Chapter 649 Diseases of the Epidermis

649.1 Psoriasis

Clinical Manifestations

This common, chronic skin disorder is first evident in ≈ 30% of affected individuals within the first 2 decades of life. The lesions consist of erythematous papules that coalesce to form plaques with sharply demarcated, irregular borders. If they are unaltered by treatment, a thick silvery or yellow-white scale (resembling mica) develops (Fig. 649-1A). Removal of the scale may result in pinpoint bleeding (Auspitz sign). The Koebner, or isomorphic, response, in which new lesions appear at sites of trauma, is a valuable diagnostic feature. Lesions may occur anywhere, but preferred sites are the scalp, knees, elbows, umbilicus, superior intergluteal fold, and genitals. Small raindrop-like lesions on the face are common. Nail involvement, a valuable diagnostic sign, is characterized by pitting of the nail plate, detachment of the plate (onycholysis), yellowish brown subungual discoloration, and accumulation of subungual debris (Fig. 649-1B).

Guttate psoriasis, a variant that occurs predominantly in children, is characterized by an explosive eruption of profuse, small, oval or round lesions that morphologically are identical to the larger plaques of psoriasis (Fig. 649-1C). Sites of predilection are the trunk, face, and proximal portions of the limbs. The onset frequently follows a streptococcal infection; a culture of the throat and serologic titers should be obtained. Guttate psoriasis has also been observed after perianal streptococcal infection, viral infections, sunburn, and withdrawal of systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Treatment

The treatment of psoriasis should be viewed as a 4-tier process. The 1st tier is topical therapy. Topical corticosteroid preparations are effective. Mid-potency or stronger topical steroids are necessary (Chapter 638). The preparation that is least potent but effective should be applied twice a day. The topical vitamin D analog calcipotriene is also effective. Calcipotriene can burn and sting, limiting its usefulness in children. One commonly used strategy is to use calcipotriene twice a day on weekdays and a high- to super-potency topical steroid twice a day on weekends. Tazarotene, a topical retinoid, is also useful. It may be used alone or in combination with other topical modalities. Tar preparation and anthralin may also be used. For scalp lesions, applications of a phenol and saline solution (e.g., Baker Cummins P & S Liquid) followed by a tar shampoo are effective in the removal of scales. A high- to super-potency corticosteroid in a foam, solution, lotion, or gel base may be applied when the scaling is diminished. Nail lesions are difficult to treat but may respond to topical tazarotene.

Anstey A. Home UVB phototherapy for psoriasis. BMJ. 2009;338:1153-1154.

Bartlett BL, Tyring SK. Ustekinumab for chronic plaque psoriasis. Lancet. 2008;371:1639-1640.

Benoit S, Hamm H. Childhood psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:555-562.

Boehncke WH, Boehncke S, Schön MP. Managing comorbid disease in patients with psoriasis. BMJ. 2010;340:200-203.

Burden AD, Boon MH, Leman J, et al. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in adults: summary of SIGN guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c5623.

Cuchacovich RS, Espinoza LR. Ustekinumab for psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2009;373:605-606.

Duffin KC, Chandran V, Gladman DD, et al. Genetics of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: update and future direction. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1449-1453.

Griffiths CEM, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate to severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):118-128.

Kimball AB, Kupper TS. Future perspectives/quo vadis psoriasis treatment? Immunology, pharmacogenomics, and epidemiology. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:554-561.

Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-508.

Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG, et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:241-251.

649.2 Pityriasis Lichenoides

Clinical Manifestations

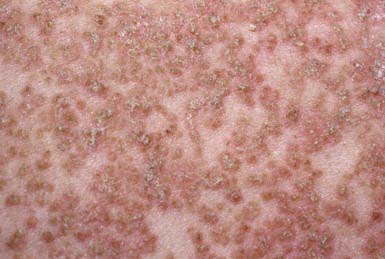

PLC manifests as generalized, multiple, 3- to 5-mm brown-red papules that are covered by a fine grayish scale (Fig. 649-2). Lesions may be asymptomatic or may cause minimal pruritus and occasionally become vesicular, hemorrhagic, crusted, or superinfected. Individual papules become flat and brownish in 2-6 wk, ultimately leaving a hyperpigmented or hypopigmented macule. Scarring is unusual. Lesions are most common on the trunk and extremities and generally spare the face, palmoplantar surfaces, scalp, and mucous membranes.

PLA manifests as an abrupt eruption of numerous papules that have a vesiculopustular and then a purpuric center, are covered by a dark adherent crust, and are surrounded by an erythematous halo (Fig. 649-3). Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, headache, and arthralgias may be present for 2-3 days after the initial outbreak. Lesions are distributed diffusely on the trunk and extremities, as in PLC. Individual lesions heal within a few weeks, sometimes leaving a varioliform scar, and successive crops of papules produce the characteristic polymorphous appearance of the eruption, with lesions in various stages of evolution. The overall eruption persists for months to years.

Khachemoune A, Biyumin ML. Pityriasis lichenoides: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:29-36.

