Diseases of the Female Reproductive System

Common diseases of the female reproductive system are discussed in the following chapter according to their anatomical sites. They comprise congenital alterations, inflammation, and infections (Table 8-1); benign and malignant tumors; and pregnancy-related disorders.

TABLE 8-1

INFECTIOUS AND INFLAMMATORY DISEASES OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

| Conditions | Causes |

| Dermatoses of the vulva | |

| Folliculitis and furunculosis | Staphylococcus aureus, mixed organisms |

| Herpes genitalis (progenitalis) | Herpes simplex virus type 2 |

| Intertrigo | Chafing plus dermatophytosis (fungal infection) |

| Tinea cruris | Ringworm of the groin, usually Epidermophyton floccosum |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Poxvirus |

| Psoriasis | Systemic noninfectious inflammatory disorder |

| Infections and other lesions of the vulva, vagina, and cervix | |

| Diabetic vulvitis | Mycotic (fungal) infection |

| Gonorrhea | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

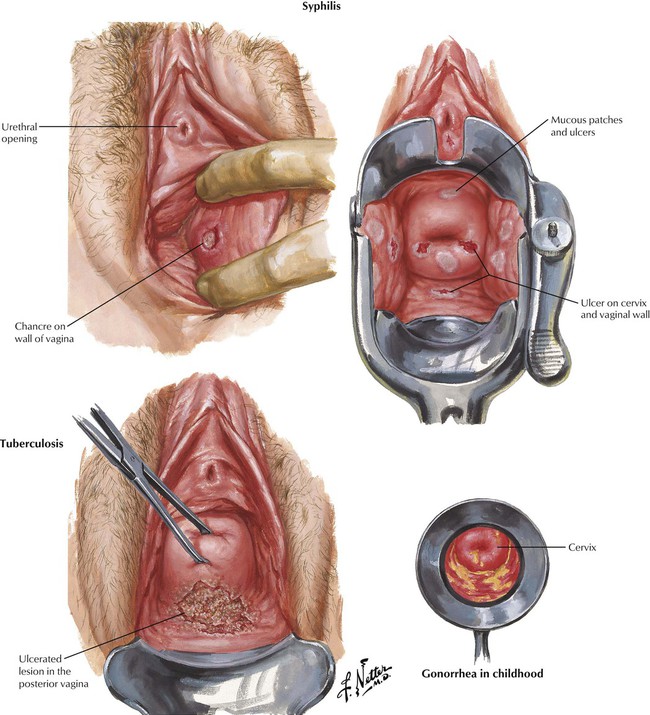

| Syphilis | Treponema pallidum |

| Chancroid | Haemophilus ducreyi |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Chlamydia trachomatis types L1, L2, L3 |

| Granuloma inguinale | Calymmatobacterium granulomatis (originally Donovania species) |

| Bartholin gland cyst and abscess | Neisseria gonorrhoeae, other pathogenic bacteria |

| Common vulvovaginitis, urethritis, and cervicovaginitis | Candida albicans (moniliasis), Chlamydia trachomatis (serotypes D-K), Trichomonas vaginalis, other organisms, including gram-positive and -negative bacteria (nonspecific vaginitis) |

| Genital (venereal) warts (condylomata acuminata) | Human papillomaviruses, especially types 6, 11, 42, and 44 (low risk for cervical cancer) |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

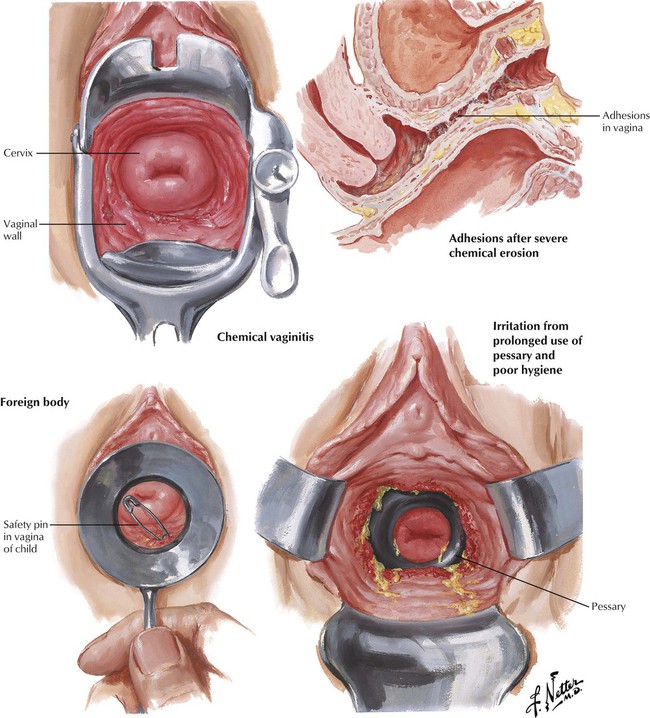

| Chemical vaginitis | Douches (high-concentration chemicals) |

| Traumatic vaginitis | Foreign bodies, pessaries |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | |

| Vulvitis, cervicitis, endometritis, salpingitis, oophoritis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, polymicrobial puerperal infections—staphylococci, streptococci, coliform bacteria, Clostridium perfringens |

| Puerperal infections | |

| Endometritis, vaginitis, sepsis | Streptococcus species, Staphylococcus species, gram-negative bacteria |

Diseases of the Uterus

The uterus is subdivided for diagnostic and therapeutic reasons into the uterine cervix, the endometrium, and the myometrium. Common diseases include functional disturbances, inflammation, and neoplasia. Cervicitis, which often results from sexually transmitted disease (STD), is common, whereas endometritis is rather rare. STDs include infections by papilloma virus, herpes simplex virus type II, syphilis, and gonorrhea (also see chapter 7). Chlamydia species cause infections of the female reproductive system with increasing frequency.

Pathology of the Mammary Gland

The skin of the vulva can be involved by the same spectrum of dermatoses that affect the skin of the rest of the body. Some common dermatoses are shown here, and the causes are listed in Table 8-1. Folliculitis is a papular or pustular inflammation involving the apertures of the hair follicles, and furuncles are larger and more deeply seated lesions with a central core of purulent exudate. Herpes genitalis or progenitalis is a recurring, localized condition, beginning as groups of vesicles on an edematous, erythematous base and subsequently forming small ulcers that dry, crust, and heal. Intertrigo and tinea cruris are superficial dermatoses associated with fungal infection. Vulvar lesions of psoriasis, a systemic noninfectious inflammatory disorder, are typically pruritic, red, and covered with silvery-white scales. The presence of similar lesions on the scalp and extensor surfaces of the extremities and nail changes help to establish the diagnosis.

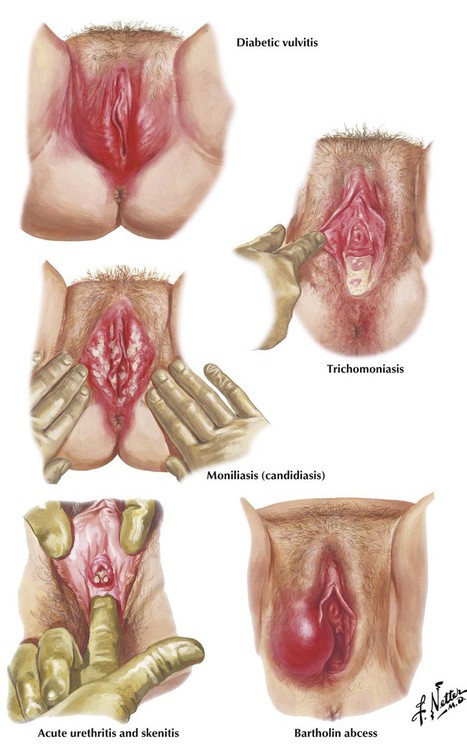

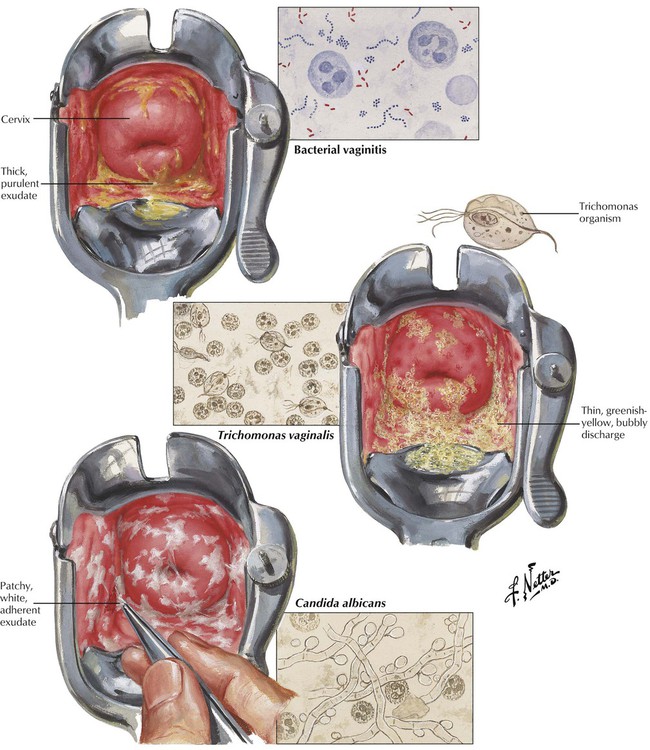

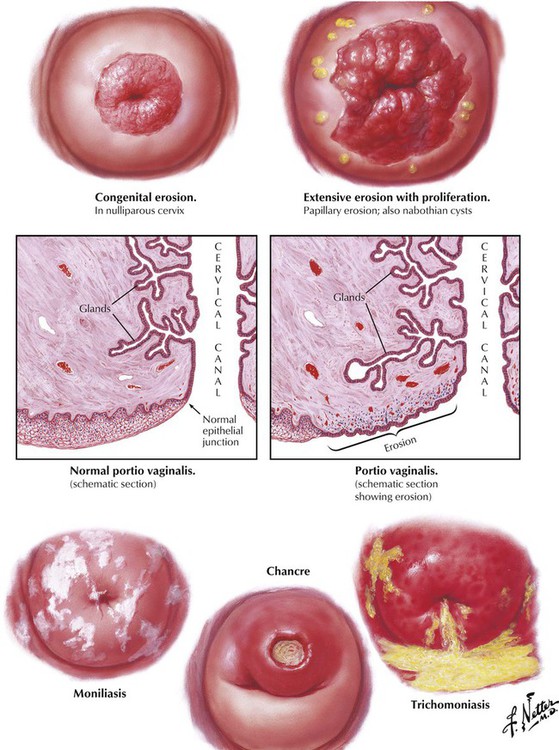

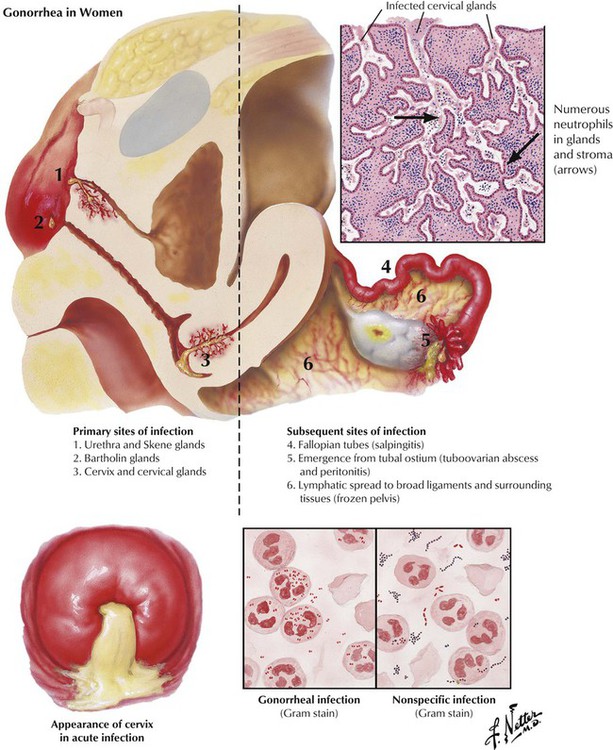

Presenting features of vulvitis or vulvovaginitis include pruritus vulvae, vaginal discharge, burning on urination, and dyspareunia. Diabetic vulvitis is characterized by an inflamed, dark-red or beefy appearance with a superimposed superficial fungal infection. The vulvovaginitis produced by Trichomonas vaginalis has a thick, odoriferous, bubbly discharge in the vestibule. Vulvovaginitis caused by Candida albicans and related yeast fungi (moniliasis) is characterized by white, cheesy, irregular plaques, partially adherent to the congested mucosa of the vagina and cervix (vaginal thrush). Acute gonorrhea often presents with vaginitis beginning 1 to several days after contact; occasionally, the disease may not manifest until after the following menses, when ascending infection has resulted in acute salpingitis. Examination of the external genitalia may reveal a congested vestibule with a purulent discharge and inflammation of the urethra, Skene ducts, and Bartholin ducts.

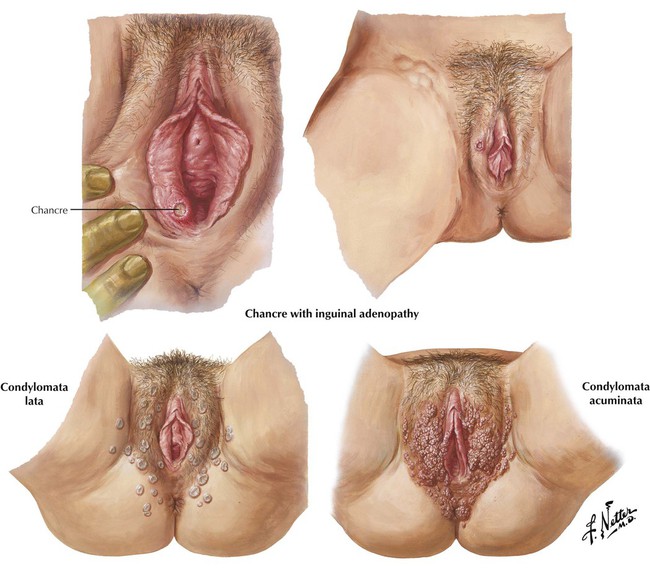

The painless ulcerated chancre, the primary lesion of syphilis, typically develops on the labia majora or vaginal mucosa approximately 3 to 4 weeks after infection and is easily overlooked. Inguinal lymphadenopathy develops slowly and is usually well demarcated 6 weeks after infection. Histologically, the chancre shows edema, congestion, and infiltration with lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid macrophages, and multinuclear giant cells. The diagnosis is made by the demonstration of the spirochetes of Treponema pallidum by dark field examination of wet preparations of the lesions. Condylomata lata, the lesions of secondary syphilis, are slightly elevated, disk-shaped papules with depressed centers. Condyloma acuminata (genital or venereal warts) are caused by an infection with HPVs, often not the precancerous 16 and 18. The confluent, cauliflowerlike growths of squamous epithelium form multiple soft, pointed, watery excrescences about the labia and perineum.

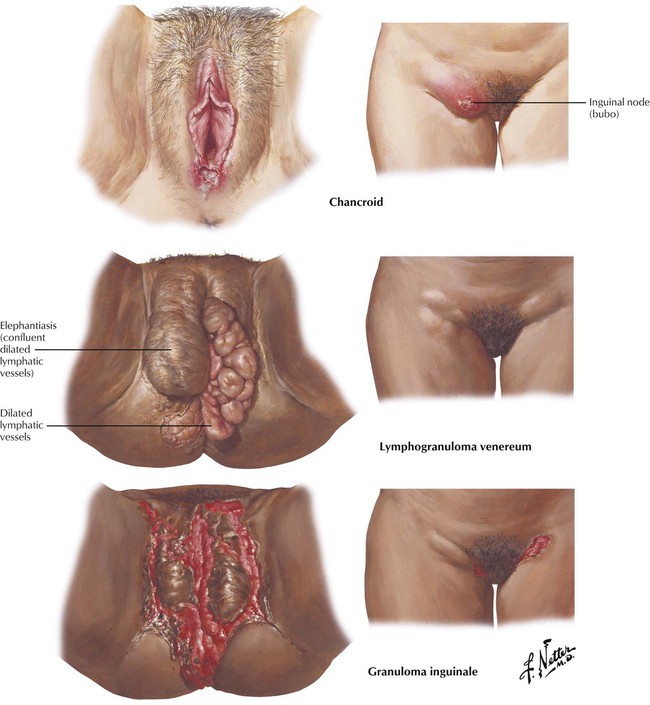

Chancroid, a venereal infection caused by the Ducrey bacillus (Haemophilus ducreyi), is a painful ulcerated, inflamed lesion that develops 3 to 10 days after infection. It is associated with suppurative inguinal nodes or buboes. Lymphogranuloma venereum, which is caused by strains of Chlamydia trachomatis, begins as a papule, a pustule, or an erosion on the vulva or within the vagina. Lymphatic spread leads to the development of inguinal adenitis, a painful matted mass of glands with periadenitis and occasional suppuration and draining sinuses. Complications include rectal stricture. Granuloma inguinale is a chronic infectious disease that is widespread in the tropics and common in the southern United States. After a variable incubation period, the primary lesion develops as a vivid, circumscribed, granulomatous nodule involving the vulva, the vaginal mucosa, or the cervix. Healing occurs slowly, with the lesion persisting for many months or years.

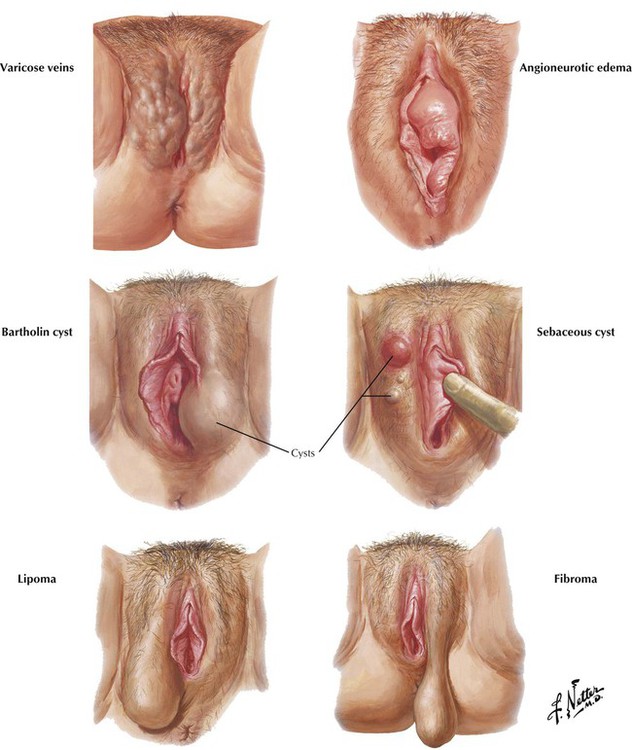

Varicose veins of the vulva are associated with varicose veins of the lower extremities that develop as a result of retarded venous flow caused by increased intrapelvic pressure during pregnancy. Angioneurotic edema is a transient recurrent allergic reaction that manifests as painless swelling of the vulva and other areas of the body. Bartholin cysts result from obstruction of the excretory duct or one of its subdivisions due to specific or nonspecific infections and accidental or operative trauma. Sebaceous cysts result from occlusion of a sebaceous duct, which causes sebum and epithelial debris to be retained in the gland. Benign tumors of the vulva include the fibroma, fibromyoma, lipoma, papilloma, urethral caruncle, hydradenoma, angioma, myxoma, neuroma, and endometrial growths. Fibromas, which arise from vulvar connective tissue, become pedunculated as they increase in size and weight. Lipomas of the vulva are soft proliferations of benign adipose tissue.

