CHAPTER 16 Discography

In 1948, Lindblom1 originally reported discography as a method to identify herniated discs in the lumbar spine by injecting contrast medium into the disc and following the outline of contrast medium into the spinal canal. It was noted as only a secondary consideration of the test that reproduction of the patient’s usual sciatica sometimes occurred during the disc injection. It was observed later that back pain was sometimes reproduced during the injection, as opposed to sciatica. Eventually some clinicians began using the test to evaluate discs as the source of axial pain in patients without radicular symptoms.

Since the early use of discography, it has been unclear whether reproduction of pain with injection indicated that the injected disc is the true primary source of clinical back pain, or whether the injection had simulated the usual pain in an artificial manner. Over time, attempts have been made to determine the specificity of the test and to refine the technique to reduce the risk of false-positive or false-negative results. Still this test remains highly controversial. Even the staunchest proponents of the procedure state that “discography is a test that is easily abused.”2 Basic diagnostic test assessment has found fundamental problems with test reliability (i.e., does the test give the same result on repeated testing?) and validity (i.e., does the test prove what it purports to prove?). Also, it has not been shown that using the test improves the outcomes in patients receiving the test compared with patients not receiving the test. More recently, the long-term safety of disc puncture and injection has also been questioned. This chapter discusses the rationale and technique of provocative discography when used in patients with primary axial pain syndromes.

Clinical Context

Back and neck pain are very common, and in most cases determining the “cause” of a specific episode of back or neck pain is unimportant because these symptoms frequently resolve in a short time or do not seriously interfere with function.1 Provocative discography may be described as representing a tertiary diagnostic evaluation, which should be considered only in a select group of patients.

Discography Technique

Criteria for Positive Test

In an effort to improve the specificity of discography in diagnosing so-called discogenic pain, some investigators have used additional criteria beyond pain reproduction on injection. The criteria for establishing a positive discogram are controversial. The primary criteria for a “positive” disc injection are pain of “significant” intensity on disc injections (usually defined as ≥6 out of 10 pain scale) and a reported similarity of that pain to the patient’s usual, clinical discomfort (concordant pain). These basic criteria were proposed in the experimental work by Walsh and colleagues in 1990,29 which proposed “significant pain” be defined as 3 out of 5 (or 6 out of 10) on an arbitrary pain thermometer. “Bad pain” was defined as 3 out of 5 pain, and “moderate pain” was described as 2 out of 5 pain. The authors did not stringently define concordance of pain reproduction. Some investigators have proposed additional and sometimes idiosyncratic criteria for positive injections (Table 16–1).

TABLE 16–1 Suggested Criteria for Positive Provocative Discographic Injection

| Test Criteria for Positive Result | Positive Test Threshold | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Pain response (intensity) | ≥6/10 or 3/5 | Subjective and arbitrary scale. No data on reliability. Data on validity in small groups of asymptomatic subjects without psychosocial comorbidity are good (specificity >90%). Data in several studies of subjects with increased psychosocial or chronic pain comorbidity indicate validity in these subgroups is poor (specificity 20%-60%) |

| “Bad” pain or worse on pain thermometer | ||

| ≥7/10 | ||

| Qualitative pain assessment (concordant pain) | “Concordant pain” usually including “similar” but not exact pain | Subjective response. Data on reliability are unknown. Data on validity in small study of experimental nondiscogenic low back pain indicate validity is questionable |

| “Exact” pain only | ||

| Annular disruption | Dye must show fissure to or through outer anulus | Tested only in clinical studies without follow-up to confirm outcome or other “gold standard.” Radiologic reliability best with computed tomography scan after disc injection compared with x-ray alone. Validity of additional criteria as confirming true-positive test unknown; positive injection in discs without annular disruption more common in psychologically disturbed subjects |

| Control disc injections | “Negative” injection (minimal or discordant pain) required adjacent to proposed “positive” disc | Injections in morphologically normal discs seem to be reliably negative even in subjects with serious psychological distress and no back pain. Reliability in other disc morphology unknown. Validity of this additional criterion as confirming true-positive test unknown |

| “Normal” injection (i.e., no pain) | ||

| Some authors insist that adjacent “control disc” must also have grade 3 annular fissure, which is “relatively painless” at equal or higher pressures than “positive disc” | ||

| Demonstration of pain behavior | Facial expressions of pain must be observed to confirm verbal pain report | Reliability and validity of this criterion as confirming true-positive test unknown |

