydrocele may or may not have an apparent underlying cause. A spermatocele is a cyst within the scrotum that develops due to obstruction of the sperm transporting system. Rarely, enlargement of the spermatic cord is due to a malignant tumor, typically some type of sarcoma.

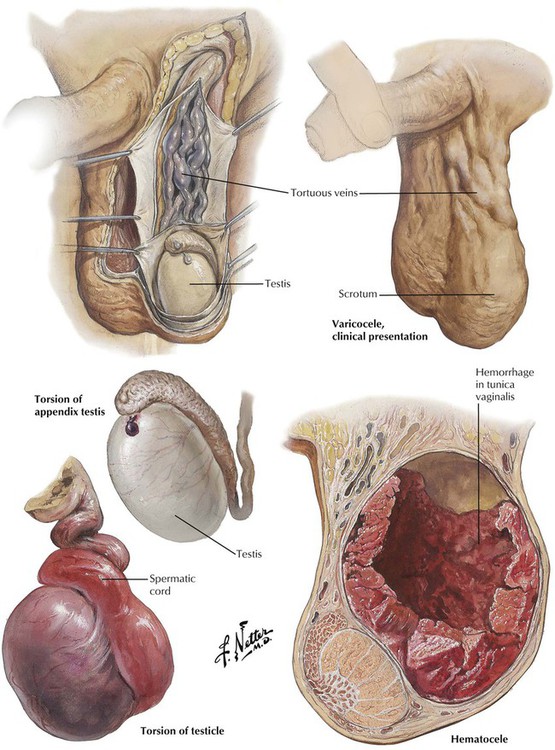

Varicocele, a collection of dilated, tortuous veins of the pampiniform plexus in the scrotum, is nearly always left sided and asymptomatic. Most varicoceles occur in young males and are without demonstrable etiology. The sudden onset of varicocele after the age of 30 years is secondary to retroperitoneal disease, such as tumors, hydronephrosis, or vascular anomalies. Hematocele is due to hemorrhage into the tunica vaginalis caused by an injury to the spermatic vessels, particularly trauma or operation, or it may occur spontaneously related to underlying vascular disease, infection, or neoplasm. Torsion (twisting) of the spermatic cord results in compression of the vasculature followed by infarction or complete gangrene of the testicle. Excessive mobility of the testis due to various developmental anomalies is the common predisposing factor. Torsion of the tiny vestigial appendix testis may cause acute pain in the scrotum, which can simulate acute epididymitis or can even mimic acute appendicitis from a referred pain pattern.

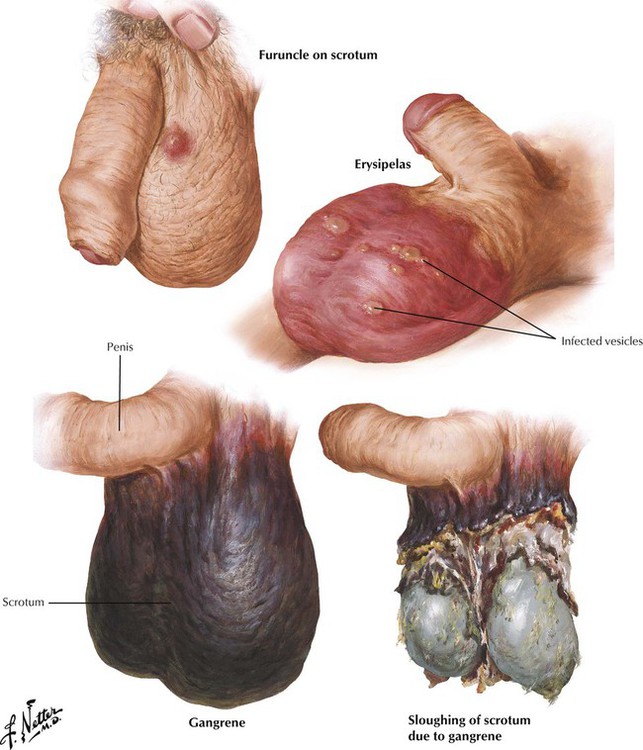

Reduced air circulation and evaporation of sweat in a tight space, irritation of scrotal skin by rubbing against adjacent structures, and ready access to bacteria are common causes of infection in the scrotum. Furuncles develop from hair follicles or sweat glands infected with Staphylococcus aureus. Scrotal erysipelas, a widespread superficial infection of scrotal skin, is usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Gangrene of the scrotum with extensive necrosis and sloughing of skin can develop as a result of extravasation of infected urine into the subcutaneous tissues or mechanical, chemical, or thermal injuries to the scrotum, particularly in individuals with diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, or other chronic diseases. Abrupt onset and rapid progression of gangrene in apparently healthy individuals are initiated by an occult infection (idiopathic or Fournier gangrene). Prompt debridement and antibiotic therapy are mandatory.