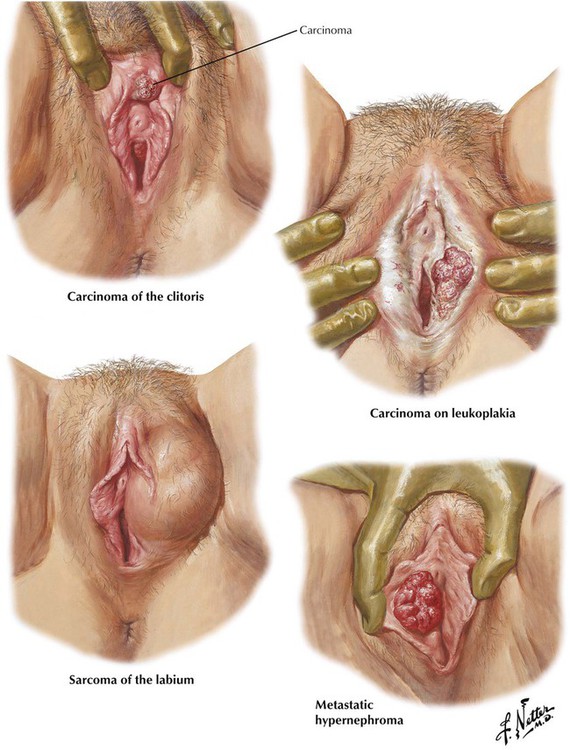

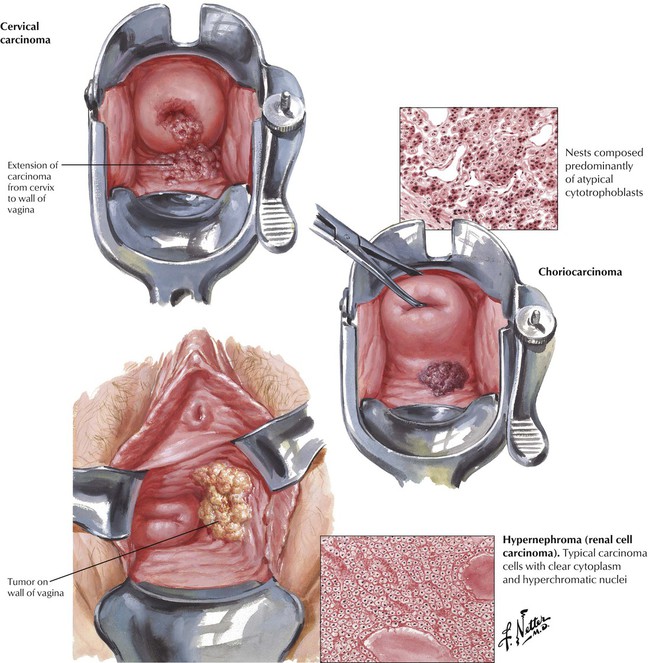

Primary vulvar lesions account for approximately 5% of the malignant tumors of the female genital tract. Primary carcinoma of the vulva or clitoris almost always develops in elderly women. Most are SCCs, and approximately 50% are preceded by leukoplakia. The typical course is the development of a small, firm nodule that progressively enlarges and ulcerates. Lymphatic extension to the regional inguinal nodes occurs early, but distant metastases are rare. Basal cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of a Bartholin gland or other glandular tissue are less common. Secondary carcinoma of the vulva is uncommon, but it may occur particularly with renal cell carcinoma (hypernephroma), choriocarcinoma of the uterus, and carcinoma of the uterine body or cervix. Sarcoma of the vulva, which includes fibrosarcoma, spindle cell carcinoma, lymphosarcoma, myxosarcoma, and liposarcoma is also uncommon, but it is usually very malignant.

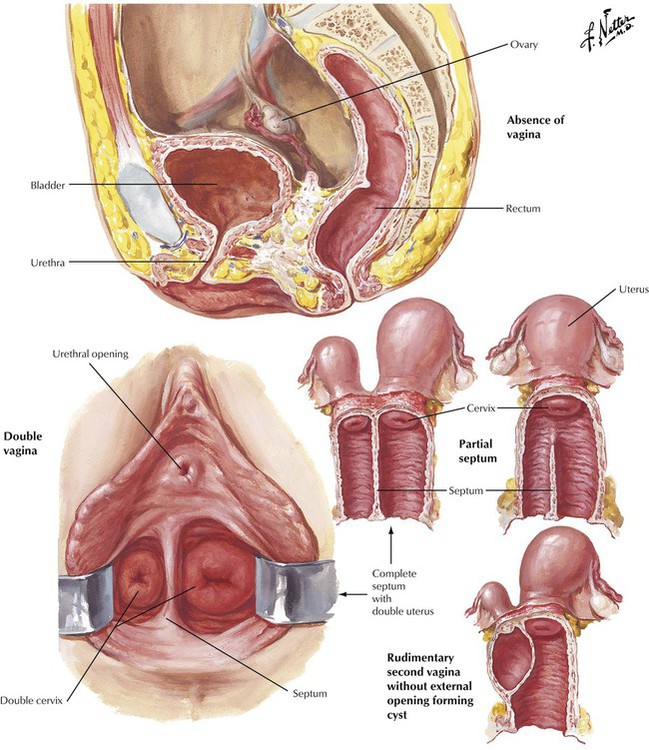

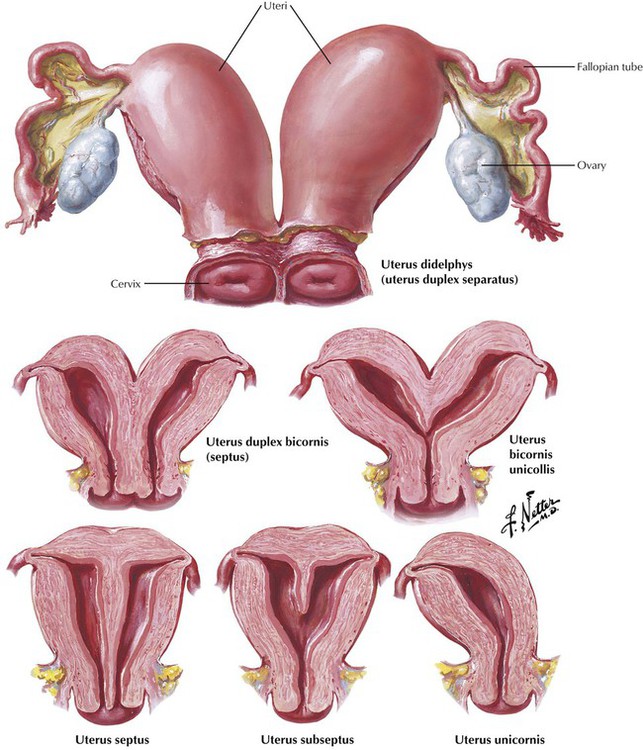

Most congenital anomalies of the uterus and vagina are caused by a failure of the müllerian ducts to fuse completely or to develop after fusion. Absence of the vagina (gynatresia) results from complete lack of union of the müllerian ducts. Each ovary, because it is derived from a different embryonic structure, is normal; the fallopian tubes may be rudimentary. A less extreme failure in müllerian development leads to a double vagina. The partial septate vagina is a milder degree of congenital malformation caused by a failure of the core of solid müllerian epithelium to slough completely at its lowermost portion. Another variation is a rudimentary second vagina. Failure of proper interaction and development of the lower müllerian ducts and the urogenital sinus can lead to an imperforate hymen (external gynatresia).

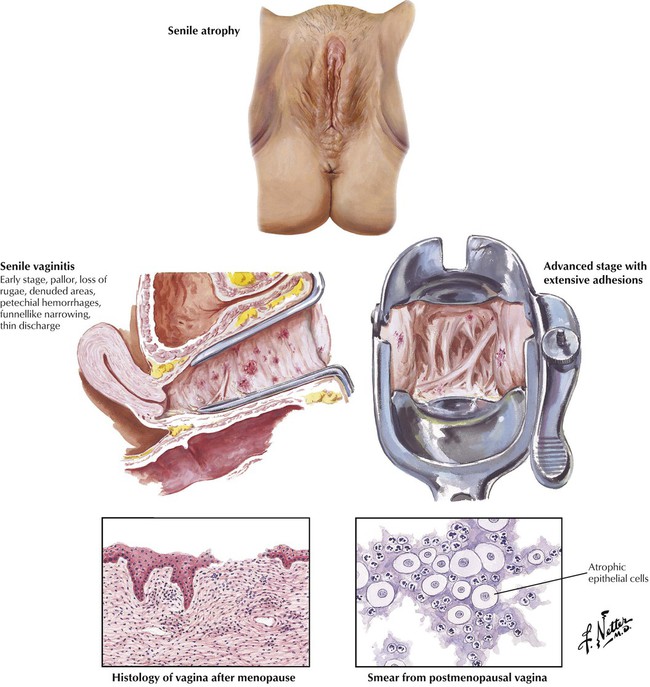

The decline in estrogen levels after the onset of menopause leads to vulvar and vaginal atrophy. The vagina is narrowed, especially near the apex, making visualization of the cervix difficult. The thin mucosa exhibits pallor and petechial hemorrhages, and some ulcerations may be present. Trichomonas or mixed bacterial infections may be present. As the condition advances, attempts at regeneration and repair lead to the formation of adhesions. Histologically, the epithelium is thin and focally interrupted, and the stroma is edematous and contains focal infiltrates of lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cytology of a cervical smear shows atrophic epithelial cells and neutrophils. Senile vaginitis is a common cause of postmenopausal bleeding.

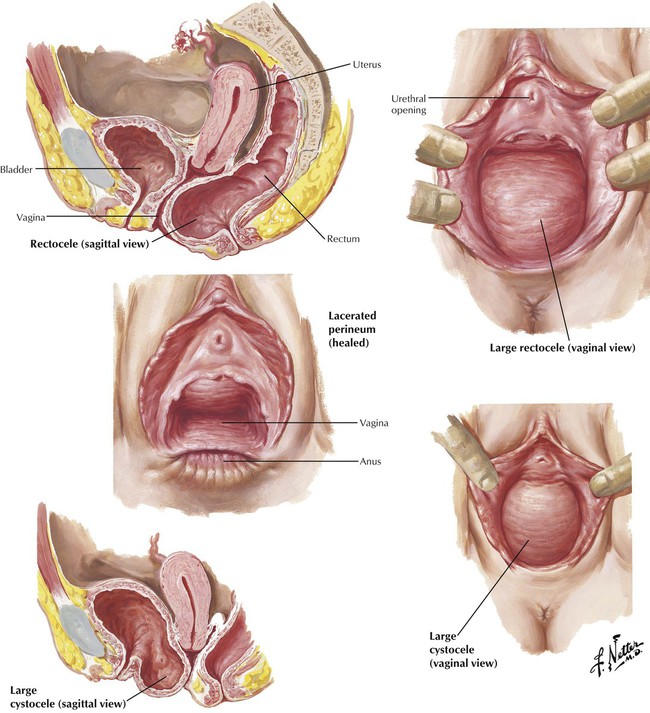

A cystocele, a hernialike structure, occurs when the spreading and tearing of the principal muscular supports of the vagina and rupture of pelvic fascia during childbirth cause the bladder to push forward and downward through the anterior vaginal wall. Fistulae may develop between the vagina and urinary bladder and rectum, diverting the urinary or fecal streams and causing incontinence. The extent of the defect depends on the number and difficulty of previous deliveries and the quality of prepartum and postpartum care. A severe cystocele may produce urinary retention leading to recurrent attacks of cystitis with dysuria, frequency, nocturia, and stress incontinence and may necessitate surgical repair. The consequences of unrepaired posterior obstetric lacerations of the vagina depend on the direction and extent of the tear. Rectocele and varying degrees of prolapse of the pelvic floor may occur in subsequent months. Rectoceles are graded according to size; third degree is a hernia to or beyond the introitus.

Nonspecific or simple vaginitis occurs when the normal vaginal flora of microorganisms proliferate, stimulated by conditions such as age, debility, systemic disease, ovulation, menstruation, or pregnancy. Characteristic features of the infection caused by the protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis are a vaginal and cervical epithelium with small petechial hemorrhages producing a “strawberry” appearance and a thin, greenish-yellow discharge containing many small bubbles, producing a foamy appearance. Vaginal infection due to the fungus C albicans (moniliasis) causes an aphthous ulcerative infection with patchy, white exudate that leaves a raw, bleeding surface when it is removed. Predisposing factors are diabetes and previous use of antibiotics. Vaginitis can be produced by chemical irritation from substances in douches and from foreign bodies in the vagina.

In the vagina, the syphilis chancre, with its raised indurated border surrounded by a shallow ulceration, is most likely to be near the vestibule, and inguinal lymphadenopathy may be present. In the primary stage, serologic test results are often negative, and dark field examination results of a smear from the lesion are positive for treponemes. In late syphilis, white mucosal patches that coalesce and ulcerate focally may be present in the vagina and the external genitalia. Gonorrhea involves the cervix, but spares the vagina during reproductive life because the vaginal epithelium is resistant to infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gonorrheal vaginitis is a recognized but rare clinical entity in the postmenopausal period and in childhood. Tuberculosis, which rarely affects the vagina, is secondary to tuberculosis of the fallopian tubes, the uterus, and the cervix. Typical ulcerated lesions usually involve the posterior vagina.

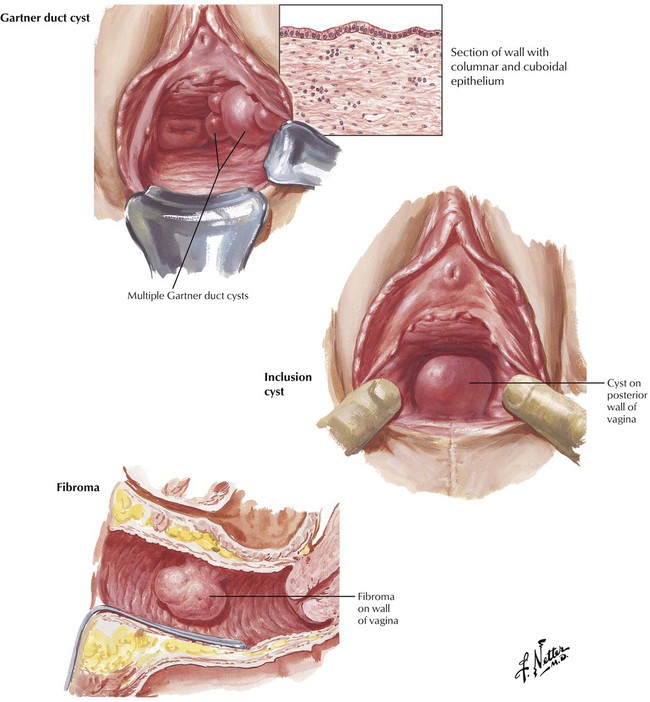

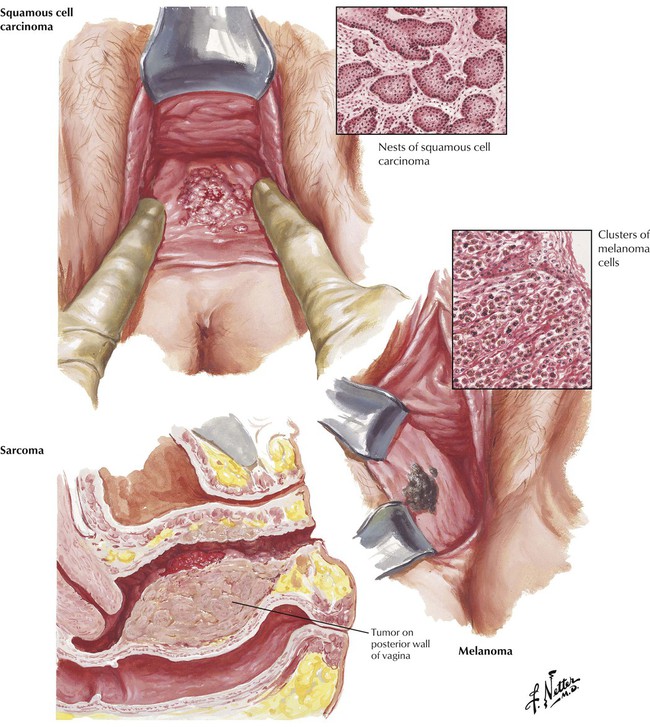

Most vaginal tumors are benign cysts. Gartner duct cysts are formed from embryonic epithelial remnants of Wolffian ducts, are located on the anterolateral vaginal walls, may be simple or multiple, and occasionally attain large enough size to produce pain and other symptoms. Congenital cysts of müllerian origin (inclusion cysts) may occur in the fornices or lower in the vagina. Malignant tumors include primary carcinoma of the vagina, which is usually an SCC that begins as a small growth of the posterior vaginal wall and progresses to infiltrate the vagina and eventually the adjacent pelvic viscera and regional lymphatics, and the rare vaginal sarcomas, fibrosarcoma, and variants in adults and sarcoma botryoides in children. Melanoma of the vagina is unusual, but can occur as an apparently primary lesion or, more commonly, as part of metastatic disease.

Approximately 60% of vaginal malignant tumors are secondary to other tumors, most often carcinomas of the cervix or endometrium. After hysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma, the vaginal vault is a common site of recurrence. Vulvar carcinomas may involve some or most of the vagina. The vagina is the most frequent site of metastases from uterine choriocarcinoma and may be the earliest clinical manifestation. A history of recent pregnancy may be elicited. The dark-purple hemorrhagic gross appearance and the histologic picture are characteristic. The lesion is made up of clusters of syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts, with the trophoblastic cells exhibiting large, hyperchromatic nuclei and frequent mitoses. Renal cell carcinoma, or hypernephroma, may metastasize to the vagina, forming a nodular, yellow tumor mass, usually composed of clear cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Metastases or extensions may involve the vagina before or after treatment of carcinomas of the ovary, the bladder, or the rectum.

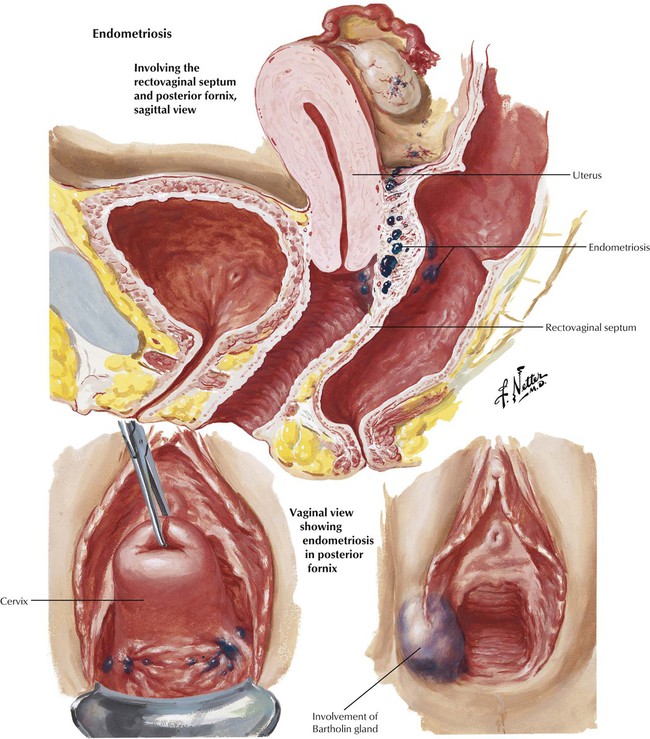

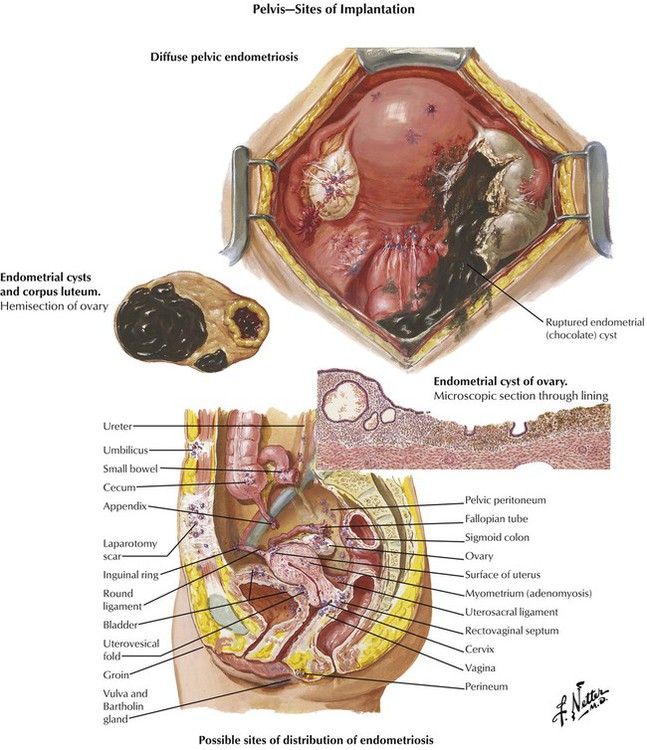

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of hormonally responsive endometrial glands or stroma in abnormal locations outside the uterus. Endometrial tissue can result from retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes, metaplasia of coelomic epithelial implants, or vascular or lymphatic dissemination of tissue from the endometrium. Vaginal endometriosis is associated with similar lesions in the ovary and rectovaginal septum. The sagittal section shows a distribution of endometriosis on the surface of the ovary and other implants on the adjacent peritoneum of the posterior cul-de-sac and the lateral pelvic wall. Blue-domed endometrial cysts extend down the rectovaginal septum, which causes the anterior rectal wall to adhere to the posterior surface of the uterus. Occasionally, there may be involvement of the vulva or perineum and, rarely, a Bartholin gland.