Sotiriou E, Patsatsi A, Tsorova C, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:350-355.

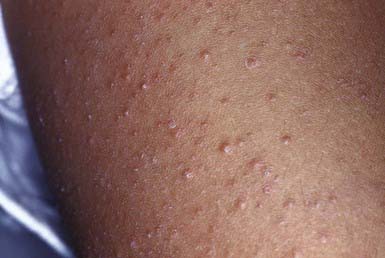

649.3 Keratosis Pilaris

Keratosis pilaris is a common papular eruption that may vary in extent from sparse lesions over the extensor aspects of the limbs to involvement of most of the body surface; typical areas of involvement include the upper extensor surface of the arms and the thighs, cheeks, and buttocks. The lesions may resemble gooseflesh; they are noninflammatory, scaly, follicular papules that do not coalesce. Irritation of the follicular plugs occasionally causes erythema surrounding the keratotic papules (Fig. 649-4). A subset of patients have keratosis pilaris associated with facial telangiectasia and ulerythema ophryogenes, a rare cutaneous disorder characterized by inflammatory keratotic facial papules that may result in scars, atrophy, and alopecia. Because the lesions of keratosis pilaris are associated with and accentuated by dry skin, they are often more prominent during the winter. They are more frequent in patients with atopic dermatitis and are most common during childhood and early adulthood, tending to subside in the 3rd decade of life. Mild or localized eruptions are treated with lubrication with a bland emollient; more pronounced or widespread lesions require regular applications of a 10-40% urea cream or an α-hydroxy acid preparation such as 12% lactic acid cream or lotion. Therapy may improve the condition but does not cure it.

649.5 Pityriasis Rosea

Clinical Manifestations

This benign, common eruption occurs most frequently in children and young adults. Although a prodrome of fever, malaise, arthralgia, and pharyngitis may precede the eruption, children rarely complain of such symptoms. A herald patch, a solitary, round or oval lesion that may occur anywhere on the body and is often but not always identifiable from its large size, usually precedes the generalized eruption. Herald patches vary from 1 to 10 cm in diameter; they are annular in configuration and have a raised border with fine, adherent scales. Approximately 5-10 days after the appearance of the herald patch, a widespread, symmetric eruption involving mainly the trunk and proximal limbs becomes evident (Fig. 649-5). When the disease is extensive, the face, scalp, and distal limbs may be involved; in the inverse form of pityriasis rosea, only those sites may be affected. Lesions may appear in crops for several days. Typical lesions are oval or round, <1 cm in diameter, slightly raised, and pink to brown. The developed lesion is covered by a fine scale, which gives the skin a crinkly appearance. Some lesions clear centrally and produce a collarette of scale that is attached only at the periphery. Papular, vesicular, urticarial, hemorrhagic, and large annular lesions are unusual variants. The long axis of each lesion is usually aligned with the cutaneous cleavage lines, a feature that creates the so-called Christmas tree pattern on the back. Conformation to skin lines is often more discernible in the anterior and posterior axillary folds and supraclavicular areas. Duration of the eruption varies from 2 to 12 wk. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly to severely pruritic.

Amer A, Fischer H, Li X. The natural history of pityriasis rosea in black American children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:503-506.

Browning JC. An update on pityriasis rosea and other similar childhood exanthems. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:481-485.

Gonzalez LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

649.6 Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Clinical Manifestations

This rare chronic dermatosis often has an insidious onset with diffuse scaling and erythema of the scalp, which is indistinguishable from the findings in seborrheic dermatitis, and with thick hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles (Fig. 649-6A). Lesions over the elbows and knees are also common (Fig. 649-6B). The characteristic primary lesion is a firm, dome-shaped, tiny, acuminate papule, which is pink to red and has a central keratotic plug pierced by a vellus hair. Masses of these papules coalesce to form large, erythematous, sharply demarcated orangish plaques, within which islands of normal skin can be distinguished, creating a bizarre effect. Typical papules on the dorsum of the proximal phalanges are readily palpated. Gray plaques or papules resembling lichen planus may be found in the oral cavity. Dystrophic changes in the nails may occur and mimic those of psoriasis.

649.7 Darier Disease (Keratosis Follicularis)

Etiology

A rare genetic disorder, Darier disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (ATP2A2 gene).

Clinical Manifestations

Onset usually occurs in late childhood. Typical lesions are small, firm, skin-colored papules that are not always follicular in location. The lesions eventually acquire yellow malodorous crusts; coalesce to form large, gray-brown, vegetative plaques (Fig. 649-7); and usually involve the face, neck, shoulders, chest, back, and limb flexures in a symmetric distribution. Papules, fissures, crusts, and ulcers may appear on the mucous membranes of the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, pharynx, larynx, and vulva. Hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and nail dystrophy with subungual hyperkeratosis are variable features. Severe pruritus, secondary infection, offensive odor, and aggravation of the dermatosis on exposure to sunlight may occur.

Differential Diagnosis

Darier disease is most likely to be confused with seborrheic dermatitis or flat warts.