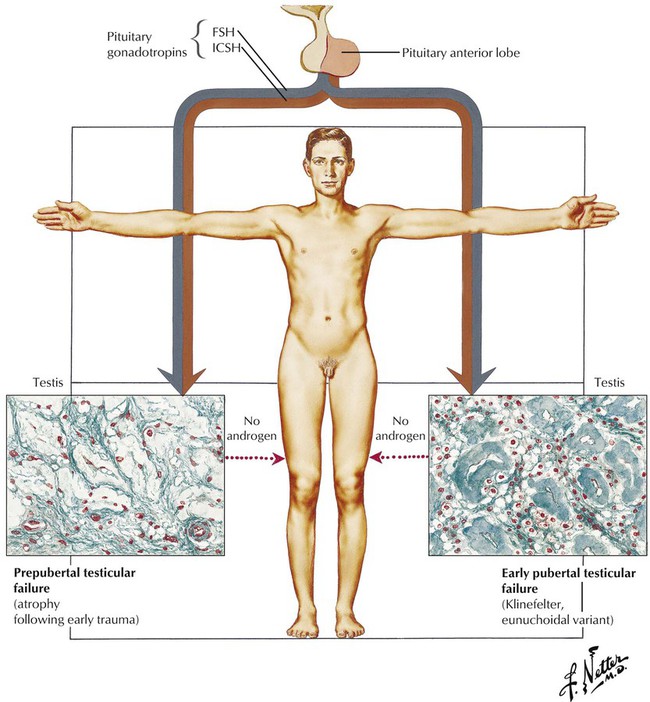

Hypogonadism connotes testicular deficiency in androgen production by the interstitial (Leydig) cells, although failure of the sperm-producing germinal cells is also involved. Eunuchism and eunuchoidism are, respectively, the absence of the testis and severe reduction of androgen production. Primary testicular failure, which typically begins in the prepubertal or very early pubertal period, is the result of various intrinsic developmental defects in the testis with intact pituitary function. This picture is characterized as primary or hypergonadotropic eunuchoidism or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Testicular atrophy also can occur from acquired causes, such as infections (e.g., mumps) and trauma. Klinefelter syndrome, a genetic disease with a sex chromosomal abnormality, usually XXY, presents at puberty with small testes with hyalinized seminiferous tubules and features of eunuchoidism.

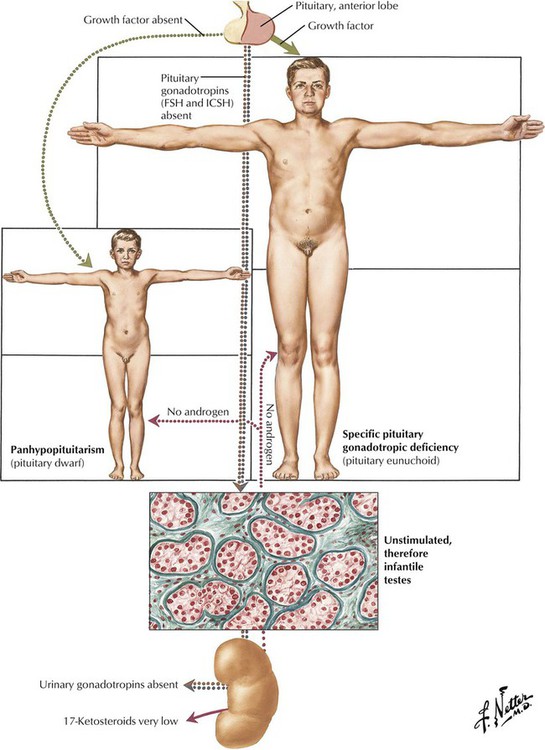

Testicular deficiency is secondary to failure of the pituitary to produce gonadotrophic hormones (secondary hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) in approximately 80% of hypogonadal male patients. Although the exact cause of the hypofunction is often unknown, it is important to rule out a pituitary tumor (chromophobe adenoma) or a hypothalamic tumor or other intracranial lesion. Histologically, the testis is immature, with small tubules containing undifferentiated spermatogonia and Sertoli cells and few interstitial Leydig cells. The phenotype may be eunuchoid with a specific pituitary gonadotrophic deficiency or that of a pituitary dwarf with panhypopituitarism. Many patients present with hybrid features of both primary and secondary hypogonadism.