A variety of congenital anomalies are related to the embryologic derivation of the female genital tract from the müllerian ducts. Complete failure of fusion of the müllerian ducts results in the formation of 2 separate genital tracts with completely independent uteri and a fallopian tube attached to the lateral angle of each uterus (uterus didelphys). Each uterus can function separately and sustain a normal pregnancy. More frequently, partial fusion of the müllerian ducts takes place, as is the case in the uterus duplex bicornis. If failure of fusion occurs only at a higher level, the result is 2 uterine bodies with a single cervix, the uterus bicornis unicollis. In some cases, the uterine cavities are completely or partially separated by a thin septum, giving rise to uterus septus or uterus subseptus, respectively. Uterus unicornis is a half uterus arising from only 1 formed müllerian duct. Uterine aplasia with blind fallopian tubes also is known to occur.

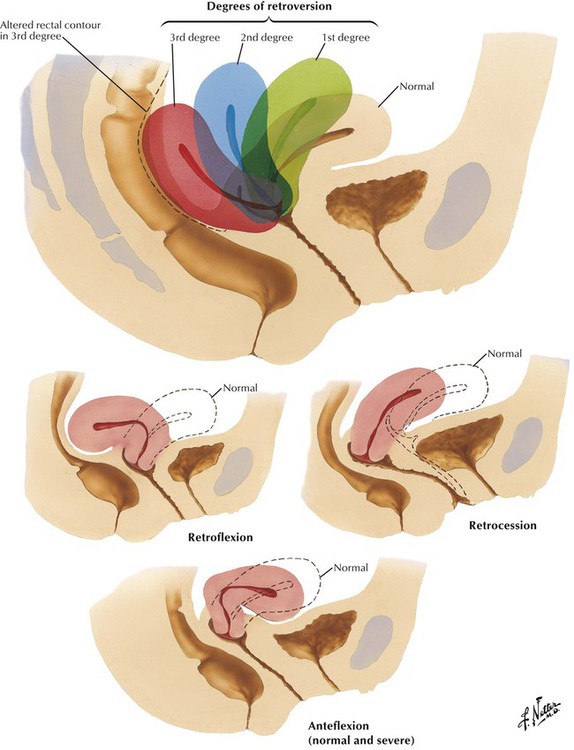

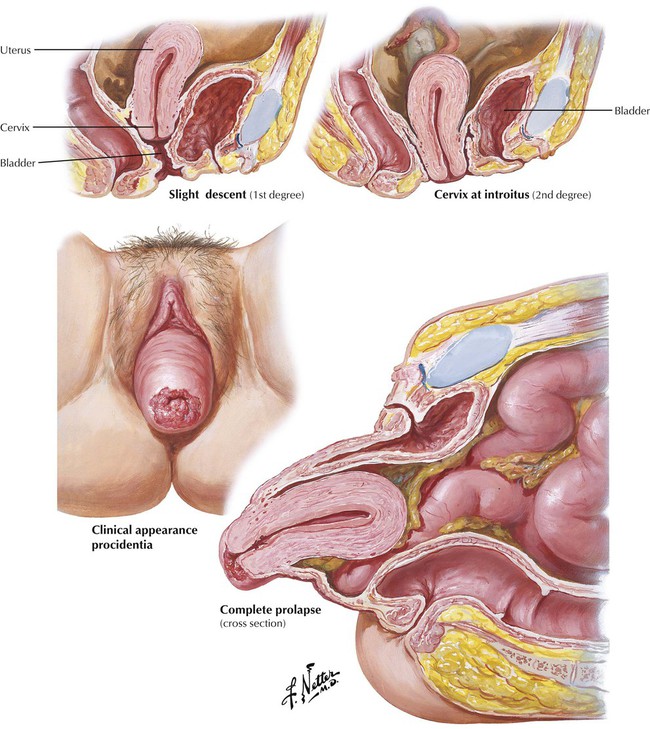

Displacement of the uterus occurs when it becomes fixed or rests chronically in an abnormal position. The anatomical configurations are retroversion, retroflexion, retrocession, and anteflexion. Prolapse refers to descent of the uterus down the vaginal canal so that it lies below its normal position. Some degree of retroversion is present. Usually, this occurs after parturition when the stretched uterine ligamentous supports cannot counteract the usual intraabdominal pressure and the involuting uterus lacks normal myometrial tone. In first-degree prolapse, the cervix does not protrude at the introitus. In second-degree prolapse (procidentia), the cervix protrudes. In complete procidentia, the entire uterus

protrudes. Cystocele and rectocele are frequent complications. Spontaneous rupture of the uterus is a rare complication of parturition or may occur during procedures such as dilatation and curettage, especially when there is preexisting displacement with anatomical malposition of the uterus.

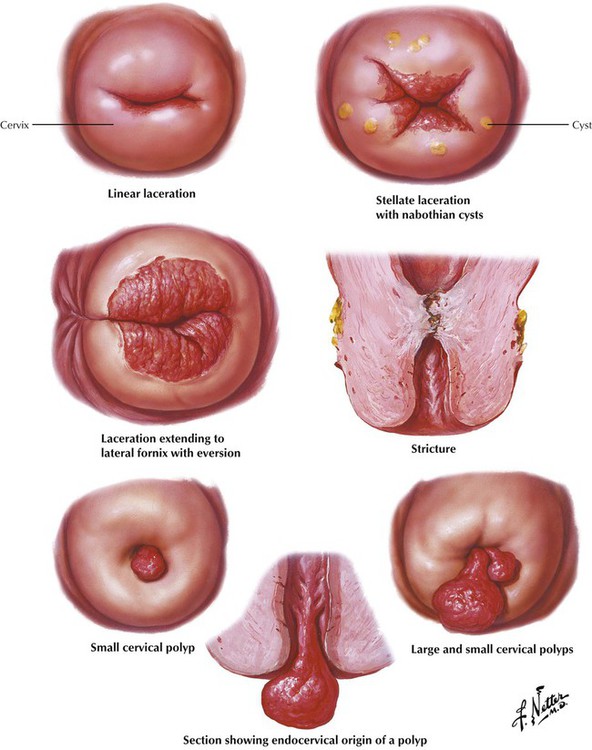

Lacerations of the external cervical os are common after parturition, and, barring infection, most heal spontaneously. More complex lacerations penetrate deeply into the endocervical stroma or extend into the lateral fornix, which permits eversion of the lining of the endocervical canal, predisposing to infection. Stricture of the internal cervical os, which can result in hematometra (retained menstrual flow and endometrial debris), occurs after posttraumatic or postinfectious scarring, after radiation therapy, and in rare cases of partial or complete congenital atresia. The uterine mucosa can form polyps, which differ from endometrial polyps etiologically and clinically. Endocervical polyps, which are usually benign, typically contain all the elements of the endocervical mucosa (columnar epithelium, fibrous stroma, and glands). As the polyps grow to produce protruding soft, red, granular lesions, they can produce mild vaginal bleeding. The etiology of cervical polyps is unknown.

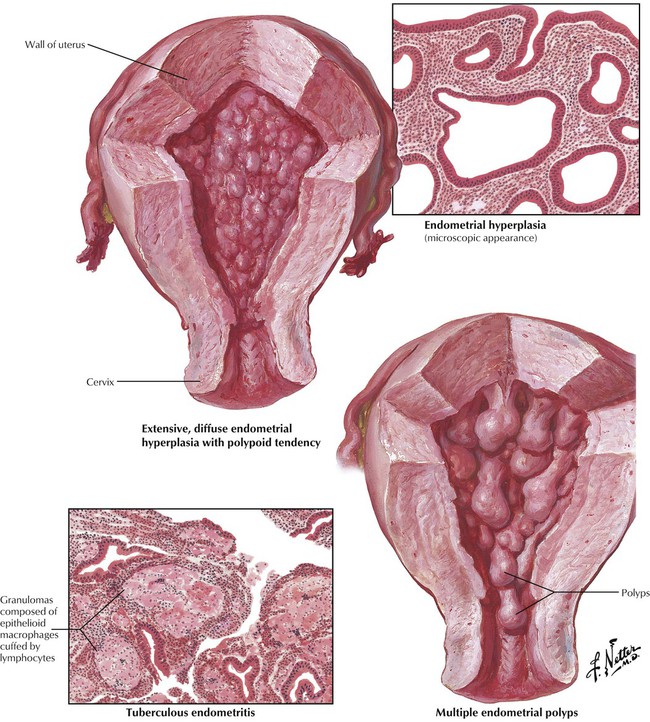

Endometrial hyperplasia occurs under conditions that produce a constant stimulus of estrogen, which prevents the progestational or secretory phase of the menstrual cycle to take place. The gross appearance of endometrial hyperplasia is a thickened and edematous mucosa. Estrogenic stimulation produces an overgrowth of glands, stroma, and microvessels. In long-standing cases, the glands show irregular cystic dilatation with a lining of low cuboidal epithelium, which leads to the “Swiss cheese” pattern. The exuberant growth may be difficult to distinguish from well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Atypical hyperplasia is defined as complex glandular crowding and cytologic atypia. Endometrial hyperplasia may give rise to single or multiple endometrial polyps. The diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia usually is made from pathologic examination of endometrial curettings from a woman with abnormal uterine bleeding. Occasionally, examination reveals an infectious process, including tuberculosis. Tuberculous endometritis is characterized by caseating granulomas in the endometrial stroma.

Exposure of the mucous glands in the endocervical canal, which is often due to erosions from congenital defects or childbirth injuries, is a key factor in initiating cervical infections. The even, concentric appearance of congenital erosions contrasts sharply with the jagged papillary granulomas that usually result from inadequately treated lacerations of childbirth. Spontaneous healing does not occur because the inward growth of squamous epithelium does not cover the infected areas. In areas where healing has occurred, the covering epithelium blocks the exit of previously exposed glands, which produces retention cysts of various sizes (nabothian cysts).

Gonorrheal infection caused by the gram-negative diplococcus Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the most common cause of acute cervicitis. The infection begins in the lower genital tract and does not ascend to the adnexa until the next menstruation. Initially, acute infection involves the deeply branching cervical and endocervical glands, the urethra and the Skene glands, and the Bartholin glands in the vulva. At the time of menses, the gonorrheal infection ascends through the uterus to the fallopian tubes, which become swollen, inflamed, and tortuous. Inflammation of the endosalpinx leads to extrusion of pus from the edematous fimbriae into the posterior cul-de-sac, causing pelvic peritonitis. Lymphatic involvement of the mesosalpinx can predispose to bacteremia and septicemia. A minority of cases of acute cervicitis is caused by pyogenic infections of cervical glands exposed by unhealed lacerations of childbirth. Gram staining of smears may reveal a mixed bacterial population and neutrophils.

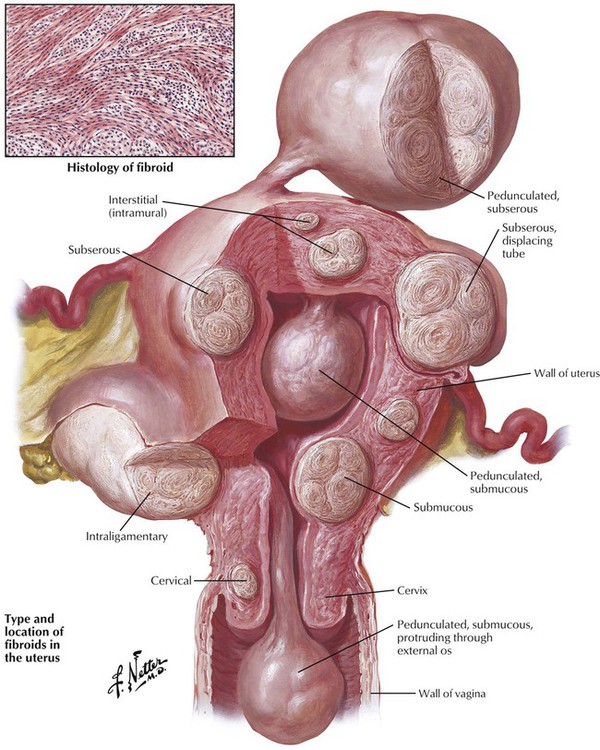

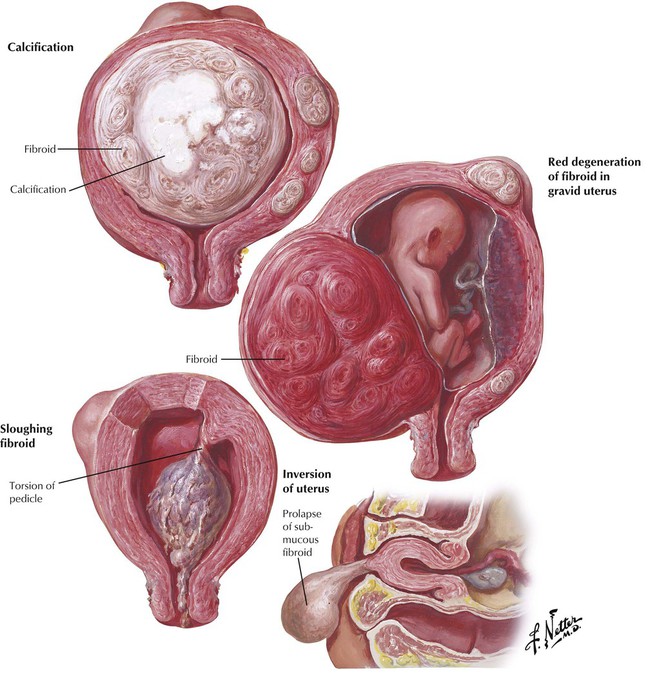

Uterine myomata, the most common tumors in the female pelvis, have an incidence of approximately 4% to 11% in adult women. Commonly called fibroids, these tumors are composed of benign proliferations of uterine smooth muscle cells with a typical whorled pattern on histologic examination and are, therefore, leiomyomata. The tumors, which vary in size, location, and position (intramural, subserous, or submucosal), occur most frequently in the fifth decade of life and are more common in black women. Leiomyomata also are found in the cervix and broad ligament (intraligamentary myoma). The most common symptom, profuse or prolonged uterine bleeding, occurs in approximately 50% of cases. The uterine bleeding and the growth of the leiomyomata may have a common cause in excess estrogen stimulation, so that excision of the leiomyoma may or may not cure the uterine bleeding.

The evaluation of infertility should take uterine leiomyomata into account, particularly if there are submucous myomas. Indications for surgery, either removal of the leiomyoma (leiomyectomy) or hysterectomy, include recurrent uterine bleeding, pelvic pressure, pelvic pain, and rapid growth suggesting sarcomatous transformation. Pedunculated submucous leiomyomas are prone to torsion of the pedicle, cutting off the blood supply and causing sloughing and necrosis. Occasionally, a myoma on a long pedicle can prolapse through the cervix and cause complete inversion of the uterus. Large leiomyomas sometimes exceed their blood supply, leading to cystic degeneration and calcification. Leiomyomas may not affect a successful pregnancy but, if located in the cervix, may obstruct the passage of the fetal head through the birth canal. During pregnancy, the vascular supply to an interstitial leiomyoma may become compromised, leading to necrosis and hemorrhage, so-called red degeneration, which may become a serious complication.

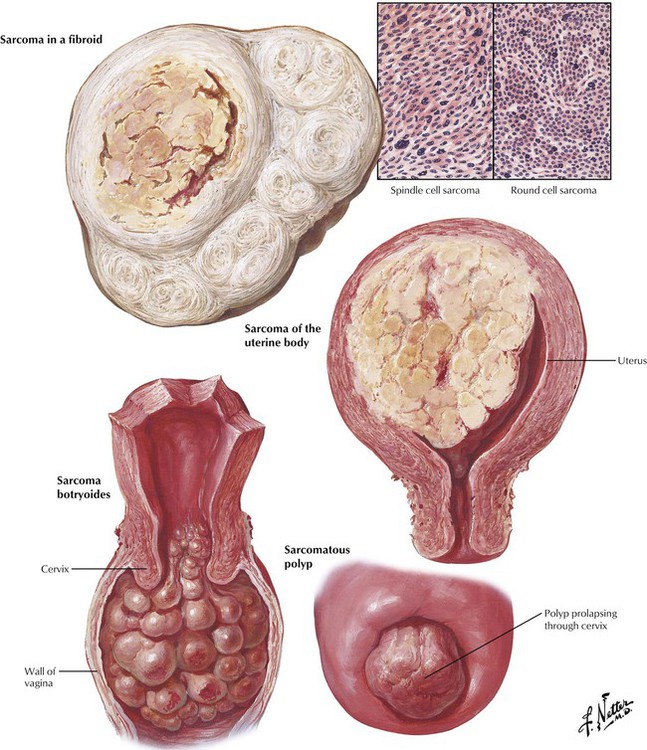

Sarcoma of the uterus accounts for approximately 3% to 4% of malignancies of the female genital tract. Uterine sarcomas, whether primary or secondary to a preexisting fibroid (rate of sarcomatous degeneration is approximately 1%), grow rapidly and have a grave prognosis. Sarcomas arising in a fibroid appear grossly as soft, meaty areas, often with foci of central necrosis or hemorrhage due to an inadequate blood supply. The size and extent of tumor are more important for prognosis than is location or histologic characteristics. Histologically, the sarcoma cells may be spindle-shaped or round and show nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses. Occasionally, uterine polyps show sarcomatous degeneration. Sarcoma botryoides (“grape” sarcoma) is a rare and almost invariably fatal condition that occurs only in young children.

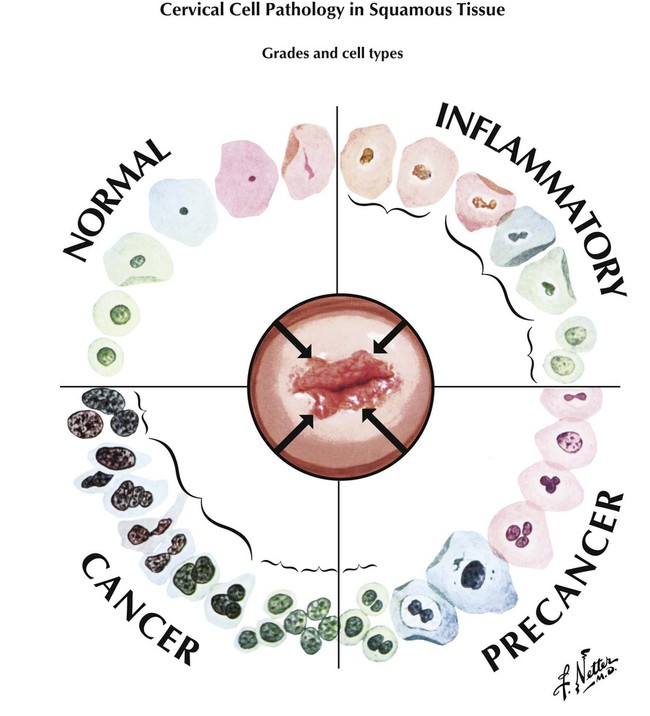

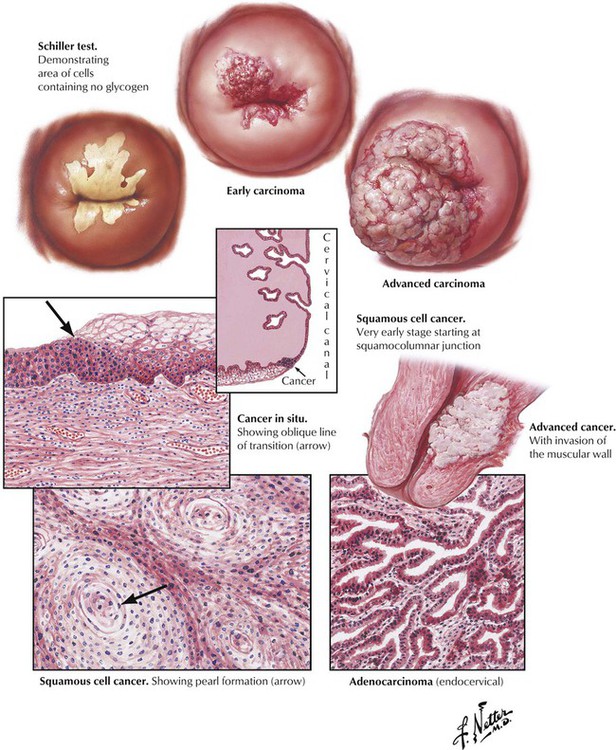

Cervical carcinoma, a slow-growing neoplasm confined for several years to the surface epithelium as a noninvasive growth, is caused by infection by strains of HPV, including HPV-16, 18, 31, and 33. The in situ lesions in the early stage of the disease can be detected by screening with exfoliative cytology of cervical scrapings and vaginal smears (Pap smear) and confirmed by cervical biopsy. In cytologic preparations, cells of the squamous epithelium are classified as basal, parabasal, intermediate, precornified, cornified (keratinizing), and hypercornified. These epithelial cells show a variety of changes during inflammatory processes. The squamous cells show changes generally classified as CIN, ranging from mild dysplasia (CIN grade I) to carcinoma in situ (CIN III), and invasive cancer. These changes are characterized by progressive nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, atypia, loss of maturation, and anaplasia. Viral changes may be especially prominent in CIN I.