649.8 Lichen Nitidus

Clinical Manifestations

This chronic, benign, papular eruption is characterized by minute (1-2 mm), flat-topped, shiny, firm papules of uniform size. The papules are most often skin colored but may be pink or red. In black individuals, they are usually hypopigmented (Fig. 649-8). Sites of predilection are the genitals, abdomen, chest, forearms, wrists, and inner aspects of the thighs. The lesions may be sparse or numerous and may form large plaques; careful examination usually discloses linear papules in a line of scratch (Koebner phenomenon), a valuable clue to the diagnosis because it occurs in only a few diseases. Lichen nitidus occurs in all age groups. The cause is unknown. Patients with lichen nitidus are usually asymptomatic and constitutionally well, although pruritus may be severe. The lesions may be confused with those of lichen planus and rarely coexist with them.

649.9 Lichen Striatus

Clinical Manifestations

A benign, self-limited eruption, lichen striatus consists of a continuous or discontinuous linear band of papules in a Blaschkoid distribution. The primary lesion is a flat-topped, red to violaceous papule covered with fine scale. Aggregates of these papules form multiple bands or plaques. In black patients, the lesions may be hypopigmented. The eruption evolves over a period of days or weeks in an otherwise healthy child, remains stationary for weeks to months, and finally remits without sequelae usually within 2 years. Symptoms are usually absent, although some children complain of itching. Nail dystrophy may occur when the eruption involves the posterior nail fold and matrix (Fig. 649-9).

649.10 Lichen Planus

Clinical Manifestations

This is a rare disorder in young children and uncommon in older ones. It is more often seen in children from the Indian subcontinent. The primary lesion is a violaceous, sharply demarcated, polygonal papule with fine lines or thin white scales on the surface. Papules may coalesce to form large plaques (Fig. 649-10). The papules are intensely pruritic, and additional papules are often induced by scratching (Koebner phenomenon) so that lines of them are often detected. Sites of predilection are the flexor surfaces of the wrists, the forearms, and the inner aspects of the thighs. Characteristic lesions of mucous membranes consist of pinhead-sized white papules that coalesce to form reticulated and lacy patterns on the oral mucosa and sometimes on the lips and tongue.

649.11 Porokeratosis

Clinical Manifestations

Porokeratosis is a rare, chronic, progressive disease. Several forms have been delineated: solitary plaques, linear porokeratosis, hyperkeratotic lesions of the palms and soles, disseminated eruptive lesions, and superficial actinic porokeratosis. Other types of porokeratosis are more common in males and begin in childhood. Sites of predilection are the limbs, face, neck, and genitals. The primary lesion is a small, keratotic papule that enlarges peripherally so that the center becomes depressed, with the edge forming an elevated wall or collar (Fig. 649-11). The configuration of the plaque may be round, oval, or gyrate. The elevated border is split by a thin groove from which minute cornified projections protrude. The enclosed central area is yellow, gray, or tan and sclerotic, smooth, and dry, whereas the hyperkeratotic border is a darker gray, brown, or black. The disease is slowly progressive but relatively asymptomatic. Malignant degeneration to squamous cell carcinoma has been reported in long-standing cases.

649.12 Papular Acrodermatitis of Childhood (Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome)

Clinical Manifestations

This distinctive eruption is occasionally associated with malaise and low-grade fever but few other constitutional symptoms. The incidence peaks in early childhood. Occurrences are usually sporadic, but epidemics have been recorded. The skin lesion is a monomorphous, usually nonpruritic, flat-topped, firm, dusky, or coppery red papule ranging in size from 1 to 10 mm (Fig. 649-12), although there is considerable variation in lesion type between patients. The papules appear in crops and may become profuse but remain discrete, forming a symmetric eruption on the face, buttocks, and limbs, including the palms and soles. The papules often have the appearance of vesicles; when opened, however, no fluid is obtained. The papules sometimes become hemorrhagic. Lines of papules (Koebner phenomenon) may be noted on the extremities. The trunk is relatively spared, as are the scalp and mucous membranes. Generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly (in patients with hepatitis B viremia) constitute the only other abnormal physical findings. The eruption resolves spontaneously in 15-60 days. Lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly, if present, may persist for several months. Elevation of serum transaminase and alkaline phosphatase values without concomitant hyperbilirubinemia is usual.

649.13 Acanthosis Nigricans

Clinical Manifestations

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by hyperpigmented velvety, hyperkeratotic, plaques that are most often localized to the neck, axillae (Fig. 649-13), inframammary areas, groin, inner thighs, and anogenital region. Acanthosis nigricans has classically been associated with obesity; drugs such as nicotinic acid; endocrinopathies, most commonly, diabetes mellitus and hyperandrogenic or hypogonadal syndromes; and genetic disorders caused by mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor genes. Acanthosis nigricans is found more commonly in African-American and Hispanic children. It is seen in >60% of children with a body mass index >98%. Although acanthosis nigricans is associated with malignancy in adults, this is rare in childhood.