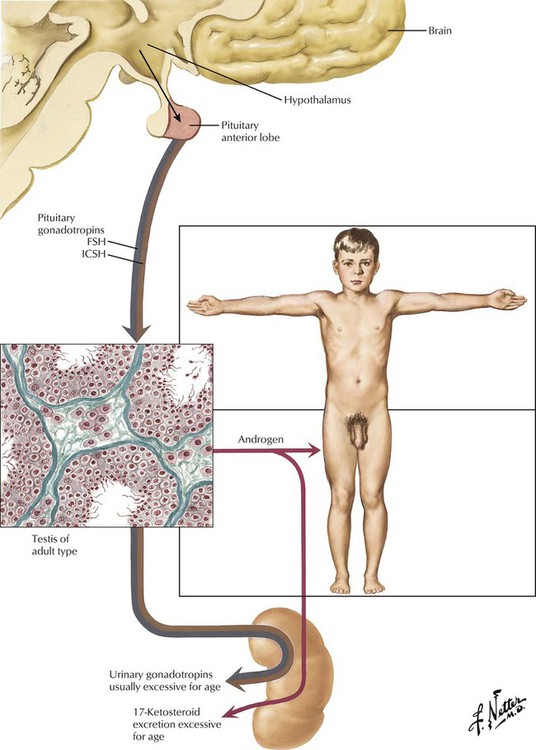

Sexual precocity involves not only premature enlargement of the penis, pubic hair, and testes (macrogenitosomia), but also growth of the skeleton, muscles, body hair, and other structures. Sexual precocity may result from premature development or abnormalities of the hypothalamus and pituitary. Histology of the testis shows a mature pattern with significant development of both tubules and interstitial cells. Urinary gonadotropins and 17-ketosteroids are usually excessive for age. The endocrine type (pseudosexual precocity) results from an adenoma, carcinoma, or hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex or an interstitial cell (Leydig cell) tumor of the testis. These patients can combine the macrogenitosomia and premature musculoskeletal development with Cushing syndrome, hypertension, or both. The testes remain infantile in both germinal and interstitial development.

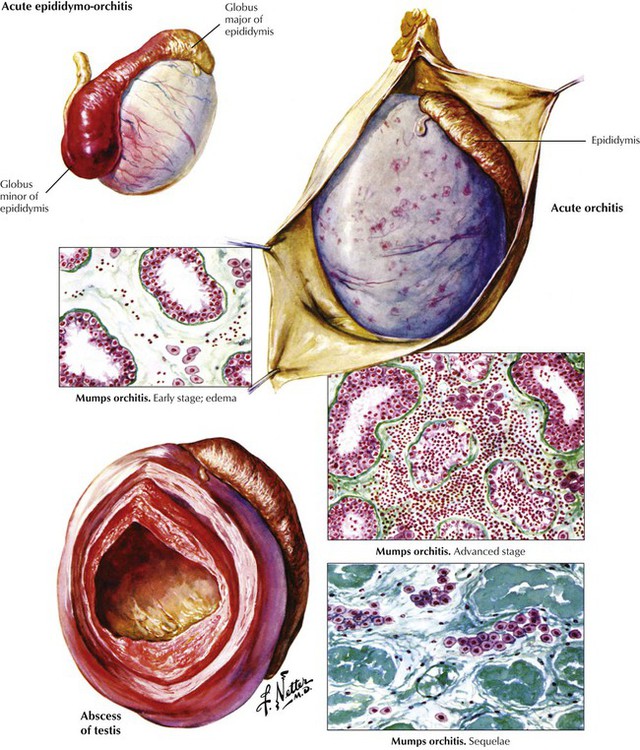

Orchitis may develop alone but more commonly occurs secondary to epididymitis. It may also result from systemic infections or be caused by bacterial toxins from distant localized infections, such as tonsillitis, sinusitis, or cellulitis. Acute pyogenic orchitis (epididymoorchitis) may progress to involve the testis, resulting in a large abscess. Mumps orchitis, which complicates approximately 20% of postpubertal mumps cases, progresses from transitory edema to marked interstitial inflammation (lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells). If severe, it can result in tubular sclerosis and testicular atrophy. Most cases are unilateral, and sterility is rare. Epididymitis without orchitis is common in adults. It may result from a specific infection (e.g., gonorrhea, syphilis, or tuberculosis), a nonspecific inflammation, or trauma. The source of organisms can be infected urine, prostate, or seminal vesicles, with spread via the vas deferens to the epididymis.