Surface carcinoma, CIN grade III, typically originates at the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix and appears histologically as a complete lack of normal basal to surface maturation of the epithelium, coupled with marked nuclear atypia of the cervical epithelial cells. Invasive SCC is characterized by the extension of sheets of atypical squamous cells forming foci of keratinization (epithelial pearls) into the cervical stroma. Adenocarcinoma arises from the endocervical glands and invades the stroma by atypical glandular epithelium. Cervical cancer follows a standard pattern of extension involving the lymphatic channels and direct invasion of adjacent organs. It is characterized histologically according to degree of differentiation (anaplasia) from grade I to grade IV and clinically according to spread of disease from stage 0 to stage IV. Death is more common from uremia secondary to obstructions from local disease than from late metastases to the liver, the lungs, or the bones.

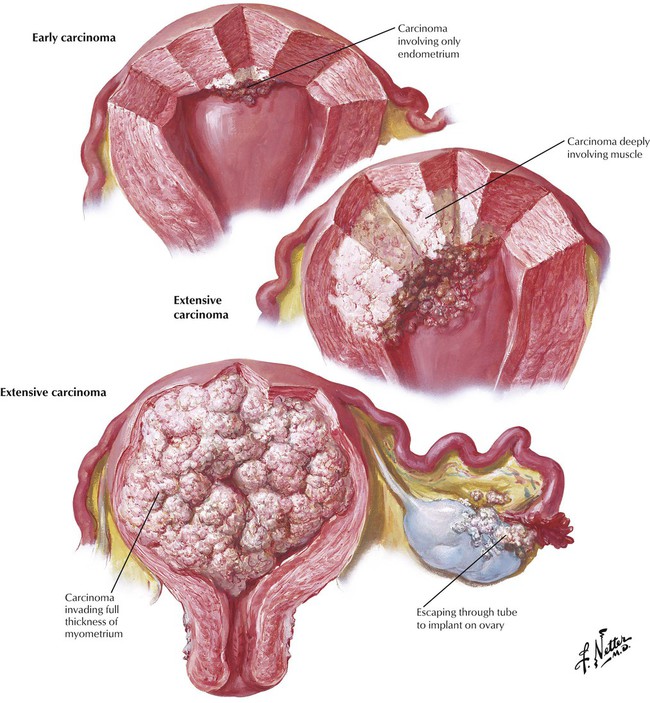

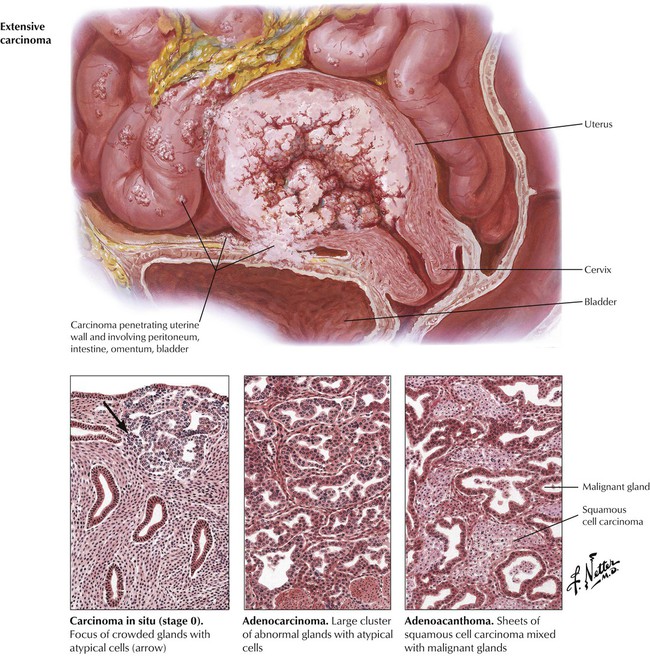

The differential diagnosis of abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, particularly in postmenopausal women, should include adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Detection of endometrial carcinoma in a curettage specimen is diagnostic. Stage 0 designates lesions limited to focal areas of the mucosa. Stage I refers to tumor involving the full thickness of the mucosa, with invasion of the myometrium but limited to the uterus. Stage II indicates tumor that has involved the corpus uteri and the cervix. Stage III and IV designate a cancer that has extended beyond the uterus, including direct extension through the uterine wall or transmigration of cancer cells through the fallopian tubes with implantation on the ovaries. Fractional curettage defines the site of origin of the carcinoma: (1) those that involve only the corpus, (2) those arising only from the endocervix, and (3) those involving both the corpus and endocervix. The importance of the site of origin for staging and therapy reflects different routes of lymphatic spread and invasion.

The histopathologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma can be difficult, particularly differentiation from an atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the endometrium. Foci of adenocarcinoma are characterized by crowded, back-to-back glands lined by thickened layers of epithelial cells exhibiting nuclear hyperchromasia and atypia. Most lesions are pure adenocarcinomas, but some lesions, termed adenoacanthomas, have islands or sheets of squamous carcinoma intermingled with the malignant glands. Location and stage of disease are of paramount importance prognostically, but the more anaplastic tumors may be expected to grow more rapidly and to metastasize earlier than the more mature adenocarcinomas. Successful therapy depends on surgical removal of the disease while it is confined to the uterus. Radiation treatment is used as adjunct therapy. Death from distant metastases to vital organs occurs more often in endometrial carcinoma than in cervical neoplasms.

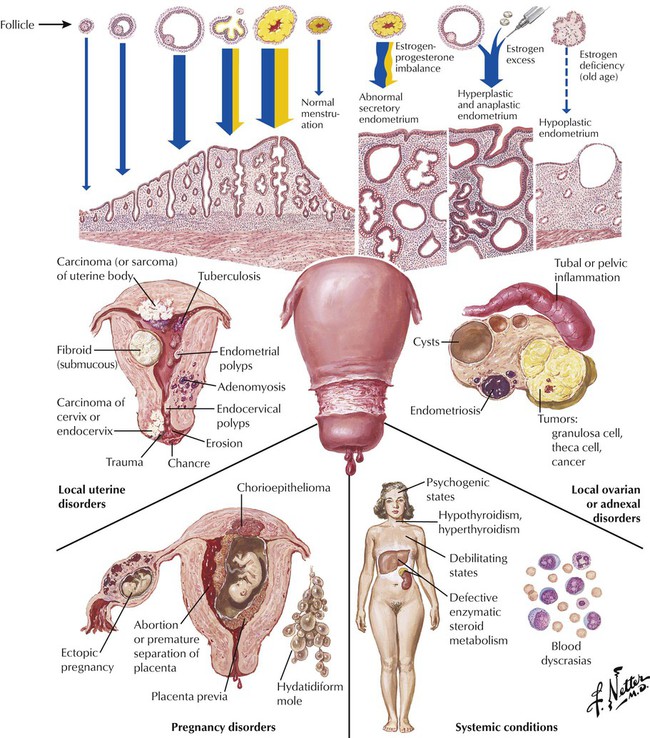

Normal desquamation of the uterine mucosa with menstrual bleeding is controlled through a delicate balance of pituitary and ovarian hormones and the response of the target tissue, the endometrium. Steroid withdrawal bleeding is often associated with persistent estrogen phases and anovulatory cycles. It may follow a state of estrogen-progesterone imbalance, which produces an abnormal secretory endometrium. Excess estrogen produces hyperplastic and anaplastic endometrium, while an estrogen deficiency produces a hypoplastic endometrium. The major categories of pathologic states that can cause or be accompanied by menorrhagia (heavy or prolonged menstrual flow) or metrorrhagia (spotting or bleeding between menstrual flows) are illustrated.

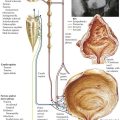

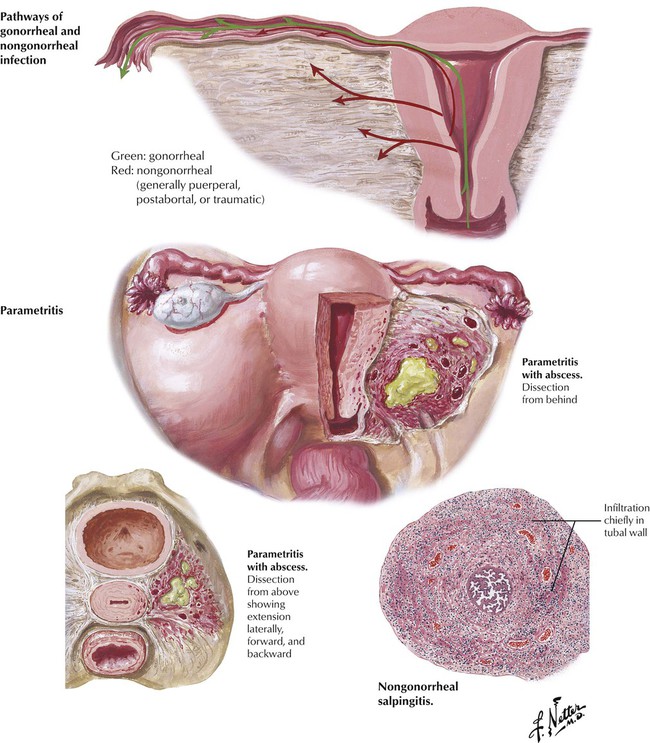

Because the fallopian tubes traverse between the uterus and the ovaries, infection can spread from either the uterus or the ovaries to involve the fallopian tubes producing an acute salpingitis. The opening of the tubes into the peritoneal cavity predisposes the tubes to peritoneal infections, especially appendicitis. Infection by the hematogenous route also may occur as in tuberculosis. Gonococci and most other bacteria reach the tubes by way of the mucous membranes of the vagina and the uterus. Gonococci produce a relatively superficial infection of the mucosa, whereas streptococci and staphylococci typically spread from the mucosa into the uterine wall and invade the adjacent lymphatics, blood vessels, and adjacent pelvic connective tissue, where the most prominent changes with these infections occur. These changes constitute a purulent parametritis, lymphangitis, and thrombophlebitis. Occasionally, a parametrial abscess forms.

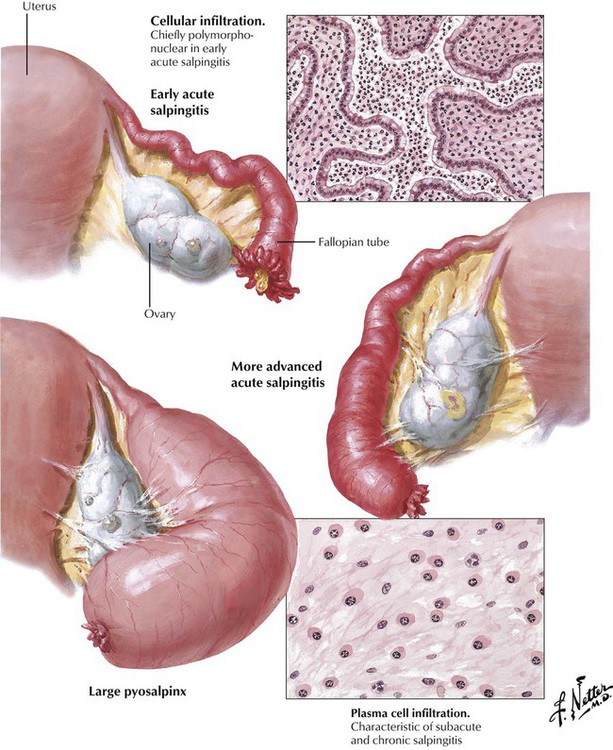

Acute salpingitis is characterized by an edematous, hyperemic, and tortuous fallopian tube with thickened mucosal folds, pus-filled lumen, and a fibrinous or fibrinopurulent exudate on the serosa (perisalpingitis). In gonorrheal salpingitis, the infiltrate is located chiefly in the mucosa. In nongonorrheal salpingitis, the entire wall is inflamed. The loss of epithelium and inflammatory exudate often leads to adhesions of the edematous folds of mucosa. The acute stage is followed by a subacute and eventually by a chronic inflammatory stage. Complications include unilateral or bilateral partial or complete closure of the ampullary ostium, the uterine end, or both the uterine and ampullary sections of the tubes. The closure leads to progressive distention of the tube, forming a sausage-shaped structure called a pyosalpinx. The thick contents of the tube liquefy gradually to become serous or serosanguinous fluid, thus transforming the pyosalpinx into a hydrosalpinx.

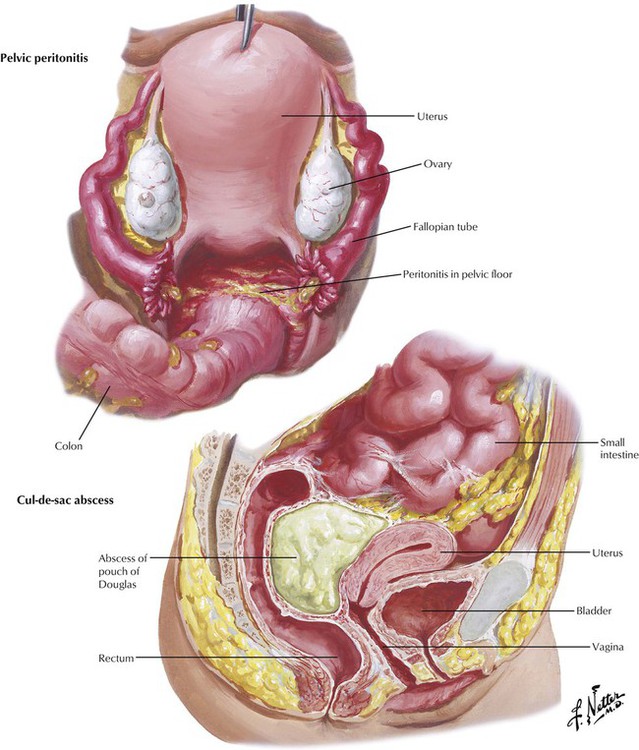

Pelvic peritonitis can result from spillage of the purulent contents of an infected fallopian tube with a patent ampullary ostium or, with obstructed tubes, from spread of tubal lymphangitis and perisalpingitis or rupture of a tube. The severity and extent of the peritonitis depend on the type and virulence of the pathogenic bacteria, the resistance of the patient, and the efficacy of treatment. A pelvoperitoneal abscess, or abscess of pouch of Douglas, results when the pus that has accumulated in the cul-de-sac between the uterus and the rectum becomes sealed off from the rest of the peritoneal cavity by fibrous adhesions between the pelvic organs and the overlying intestinal loops. Pelvic peritonitis usually results in formation of multiple adhesions, which can lead to uterine retroflexion and accompanying pelvic symptomatology. Kinking and fibrosis of the fallopian tubes can lead to infertility.

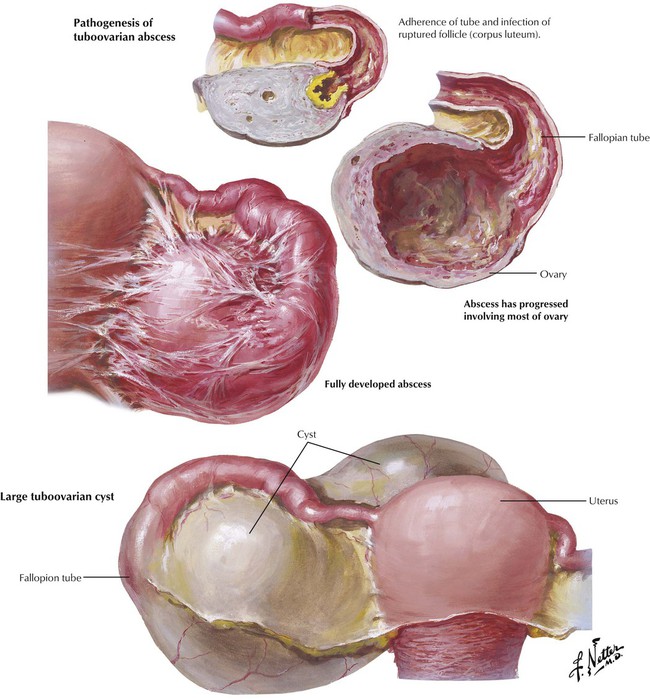

Salpingo-oophoritis is an inflammatory disease involving the ovaries and the fallopian tubes. A tuboovarian abscess forms when a pyosalpinx communicates with a ruptured ovarian follicle or corpus luteum. The ovary may be the site of a bacterial infection or may be involved secondarily from inflammation of the adjacent tube. Generally, follicular or luteal abscesses develop as complications of pelvic peritonitis, whereas ovarian stromal abscesses are usually due to hematogenous dissemination of bacteria. In rare cases, a tuboovarian abscess may gradually become a tuboovarian cyst, which consists of the dilated tube in communication with a large ovarian cyst. The pelvis also may contain mesonephric cysts (congenital cysts) and multiple loculated cysts from Echinococcus infestations (the tapeworm, Echinococcus granulosus).

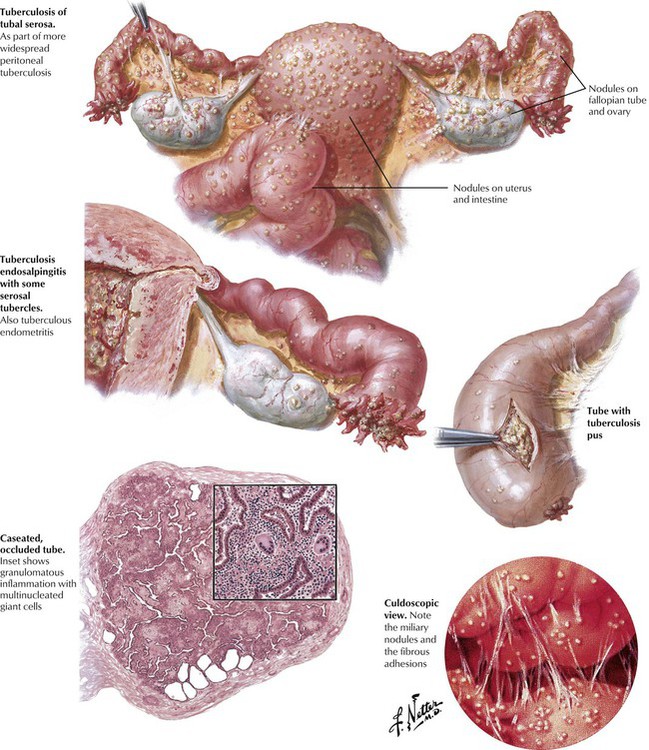

Hematogenous dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, usually from a primary focus in the lungs or hilar lymph nodes, can result in tuberculous infection of the uterus, tubes, and pelvic peritoneum. Usually, both tubes are involved in association with tuberculous peritonitis, and the uterus is involved in approximately half of the cases. Grossly, multiple small nodules consistent with the miliary pattern of tuberculosis are observed. The tubes exhibit caseous necrosis and granulomatous inflammation. The pelvic infectious process can be insidious, and the diagnosis can be difficult to make. The disease process can be exacerbated if diffuse peritonitis develops or if a secondary pyogenic bacterial infection occurs.

