CHAPTER 125 Diseases of the Anorectum

ANATOMY

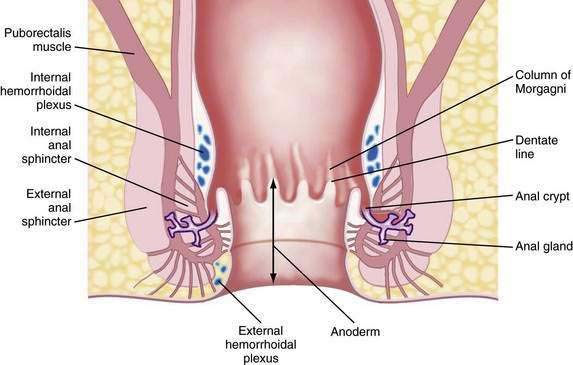

The functional anal canal is 3 to 4 centimeters long, beginning at the top of the anorectal ring (at the puborectalis sling) and extending down to the anal verge (anal orifice).1 The upper anal canal is lined mostly with columnar epithelium, a continuation of the same type of tissue that lines the rectum. Some squamous epithelium starts to be intermixed with the columnar epithelium in the rectum at about one centimeter above the dentate line. This change to squamous epithelium is gradual, and the area 1 to 1.5 cm proximal to the dentate line is termed the transitional zone.2 The dentate line is located in the mid-anal canal and is seen as a wavy line. Distal to the dentate line, the tissue is squamous epithelium, but it is unlike true skin because it has no hair, sebaceous glands, or sweat glands: it is commonly referred to as anoderm. The anoderm is thin, pale, and delicate, with the appearance of shiny, stretched skin. At the anal verge, the epithelium becomes thicker, and hair follicles begin to be seen (Fig. 125-1).3

Embryologically, the dentate line represents the junction between endoderm and ectoderm. Proximal to the dentate line, there is sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation; distally, the nerve supply is somatic.3 Therefore, above the dentate line, pain sensation is negligible; a biopsy can be done painlessly above the dentate line and without the need for local analgesia. Below the dentate line, however, the anoderm is highly sensitive, an important point to note when examining the anal canal or applying hemorrhoidal bands.

The arterial supply of the anal area is from the superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries, which are continuations or branches of the inferior mesenteric, hypogastric, and internal pudendal arteries, respectively. Blood flow is not uniform to the entire circumference of the anus and is relatively less posteriorly. This differential flow is an important factor in the role postulated for ischemia in determining the chronicity of anal fissure.4 The venous drainage from the anal canal is by both the systemic and portal systems. The internal hemorrhoidal plexus drains into the superior rectal veins, which drain into the inferior mesenteric vein and then into the portal vein. The distal part of the anal canal drains via the external hemorrhoidal plexus through the middle rectal and pudendal veins into the internal iliac vein (i.e., the systemic circulation).2

The lymphatic drainage of the anus changes at the dentate line. Proximally, the lymphatic vessels accompany the blood vessels and drain into the inferior mesenteric and periaortic nodes.1–3 Distal to the dentate line, the lymphatics drain into the inguinal nodes. Therefore, inguinal adenopathy can be seen with inflammatory and malignant disease of the lower anal canal.

Immediately proximal to the dentate line, the mucosa appears to have 6 to 14 pleats, called the columns of Morgagni. This configuration represents the funneling of the rectum as it narrows into the anal canal. Located at the base of the columns of Morgagni are anal crypts that lead to small rudimentary anal glands.3 These glands can extend through the internal anal sphincter; if their ducts are blocked, an anal abscess or fistula can develop (see Fig. 125-1).

The muscles surrounding the anal canal are important for maintaining fecal continence. The internal anal sphincter is the thickened continuation of the circular smooth muscle of the rectum. This muscle is involuntary and because it is composed of smooth muscle, it has a black hypoechoic appearance on anal ultrasonography. The internal sphincter ends above the external sphincter.3 The internal sphincter is important for passive continence, but partial division of the internal sphincter is possible without causing significant fecal incontinence. Division in the anterior or posterior position, however, can lead to stool leakage by creating an oval-shaped configuration in the distal anal canal, termed a keyhole deformity because the shape was reminiscent of the opening for the key in old-fashioned door locks.

The external anal sphincter is under voluntary control and is composed of a sheet of skeletal muscle arranged as a tube surrounding the internal sphincter. It appears as a broad cylinder with mixed echogenicity on anal ultrasound. Proximally, the external sphincter is fused with the puborectalis muscle, and distally, it ends slightly past the internal sphincter.1,3 Therefore, a groove can be palpated between the internal sphincter and external sphincter on digital examination, which is referred to as the intersphincteric groove. The puborectalis is U-shaped and forms a sling that passes behind the lower rectum and attaches to the pubis. Therefore, it is prominent laterally and posteriorly but absent anteriorly. The anorectal ring is palpable at the top of the anal canal, where the canal meets the rectum. It is composed of the puborectalis and the upper external and internal sphincters. The nerve supply to the external sphincter and puborectalis muscle is from the inferior rectal branch of the internal pudendal nerve (S2, S3, S4) and also from fibers of the fourth sacral nerve.1,3

EXAMINATION OF THE ANUS AND RECTUM

INSPECTION

Traction applied laterally to each side of the anal orifice with a gauze pad allows eversion of the distal anus for further inspection. This technique is particularly helpful in viewing a fissure without causing undue pain (Fig. 125-2). Some examiners stroke the perianal skin with a cotton-tipped applicator to look for reflex contraction of the anal muscles (anal wink, anocutaneous reflex) or check perianal sensation with a pinprick; these maneuvers give a crude determination of sphincter innervation and are important in evaluating for sensory neuropathies. The nearby skin of the buttocks, perivaginal region, base of the scrotum, and up to the tip of the coccyx should be viewed. Adenopathy in the inguinal region may be seen when certain infectious or neoplastic lesions are found distal to the dentate line.

ENDOSCOPY

The decision to perform endoscopy depends on the findings on history and physical examination. Endoscopy usually is necessary for the evaluation and exclusion of organic disease in patients with fecal incontinence, constipation, unexplained anal pain,5 anemia, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding.

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

The flexible sigmoidoscope is simply a shorter version of a colonoscope, measuring 60 cm in length. Most endoscopists use a gastroscope for sigmoidoscopy because it is thinner, better tolerated by the patient than a sigmoidoscope or colonoscope, and easier to maneuver. One to two enemas are given before the examination and sedation typically is not used, which is the reason patients who have undergone both colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy report that the latter was more difficult.6 The goal is to examine the left colon, which should be reached at least 80% of the time.7 Lesions can be biopsied, but the presence of polyps mandates full colonoscopy after a bowel preparation to exclude synchronous polyps or cancer. The use of electrocautery and argon plasma coagulation should be avoided during sigmoidoscopy, even if enemas have just been given and the preparation appears optimal, because intracolonic bowel explosions have occurred from ignition of bowel gas that has passed from the stool-containing proximal colon distally to the operative site.8

HEMORRHOIDS

Hemorrhoids are perhaps the most misunderstood anorectal problem for patients and physicians alike. In clinical practice, patients use the term hemorrhoid to describe almost any anorectal problem, from pruritus ani to cancer.9 In fact, hemorrhoids are a normal part of human anatomy,10,11 in contrast to hemorrhoidal disease, which is manifested by prolapse, bleeding, and itching.10 Hemorrhoids are dilated vascular channels located in three fairly constant locations: left lateral, right posterior, and right anterior. Internal hemorrhoids originate above the dentate line and are covered with columnar or transitional mucosa. External hemorrhoids are located closer to the anal verge and are covered with squamous epithelium. Traditionally, internal hemorrhoids are classified into four grades: first-degree hemorrhoids, which bleed with defecation; second-degree hemorrhoids, which prolapse with defecation but return spontaneously to their normal position; third-degree hemorrhoids, which prolapse through the anal canal at any time, but especially with defecation, and can be replaced manually; and fourth-degree hemorrhoids, which are prolapsed permanently.11 Although the exact incidence of hemorrhoidal disease is unknown, it is thought to be present in 10% to 25% of the adult population.12

INTERNAL HEMORRHOIDS

Symptoms and Signs

It is speculated that internal hemorrhoids become symptomatic when their supporting structures become disrupted and prolapse of the vascular cushions occurs.13 Hemorrhoids occur more commonly in people with constipation who have hard, infrequent stools.14 They also can occur in patients who have frequent loose stools or if prolonged periods of time are spent sitting on the toilet, leading to vascular congestion. Bleeding is typically painless and the patient describes bright red blood usually seen on the toilet tissue, dripping into the toilet bowl, or streaking the outside of a hard stool. If the bleeding is more substantial, the blood can accumulate in the rectum and be passed later as dark blood or clots.11 If the patient has chronic hemorrhoidal prolapse, blood or mucus might stain the patient’s underwear, and the mucus against the anal skin might lead to itching.10

Treatment

Treatment is based on the grade of the hemorrhoids. Grade 1 and some early grade 2 internal hemorrhoids usually respond to manipulation of the diet, along with avoidance of medications that promote bleeding, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A high-fiber diet, with 20 to 30 g of fiber daily introduced gradually into the diet, should be accompanied by six to eight glasses of nonalcoholic, noncaffeinated fluid daily. Patients are encouraged to read the package regarding the amount of fiber per serving; for instance, a bowl of raisin bran cereal can have eight grams of dietary fiber per serving whereas a similar portion of corn flakes has only one gram.15 Fiber supplementation with psyllium or hydrophilic colloid may be added to achieve the optimal amount of daily fiber, if the patient’s daily dietary fiber is insufficient. In my experience, patients who can achieve adequate dietary fiber intake without supplements have better long-term relief of hemorrhoidal disease with dietary change than those who need daily supplementation.