| Pressure-controlled injection | Disc injections should be classified into low (<15 psi or <20 psi) or high (>50 psi) pressures at time of significant pain response; responses at pressures in between are indeterminate | Small outcomes series suggest low pressure sensitive discs are better treated with interbody fusion techniques. Reliability and validity unknown |

| Volume-controlled injections | “Excessive volume” or speed to injection invalidated injection | Unvalidated concept based on anecdotal evidence. Primary data unavailable to analyze |

| Maximum one or two positive disc injections | More than one or two positive disc injections invalidates study (all are indeterminate) | Assumption is made that generalized hyperalgesic effect may lead to multiple positive discs around single pain generator |

| Quantify pain tolerance by response to buffered anesthetic injection | Subjects with poor pain tolerance may not be “ideal” candidates for discography; this feature needs to be detected | It is unclear that pain tolerance to intradermal anesthetic injection is valid test to determine “pain tolerance” in patients with long-standing axial pain |

| Needles should be inserted from asymptomatic or least symptomatic side | Theoretically this may decrease confusion between injection and insertion pain | Some data suggest this is not an important technique. No “gold standard” confirmation was applied |

| Any positive disc injection must be repeated with similar outcomes before accepting result as “positive” | Intraprocedure reliability test | No data available on whether this improved or decreased test accuracy |

Pain Generator Concept and Provocative Discography

When only degenerative changes are found, it is controversial whether or not a discrete local pain generator as the cause of serious back pain illness can be commonly identified. Some clinicians believe that serious axial pain and disability can be so multifactorial (mechanical, psychological, social, and neurophysiologic contributors) that it is unreasonable to expect specific diagnostic studies to confirm an anatomic “diagnosis” for axial pain illness in every patient.3–5 Even if a pain generator is suspected, it is unclear how this can be reliably confirmed to be the cause of the patient’s perceived pain, impairment, and disability in the face of complex social, emotional, and neurophysiologic confounders.

Other clinicians believe that identifying a pain generator is central to spine evaluations, is an expectation of patients, and determines the choice of treatments by focusing on the anatomic structure deemed responsible for the pain. In this model, social issues such as disability, litigation, psychological distress, and pain intolerance are believed to be secondary issues to the structural pathology.1,6–12 These clinicians generally believe that although the history and physical examination may be helpful in suggesting serious underlying pathology such as infection and tumor, these methods are not helpful in determining the true pain generator among many degenerative structures.

Diagnostic Injections and Modulation of Pain Perception in Axial Pain Syndromes

Many common factors are known to have potential dampening or amplifying effects on the perception of back and neck pain. These factors must be considered when evaluating the validity of diagnoses determined by diagnostic injections.13–18

Adjacent Tissue Injury

Injury to adjacent tissues may increase the perception of pain in surrounding structures by a local hyperalgesic effect. This is a well-known phenomenon that occurs with any tissue damage; it may amplify pain perception by increasing local inflammatory processes with secondary neurologic sensitization in areas not directly injured, such as the area surrounding a burn or a fracture that is sensitive but without any thermal or mechanical injury. This is an important phenomenon in patients with low back pain with serious disease at one or more levels, which may sensitize the adjacent segments to provocative testing (e.g., a spine that has undergone multiple operations).13,19

Local Anesthetic

Local anesthetic injections may decrease the perception of pain at a local site. This is the specific, active effect used in diagnostic blocks. This decrease in pain perception can also be a source of confounding effects if the exact placement of the agent is not well controlled. In addition to this direct local effect, a nonspecific placebo effect and a neurophysiologic modulation effect may occur. A relevant example is the effect of local anesthetic blockade on the perception of painful stimulus along the neuraxis proximal to the injection. A local anesthetic injection in the lower extremity may be perceived as relieving sciatica owing to disc herniation.20 This is not a placebo effect (i.e., the phenomenon is seen only with an active anesthetic agent) but rather an effect on neuromodulation. This effect is important in diagnostic anesthetic blockade as a source of false-positive and false-negative findings.21

Tissue Injury and Nociception in Adjacent or Same Sclerotome

Tissue injury having the same or adjacent sclerotomal afferents as lower spinal elements may increase pain sensitivity at any given site. This effect is thought to be due to physiologic and anatomic changes at the level of the dorsal root ganglion or spinal cord ascending tracts. In animal models, single afferent neurons from a dorsal root ganglion may innervate three adjacent discs and a wide range of adjacent structures. This effect is important in considering the specificity of discography at sites of similar embryonic derivation to a known pathologic structure (e.g., nonunion, spondylolisthesis, painful iliac crest bone graft site). The confounding effect of this phenomenon in discography has been experimentally and empirically shown (see later).13,22