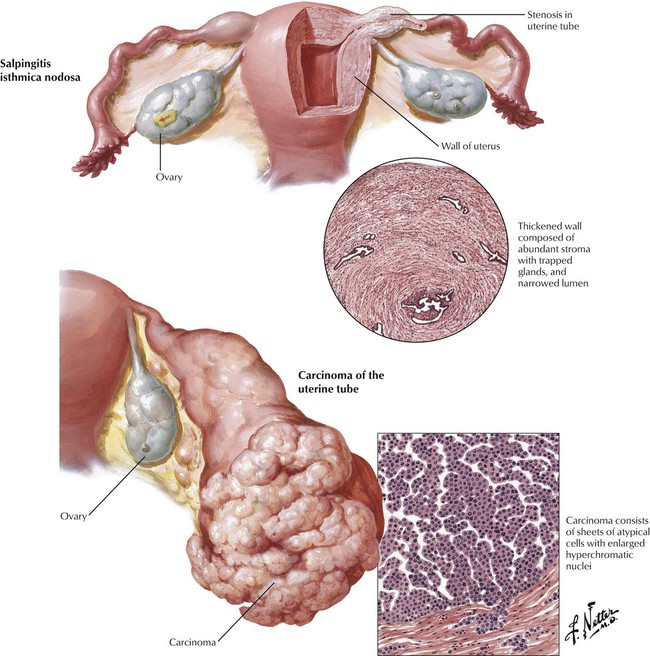

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa, a benign proliferation of stroma and glands similar to uterine adenomyosis, results in an enlargement with stenosis of the inner, isthmic portion of the tubes. Primary neoplasms of the uterine tubes are uncommon and may arise from epithelium (papillomas, adenomas, carcinomas, choriocarcinomas) or the mesenchymal tissue (fibromas, angiomas, leiomyomas, myomas). The carcinomas may be primary in the tubal mucosa or may occur as a metastasis from a primary carcinoma of the ovary, the uterus, or the gastrointestinal tract. The primary carcinomas have the appearance of a distended tube filled with a protuberant growth of neoplastic tissue with multiple papillary projections. The lesions spread by peritoneal implantation as well as by lymphatic and hematogenous metastases. Diagnosis is usually late, and the prognosis is poor.

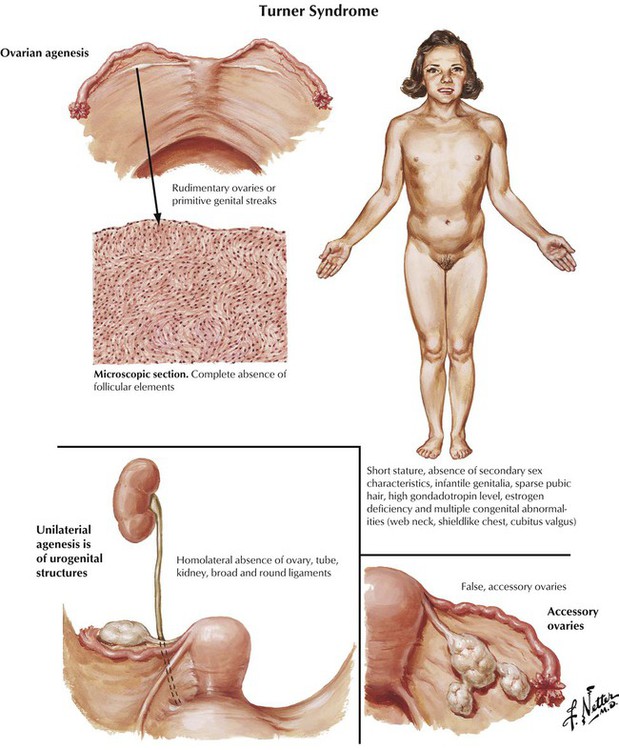

Turner syndrome (ovarian agenesis, ovarian dwarfism) is due to a major defect in ovarian development. This syndrome results from complete or partial monosomy of the X chromosome with a 45, XO karyotype in most subjects and various deletions in 1 of the 2 X chromosomes in the remaining subjects. Turner syndrome is characterized by short stature, infantile genitalia, primary amenorrhea, failure of development of secondary sex features, and multiple congenital abnormalities (web neck, shieldlike chest, cubitus valgus, coarctation of the aorta). The ovaries are rudimentary and consist of stroma without germ cells or follicles. Less common developmental anomalies include absence of one ovary and tube, ectopic ovary, and accessory ovaries.

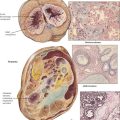

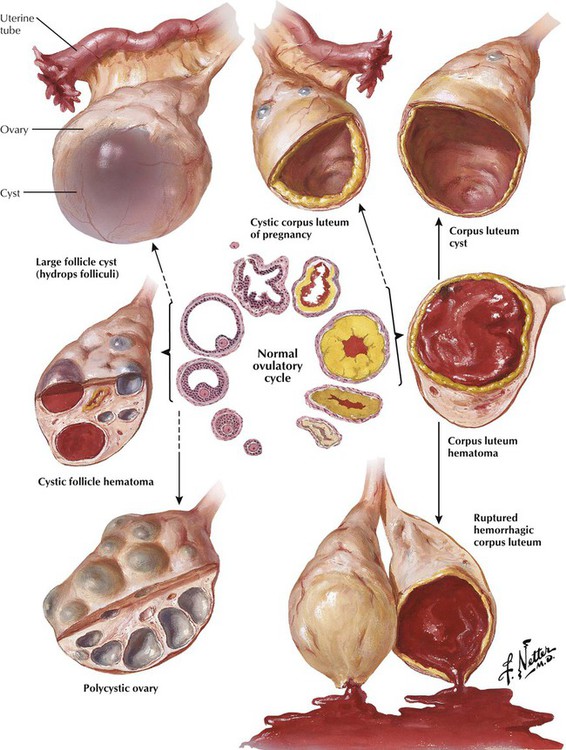

Most small and simple cysts in the ovary represent variations of the normal ovulatory cycle. These cysts are derived from ovarian follicles and corpora lutea and are nonneoplastic but may be mimicked by a small neoplastic ovarian cyst. A corpus luteum of pregnancy can become large and cystic and can be suspected of being an EP. Follicle cysts are distended atretic follicles up to 1 cm in diameter. A polycystic ovary contains multiple cystic follicles. Hydrops folliculi refers to an unusually large follicle cyst that is several centimeters in diameter. A follicle cyst hematoma may result from bleeding into the cyst from the vascularized perifollicular thecal zone. A similar mechanism can produce a corpus luteum hematoma. Resorption of the hematoma produces a corpus luteal cyst, which can convert to a corpus albicans cyst lined by dense collagen. A ruptured Graafian follicle or hemorrhagic corpus luteum gives rise to intraabdominal bleeding.

Pelvic endometriosis results from the nonneoplastic growth of aberrant or ectopic endometrium in response to stimulation by estrogen and progesterone. Pelvic lesions result from periodic proliferation of the aberrant tissue, infiltration of local structures, recurrent bleeding, and fibrosis. Symptoms include sterility, dysmenorrhea, sacral and pelvic pain, and abnormal uterine bleeding. Endometriosis of the ovary occurs as small surface implants, small hemorrhagic cysts within the cortex, or large dark-brown cysts filled with old blood with the appearance of thick chocolate (chocolate cysts). The distribution of the cysts and associated fibrous adhesions render them prone to rupture on manipulation with escape of large quantities of thick, chocolate-colored fluid. The cyst wall may exhibit a lining of typical endometrial stroma and glands, but older lesions may show little evidence of endometrial tissue.

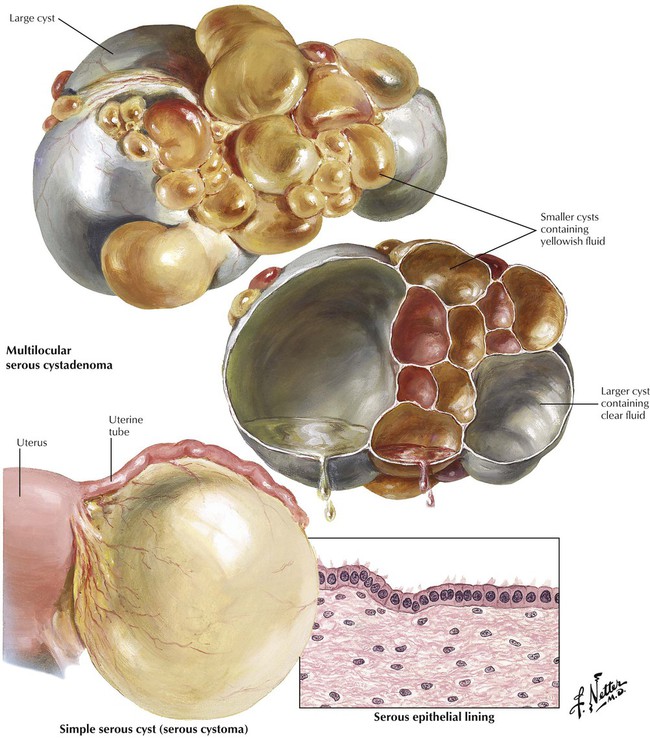

Cystadenomas comprise a group of common benign ovarian neoplasms. Serous cysts include a connective tissue and an epithelial component, with variable predominance of these components. The simple serous cyst (serous cystoma) is a unilocular cyst lined by a simple cuboidal layer of serous epithelium. It is usually unilateral, smooth surfaced, and grayish-white and contains clear, serous, watery fluid. The serous cystadenoma is a unilocular or multilocular serous cyst of the ovary that contains glandlike, epithelial foci in its wall. These lesions are frequently bilateral and are composed of multiple interconnecting cysts of various sizes. Histologically, the cyst walls are lined by a single layer of cuboidal or low columnar ciliated epithelium.

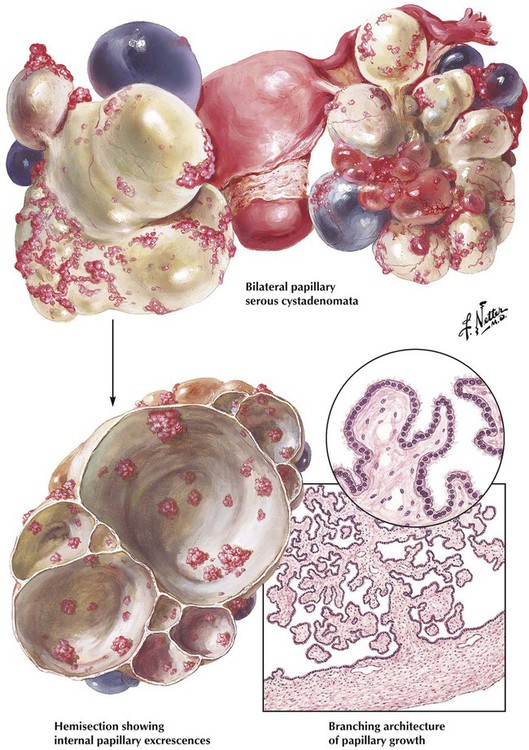

Papillary serous cystadenomas are serous cysts that are typically bilateral and multilocular and exhibit intracystic or extracystic papillary and adenomatous growths, which indicates an increased proliferative tendency. The lesions have the potential to spread slowly in the peritoneal cavity and recur after surgery, thus fitting into the borderline malignant category. The papillary excrescences are the most striking feature of these tumors. Histologically, the cyst wall is composed of fibrous tissue with an inner lining of a single cell layer of serous epithelium. Focal calcifications or psammoma bodies may be present. The cysts and papillae may show focal areas of piling of epithelium or cytologic atypia. They usually occur during the reproductive years (age 20-50 years).

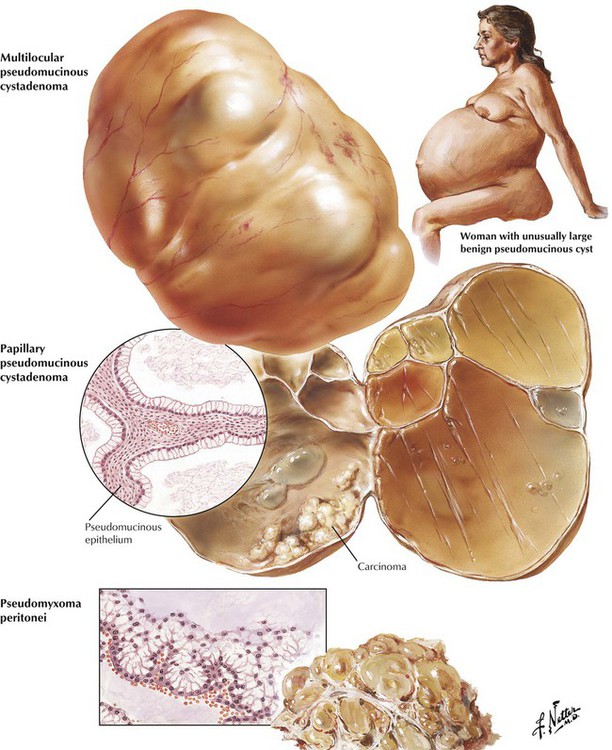

Mucinous cystadenomas are cystic ovarian neoplasms lined with mucous-producing epithelium. Typically, they are unilateral and smooth surfaced, are composed of multiple distended lobules, and occur during the reproductive years. They vary in size, some becoming so large as to distend the abdomen. Microscopically, benign, variants of mucinous cystadenomas show the connective tissue capsule and dividing septa lined by a single layer of tall columnar cells with clear cytoplasm and uniform basal nuclei. More aggressive borderline malignant and malignant lesions exhibit localized, firm infiltrations of the cyst wall with papillary projections on the interior of the cyst. Pseudomyxoma peritonei arises from a mucinous ovarian lesion or, more commonly, from a primary mucinous tumor of the appendix, with subsequent implantation and growth of pseudomucinous epithelium in the peritoneal cavity and progressive enlargement of the abdomen leading to increased abdominal pressure and impairment of bladder and bowel function.

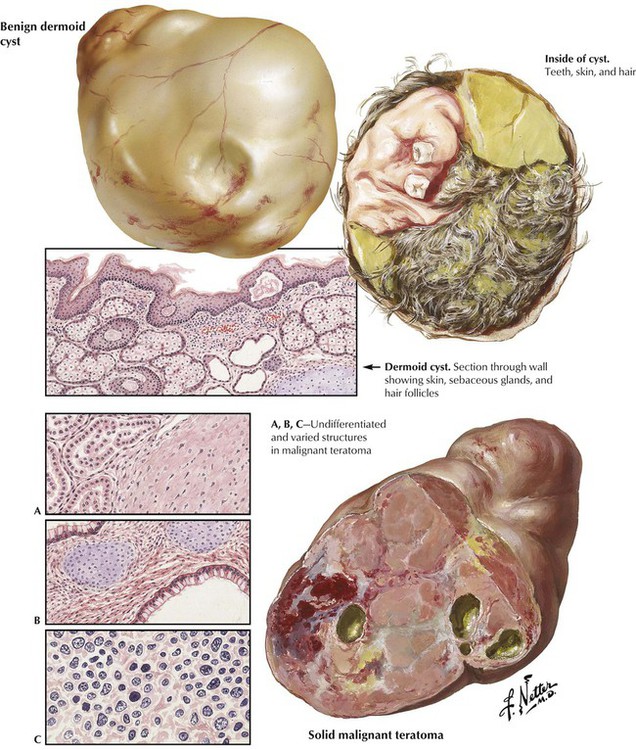

The dermoid cyst (benign teratoma of the ovary) is a common benign cystic neoplasm of germ cell origin with well-differentiated components of the 3 germ layers. The tumors, which are sometimes bilateral and can vary in size, are round or oval, are heavy, have a smooth, gray-white or yellow surface, and contain variable combinations of fatty sebaceous material and strands of hair. Histologically, the wall is lined by squamous epithelium; contents include well-differentiated tissues of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal origin. Malignant transformation, most often as SCC, occurs in approximately 2% of cases. Solid (embryonal) teratomas are rare malignant neoplasms occurring typically in younger women. On cut section, malignant teratomas have a variegated appearance with foci of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cystic degeneration. Microscopically, well-differentiated areas coexist with poorly differentiated elements showing embryonal, undifferentiated, sarcomatous, or carcinomatous features.

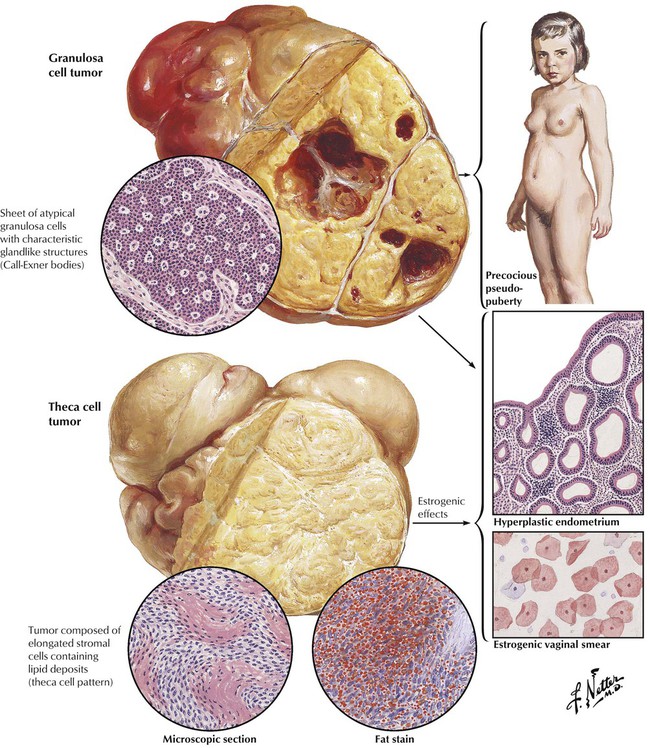

The granulosa cell tumor is a usually benign, but occasionally malignant feminizing neoplasm composed of cells with features and organizational pattern of granulosa cells of the Graafian follicle, including small glandlike structures mimicking immature follicles (Call-Exner bodies). Grossly, the tumors are usually unilateral, soft, and yellow, with focal cystic areas. These hormone-producing tumors occur with approximately equal frequency in young adult and postmenopausal women and may occasionally occur in prepubertal girls, leading to precocious pseudopuberty. Theca cell tumors are benign, unilateral, solid, estrogen-producing neoplasms composed of cells resembling the theca interna. They occur in menopausal and postmenopausal women and rarely in young adults. Histologically, the tumor is composed of interlacing bands of elongated, stromal cells with oval nuclei and vacuolated fat-containing cytoplasm (theca cell features) separated by collagenous bands.

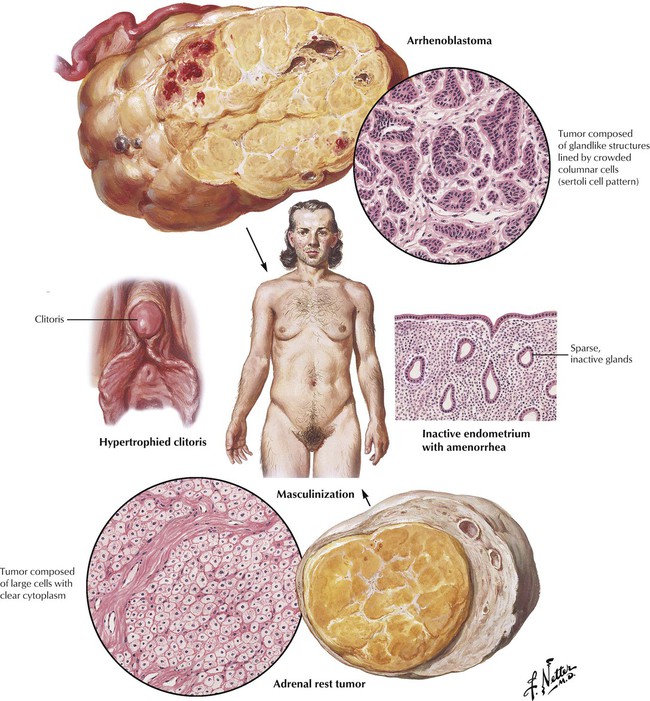

The arrhenoblastoma (sertoli–Leydig cell tumors) is composed of cells that show features of testicular differentiation in the maturing gonad. Most of these tumors occur in young to middle-aged women; 25% are malignant. The tumors are unilateral, solid, smooth, lobulated, encapsulated, gray-yellow neoplasms with numerous foci of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cystic change in cut section. Several patterns occur, including cuboidal or columnar cells forming tubules or glands (sertoli cells), large polygonal interstitial or Leydig cells, and, in some, more primitive areas with poorly organized spindle-shaped or epithelioid cells. Adrenal rest tumors may arise from aberrant adrenal rests in the ovary. These rare tumors are composed of large polygonal cells with central nuclei and clean cytoplasm. Leydig cell tumors are rare neoplasms derived from the hilus cells of the ovary. Virilism associated with these neoplasms includes hypertrophied clitoris, hirsutism, acne, and increased muscularization.