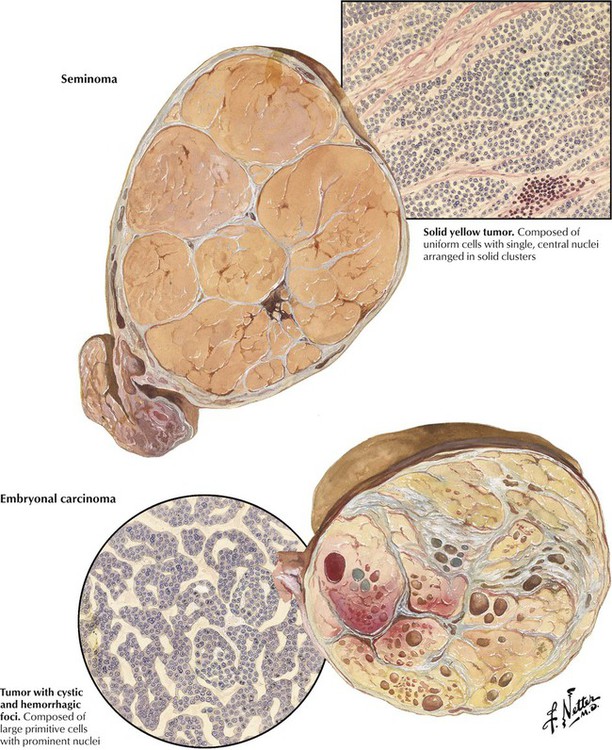

Malignant neoplasms of the testis, which usually occur in men aged 15-40 years, are more frequent in undescended testicles. Seminomas are nonencapsulated but well circumscribed tumors with a lobulated architecture and a yellow, orange, or pink color. Histologically, they are composed of uniform cells with single, prominent, central nuclei arranged in compact lobules separated by thin fibrous septa. The stroma typically contains lymphocytes and plasma cells. These tumors are highly radiosensitive and curable if they do not contain a malignant trophoblastic component. Embryonal carcinomas have foci of hemorrhage and necrosis in a yellow lobulated mass. Histologically, they are composed of primitive cells with prominent nuclei that grow in glandular, lobular, or tubular patterns and, occasionally, exhibit chorioepitheliomatous tissue. Embryonal carcinoma usually has relative radioresistant elements, may have spread beyond the testis at diagnosis, and carries a guarded prognosis.

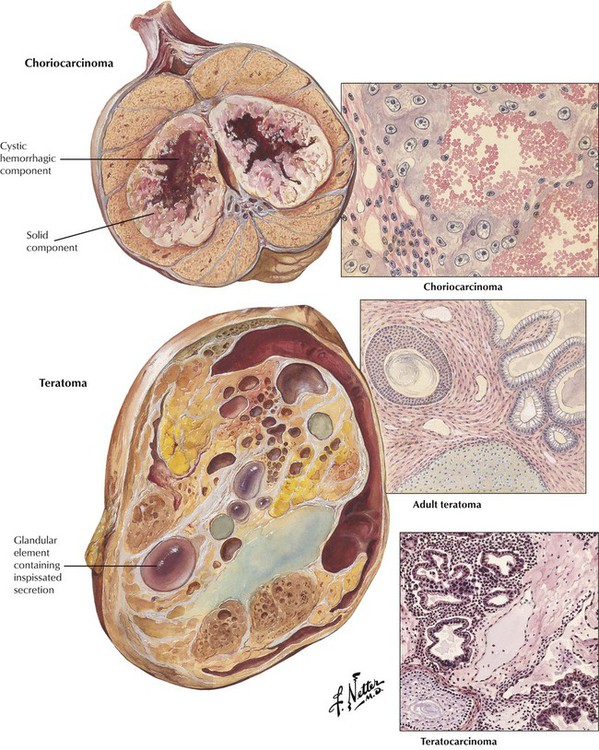

Choriocarcinomas are highly malignant neoplasms that occur most often as focal components of embryonal carcinomas and teratocarcinomas. They rarely occur as pure primary tumors. Histologically, choriocarcinomas consist of atypical syncytial and cytotrophoblastic cells surrounding blood spaces, which form structures resembling chorionic villi. Teratomas have a variable gross appearance with solid and cystic areas and a variable histologic appearance reproducing various mature glandular and solid tissues derived from the 3 germ layers. However, mature (adult) teratomas in males should be considered to have malignant potential because of the frequent occurrence of cryptic foci of poorly differentiated elements. Teratocarcinoma represents a group of tumors in which malignant elements of embryonal carcinoma, chorioepithelioma, and seminoma are present in conjunction with differentiated teratoid structures.