Chronic Pain Syndromes

Chronic pain syndromes may complicate the evaluation of low back pain syndromes. Chronic pain from regional sites near the lumbar spine (chronic pelvic pain, irritable bowel syndrome, failed hip arthroplasty) or distant to the lumbar spine (chronic neck pain, chronic headache, temporomandibular joint syndrome) may increase pain sensitivity at lower spinal elements. This effect may be regional or global and may be related to neurophysiologic changes at multiple levels along the neuraxis. Preexisting chronic pain syndromes are also associated with depression, narcotic use, and habituation, which have independent pain perception effects. This effect has been shown to have an impact on the intensity of pain intensity from discography in experimental subjects.13,22

Narcotic Analgesia

Narcotic medications act at multiple levels to decrease pain sensitivity thresholds, intensity, and affective response. Administration of a narcotic medication may act as a common confounder of diagnostic techniques of any type requiring accurate feedback of pain perception from a patient.13,23,24

Depression, Anxiety, and Somatic Distress

Clinical depression, anxiety disorders, and increased somatic awareness may be seen as predisposing factors to chronic low back pain syndromes or reactions to the pain and disability of chronic low back pain illness or both. In either event, psychological distress usually decreases the pain threshold perception and increases perceived pain intensity and affective response.5,23,25 These effects are likely due to central neurochemical changes and systemic effects and have been shown to affect pain responses in discographic evaluation.

Summary

When considering the diagnostic certainty of a possible pain generator in chronic axial pain illness, it is necessary to view the aforementioned confounding factors for contribution to the illness behavior observed (Table 16–2). An injured soldier with facial trauma, after narcotic administration and in the heat of combat, may mask the perception of a significant low back pain injury, which otherwise could be clearly symptomatic. In this case, a bona fide local pain generator results in little pain perception. Conversely, a very minor nociceptive input (common backache) from a disc can be amplified in the case of a patient with multiple chronic pain syndromes, narcotic habituation, depression, and compensation issues (social disincentives). In this case, a common mild backache pain generator is amplified to become a catastrophic illness.

TABLE 16–2 Neurophysiologic Factors Influencing Result of Diagnostic Injections

| Modulator of Diagnostic Injection Effect | Type of Effect on Pain Perception at Site of Injection | Diagnostic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Adjacent tissue injury | Increased regional pain perception | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Local anesthetic | Decreased pain perception at depot site and sometimes in sclerotomal or referral pattern | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Tissue injury in adjacent or same sclerotome | Increased regional pain perception | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Chronic pain syndrome | Increased generalized pain perception | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Narcotic analgesia | Decreased generalized pain perception and affective response | Decreased sensitivity and increased specificity of provocative injections |

| Narcotic habituation | Increased pain perception and exaggerated affective response | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Depression, anxiety, and somatic distress | Decreased generalized pain perception and unpredictable affective response | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

| Social imperatives | Decreased pain perception, suppressed affective response | Decreased sensitivity and increased specificity of provocative injections |

| Social disincentives | Specific increased pain reporting and demonstration of pain behavior | Decreased specificity in provocative injection |

Evidence for Validity and Usefulness of Provocative Discography

The criteria for an evidence-based evaluation of the validity of diagnostic tests have been described by Sackett and Haynes.26 Four phases of scientific scrutiny and evidence in discography research are shown in Table 16–3. These phases of evidence progress from the simple comparison of testing in subjects known to have a disease with subjects who are completely normal without any signs, symptoms, or morbidity associated with the disease (phase I) to the blinded study of a diagnostic test in determining outcomes in actual clinical therapeutic intervention (phase IV).

TABLE 16–3 Four Phases of Evidence-Based Criteria for Evaluation Diagnostic Tests

| Phase of Study | Strategy | Discography Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Diagnostic test compared in subjects with index disease vs. results in complete normals (experimental setting) | Few painful disc injections in completely normal asymptomatic subjects (e.g., normal psychometric testing, normal disc morphology, no chronic pain issues, no compensation issues) |

| Phase 1 study examples: Walsh et al, 199029; Carragee et al, 200015 | ||

| Phase 2 | Evaluation of range of test results in subjects with disease (establishes positive result guidelines) compared with known normals | Wide range of pain reactions to injections in asymptomatic subjects depending on psychological status, disc morphology, chronic pain issues, compensation issues. Wide overlap between asymptomatic subjects and patients with presumed discogenic pain. |

| Phase 2 study examples: Carragee et al, 200015; O’Neill and Kurgansky, 200422; Carragee et al, 200638 | ||