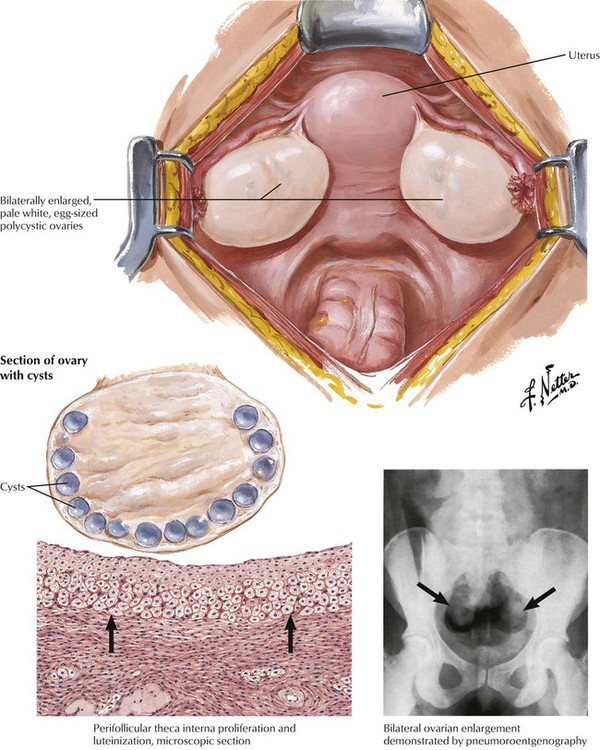

Stein-Leventhal syndrome, characterized by amenorrhea, sterility, hirsutism, and obesity, is often associated with polycystic ovaries. Grossly, the ovaries are enlarged symmetrically and contain many cystic follicles, 2 to 15 mm in diameter, just below the outer, thickened tunica albuginea. Microscopically, there is evidence of hyperthecosis. The theca interna layer surrounding many of the atretic follicles shows prominent proliferation and luteinization, whereas the ovarian parenchyma is hyperplastic with increased cellularity. Stein-Leventhal syndrome is an endocrinologic disturbance involving increased production of luteinizing hormone of the anterior pituitary and ovary (increased luteinizing hormone stimulating the theca cells to produce androgens). Bilateral wedge resection of one half to two thirds of each ovary can lead to renewed menses and fertility in some cases.

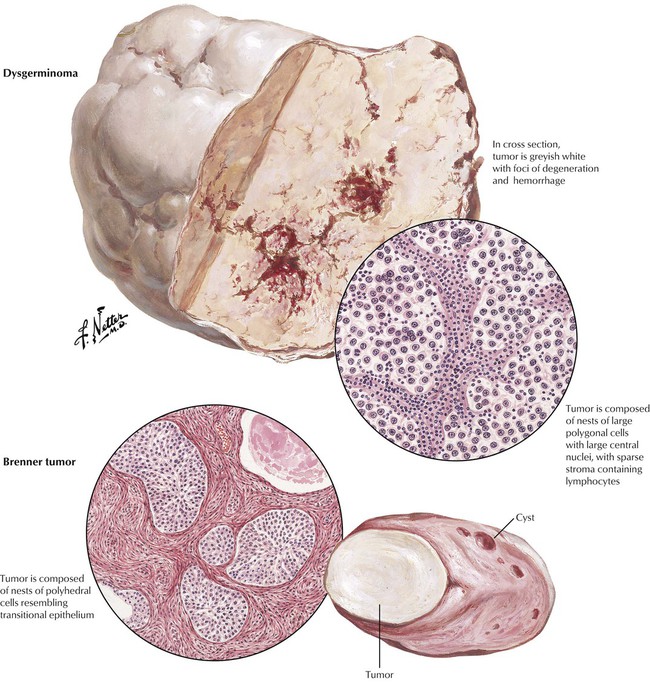

The dysgerminoma is a unilateral, malignant epithelial tumor analogous to the seminoma of the testis. It may be associated with gonadal maldevelopment or pseudohermaphroditism. Most occur in young adults. The dysgerminoma is a solid oval tumor of variable size composed of cords or nests of large, round or polygonal cells with centrally placed, round, uniform nuclei with prominent nucleoli, mitoses, and often an interspersed infiltrate of lymphocytes. Dysgerminomas are malignant but exhibit variability in aggressive growth and spread beyond the capsule. These tumors are radio-sensitive. The Brenner tumor is an uncommon, benign, unilateral, fibroepithelial neoplasm composed of masses of polyhedral cells surrounded by connective tissue that resemble transitional cells of the urinary bladder. Microscopically, the masses of epithelial cells resemble a pavement epithelium. Multiple or solitary small cysts may be present. Most Brenner tumors occur after the age of 40 years or postmenopausally.

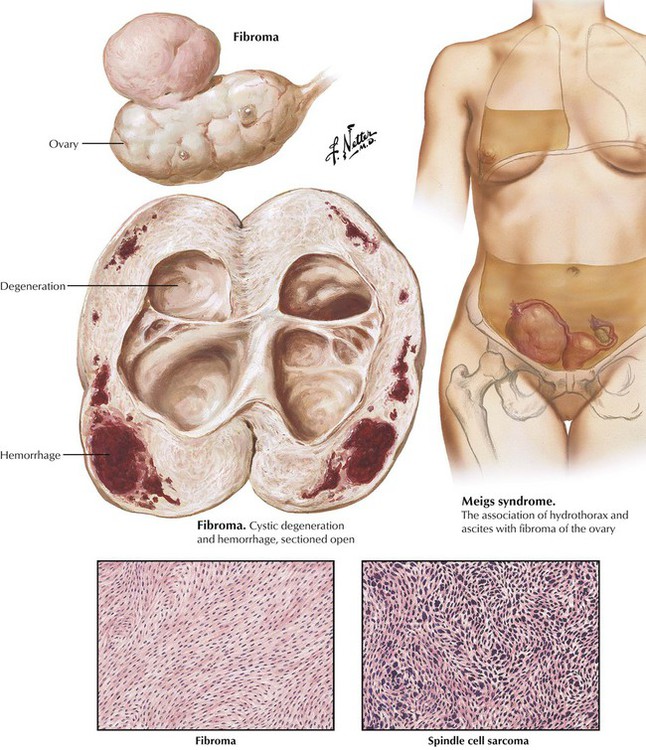

Ovarian fibromas, benign tumors of ovarian stroma, may be small surface pedunculated lesions or large pelvic masses. They are usually unilateral, although a single ovary may show multiple tumors. Most fibromas are found in postmenopausal women, but they can occur at any age. The ovarian fibroma is the most common tumor associated with Meigs syndrome of hydroperitoneum (ascites) and hydrothorax. Fibromas are well-encapsulated, solid, oval, grayish-white tumors composed of dense, white, interweaving bundles of connective tissue and, in the larger neoplasms, focal areas of cystic degeneration and hemorrhage. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of interlacing whorls of spindle-shaped cells with uniform, small nuclei. Removal of the pelvic tumor typically results in resorption of the hydrothorax and hydroperitoneum. Fibrosarcoma of the ovary is a rare neoplasm composed predominantly of spindle cells with irregular hyperchromatic nuclei. Extension may be by direct invasion or via the vasculature.

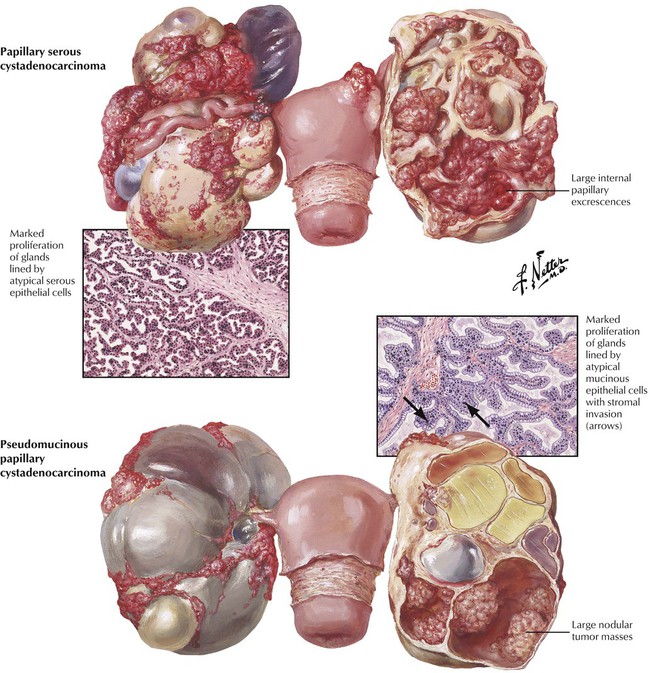

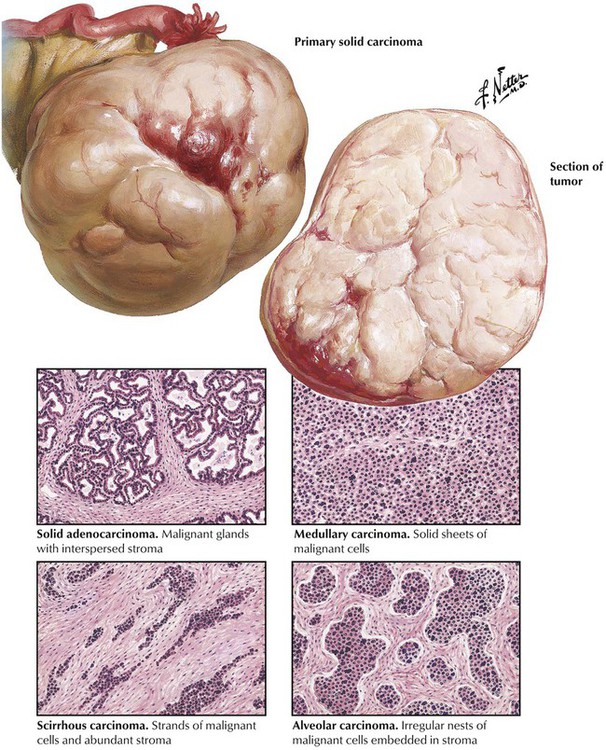

Ovarian carcinomas are either primary or secondary (metastatic) carcinomas. The primary carcinomas may be solid or cystic. Ovarian carcinoma is a major category of malignancy of the female genital tract, ranking next to carcinoma of the cervix and uterine fundus. Most ovarian carcinoma occurs between 40 and 60 years of age. Most ovarian carcinomas are papillary SACs. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma is less common, and mucinous cysts are less likely to be malignant than are papillary lesions. Most ovarian carcinomas are relatively large at the time of diagnosis. Histologic features of malignancy include crowding and piling up of cells with marked nuclear atypia. Bilateral ovarian involvement occurs in one third to one half of cases, depending on the type of malignancy. SACs are more likely to be bilateral than are pseudomucinous cystadenocarcinomas. SCCs may develop in a dermoid cyst.

Primary solid ovarian carcinomas, also designated as the undifferentiated or unclassified group, are classified as solid adenocarcinoma, medullary carcinoma, scirrhous carcinoma, alveolar carcinoma, plexiform carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma with squamous cell metaplasia (adenoacanthoma) on the basis of the pattern and arrangement of the epithelial and connective tissue elements. Carcinoma of the ovary spreads by various routes, including local infiltration, to involve adnexal structures, metastatic spread via retroperitoneal channels to the opposite ovary, lymphatic extension to other pelvic organs and lymph nodes, implantation on the peritoneal lining of the abdominal cavity, and spread to distant organs by either lymphatic or hematogenous routes. Prognosis is strongly influenced by the type of tumor and the extent of involvement at the time of diagnosis.

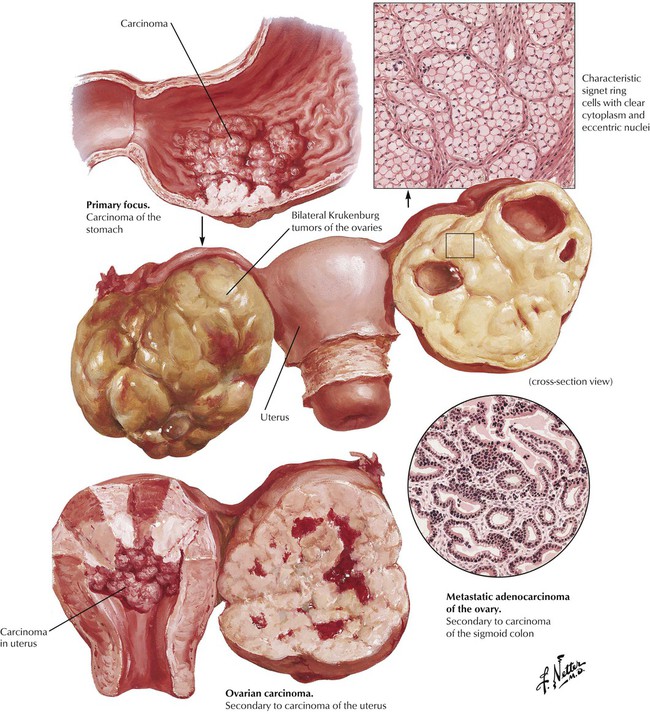

The ovary is a common site of metastatic invasion by carcinoma. The primary sites include the breast, lungs, stomach, colon, pancreas, liver, uterus, tubes, opposite ovary, and urinary bladder. Metastatic ovarian carcinoma occurs most frequently from the fourth to the sixth decades of life. Ascites is a common finding. There is bilateral involvement in up to 75% of cases, and lesions can vary in size from minute to large. The cut surface may be solid and uniform or cystic and mottled, depending on the extent of hemorrhage and necrosis. Other abdominal foci of tumor may be present. The histologic features generally mirror the primary lesion. Krukenberg tumor is a secondary ovarian carcinoma containing characteristic signet ring cells in which the nucleus is flattened to one side by secretion, distending the cell and creating clean cytoplasm. Primary carcinoma of the stomach metastatic to the ovary is a classic cause of Krukenberg tumor. The prognosis in secondary ovarian carcinoma is generally grave.

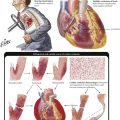

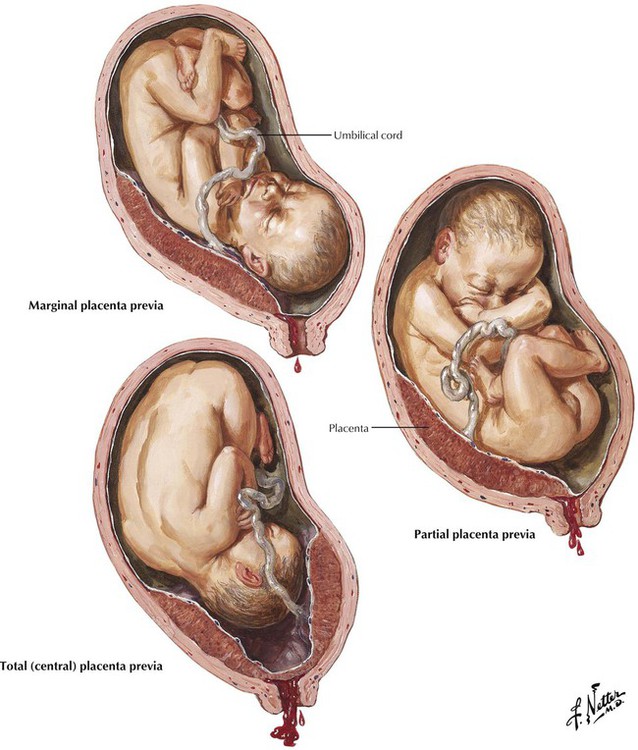

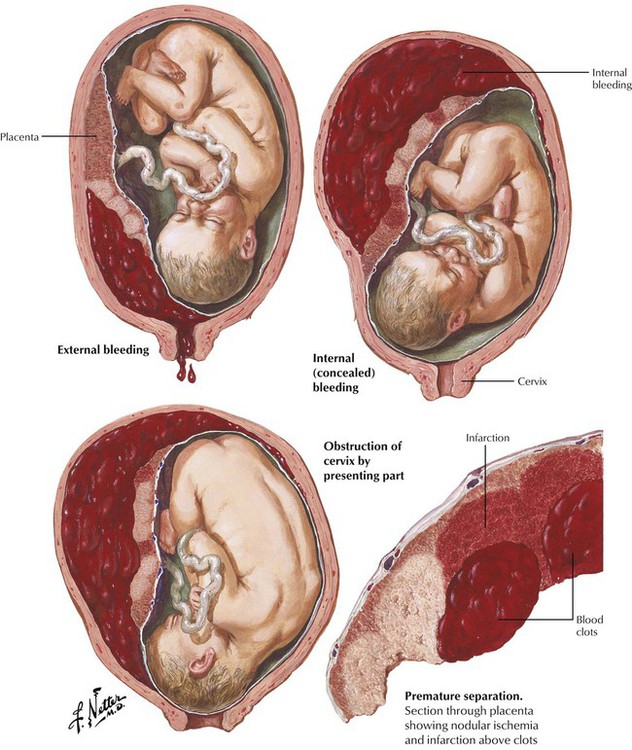

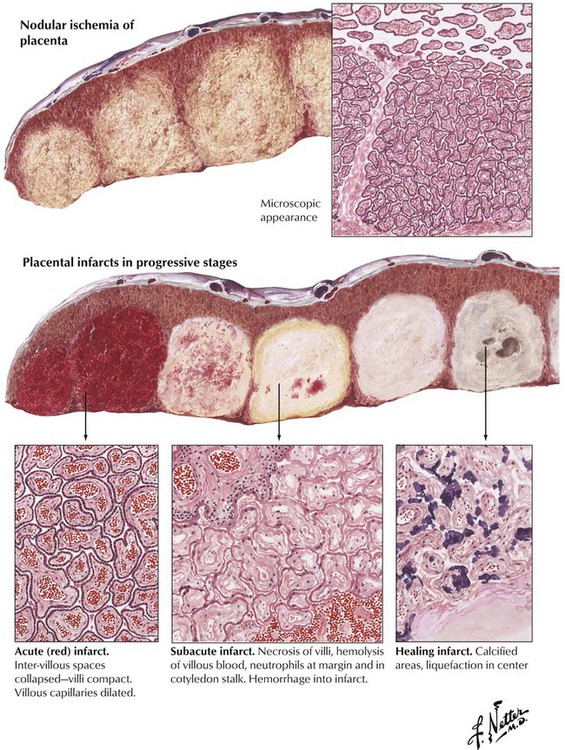

In placenta previa, the placenta is implanted in the lower uterine segment so that it partially or totally obstructs the cervical canal. In abruptio placenta, the normally implanted placenta separates prematurely from its uterine attachment in the late second or third trimester of pregnancy. Placenta previa and abruptio placenta are major causes of uterine bleeding during the last trimester of pregnancy. The bleeding from placental detachment may be internal or external, depending on whether the blood remains concealed between the placenta and the uterine wall because of incomplete detachment of the placenta or obstruction of the cervical canal by the fetus. Most cases of abruptio placenta are associated with toxemia of pregnancy or with chronic hypertension complicating the pregnancy, with associated placental ischemia as often is manifest by a large number of placental infarcts. Abruptio placenta is treated by rapid emptying of the uterus and blood transfusions.

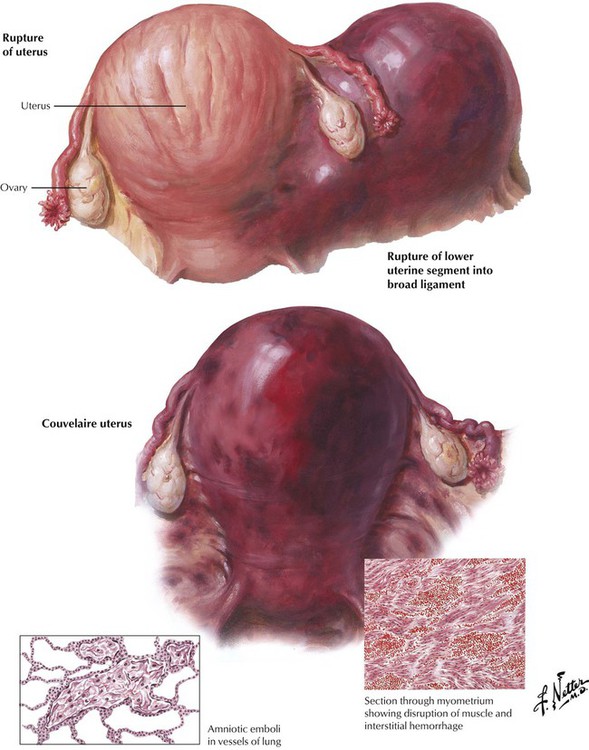

Uteroplacental apoplexy (Couvelaire uterus) is usually associated with severe forms of abruptio placentae. The process is characterized by extensive hemorrhage into the myometrium, the tubes, and the ovaries compounded by defibrination and impaired clotting of the blood. Lifesaving hysterectomy is often necessary to stop the continuous bleeding because the uterus remains atonic after being emptied of the fetus. Rupture of the uterus, which may be traumatic or spontaneous, occurs before (rare) or during labor and often results in death of both the mother and the fetus. Maternal pulmonary embolism by cellular debris containing amniotic fluid is the apparent cause of some cases of sudden obstetric death, with the typical setting being in multiparas with excessive uterine contractions. The clinical course is one of dyspnea, cyanosis, shock, and death within a few hours.