Patients are urged to avoid straining during defecation and reading while on the toilet. Excessive scrubbing of the anus when showering or bathing or excessive wiping after a bowel movement is discouraged. Most over-the-counter agents are not efficacious, even though many patients report some relief of their symptoms with use of these products.14 Sometimes a stool softener such as docusate sodium or a lubricant such as mineral oil can be prescribed if the stool is hard and does not respond to increased intake of fiber and fluid; laxatives and enemas rarely are needed.15 Even patients who require more-aggressive treatment of their hemorrhoids should be advised to increase their dietary fiber and fluids and to avoid straining during defecation to prevent recurrence after treatment.

Sclerosing Agents

Injection therapy for hemorrhoids has been practiced for more than 100 years. The goal is to inject an irritant into the submucosa above the internal hemorrhoid at the anorectal ring (the area that does not have somatic innervation) to create fibrosis, tack down the hemorrhoid and prevent hemorrhoidal prolapse.16 Usually less than one milliliter of sclerosant is needed to create a raised area. Many substances have been used, but sterile arachis oils containing 5% phenol are the most popular.16 This approach usually is advocated for first- and second-degree hemorrhoids.

Sclerotherapy can produce a dull pain for up to two days after injection. A rare but severe complication is life-threatening perineal sepsis, which can occur three to five days after injection and usually is manifested by any combination of perianal pain or swelling, watery anal discharge, fever, leukocytosis, and other signs of sepsis. Prompt surgical intervention and intravenous antibiotics are mandatory.16,17 Approximately 75% of patients with second-degree hemorrhoids improve after injection therapy.18

In patients with active acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), injection therapy may be favored over surgical treatments because of concerns about the patient’s poor overall general condition. There also may be problems with wound healing for these patients, but successful treatment of second-, third-, and fourth-degree hemorrhoids without complications has been reported in patients with AIDS,19 some of whom did require repeat treatment to manage persistent symptoms.

Rubber Band Ligation

Rubber band ligation (RBL) has become the most common office procedure for the treatment of second- and third-degree hemorrhoids.20 Generally, this approach cannot be used with first-degree hemorrhoids, because there is insufficient tissue to pull into the bander; this treatment is not appropriate for fourth-degree hemorrhoids.18

Rubber bands are applied to the hemorrhoidal complex and rectal mucosa just proximal to the internal anal cushion. To avoid severe pain, bands are never placed below the dentate line, which is innervated by somatic fibers. The number of bands that can be safely placed in one setting remains controversial. Several studies have shown that triple RBL is safe and effective at one sitting,20,21 but many authorities believe that the severity of pain and risk of complications are less if one band is applied per visit. I typically place a single band at the first visit, and if that is well tolerated, I place two bands during the next and subsequent visit. Most grade 2 or 3 hemorrhoids can be managed successfully with two or three RBL procedures.

Major complications from RBL include bleeding, sepsis, cellulitis, and death. Bleeding when the band and necrotic hemorrhoidal tissue comes off four to seven days after application may be severe and even life-threatening; severe bleeding occurs in about 1% of patients21 and usually can be tamponaded by placing a large-caliber Foley catheter in the rectum, filling the balloon with 25 to 30 mL or more of fluid, and pulling the balloon tightly against the top of the anal ring. If this approach fails, epinephrine can be injected at the bleeding site, but sometimes a suture is required to stop the bleeding.

A more serious complication is sepsis. There have been five recorded deaths, two additional patients with life-threatening sepsis, and three cases of severe pelvic cellulitis following RBL of hemorrhoids.17 The onset of sepsis usually is two to eight days after RBL in otherwise healthy people. New or increasing anal pain, sometimes radiating down the leg, or difficulty voiding may be the first indications of a life-threatening infection. Immediate intravenous antibiotics and surgical débridement are required.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy freezes tissue, thereby destroying the hemorrhoidal plexus. Once a popular treatment, its use has declined because of the profuse, foul-smelling discharge resulting from tissue necrosis. The procedure also can be painful, and healing can be prolonged.22

Infrared Photocoagulation

Infrared photocoagulation uses infrared radiation to coagulate the tissue, leading to fibrosis. The device is applied for 1.5 seconds in two or three sites proximal to the hemorrhoidal plexus. Reported results for first- and second-degree hemorrhoids are as good as those reported for RBL or sclerotherapy.18 One study reported a 10% relapse rate at three years in patients who had third-degree hemorrhoids and were treated with RBL at recurrence.23 Pain and other complications are rare with infrared photocoagulation. This technique also can be useful when there is a small amount of residual friable hemorrhoidal tissue that cannot be banded, either because there is too little tissue to be incorporated into the band or the tissue is too distal to be safely banded without causing discomfort. In my opinion, this technique generally is less effective than RBL.

Surgical Therapy

Based on the common finding of increased resting anal canal pressure in patients with hemorrhoids,24 methods to reduce internal anal sphincter pressure in these patients, including internal sphincterotomy and manual dilation of the anus (Lord’s procedure) had been advocated in the past; today, these procedures are mainly of historical interest. One study of the Lord procedure to treat second- and third-degree internal hemorrhoids with a median follow-up of 17 years found a nearly 40% recurrence rate and a 52% rate of incontinence.25 Lateral internal sphincterotomy occasionally is performed if patients are found to have both a fissure and extensive hemorrhoids at the time of surgery for hemorrhoids.

Hemorrhoidectomy is the surgical procedure of choice for fourth-degree and some third-degree hemorrhoids and rarely is needed for first- or second-degree hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoidectomy can be done with local, regional, or general anesthesia. Whether the edges of the mucosa are closed or left open after excision of the hemorrhoidal tissue is a matter of preference, because results and severity of postoperative pain are similar with both approaches.26 In one of the few long-term studies of hemorrhoidectomy, recurrent hemorrhoids were found in 26% at a median follow-up of 17 years,25 but only 11% of patients needed an additional procedure.

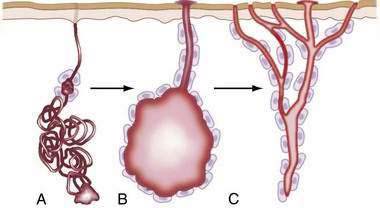

Postoperative pain is the major drawback of hemorrhoidectomy. In an effort to reduce postoperative pain, topical and oral metronidazole have been used with success, although the mechanism of this action is not known.27 Additionally, a new procedure was introduced in 1998 by Longo,28 in which a circular stapler is used to fix the anal cushions in their correct positions. The mucosa is excised circumferentially just above the anorectal ring, thereby interrupting the vascular supply to the cushion (Fig. 125-3). This procedure is called the procedure for prolapse of hemorrhoids (PPH) or stapled hemorrhoidopexy. It is used for third- and fourth-degree hemorrhoids. Results of the randomized multicenter U.S. experience, which compared PPH with traditional excisional hemorrhoidectomy, showed that PPH-treated patients experienced significantly less pain.29 Another study comparing PPH with RBL found patients reported more pain and an increased risk of postoperative bleeding with PPH; however, more patients in the RBL group required excisional hemorrhoidectomy for persistent symptoms.30

PPH can have significant postoperative complications, of which bleeding and urinary retention are most common.29 Severe persistent postoperative pain occurs in one third of patients and may be related to placing the staple line too close to the dentate line.31 Additionally, defecation urgency can be persistent in up to 28%. Perhaps the most feared complication is pelvic sepsis leading to death.32 Several studies analyzing the long-term results of the prospective randomized studies comparing excisional hemorrhoidectomy and PPH suggest a higher rate of recurrent hemorrhoidal symptoms in the PPH group.33–34 Further long-term studies are needed to define the durability of the PPH procedure.