| Phase 3 | Diagnostic test applied in clinical subjects likely to have disease (clinical setting of test application in subjects with similar presentation signs, symptoms, and risk factors) | Poor validity testing subjects with persistent low back pain with known nondiscogenic pain syndromes (e.g., iliac crest pain) or asymptomatic disc pathology (i.e., previous disc surgery). PPV approximately 50% in ideal patient, PPV  50% in typical discography patient (outcome findings) 50% in typical discography patient (outcome findings) |

| Phase 3 study examples: Carragee et al, 199914; Carragee et al, 200035; Derby et al, 200536; Carragee et al, 200237; Carragee et al, 200643 | ||

| Phase 4 | Does having the diagnostic test result improve outcomes compared with management without test result (controlled trial) | Little to no evidence of provocative discography improving outcomes compared with modern diagnostic techniques.40 Substantial evidence provocative discography is worse than anesthetic injection alone.42 Substantial evidence discography may worsen outcomes in certain at-risk groups44–46 |

PPV, positive predictive value.

After Sackett D, Haynes R: Evidence base of clinical diagnosis: The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ 324:539-541, 2002.

An example of a phase I diagnostic study is the classic study of discography by Walsh and colleagues29 in asymptomatic healthy young men without significant degenerative disease or comorbidities associated with chronic low back pain illness (e.g., depression, chronic pain behavior, compensation issues). Discography seemed to perform well in this phase I study, with little pain provocation in the subjects known to have no evidence of disease (1 of 10 subjects [10%, 95% confidence interval 0, 40%] had pain intensity rated “bad”). Phase II and III studies, comparing subjects without low back pain illness but with significant comorbidities, were more problematical, however.14,15

Generally, there has been limited high-quality evidence supporting provocative disc injections. Despite the limited evidence, some authors believe that primary discogenic pain is the most common cause of chronic low back pain illness.11,12,27,28 As is shown subsequently, a major constraint in this research has been a failure to use a bona fide “gold standard” for primary discogenic pain causing low back pain illness against which investigators document that the diagnosis suggested by discography is correct.

Validity of Discography

Specificity of Positive Discography: Testing on Subjects with No Axial Pain History

Careful technique and the standardization of discography were believed by many discographers to have reduced the false-positive rate to a negligible level in experienced hands. In 1990, Walsh and colleagues29 performed a carefully controlled set of discographic lumbar injections in 10 paid volunteers, all asymptomatic young men (mean age 22) with little disc degeneration. Of 30 discs injected in this asymptomatic group, 5 produced “minimum” pain (16.7%), 2 produced “moderate” pain (6.7%), and 1 produced “bad” pain (3.3%). Based on these data, the authors believed the risk of false-positive injections was very low. This study is frequently, and incorrectly, cited to confirm a 0% false-positive rate.

In 1997, a review of one discography practice25 found cases that seemed to be clinically apparent false-positive cases. These injections were believed to meet full criteria for discogenic pain, with concordant, painful injections and negative control injections. Clinical follow-up revealed other causes of the patients’ back pain illness, however, including spinal tumor, sacroiliac joint disease, and emotional problems. Block and colleagues30 related abnormal Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) testing and Ohnmeiss and colleagues31 related abnormal pain drawings with “nonorganic” features, suggesting possible false-positive discographic injections. Other authors performed thoracic32 and cervical33 injections in subjects asymptomatic for pain in those areas. Significantly painful injections were found to occur in approximately 30% of these volunteers.

Following the Walsh protocol, Carragee and colleagues15 examined 30 volunteer subjects with no history of low back pain who were recruited to undergo a physical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), psychometric testing, and provocative discography. The results showed that little pain was elicited by injection of any anatomically normal disc. Discs with advanced degenerative annular fissuring with dye leakage to the outer (innervated) annular margins were more commonly painful after discography than less degenerative or normal discs. The intensity of the pain reported by the subjects with annular disruption was predicted by the presence of chronic nonlumbar pain and abnormal psychological scores. Only 10% of subjects without any other pain processes had a positive disc injection by the Walsh criteria, but 50% of subjects with nonback chronic pain had at least one positive disc injection.