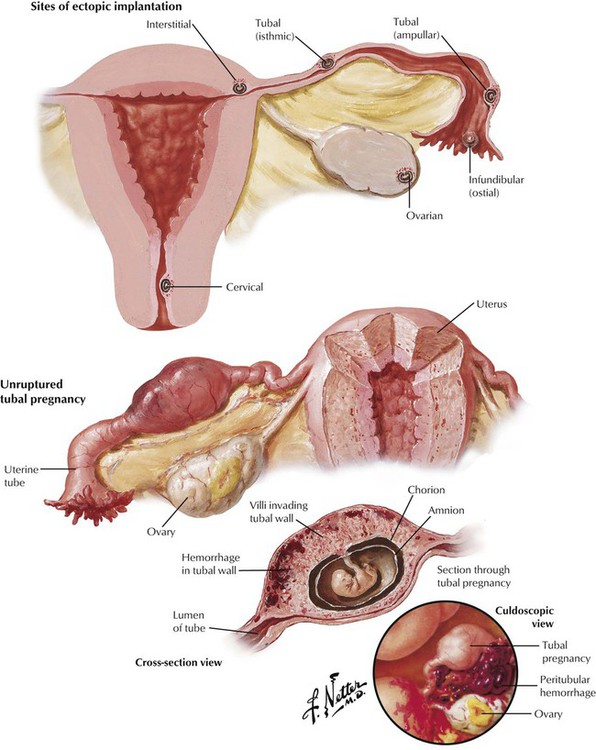

Ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity, which occurs in approximately 1 of 150 to 200 pregnancies. Previous pelvic inflammatory disease with chronic salpingitis is a significant predisposing factor. The site of implantation determines the type: tubal (by far the most common), ovarian, abdominal or peritoneal, and cervical. The subtypes of tubal ectopics—interstitial, isthmic, ampullar, and infundibular—refer to the portion of the tube in which implantation takes place. Ampullar implantation is most common, although the interstitial form has more serious clinical consequences. Early development of an EP is the same as that of a uterine pregnancy, but tubal pregnancy usually ends in abortion through the tube into the peritoneal cavity, or the trophoblast erodes the tubal wall, leading to tubal rupture. A typical presentation is amenorrhea of several weeks followed by bleeding and abdominal pain. It necessitates immediate surgical attention.

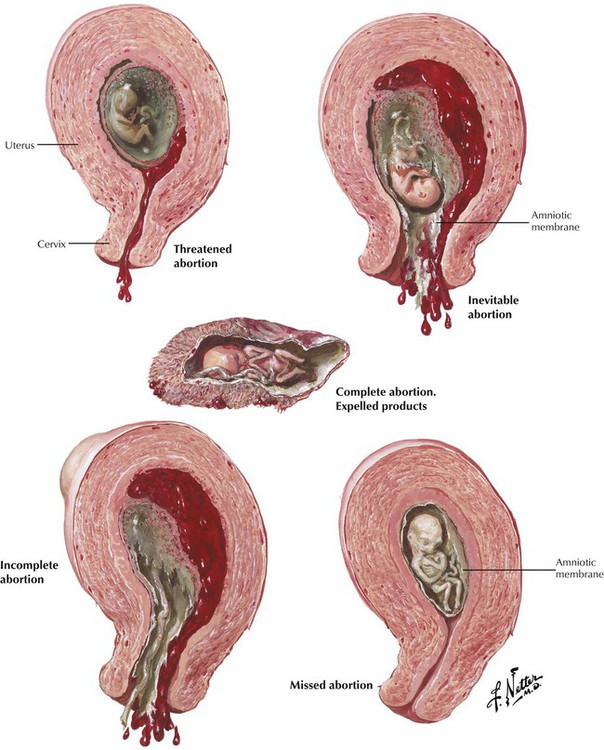

Abortion is the interruption of pregnancy in the first trimester before fetal viability. After viability, early end of pregnancy is called premature labor. Maternal or fetal factors, or both, may contribute to an abortion. Maternal factors include systemic infections and toxic agents in the maternal organism. Fetal factors include fetal malformations and congenital abnormalities. Rh incompatibility is an example of combined maternal and fetal factors. Signs and symptoms of abortion are vaginal bleeding followed by expulsive uterine contractions and cervical dilation. Abortion is complete when the entire fetus, placenta, and membranes are expelled and incomplete when the fetus is expelled but all or part of the placenta is retained in the uterus. In missed abortion, the fetus dies, but the placenta is not detached, and the fetus undergoes mummification. In the various types of inevitable abortion, the uterus must be completely evacuated to prevent recurrent hemorrhage and infection.

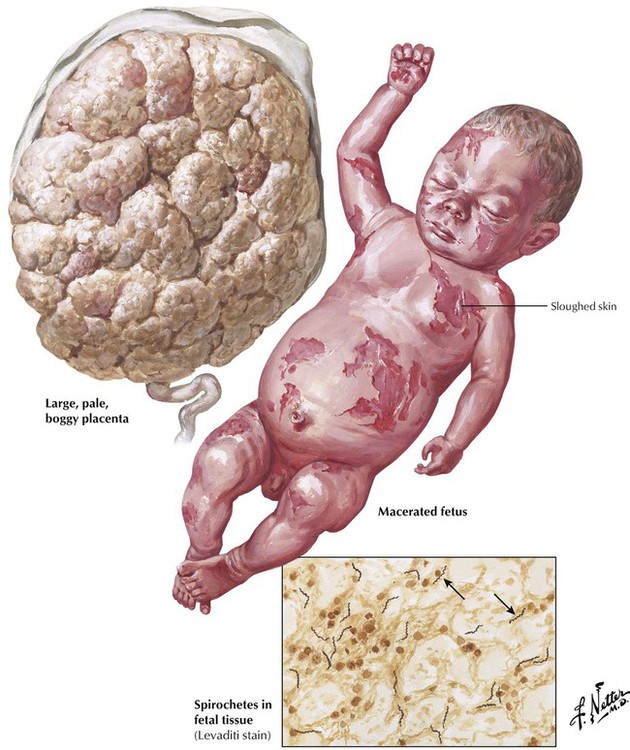

In various high-risk populations, syphilis remains a common cause of late fetal death. The fetus becomes infected through the placenta from the mother. At delivery, the placenta is enlarged, excessively lobulated, pale, and edematous. The cord and membranes are discolored and pale. Most syphilitic fetuses are born dead, but if the fetus is born alive, congenital syphilis soon becomes manifest. A syphilitic fetus is usually shorter than expected and has maceration of the skin. At autopsy, inflammatory and degenerative changes are usually present in the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and other organs. There is a characteristic osteochondritis with signs of disordered cartilage formation and endochondral ossification. Silver stains can reveal spirochetes of T. pallidum in fetal tissues and the placenta.

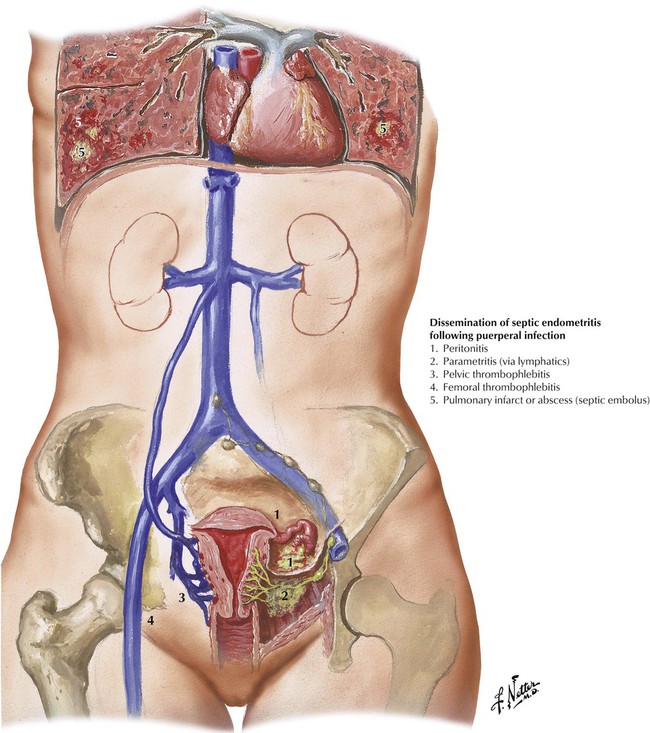

Puerperal infection is infection with various microorganisms of the birth canal in the postpartum period. Most cases of puerperal infection are caused by anaerobic and aerobic nonhemolytic varieties of streptococci. However, hemolytic streptococcus, introduced from the outside, is the most common cause of the fulminating and severe forms of puerperal infection. A similar pathophysiology is operative in nonpregnant women with toxic shock syndrome. Less common causes of puerperal infection are staphylococci and anaerobic and coliform bacteria. Blood loss and birth trauma are the most important predisposing factors for puerperal infection. Avoidable factors include faulty aseptic technique during labor and delivery. Endometritis may develop and give rise to puerperal sepsis. Pelvic thrombophlebitis as well as thrombophlebitis of the leg veins also may develop. Distant spread of infection from septic emboli may occur. Rapid diagnosis and antibiotic therapy can prevent a fatal outcome.

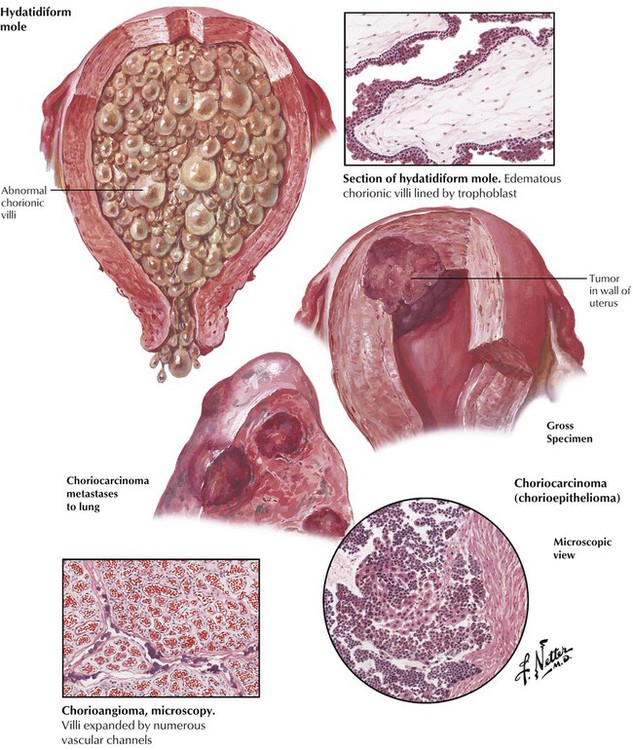

Hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma arise from trophoblastic tissues and cause rapid uterine enlargement, vaginal bleeding, and significantly increased urine and serum levels of human chorionic gonadotropic (HCG) hormone. Beginning as a pregnancy with a defective ovum, a hydatidiform mole is composed of abnormal chorionic villi that appear as grapelike clusters of vesicles and consist of branching structures covered with 2 or more layers of trophoblastic cells but lacking fetal blood vessels. Partial moles have embryo present and contain mixtures of normal and abnormal villi. Complete moles are composed entirely of abnormal villi with no identifiable embryo. A benign or malignant character to the mole is indicated primarily by the degree of cellular atypia of the villi. Choriocarcinoma (chorioepithelioma) is a rare but very malignant tumor composed of both syncytial and cytotrophoblastic cells arranged in a disordered pattern without forming chorionic villi. The neoplasm invades the uterine wall aggressively and metastasizes early, particularly to the lungs. Treatment includes evacuation of the contents of the uterus, surgery, and chemotherapy. Chorioangioma is a rare benign lesion.

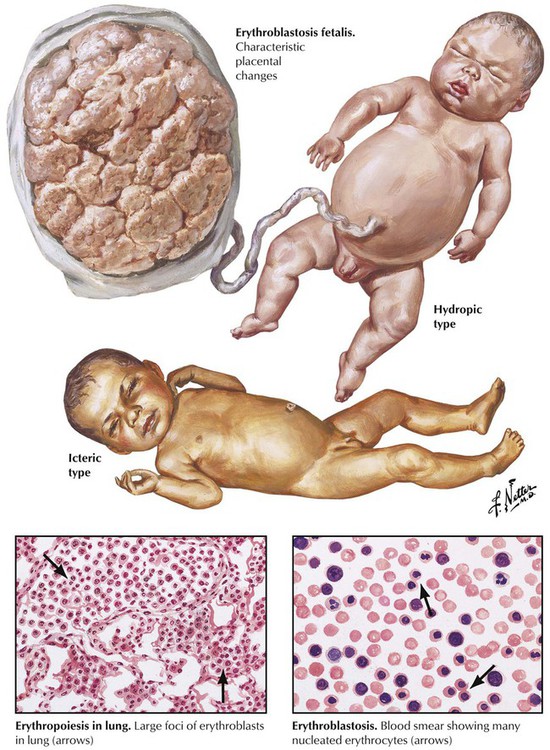

Erythroblastosis fetalis (hemolytic disease of the newborn) results from the progressive destruction of fetal erythrocytes by Rh factor antibodies produced by an Rh-negative mother (approximately 15%) and passed through the placental circulation to the fetus. Predisposing factors include transfusion or intramuscular injection of Rh-positive blood or carrying an Rh-positive fetus in utero. The major features of the disease are hemolytic anemia, icterus, and hydrops. Hydrops, the most severe form, results in an enlarged, boggy placenta and a macerated, stillborn infant. This must be distinguished from neonatal syphilis. The icteric type occurs in live infants with severe hemolytic anemia. In these infants, fetal blood contains many nucleated red blood cells, and the organs have prominent foci of extramedullary erythropoiesis. In less severe cases, anemia is milder, but the destruction of erythrocytes still leads to icterus and increased indirect bilirubin. Injection of Rh immune globulin to induce immunologic tolerance in the mother may prevent erythroblastosis fetalis.

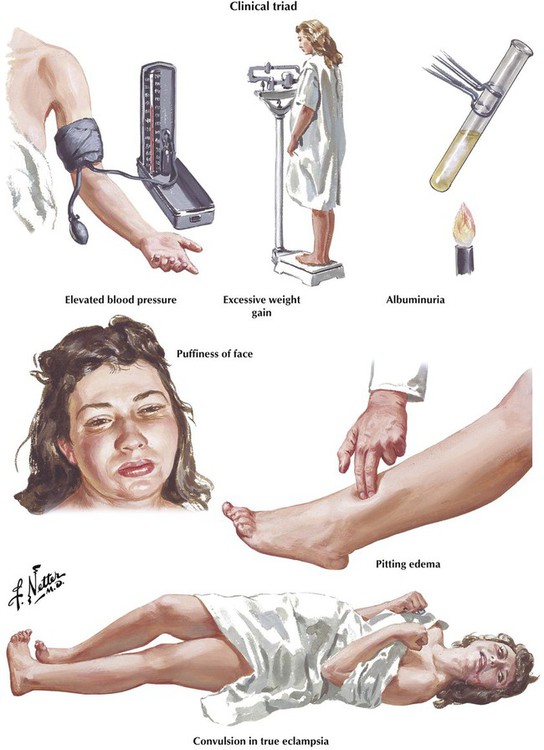

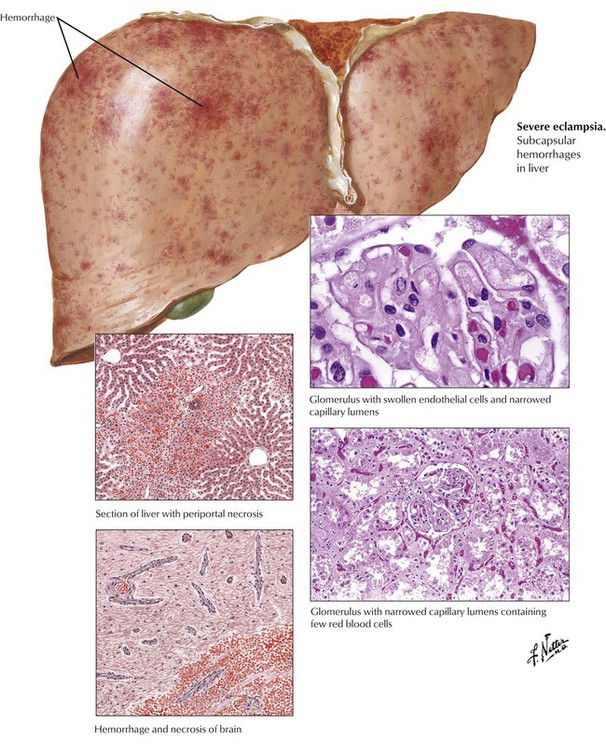

Toxemia of pregnancy is a generic term for a syndrome of pregnancy characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, and edema with the potential for convulsions or coma. Toxemia includes preeclampsia and eclampsia, and is distinct from essential hypertension associated with pregnancy. Acute toxemia develops during the third trimester of pregnancy—presenting as progressive weight gain, blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg, and proteinuria—and disappears promptly after delivery. Eclampsia is characterized by convulsions and coma, and these manifestations may develop independent of the magnitude of hypertension. Regular, prompt care is the key to prevention.

The pathologic effects of preeclampsia and eclampsia in various organs are qualitatively similar but vary in severity in relation to the clinical course. The liver and other organs can exhibit swollen and multiple foci of hemorrhage and necrosis. The most characteristic renal lesion consists of narrowing of the lumens of glomerular capillaries caused by thickening of the glomerular membranes due to endothelial cell swelling. Obstruction of blood flow through the glomerular tufts can lead to distal tubular necrosis. Bilateral cortical necrosis, a less common but severe lesion, is caused by severe vasoconstriction and necrosis of the intralobular arteries. The characteristic changes in the brain include edema, petechial hemorrhages, and, in severe cases, larger foci of hemorrhagic necrosis. All of this organ pathology is driven by vasoconstriction often complicated by microthrombosis due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

There is a close correlation between the occurrence of acute toxemia and conditions that predispose to a decrease in the maternal circulation to the placenta, the decidua, or both. Severe reduction of maternal blood flow causes true infarction of one or more of the placental cotyledons. True infarcts are found on the maternal aspect of the placenta, in contrast to other incidental placental lesions. Microscopically, the characteristic feature is necrotic chorionic villi. Acutely, the lesions are hemorrhagic infarcts that become pale as they age and heal without organization (i.e., without formation of granulation tissue and fibrosis). Placental ischemia is considered the major event in the pathogenesis of acute toxemia because it leads to increased production of angiotensin and other vasoconstrictors and decreased production of nitric oxide and other vasodilators. In turn, the placental ischemia may be caused by abnormal formation and implantation of the placenta (placentation).