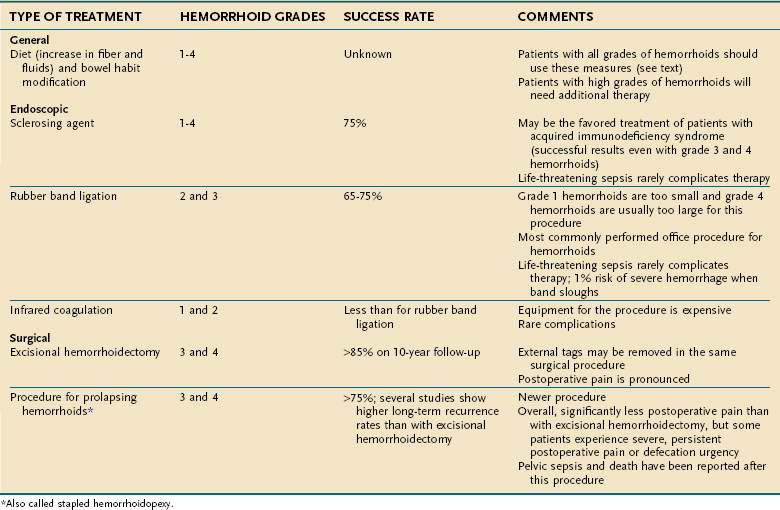

Table 125-1 summarizes the treatment options for internal hemorrhoids.

EXTERNAL HEMORRHOIDS AND ANAL TAGS

Symptoms and Signs

External hemorrhoids can be associated with acute pain from thrombosis.13 The level of pain is variable, but patients might notice a rapidly increasing throbbing or burning pain accompanied by a new lump in the anal region. Sometimes the lump has a bluish discoloration caused by the clot. With time, a small area of necrosis can form over the lump, followed by extrusion of the clot, with relief of the pain.

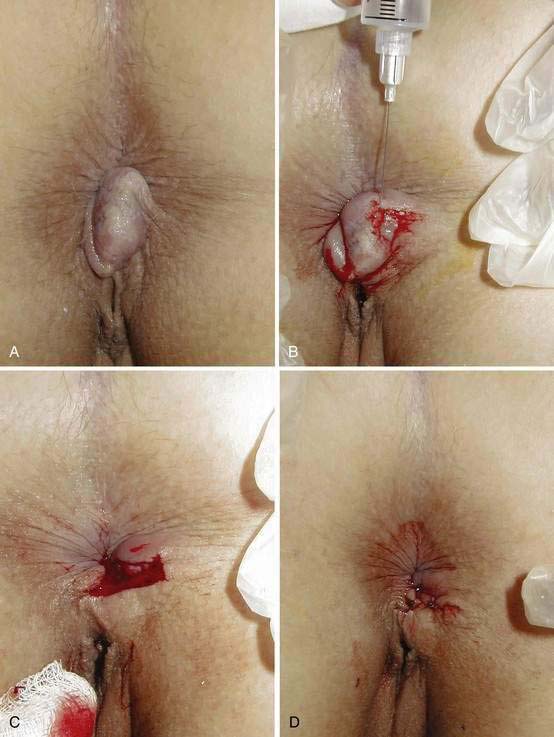

Treatment

Treatment of thrombosed hemorrhoids depends on the associated symptoms. With time, the pain associated with the acute thrombosis subsides. If the patient has minimal or moderate pain, sitz baths and analgesics are prescribed. For severe pain, the clot is removed under local anesthesia. Because of the high rate of recurrence with simple enucleation alone, most surgeons recommend excising the entire thrombosis and overlying skin. This procedure also can be done in the office with scissors and local anesthesia (Fig. 125-4).35 The skin edges may be closed or left open to heal by second intention.

Another successful therapy has been topical application of 0.3% nifedipine cream.36 It is speculated that the success of nifedipine cream in reducing pain from thrombosed hemorrhoids results from its anti-inflammatory and smooth muscle-relaxing properties. Its use can preclude the need for surgery.

Special Considerations

Large, edematous, shiny perianal skin tags should alert the physician to the possibility of Crohn’s disease. These tags can have a waxy bluish discoloration (Fig. 125-5), are often tender, and are best described as “funny looking.” Careful history taking for symptoms of Crohn’s disease is indicated, and further testing is needed if there is any suspicion that the tags are other than ordinary. Surgical excision of these Crohn’s disease tags is to be avoided in almost every situation, because after surgery the patient usually is left with unhealed anal ulcers.

Figure 125-5. Anal skin tags associated with perianal Crohn’s disease. Note the waxy bluish appearance of the tags.

Patients who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) usually are treated as if they do not carry HIV, unless their immune status is significantly compromised. Previously mentioned was the use of sclerotherapy in this population.19 In another study of 11 HIV-positive men with a mean CD4+ count of 420 cells/mm3 and a mean follow-up of six months, no complications occurred after RBL of hemorrhoids, and symptoms improved in all.37

ANAL FISSURE

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of a chronic anal fissures is unknown. Using laser Doppler flowmetry, it has been shown that the posterior area of the anoderm is less well perfused than other areas of anoderm. There is speculation that increased tone in the internal sphincter muscle further reduces the blood flow to this area, especially in the posterior midline.4 Based on these findings, fissures are thought to represent ischemic ulceration.38 Trauma during defecation, especially with passage of a hard stool or explosive diarrhea, is believed to initiate formation of a fissure.

SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND DIAGNOSIS

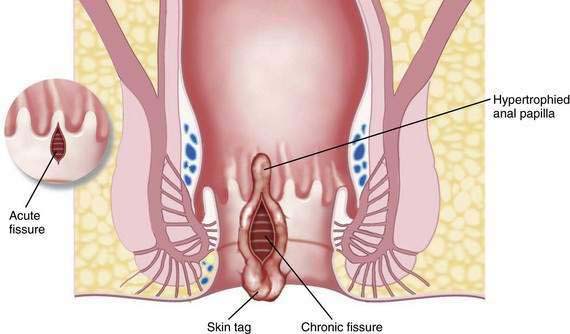

Fissures can be acute or chronic. Acute fissures are simply a split or crack in the anoderm without exposed internal sphincter fibers. Chronic fissures show rolled edges, fibrosis of the edges, deep ulceration with exposure of the underlying internal sphincter muscle, enlargement of the tissue at the dentate line (hypertrophied anal papilla), and edematous skin tags at the distal anal verge (see Fig. 125-2; Fig. 125-6).

TREATMENT

Treatment of acute and chronic anal fissures (Table 125-2) starts with modification of the diet similar to the conservative treatment of hemorrhoids described previously. Patients follow a high-fiber diet with fiber supplements, and they increase their fluid intake. Soaking in a sitz bath or warm tub relaxes the sphincter and can provide significant relief.13 If needed, stool softeners are added. Acute fissures respond better to these measures than do chronic fissures, but such treatment is still a critical component to the management of a chronic fissure.

| TREATMENT | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Acute | |

| Increase oral fluids, high-fiber diet, fiber supplements, sitz baths, and stool softeners if needed | |

Medical Therapy

The traditional surgical treatment of chronic anal fissure, lateral internal sphincterotomy, has come under intense scrutiny since the 1990s. Because of concerns about fecal incontinence, pharmacologic therapy has gained popularity. One of the initial treatments was topical nitroglycerin ointment applied to the anal region. A pea-sized amount of 0.2% to 0.4% nitroglycerin ointment with gradual escalation of the dose applied three times daily is the most common way to use the medication. Headache is a significant adverse complaint,39 and a gradual increase in dose might reduce this drawback. Patients should be cautioned to wear a finger cot or surgical glove when applying the ointment to prevent absorption through the digital skin. Despite early successful clinical trials, long-term success rates have been questioned. A large systematic review found that healing of fissures with nitroglycerin was only marginally better than with placebo.39 One randomized trial found overall healing in about only one third of patients at six months.40

Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine and diltiazem) have been advocated because of their ability to relax the internal anal sphincter. Although these topical agents have been studied, far fewer studies are published for them than for nitroglycerin. Topical 2% diltiazem gel has been used to treat nitroglycerin-resistant anal fissures. In one study of 39 fissures unhealed by nitroglycerin, 49% were healed at eight weeks after use of diltiazem gel.41 This treatment modality generally is preferred to nitroglycerin because it does not commonly cause headaches, which are often seen with topical nitroglycerin. Topical 2% diltiazem, applied two to three times daily, is my preferred topical treatment for a chronic anal fissure.

The injection of botulinum toxin A, which inhibits acetylcholine release, into the internal sphincter close to a fissure, was described first by Jost and Schimrigk in 1993.42 Since then, this modality has gained popularity as a treatment for chronic anal fissure. In a study from Italy, 73% of anal fissures were healed at eight weeks,43 with no recurrences a mean of 16 months later. In one study comparing botulinum toxin injection with topical nitroglycerin ointment, at eight weeks, fissures were healed in 96% of patients injected with botulinum toxin and in 60% of those treated with nitroglycerin. In neither group was there a recurrence at a mean follow-up of 15 months.44 Comparison of botulinum toxin with lateral internal sphincterotomy showed that at one year, more fissures were healed after surgery (94%) than with the injection (75%).45 Long-term results, however, might not be as optimal as hoped with botulinum toxin injection. In one study of 57 patients, only 22 (41%) had healed fissures a median of 42 months after botulinum injection.46 Two meta-analyses comparing botulinum toxin to lateral internal sphincterotomy demonstrated that long-term healing was better with surgery but that side effects and complications were far less with botulinum toxin injection.47,48

Surgical Therapy

The standard treatment for chronic anal fissures has been lateral internal sphincterotomy, and it remains the standard by which all other treatments must be measured.49 One long-term study found that among 2108 patients with anal fissures who underwent outpatient surgery with local anesthesia and intravenous sedation, the results were very good to excellent in 96% at a follow-up of 4 to 20 years. The rate of recurrent fissures was 1%. Permanent incontinence did not occur.49 When performed correctly, lateral internal sphincterotomy still appears to be superior (and probably cheaper in the long term) to any currently available medical treatment.50,51

Special Considerations

Postpartum women require special consideration. In one study, painful fissures developed in 29 (9%) of 313 primigravid women in the immediate postpartum period. Anal sphincter hypertonia was not seen in these patients,52 and because vaginal delivery is associated with anal trauma, division of the anal sphincter in this setting may be detrimental. Of the 29 fissures, 27 healed with medical treatment. The researchers suggested that if surgical intervention is needed in a postpartum woman with an anal fissure, an advancement flap (which raises a flap of healthy tissue to cover the open area) may be preferable to a lateral sphincterotomy.53

ABSCESSES AND FISTULAS

ABSCESSES

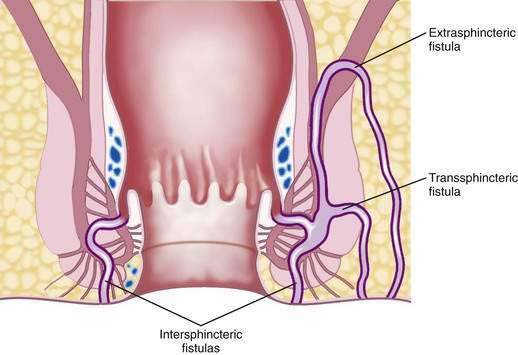

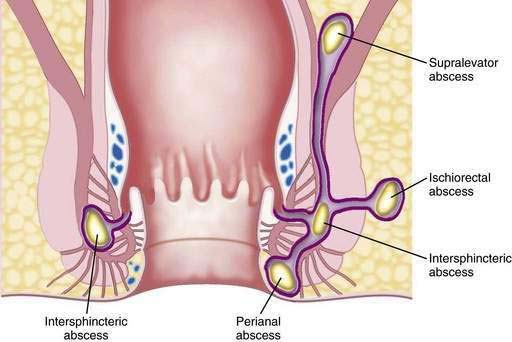

Because nearly all of the anal glands terminate in the intersphincteric plane, abscesses tend to originate in the intersphincteric space, from where they can travel up, down, or circumferentially around the anus. Abscesses are classified according to where they extend, and may be perianal, ischiorectal, intersphincteric, or supralevator (Fig. 125-7). The most common type is the perianal abscess (40% to 50%), and the least common type is the supralevator abscess (2% to 9%).54

Figure 125-7. Schematic depiction of the classification of abscesses of the anal region based on their location.

The diagnosis of anorectal abscess is based on typical symptoms and signs. Swelling, throbbing, and continuous pain are the most common symptoms. On examination, erythema, swelling, and marked tenderness may be present. If the abscess is in the intersphincteric space, however, there may be no abnormal findings externally. Nevertheless, a digital examination may be impossible because of pain, or a boggy area may be felt over the internal anal sphincter adjacent to the abscess. An ischiorectal abscess produces pain in the buttock, but no abnormality may be appreciated on examination. The ischiorectal space is a potential space that can be large, and pus can move upward rather than toward the skin.54 Symptoms of a supralevator abscess may be intra-abdominal or urinary, and patients can have lower abdominal discomfort and urgency without any anorectal complaints or clinical findings. If the patient cannot be evaluated because the pain is severe or if no abnormality is found on examination, the patient should undergo an examination under anesthesia.

FISTULA-IN-ANO

Treatment of fistula-in-ano is surgical intervention. The course of the fistulous tract influences the type of surgical treatment (Fig. 125-8). The most common treatment is a fistulotomy, or unroofing of the tunnel. Fistulotomy should not be performed if the tract traverses a substantial portion of the external sphincter, in which case its division will result in incontinence. Fistulas that are appropriate for fistulotomy can be unroofed, however, and the base curetted and allowed to heal from the bottom up. The cure rate for uncomplicated fistulas not associated with Crohn’s disease approaches 100%.

A fistula that involves a substantial portion of the anal sphincter requires special treatment to avoid incontinence. The options are transanal advancement flap, skin advancement flap, fibrin glue injection, or collagen plug insertion. Transanal advancement flaps are a common surgical repair for these complex fistulas. Although initial success rates were higher, more-recent studies found success rates varying from 67% to 77%.55,56 Rates of incontinence after a flap repair range from 9% to 35%.55–57 Alterations in continence tend to occur more often in patients older than 50 years.57

Fibrin adhesive made from commercial fibrin sealant has been used to close anal fistulas. The durable healing rate for cryptoglandular fistula was 23% in one study.58 Other studies, however, have reported rates of 59% to 92%,59,60 and most groups now report a long-term success rate of less than 33%. The fistulous tract is curetted aggressively, and the fibrin product is injected via the external opening until it is seen to emerge in the anal canal. Few complications have been reported with this method, and continence should not be affected. Retreatment for failures can be successful. The tract must be at least one centimeter long to allow sufficient length for the fibrin plug to adhere to the tract. This technique however, for the most part has been replaced by a collagen-plug technique because of high failure rates.

An anal fistula plug made from collagen has been used increasingly since the turn of the century. In the initial report by Armstrong, healing occurred in 38 of 46 (83%) patients, with a median follow-up of 12 months.61 However, in 2008, five other groups reported short-term success in only 30% to 60% of patients.62–66 My success rate is approximately 50% (Fig. 125-9). Although these later published results are disappointing, they are still improved over the results of fibrin glue injection, and the procedure is being used widely in the United States.

Direct closure of the internal opening of a trans-sphincteric fistula also has been reported, and in one series of 106 patients only seven had persistent fistula, for an overall closure rate of 93.4%67; 24 of the 106 patients, however, did require more than one operative procedure to obtain definitive fistula closure. This technique is not widely used.

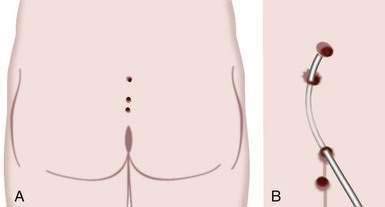

A seton is a rubber band-like material that is threaded through a fistula so that its two ends can be tied loosely external to the outside skin (Fig. 125-10).68 Setons may be used to drain a fistulous tract before surgical repair to prevent the accumulation of pus; however, they also can be therapeutic if used as a cutting seton. In this latter approach, after the seton is placed, the skin is incised over the fistulous tract, and the seton is tightened gradually over weeks to months until it gradually cuts through the muscle. This technique allows the fistulous tract to be unroofed gradually as the cut ends of the muscle scar close to their usual location, thereby lessening the chance of incontinence.