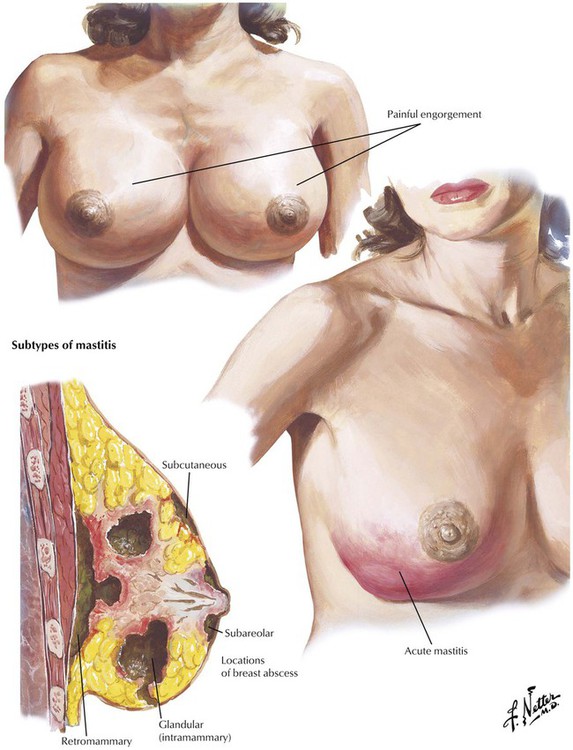

Painful engorgement of the breast usually occurs within the first few days postpartum, before the onset of lactation, or later when active lactation is interrupted. Because of vascular stasis, the breasts become engorged, firm, warm, and painful. Acute mastitis occurs during lactation after entry of infectious agents by way of a cracked or traumatized nipple, most commonly in primiparous women. The clinical manifestations are fever, leukocytosis, tenderness, and induration. There are 3 subtypes of mastitis: subareolar, glandular, and interstitial, the latter giving rise to a retromammary abscess. Rare infections of the breast, usually in nonpregnant women, are tuberculosis and syphilis with chancre formation.

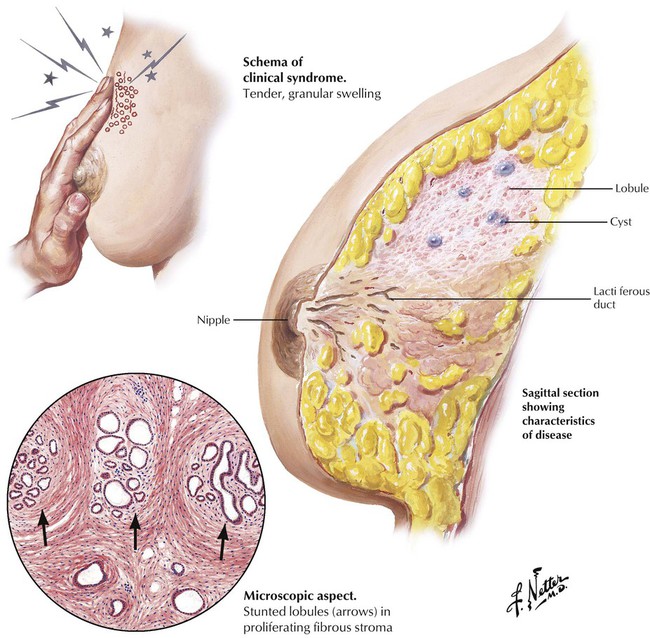

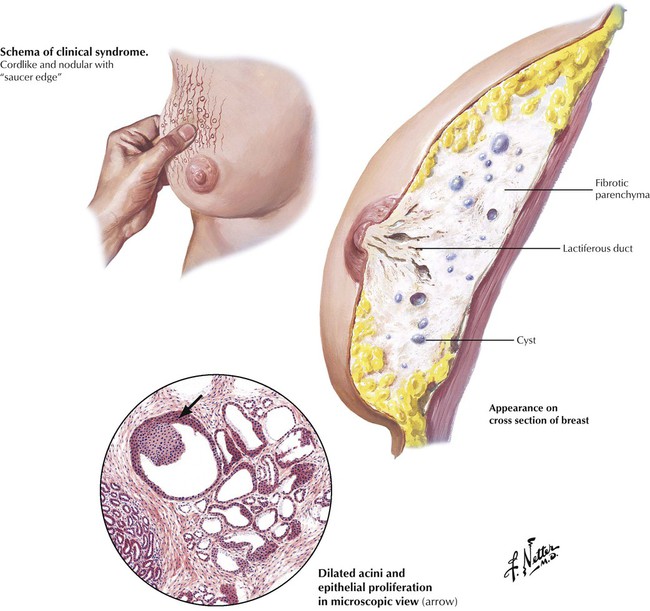

Chronic cystic disease or fibrocystic disease of the breast is a mammary disease complex with underlying endocrine disturbance, which comprises 3 principal types of abnormalities: cyst formation, often with apocrine metaplasia, fibrosis, and adenosis. True mastodynia, or intrinsic mammary pain, can be the first manifestation. Palpation typically reveals a swollen granular zone of increased density, which is most frequently located in the upper lateral quadrant, often bilaterally. On biopsy, the painful mammary tissue grossly is more dense and fibrous than normal, and histologically, the lobules are stunted or irregularly shaped, with small cystic dilatations, and they are surrounded by immature, proliferating connective tissue. The defective lobule formation relates to some disturbance of integrated action of the ovarian hormones on the mammary gland, increased estrogen production, inadequate progesterone secretion, or a combination of these.

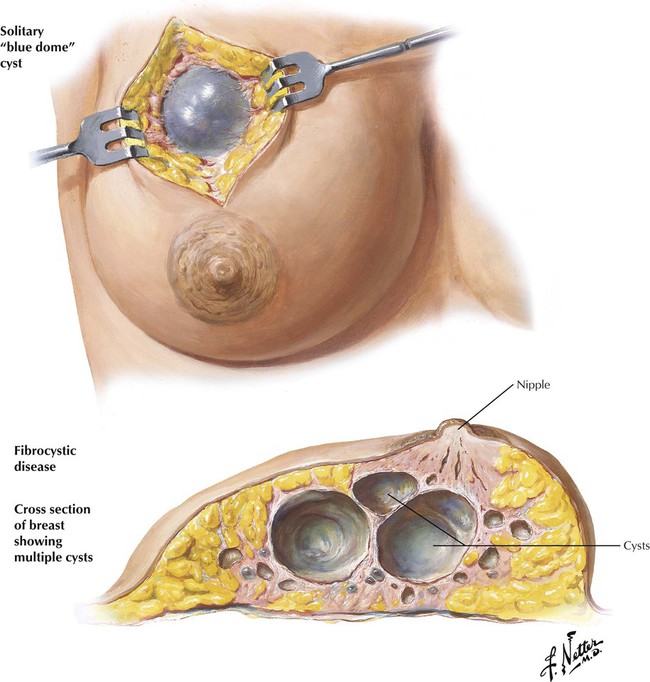

Some cases of fibrocystic disease are dominated by cystic changes. In some subjects, a single cyst of 1 to several centimeters in diameter develops. In other cases, the cysts are multiple, and often but not uniformly, both breasts are affected. The larger cysts have a characteristic blue dome, which bulges into the subcutaneous fat and contains cloudy straw-colored fluid, and a thin, fibrous wall, which may have an epithelial lining of duct cells. The cyst wall is embedded in dense, fibrous stroma. Multiple smaller cysts have similar features.

Adenosis is characterized by the development, in one or both breasts, of multiple nodules, varying from 1 mm to 1 cm in size and usually distributed about the periphery of the breast, creating a nodular breast with a saucerlike edge. The affected mammary tissue contains dense fibrous tissue, numerous cysts, and foci of epithelial proliferation. Lobule formation is considerably distorted. Some of the terminal tubules form solid plugs of basal cells, which, on cross section, appear as duct adenomas. Other tubules have greatly enlarged lobular structures, which are penetrated by dense strands of fibrous tissue, giving the appearance of an orderly proliferation of small ductules and acini, known as sclerosing adenosis. The incidence of cancer in patients with fibrocystic disease and accompanying ductal proliferative changes is approximately twice as high as is the incidence in the general female population.

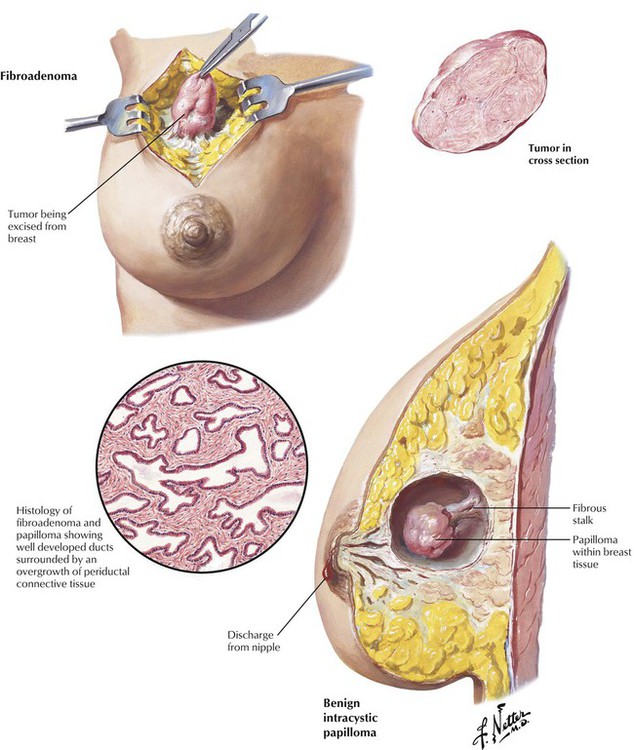

The fibroadenoma, the most common benign mammary tumor of the female breast, usually occurs in young adult women. The typical presentation is a firm, well circumscribed, nodular, freely movable, gradually enlarging mass. On excision, the tumor appears as a lobular mass and consists of well-developed ducts surrounded by marked overgrowth of periductal connective tissue. The growth of fibroadenoma is rapid in early adolescence, in pregnancy, or toward menopause, when estrogenic secretion is increased. Benign intracystic papillomas are fleshy epithelial growths occurring within a mammary duct or a dilated acinus, usually at or near menopause, in the central zone of the breast. They cause either a sanguinous discharge from the nipple or a lump associated with moderate tenderness. Intracystic papillomas are encapsulated tumors that contain branching epithelial projections and rest on a fibrous stalk. Multiple papillomas may occur in one or both breasts.

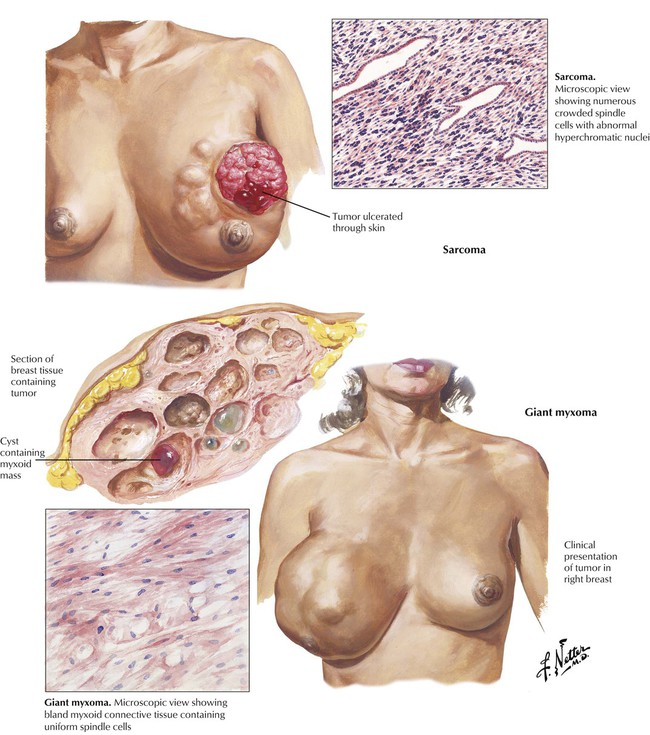

Giant mammary myxoma, also known as phyllodes tumor or cystosarcoma phyllodes, is a fibroadenoma that typically occurs near menopause and grows to large size. The tumors are heavy, massive, lobulated, fleshy growths with cystic areas; they remain encapsulated and moveable. Microscopically, the lesions are composed of myxomatous and fibrous connective tissue lined by epithelial cells and containing abundant stromal cells. Most of these tumors behave in a benign fashion. Mammary sarcoma is rare among the mammary tumors. Most of these sarcomas are fibrocellular lesions arising in the stroma of the breast or from the stroma of preexisting fibroadenomas. The lesions are characterized by rapid growth, large size, firm consistency, and, commonly, ulceration of the skin, with fungation of the mass.

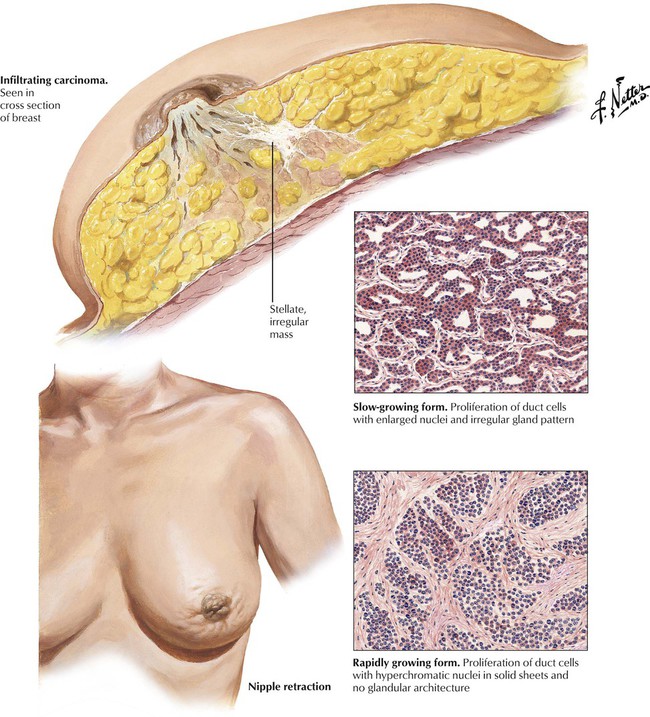

Approximately 15% to 30% of mammary carcinomas are in situ, and 70% to 85% are invasive. Approximately 80% of invasive lesions are infiltrating ductal carcinoma (scirrhus carcinoma or carcinoma simplex). They present as a palpable mass and may be associated with nipple retraction. Grossly, these are dense, yellowish-white, stellate, irregular masses with a gritty consistency. Microscopically, the tumor cells have a relatively uniform size; exhibit prominent, hyperchromatic nuclei; grow in small nests or cords; and are accompanied by growth of fibrous tissue producing the scirrhus feature of the lesions. Invasive lobular carcinoma (5-10% of breast carcinomas) tends to be multicentric in the same breast, to involve both breasts at a high frequency (approximately 20%), and to be hard to detect because of a diffusely invasive pattern. Prognosis is influenced by growth pattern of the tumor; degree of organization and cellular differentiation; expression of various gene products, including estrogen receptors and BRCA1 and BRCA2; and the presence of regional axillary lymph node and distant metastases.

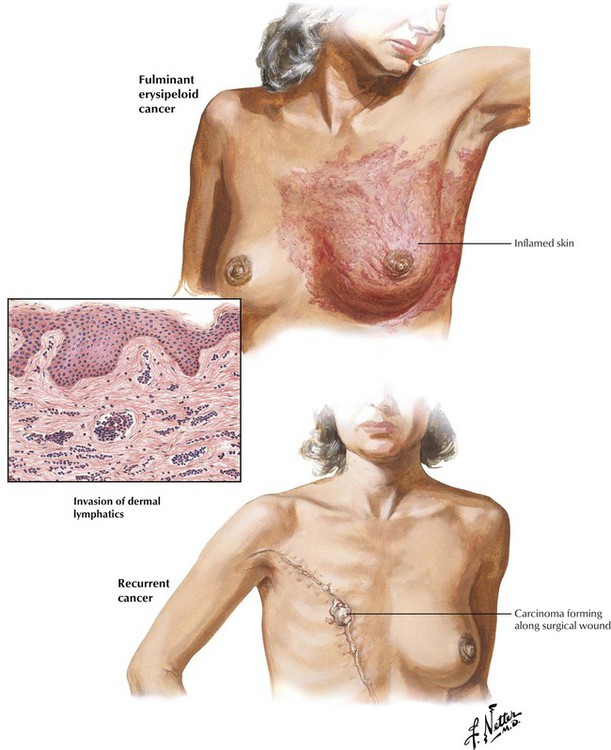

Inflammatory or acute fulminant carcinoma usually presents as a rapidly widening area of inflamed skin. The dermal inflammation usually correlates with retrograde spread of the cancer cells through the lymphatics of the skin. The skin is reddened, edematous, and rough, producing the characteristic orange peel effect. The carcinomatous spread is accompanied by a localized and systemic inflammatory process with low-grade fever, increased leukocyte count, and enlarged axillary lymph nodes. The most frequent site of local recurrence of breast cancer is the scar in the chest wall, followed by the axilla and the supraclavicular regions.

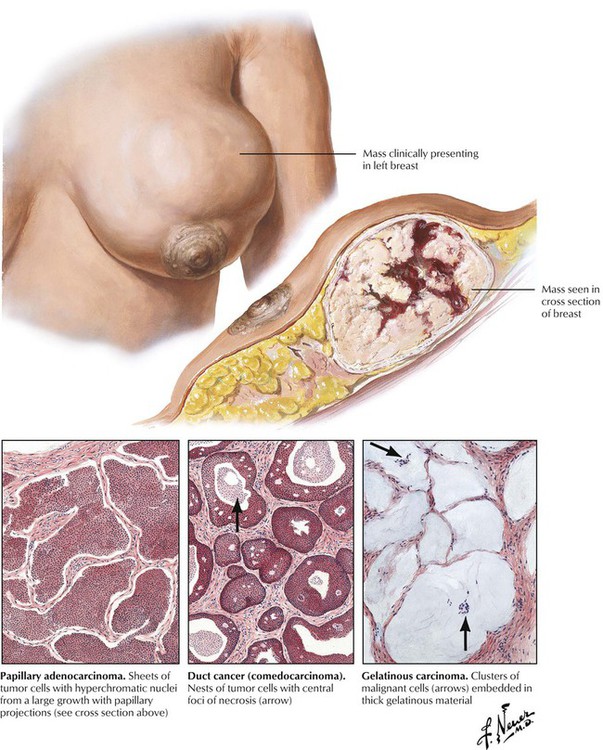

Approximately one fourth of mammary carcinomas have features of well-differentiated adenocarcinomas. These lesions include papillary adenocarcinomas, carcinomas with gelatinous, mucoid degeneration, and comedocarcinoma, a type of intraductal carcinoma that forms plugs and circumscribed rings of carcinoma cells in preexisting ducts. These lesions tend to bulge out from the breast rather than retract inwardly as with the infiltrating carcinomas. Skin and axillary node involvement occur much later in the course than with infiltrating scirrhous carcinoma. The tumors typically progress slowly and often reach large size. The majority are detected and removed by mastectomy before metastasis occurs. The lesions may have central foci of necrosis or hemorrhage.

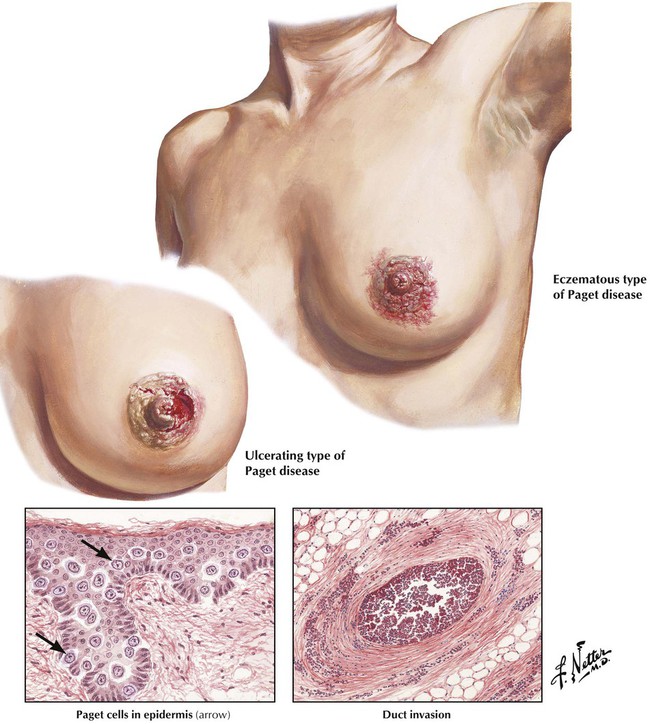

Paget disease of the nipple is produced by carcinomatous invasion of the nipple or areola and the mouths of the larger ducts by large malignant cells with hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei and pale staining cytoplasm. Usually, involvement of the nipple precedes the detection of a small primary tumor in the breast. The disease is occasionally bilateral. The involved nipple has a red granular or an exudating crusted appearance and eventually undergoes ulceration. Eventually, a hard mass, which is often associated with enlarged axillary lymph nodes, is palpable.