SPECIAL FISTULAS

Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease

Fistulas due to Crohn’s disease might not be cryptoglandular in origin but may be related to increased lymphoid tissue in the intersphincteric plane. They usually are complex, with curved, multiple tracts. Any unusual fistula or nonhealing fistulotomy site should raise the possibility of Crohn’s disease. Anal disease may be the first or the only manifestation of Crohn’s disease. Anorectal abscesses and suppuration may be less tender in patients with Crohn’s disease than in some patients with cryptoglandular fistulas.69

Treatment is tailored to the overall activity of the Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 111). The goal is to improve the patient’s quality of life; curing the Crohn’s disease is not realistic, and healing the fistula might not be possible. In patients with severe colonic or rectal Crohn’s disease, the placement of a loose seton in an anal fistula can decrease symptoms; the seton may be left in indefinitely.69 Some patients improve simply with the addition of oral metronidazole with or without ciprofloxacin.70 The immunomodulator 6-mercaptopurine also has been used with some success, A meta-analysis in which fistula closure was a secondary end point revealed healing in 54% of patients treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine compared with 21% who healed on placebo.71

In two randomized, controlled trials, infliximab was shown to be effective in healing perianal Crohn’s fistulas.72,73 In the first, closure of all fistulas for four weeks was seen in 38% of patients treated with infliximab at a dose of 5 mg/kg, in 55% of those treated with 10 mg/kg, and in 13% of patients receiving placebo.72 In another randomized, controlled trial of 296 patients, 87% of whom had perianal fistulas, complete closure of fistulas was seen at 54 weeks in 36% of patients treated with infliximab (5 mg/kg) compared with 19% of those treated with placebo. Of patients who lost response during maintenance treatment, 61% of patients who had been maintained on placebo responded to infliximab (5 mg/kg) and 57% of patients maintained on infliximab at 5 mg/kg responded to an increased dosage (10 mg/kg).73 In 10 uncontrolled series using cyclosporine, a rapid response was seen in 83% of patients, but a high relapse rate occurred when patients were switched from intravenous to oral therapy.74

Fistulotomy may be done for low fistulas with minimal anorectal involvement69; however, a nonhealing wound can persist after such therapy. Advancement flaps may be used successfully to close Crohn’s fistulas, as long as Crohn’s disease in the anorectum is only minimally active at the time of attempted repair. Despite the array of approaches, some patients have severe perianal sepsis and require fecal diversion with an ileostomy. In many, proctectomy is required later because of persistent discomfort or other problems. In general, surgical repair must be used with caution in anal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, and chronic, indwelling, loose setons are preferred to control symptoms of sepsis while preserving anal function.

Anovaginal Fistulas

In women with Crohn’s disease, anovaginal fistulas present additional challenges. Traditionally, proctectomy or long-term seton drainage have been the accepted methods of treatment. Most such fistulas are too short to be amenable to fibrin glue. Surgical treatment with various flap repairs, however, has been successful: In one study of 35 women, the initial success rate in selected women was 54%, with 68% healing after multiple flap procedures.75,76

Anovaginal fistulas not associated with Crohn’s are also difficult to treat. Almost all are related to obstetric injury, and a few are cryptoglandular in origin. The local tissue usually is scarred and too rigid for successful treatment with advancement flaps. The anovaginal septum is usually very thin. Repair of the sphincter in conjunction with repair of the fistula to give more tissue bulk to the anovaginal septum is the procedure of choice in this situation.77

Fistulas after Radiation Treatment

Fistulas associated with radiation treatment, usually for cervical or prostate cancer, also are challenging (see Chapter 39). The first issue is to exclude recurrent cancer as the cause of the fistula. If the output of stool and gas per vagina is great, a stoma may be needed. A stoma also allows the bypassed tissue to soften, so additional treatment options can be evaluated. It can take up to a year for the area to become pliable enough for a reasonable attempt at surgical intervention to be undertaken. Repair with a flap can be attempted if the tissue looks normal and is pliable, but this rarely is the case. Resection of the rectum with anastomosis of healthy colon to the anus at the dentate line can be successful (coloanal anastomosis). Interposition of the gracilis muscle between the wall of the anorectum and vagina or urethra brings healthy tissue to the area and can lead to healing.

ANAL MALIGNANCIES

Anal cancers are rare. They account for 1.5% of gastrointestinal cancers in the United States with 3500 new cases each year.78 The incidence has increased 2% to 3% every year in the United States since the early 1980s.79 Almost 80% are squamous cell cancers, 16% are adenocarcinomas, and 4% are other types.80 Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal behaves like adenocarcinoma of the rectum and is treated as such. Patients undergo abdominal-perineal resection with preoperative or postoperative chemoradiation therapy when the tumor is large, invades other organs, or has nodal involvement.

Tumors arising in the distal anal canal usually are keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas. Those arising in the transitional mucosa often are nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas. In the past, the two nonkeratinizing subtypes were referred to as transitional cell and cloacogenic. All anal carcinomas today are considered to be variants of squamous cell carcinoma, with various degrees of glandular and adnexal differentiation. The type previously called transitional cell carcinoma is composed of large cells, and the type previously referred to as cloacogenic carcinoma is composed of small cells,81 but microscopically, these tumors may be heterogeneous, and it is not useful to subclassify them. Keratinizing and nonkeratinizing squamous cell cancers exhibit similar behavior. Anal bleeding is the most common symptom (45%), followed by the sensation of a mass (30%); 20% of patients have no symptoms.81 The development of anal cancer has been associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) and HIV infections, history of receptive anal intercourse, history of sexually transmitted diseases, history of cervical cancer, and use of immunosuppressive medication after solid organ transplantation.82

ANAL CANAL CANCERS

In the past, standard treatment of anal canal cancers was abdominal-perineal resection with a permanent colostomy. In 1974, Nigro and colleagues presented the results of combined radiation and chemotherapy and showed that cure was possible without abdominal-perineal resection.83 This led to a regimen of external-beam radiation with fluorouracil and mitomycin as the treatment of choice; surgery was reserved for residual cancer seen in the scar after treatment. Cisplatin has been substituted for mitomycin in treatment trials, and complete response rates to combination treatment have been seen in 94% of patients. In one study, at a follow-up of 37 months, only 14% of patients required a colostomy for residual or recurrent disease.84 With a follow-up mean of 5.6 years, another study found 30% of patients needed a stoma for recurrent or persistent disease.85

Patients with persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal are treated with an abdominal-perineal resection. About 50% of such patients who undergo such surgery can be cured.81 Success also has been reported with an additional boost of radiation therapy combined with cisplatin-based chemotherapy.81

MELANOMA

Melanoma is as deadly in the anal region as elsewhere. Surgical excision offers the only chance for cure, and even this treatment has poor results. Because of the rare success with any treatment, many investigators have questioned the use of abdominal-perineal resection for anal melanoma instead of wide local excision. In one study, 2 of 19 (10%) patients survived, both of whom had wide local excision alone.86 The authors commented that anal ultrasound may be a valuable guide to treatment and recommended that if ultrasound shows that the lesion can be excised, wide excision should strongly be considered to avoid a permanent stoma, because most patients have regional or distant metastasis at presentation.86

ANAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is described as a dysplastic condition of the epithelium of the anal canal and perineal skin. There are several other commonly used terms for this condition, such as Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, or anal squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL). Anal intraepithelial neoplasia is the more commonly used term now. There seems to be a progression from low-grade (AIN I) to high-grade (AIN III) lesions, similar to that observed in the cervix. It appears that Bowen’s disease is AIN III. AIN may be discovered at the time of pathologic examination of anal tissue obtained for an unrelated surgery.87

Disagreement continues regarding treatment of high-grade AIN.87 One approach is by high-resolution anoscopy with directed therapy: 3% acetic acid is applied to the distal rectal mucosa, anal mucosa, and perianal skin to allow aceto-whitening. Examination is then done with an operating microscope, looking for patterns suggesting high-grade dysplasia such as punctation and mosaicism. Then the tissues are painted with 10% iodine (Lugol’s solution). Normal tissue will appear dark, and tissue that has high-grade intraepithelial changes appears mustard-yellow to tan. Directed destruction of tissue that has the characteristics of high-grade dysplasia is performed with electrocautery88; using this approach, no HIV-seronegative patient developed recurrent high-grade AIN; however, 79% of HIV-positive patients had recurrent or persistent lesions.

Another approach reasons that because the condition stems from HPV infection (anal warts; see later) as a predisposing factor,89 the virus will remain in the “normal” tissue that is not excised. Accordingly, the best treatment option for patients with AIN III (including HIV-positive patients) may be close observation, with regular biopsy of any suspicious areas to exclude invasive malignancy.90,91

ANAL WARTS

Anal warts, or condylomata acuminata, are caused by HPV. It is believed that most squamous cell cancers of the anal area also are caused by this virus. Condylomata affect 5.5 million Americans yearly, and the prevalence in the United States is about 20 million persons.92 Condylomata are caused by sexual transmission of HPV, although nonsexual transmission is possible.93 These lesions occur more commonly in men who have sex with men, in immunosuppressed patients, and in persons who have large numbers of sexual partners.87 Numerous treatment modalities exist (Table 125-3), but even when bulky lesions have resolved, the virus remains.

| TREATMENT | SUCCESS RATE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Podophyllin | 20-50% |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Podophyllin is a topical agent that is antimitotic. It requires repeated applications in the office.94 As a single agent, it results in cure rates of 50%.94,95 Podophyllin cannot be used in the anal canal, however, and is poorly absorbed by lesions that are keratinized, a characteristic of long-standing warts. The drug can cause skin irritation and is teratogenic in animals.

Trichloroacetic and dichloroacetic acid cause sloughing of tissue. These acids must be used with care to control the depth and size of the wound. They can be used in the anal canal. Cure rates of 75% have been reported with their use.94,96

Cryotherapy can be used in the anal canal. The depth and width of the wound must be monitored carefully. Success rates are similar to those associated with trichloroacetic acid.94,97

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) penetrates the skin and is used in a 5% cream. Success rates for 5-FU have ranged from 50% to 75%. Perhaps the best use of topical 5-FU is its biweekly application after surgical removal of warts to decrease rates of recurrence.98

Imiquimod cream is an immune response modifier that stimulates monocytes and macrophages to produce cytokines that affect cell growth and have an antiviral effect.99 The cream is applied to the warts at bedtime three times a week for a total of 16 weeks. Imiquimod cannot be used for anal canal warts. The drug seems to work better for women than for men, with one study reporting clearance of warts in 72% of women compared with 33% of men.100 Few side effects have been reported, although local skin irritation is common.

Surgical excision and cautery yields the highest success rate, with cure rates of 63% to 91%; laser seems to offer no advantage over cautery. Disadvantages of cautery include the need for local or other forms of anesthesia and the presence of bioactive HPV in cautery-induced fumes.94,101 Immune status seems to influence recurrence rates of condyloma. One study found significantly more recurrences in a shorter period for those with an immunocompromised status (defined as persons who are HIV-positive, or who have leukemia, idiopathic lymphopenic syndrome, a transplanted organ, or who are on chemotherapy).102

Interferon-α is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for injectional therapy of refractory condylomata acuminata. The dose is 106 units injected beneath a maximum of five lesions up to three times weekly for three to eight weeks. Recurrence rates are 20% to 40%.103 Topical interferon cream is ineffective.104 Surgery to eradicate the largest lesion, combined with topical or intralesional therapy, can decrease recurrence rates, and I have used it successfully when patients have a rapid recurrence of disease following surgical excision alone.

One promising therapy appears to be HspE7. This is a novel fusion protein that combines immune stimulatory properties with an appropriate target antigen from HPV. In one study, HspE7 was broadly active for multiple HPV types.105 The warts were found to improve substantially, but they usually did not disappear totally at the six-months follow-up. Patients were HIV-negative and received three subcutaneous injections of HspE7. More studies are under way to further evaluate these findings.

Anogenital warts can affect immunocompromised patients, including those who are HIV-positive and transplant recipients. In such persons, the warts are more aggressive, recur earlier, and are more often dysplastic than in immunocompetent persons. In HIV-positive patients, dysplasia and histologic evidence of HPV can occur in the absence of gross warts.106 Gross warts should be treated as discussed earlier. Topical 5-FU cream and serial examinations, rather than extensive excision, have been advocated for HIV-positive patients with dysplasia.106 Excision is reserved for patients with obvious lesions of the skin. Anal cytology (the “anal Pap test”) has been recommended for this group of patients, but as yet there are no uniform guidelines for its use.

Buschke-Löwenstein tumors are a rare variant of anal warts. These lesions appear as giant condylomata that grow rapidly, invade locally, and cause extensive destruction of surrounding tissue. Treatment is surgical excision, if possible. These lesions also have responded to radiation therapy.107

Table 122-4 outlines the treatment options for anal warts.

PRURITUS ANI

In a prospective study, 109 patients were referred over a period of two years to a colorectal clinic with a primary symptom of itching. On evaluation, 26 patients were found to have some form of colorectal or anal dysplasia, 56 had anorectal disease (most commonly fissures or hemorrhoids), and 27 had no identifiable etiologic disorder.108 After surgical treatment of all patients with colorectal neoplasia, their itching resolved. Of the 56 patients with anorectal disease, six continued to have itching after medical or surgical treatment. All 27 of the patients with no obvious cause for their itching underwent conservative medical treatment, and six continued to have persistent symptoms.7

A thorough history and physical examination are the starting points for evaluating patients with anal itching. Examination of the rectum and sigmoid colon should be included. The pattern of irritation should be noted, and consideration should be given to biopsy any abnormal skin. Usually, diet-induced pruritus is symmetrical, whereas infectious causes lead to an asymmetrical pattern of anal irritation. Leakage of stool due to fecal incontinence and leakage of mucus are common sources of pruritus ani and may be associated with prolapsing hemorrhoids or true rectal prolapse. Other causes include contact dermatitis, infections (e.g., candidiasis), parasites, systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus), diet (caffeine in coffee, cola, or chocolate; dairy; citrus; beer; and others), and some medications. It has been said that dietary factors, especially any form of caffeine, may be the most common culprit.109 The exact mechanism whereby caffeine might act as an irritant to the perianal skin is unclear.

Any underlying disorder should be treated; however, in many patients the cause of pruritus ani cannot be identified. These patients should be advised to modify their cleansing habits and to eliminate potential caffeine-related dietary culprits such as coffee, tea, and chocolate during a trial period. Most important is to convince the patient to stop “polishing” his or her anus. Frequently, the patient feels that the anal area is unclean, and he or she rubs the area vigorously, both for comfort and to try to clean the area more completely. Wiping gently with wet facial tissue or baby wipes is recommended. Avoiding soap and a washcloth in the shower may help. The patient should be instructed to use plain water and his or her hand to wash the perineum in the tub or shower. Creams or emulsifying ointments may be used instead of soap.110 Perfumed soaps and astringents (such as witch hazel) should be avoided. Tissue paper or a cotton ball placed by the anus and changed several times a day will absorb moisture and create a drier environment. A diet high in fiber with plenty of fluids (similar to the diet described for hemorrhoids) is recommended. A limited amount of 1% hydrocortisone cream can be used. Patients should be warned that chronic use of hydrocortisone will thin the anal skin and can lead to more problems.

Most patients respond to this regimen. Relapse is common and can require re-education of the patient. The physician should be aware that a previously overlooked underlying problem may be the cause of the pruritus and should take a fresh look at a patient who has a relapse. Assistance from a dermatologist also may be helpful and should be considered initially.110

Intradermal injection of methylene blue has been used successfully for the treatment of intractable idiopathic pruritus ani that has not responded to any other measures.111

ANAL STENOSIS

Anal stenosis is a narrowing of the anal canal. The condition can develop after anorectal surgery, usually radical hemorrhoidectomy. Surgeons in the modern era have modified their surgical technique in an attempt to prevent this problem. Other causes include chronic anal fissure, inflammatory bowel disease (especially Crohn’s disease), chronic diarrheal disease, infections (tuberculosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, syphilis, and others), cancer, and irradiation (see Chapter 39).112

Treatment of anal stenosis depends on the degree of stenosis and associated symptoms. In mild stenosis, the examiner’s finger can be placed just through the narrowing. Patients consume a high-fiber diet and bulking agents to produce stools that pass more easily, but patients must be cautioned to drink sufficient fluids so that they do not become constipated. Additionally, the bulky stools provide natural dilation. Gradual dilation by the patient (usually daily in the shower) with a commercial medical dilator or a smooth white candle also can produce improvement.113 The candle should be devoid of fragrance and coloring, both of which could potentially be irritating to the anal skin.

In moderate stenosis, more force is required to insert the index finger. Patients might respond to dietary changes and graded dilations. The initial dilation may need to be done under anesthesia. If improvement is insufficient, surgery is indicated. Release of a stricture or a sphincterotomy might suffice; however, some patients require an advancement flap.113

In severe stenosis, even the tip of the examiner’s fifth finger might not be able to be inserted into the anal canal. There is loss of the anoderm, and surgical intervention is needed to deliver healthy tissue into the anal canal to compensate for this loss. Various advancement flaps are successful, and the type used depends on the patient’s anatomy and the surgeon’s preference.113

UNEXPLAINED ANAL PAIN

COCCYGODYNIA

Coccygodynia is a pain or ache in the coccyx, commonly referred to as the tailbone, and typically results from trauma or arthritis. Movement of the coccyx on digital rectal examination can reproduce the pain. Treatment in the acute setting includes sitz baths, NSAIDs, and stool softeners.114 Glucocorticoid injections have been used in an attempt to reduce the pain. Rarely, removal of the coccyx is necessary.115

LEVATOR ANI SYNDROME AND PROCTALGIA FUGAX

Symptoms and Signs

Levator ani syndrome typically affects women younger than 45 years of age. Episodes of pain are chronic or recurring and, by definition, occur during 12 weeks in the preceding year, with each episode lasting 20 minutes or more.116 The discomfort is described as a vague tenderness or aching sensation high in the rectum. Discomfort usually does not awaken the patient from sleep and usually is worse after defecation and with sitting; walking or lying down seems to relieve the pain.117 Symptoms have been attributed to spasm of the levator muscles. Physical examination may be normal, or the levator muscle might feel like a tight, tender band on rectal examination.114

Proctalgia fugax occurs in young men and persons with perfectionistic-type personalities. It is seen in early adulthood and subsides by middle age. The pain lasts seconds or minutes and then disappears. Pain is described as a sharp cramp or stabbing and can awaken the patient from sleep.118,119 The pathogenesis is thought to involve anal smooth muscle dysfunction, perhaps triggered by stressful events.117 The frequency of proctalgia fugax may be increased in patients with other functional gastrointestinal complaints, such as unexplained abdominal pain, bloating, irritable bowel syndrome, and a sensation of incomplete evacuation after defecation. Physical examination is normal.114,116,117

Treatment

Treatment of the levator ani syndrome and proctalgia fugax is controversial, and no single treatment works for all patients. Treatments for these disorders are grouped together, in part because of our incomplete understanding of the two conditions. Initial treatment is reassurance, sitz baths, perineal strengthening exercises, regulation of bowel habits, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. These measures are usually effective.114 Many other treatments have been proposed, including electrogalvanic stimulation,118 levator massage, biofeedback,119 drug therapies, acupuncture, and psychiatric evaluation.

In the past, the drug treatment of choice was benzodiazepines; however, because of their addictive potential and the chronic nature of these problems, the popularity of these drugs has declined. In the only randomized, controlled trial for proctalgia fugax, a salbutamol inhaler was used successfully.120 Two puffs at the onset of pain were reported to lead to rapid relief.

Clonidine, an α2-adrenergic agonist, relaxes smooth muscle and has been used successfully.121 The dose is 150 mg twice daily for three days, tapered to 75 mg twice daily for two days, and then 75 mg daily for two days. Diltiazem, a calcium channel blocker, relaxes smooth muscle and also has been effective in a dose of 80 mg twice daily.122 Topical nitroglycerin, 0.2% or 0.3%, applied at the onset of proctalgia fugax also has been used successfully.123 I have had good results using amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, a side effect of which is muscle relaxation. The initial dose is 25 mg nightly and can be increased to 50mg after two weeks, if needed.

A newer treatment involves linearly polarized near-infrared irradiation therapy.124 One study used this treatment for patients with strongly tender points in each side of the rectum rather than in the anal canal. Of 35 patients, 33 had good or excellent improvement in pain after an average of 2.5 20-minute treatments.124

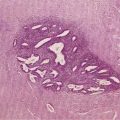

HIDRADENITIS SUPPURATIVA

Hidradenitis suppurativa is an inflammatory disease of the apocrine sweat glands and adjacent connective tissue. The initiating event is occlusion of an apocrine duct by a keratinous plug, leading to ductal dilatation and stasis, and then to secondary bacterial infection. The infection often ruptures into the surrounding soft tissue (Fig. 125-11). The chronic, cyclic nature of the disease ultimately leads to fibrosis and hypertrophic scarring of the skin. The axilla is the most common site of disease, followed by the anogenital region. Clinical features include recurrent abscesses, chronic draining sinuses, and indurated, scarred skin and subcutaneous tissues.124–128 The spectrum of severity ranges from mild disease with spontaneous regression to severe involvement at multiple sites. Coexistent Crohn’s disease occurs more commonly than expected, with an incidence of nearly 40% in one study.127

Diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa is based on the clinical presentation. A firm, pea-sized nodule may be detected and may rupture spontaneously. The lesion heals with fibrosis but can recur adjacent to the original area. Over time, multiple abscesses and sinus tracts develop in the subcutaneous region to form a honeycomb-like pattern.126 Discharge from the open areas may be serous or purulent.

Treatment consists initially of antibiotics active against Staphylococcus. Oral isotretinoin has been used successfully in mild cases.128 Intralesional glucocorticoids, antiandrogen therapy, and topical clindamycin129 also have been used. Surgery is required for chronic disease. Apparent cure can be achieved by extensive excision of the involved area down to the soft tissue and with wide margins. The area is then closed with a skin graft or left to granulate.130,131 New lesions can develop in untreated skin, and close follow-up is needed.

PILONIDAL DISEASE

Pilonidal disease is an acquired problem that generally affects young adults after puberty. It occurs in the intergluteal cleft and may be confused with fistula-in-ano. The prevailing theory of pathogenesis is that hair in the cleft, along with desquamated epithelium, is propelled into the base of the cleft, where the barbs of the hair shafts prevent them from being expelled, thereby setting up a granulomatous reaction, which creates a sinus.132 Free hair is found in the cyst or abscess cavity and also may be seen protruding from pits in the intergluteal cleft. The diagnosis is made by identifying the abscess, which characteristically is several centimeters cephalad to the anus, or tiny openings in the intergluteal cleft over the sacrum (Fig. 125-12).

In mild cases, successful treatment has been achieved simply by shaving the hair on a regular basis (usually monthly) to prevent the hair from embedding in the intergluteal cleft. Any abscess requires immediate drainage. In patients with chronic disease, more extensive surgical treatment is needed. Such surgery usually consists of unroofing all sinus tracts, with marsupialization; excision of the area, with or without closure of the skin edges; or creation of advancement flaps, musculocutaneous flaps, or some variant of these.132–136 When extensive surgical débridement is needed, vacuum-assisted closure devices have been shown to decrease length of time until the wound is healed.137 Afterward, it is still necessary to shave the surrounding hair periodically to prevent recurrence. As with any other chronic draining fistula or sinus, squamous cell carcinoma may arise with long-standing disease.138

RECTAL FOREIGN BODY

Most foreign bodies in the rectum are not the result of oral ingestion, but rather from placement into the rectum via the anus. Treatment (removal) often requires skill, trial and error, and luck to avoid a laparotomy. Most rectal foreign bodies result from sexual (erotic) stimulation or criminal assault. The history obtained from the patient is notoriously unreliable139 as to what exactly the object is and how it was placed. If the patient indicates that the object was placed as a result of sexual assault, a full sexual assault examination is needed, including perianal brushings and sampling for sperm.140 An abdominal film is useful to determine the size and location of the foreign body. If free air is seen, a laparotomy is almost unavoidable.

Imagination is needed at times to remove the object via the anus. Obstetric forceps and an obstetric vacuum extractor have been used with success.141 Another innovative approach is to put plaster of Paris into the foreign body (if it is a hollow object) and place a string into the plaster of Paris. The plaster then is allowed to harden, and the string is pulled out with the foreign body.139 Having the patient in the lithotomy position allows pressure to be applied simultaneously over the lower abdomen to facilitate expulsion of the foreign body.

After any foreign body has been removed from the anus, sigmoidoscopic examination is needed to rule out a perforation. If the sigmoidoscopic examination is negative, a water-soluble contrast enema study or CT scan with contrast should be done as well to exclude a perforation, even if the foreign body does not look capable of causing injury.142

Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, et al. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91:476-80. (Ref 68.)

Champagne BJ, O’Connor LM, Furguson M, et al. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1817-21. (Ref 61.)

Chang GJ, Berry JM, Jay N, et al. Surgical treatment of high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions: A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:453-8. (Ref 88.)

Christoforidis D, Etzioni D, Goldberg SM, et al. Treatment of complex anal fistulas with the collagen fistula plug. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1482-7. (Ref 63.)

Hull TL, Fazio VW. Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173:95-8. (Ref 75.)

Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PHD, Malthaner RA. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy is associated with a higher long-term recurrence rate of internal hemorrhoids compared with conventional excisional hemorrhoid surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1297-1305. (Ref 33.)

Jorge JMN, Wexner SD. Anatomy and physiology of the rectum and anus. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:723-31. (Ref 3.)

Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgical anatomy. In: Keighley MRB, Williams NS, editors. Surgery of the anus, rectum and colon. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:7. (Ref 1.)

MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatment modalities: A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:687-94. (Ref 18.)

McGuinness JG, Winter DC, O’Connell PR. Vacuum-assisted closure of a complex pilonidal sinus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:274. (Ref 137.)

Nelson R. A systematic review of medical therapy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:422-31. (Ref 39.)

Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine BJr. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: A preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:354-56. (Ref 83.)

Sajid MS, Hunte S, Hippolyte S, et al. Comparison of surgical vs chemical sphincterotomy using botulinum toxin for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: A meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:547-52. (Ref 47.)

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-85. (Ref 73.)

Senagore A, Singer M, Abcarian H. A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter trial comparing stapled hemorrhoidopexy and ferguson hemorrhoidectomy: One-year results. Podium presentation at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons meeting, Chicago, June 3-8, 2002. (Ref 29.)

1. Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgical anatomy. In: Keighley MRB, Williams NS, editors. Surgery of the anus, rectum and colon. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:7.

2. Godlewski G, Prudhomme M. Embryology and anatomy of the anorectum. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:319.

3. Jorge JMN, Wexner SD. Anatomy and physiology of the rectum and anus. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:723.

4. Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJA, Boerma MO. Anal fissure: New concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(Suppl 218):78.

5. American Gastroenterological Association. Medical position statement on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:732.

6. Ringel Y, Dalton CB, Brandt LJ, et al. Flexible sigmoidoscopy: The patient’s perception. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:315.

7. DiSario JA, Sanowski RA. Sigmoidoscopy training for nurses and resident physicians. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:29.

8. Soussan EB, Mathieu N, Roque I, et al. Bowel explosion with colonic perforation during argon plasma coagulation for hemorrhagic radiation-induced proctitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:412.

9. Orkin B, Young H. When are “hemorrhoids” really hemorrhoids? A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:A35.

10. Cirocco WC. A matter of semantics: Hemorrhoids are a normal part of human anatomy and differ from hemorrhoidal disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:772.

11. Mazier WP. Hemorrhoids, fissures, and pruritus ani. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1277.

12. Nelson RL, Abcarian H, Davis FG, et al. Prevalence of benign anorectal disease in a randomly selected population. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:341.

13. Metcalf A. Anorectal disorders. Postgrad Med. 1995;98:81.

14. Pfenninger JL, Surrell J. Nonsurgical treatment options for internal hemorrhoids. Am Family Phys. 1995;52:821.

15. Orkin BA, Schwartz AM, Orkin M. Hemorrhoids: What the dermatologist should know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:449.

16. Kaman L, Aggarwal S, Kumar R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis after injection sclerotherapy for hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:419.

17. Barwell J, Watkins RM, Lloyd-Davies E, Wilkins DC. Life-threatening retroperitoneal sepsis after hemorrhoid injection sclerotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:421.

18. MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatment modalities: A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:687.

19. Scaglia M, Delaini GG, Destefano I, Hulten L. Injection treatment of hemorrhoids in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:401.

20. Chew SSB, Marshall L, Kalish L, et al. Short-term and long-term results of combined sclerotherapy and rubber band ligation of hemorrhoids and mucosal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1232.

21. Armstrong DN. Multiple hemorrhoidal ligation: A prospective, randomized trial evaluating a new technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:179.

22. Smith LE, Goodreau JJ, Fouty WJ. Operative hemorrhoidectomy versus cryodestruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:10.

23. Linares Santiago E, Gomex Parra M, Mendoza Olivares FJ, et al. Effectiveness of hemorrhoidal treatment by rubber band ligation and infrared photocoagulation. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:238.

24. Loder PB, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RKS. Haemorrhoids: Pathology, pathophysiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1994;81:946.

25. Konsten J, Baeten CGMI. Hemorrhoidectomy vs. Lord’s method: 17-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:503.

26. Arbman G, Krook H, Haapaniemi S. Closed vs. open hemorrhoidectomy: Is there any difference? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:31.

27. Nicholson TJ, Armstrong D. Topical metronidazole (10 per-cent) decreases posthemorrhoidectomy pain and improves healing. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:711.

28. Longo A. Treatment of hemorrhoid disease by reduction of mucosa and hemorrhoid prolapse with circular-suturing device: A new procedure. Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery. Rome, June 3-6, 1998, p 777.

29. Senagore A, Singer M, Abcarian H. A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter trial comparing stapled hemorrhoidopexy and ferguson hemorrhoidectomy: One-year results. Podium presentation at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons meeting, Chicago, June 3-8, 2002.

30. Peng BC, Jayne DG, Ho Y-H. Randomized trial of rubber band ligation vs. stapled hemorrhoidectomy for prolapsed piles. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:291.

31. Carriero A, Longo A. Intraoperative, perioperative and postoperative complications of stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Osp Ital Chir. 2003;9:333.

32. Maw A, Eu K-W, Seow-Choen F. Retroperitoneal sepsis complicating stapled hemorrhoidectomy: Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:826.

33. Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PHD, Malthaner RA. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy is associated with a higher long-term recurrence rate of internal hemorrhoids compared with conventional excisional hemorrhoid surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1297.

34. Fueglistaler P, Guenin MO, Montali I, et al. long-term results after stapled hemorrhoidopexy: High patient satisfaction despite frequent postoperative symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:204.

35. Jongen J, Bach S, Stubinger SH, Bock J-U. Excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoid under local anesthesia: A retrospective evaluation of 340 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1226.

36. Perrotti P, Antropoli C, Molino D, et al. Conservative treatment of acute thrombosed external hemorrhoids with topical nifedipine. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:405.

37. Moore B, Fleshner P. Rubber band ligation for hemorrhoidal disease can be safely performed in select HIV-positive patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:A32.

38. Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJA, De Graaf EJR. Ischaemic nature of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996;83:63.

39. Nelson R. A systematic review of medical therapy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:422.

40. Richard CS, Gregoire R, Plewes EA, et al. Internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin in the treatment of chronic anal fissure: Results of a randomized, controlled trial by the Canadian Colorectal Surgical Trials Group. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1048.

41. Jonas M, Speake W, Scholefield JH. Diltiazem heals glyceryl trinitrate–resistant chronic anal fissures: A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1091.

42. Jost W, Schimrigk K. Use of botulinum toxin in anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:974.

43. Maria G, Cassetta E, Gui D, et al. A comparison of botulinum toxin and saline for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:217.

44. Brisinda G, Maria G, Bentivoglio AR, et al. A comparison of injections of botulinum toxin and topical nitroglycerin ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:65.

45. Mentes BB, Irkorucu O, Akin M, et al. Comparison of botulinum toxin injection and lateral internal sphincterotomy for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:232.

46. Minguez M, Herreros B, Espi A, et al. Long-term follow-up (42 months) of chronic anal fissure after healing with botulinum toxin. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:112.

47. Sajid MS, Hunte S, Hippolyte S, et al. Comparison of surgical vs chemical sphincterotomy using botulinum toxin for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: A meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:547.

48. Sajid MS, Rimple J, Cheek E, Baig MK. The efficacy of diltiazem and glyceryltrinitrate for the medical management of chronic anal fissure: A meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1.

49. Argov S, Levandovsky O. Open lateral sphincterotomy is still the best treatment for chronic anal fissure. Am J Surg. 2000;179:201.

50. Evans J, Luck A, Hewett P. Glyceryl trinitrate vs. lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: Prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:93.

51. Parellada C. Randomized, prospective trial comparing 0.2 percent isosorbide dinitrate ointment with sphincterotomy in treatment of chronic anal fissure: A two-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:437.

52. Corby H, Donnelly VS, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR. Anal canal pressures are low in women with postpartum anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1997;84:86.

53. Nyam DCNK, Wilson RG, Stewart AJ, et al. Island advancement flaps in the management of anal fissures. Br J Surg. 1995;82:326.

54. Janicke DM, Pundt MR. Anorectal disorders. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:757.

55. Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, et al. Endorectal advancement flap: Are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1616.

56. Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, Fazio VW. Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1622.

57. Schouten WR, Zimmerman DDE, Briel JW. Transanal advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1419.

58. Loungnarath R, Dietz DW, Mutch MG, et al. Fibrin glue treatment of complex anal fistulas has low success rate. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:432.

59. Sentovich SM. Fibrin glue for all anal fistulas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:158.

60. Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys MM, Cunningham C, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1608.

61. Champagne BJ, O’Connor LM, Furguson M, et al. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: Long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1817.

62. van Koperen PJ, D’Hoore A, Wolthuis AM, et al. Anal fistula plug for closure of difficult anorectal fistula: A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2168.

63. Christoforidis D, Etzioni D, Goldberg SM, et al. Treatment of complex anal fistulas with the collagen fistula plug. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1482.

64. Ky AJ, Sylla P, Steinhagen R, et al. Collagen fistula plug for the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:834.

65. Lawes Da, Efron JE, Abbas M. Early experience with the bioabsorbable anal fistula plug. World J Surg. 2008;32:1157.

66. Schwandner O, Stadler F, Dietl O, et al. Initial experience on efficacy in closure of cryptoglandular and Crohn’s transsphincteric fistulas by the use of the anal fistula plug. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:319.

67. Athanasiadis S, Helmes C, Yazigi R, Kohler A. The direct closure of the internal fistula opening without advancement flap for transsphincteric fistulas-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1174.

68. Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, et al. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91:476.

69. Sangwan YP, Schoetz DJJr, Murray JJ, et al. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:529.

70. Solomon MJ, McLeod RS, O’Connor BI, et al. Combination ciprofloxacin and metronidazole in severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1993;7:571.

71. Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Int Med. 1995;123:132.

72. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398.

73. Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876.

74. Sandborn WJ, Fazio W, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508.

75. Hull TL, Fazio VW. Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173:95.

76. Hull TL, Fazio VW. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. In: Phillips RKS, Lunniss PJ, editors. Anal fistula: Surgical evaluation and management. London: Chapman & Hall; 1996:143.