The interaction between pending compensation claim and discographic pain was also significant in this select group of volunteers. Of the 10 subjects with positive injections, 8 had had contested workers’ compensation or personal injury claims with resulting litigation. Conversely, of 9 subjects with disputed litigation claims, 8 had positive injections (P < .0001).15 It was not found, however, that all subjects involved in previous work injury claims had similar rates of positive disc injection. A history of an uncontested claim from a past compensation injury and no pending legal action did not predict significant pain on disc injection. Given that no subject in this study stood to have any secondary gain from positive discography, the increased pain reporting in subjects with unrelated but contested compensation claims is intriguing. It is possible that the effect of the prolonged social turmoil associated with a litigation dispute has the effect of diminishing one’s resilience to irritative stimuli. Another explanation could be that persons with abnormally low pain tolerance are more likely to have a legal dispute regarding the significance and damages associated with previous minor injury.

Discographic Injections in Previously Operated Discs

Provocative discography is frequently used to evaluate persistent or recurrent low back pain syndromes in patients who had undergone posterior discectomy. The validity of interpreting painful injections after herniation is unknown despite its common usage. Heggeness and colleagues34 reported on 83 postdiscectomy patients and found that 72% had a positive concordant pain response on injection of the previously operated disc. This study did not address the possibility of false-positive injections. All positive injections were assumed to be true-positive injections for identifying the source of the patient’s pain.

Using the same methodology developed by Walsh and colleagues,29 a large study of discography in asymptomatic patients after discectomy for sciatica was performed.35 Painful disc injections were frequently seen in the asymptomatic postdiscectomy group. As in previous studies, a higher rate of painful injections was seen in patients with abnormal psychological profiles.

Validity of Concordance Report

It is unclear to what extent similar neurologic and behavioral factors may influence the results in provocative discography. It is possible that the disc stimulation in discography may also provoke a “concordant” pain response without actually having located a true pain source. As discussed earlier, there have been reported cases of individuals undergoing discography who were diagnosed as having discogenic pain as the source of their illness on the basis of positive concordant disc injections, but who were subsequently shown to have nonspinal sources for their pain.25

This issue was investigated using an experimental model to determine the response to disc injection in patients known to have nonspinal back pain.14 Subjects with no history of back pain were recruited who were scheduled to undergo posterior iliac crest bone graft harvesting for nonspinal problems, mainly fracture nonunions or bone tumors. Most of these patients experienced low back and buttock pain from the bone grafting for several months postoperatively, and this pain was in a similar distribution to what is normally considered discogenic lumbar pain. Discography was performed several months after the bone graft harvesting, and subjects were asked to compare the quality and location of disc injection pain with their usual iliac crest pain.

Eight volunteer subjects were studied using the same protocol as the Walsh and colleagues study.29 All subjects had some disc degeneration on MRI, and 24 of the discs were injected. Of the 14 disc injections causing some pain response, 5 were believed to be “different” (nonconcordant) pains (35.7%), 7 were “similar” (50%), and 2 were “exact” pain reproductions (14.3%). The presence of annular disruption was correlated with concordant pain reproduction (P < .05). Of 10 discs with annular tears, injection of 7 elicited “similar” or “exact” pain reproduction to the pain at iliac crest bone graft harvest sites. By the strict criteria for positive discography, four of the eight patients (50%) had positive injections: The pain on a single disc injection was “bad” or “very bad,” and the pain quality was noted to be exact or similar to the usual discomfort. All subjects had a negative control disc. All positive disc injections had annular fissures. Half of the positive disc injections occurred at low pressures (<20 psi).14

Discography in Subjects with Minimal Low Back Symptoms

The ability of a test such as discography to discriminate a true pain generator disc responsible for causing serious disabling low back pain illness from another disc that causes only trivial or clinically inconsequential backache is critical to the test’s validity in clinical practice. Derby and colleagues36 performed discography in a group of 16 subjects with occasional or minimal low back pain, none of whom required current medical care or were experiencing disability because of low back pain. Of the 16 subjects, 5 (31%) had a pain response at 5 out of 10 or greater, and 2 (12.5%) had a pain response at 6 out of 10 or greater. The subjects with more frequent benign low back pain had more painful injections. None of these subjects had abnormal psychological profiles, compensation issues, or chronic pain syndromes or had significant secondary gain motivation to underreport pain. This study was confounded by potentially significant methodologic issues making the results open to criticism. These issues include using the investigators’ employees and staff as the subjects of the study.

In another study, the Stanford group performed experimental discography on 25 volunteer subjects with no clinical back pain illness; these volunteers had persistent low backache unassociated with any physical restrictions that was not bad enough to seek medical care.37 All subjects had normal psychological profiles, but half had other chronic pain syndromes that are risk factors for positive injections. In 36% of these subjects with common backache, discographic injection of one or more discs was significantly painful and concordant. All positive discs had annular disruption, and all had negative control discs. By the usual proposed criteria, these were positive disc injections for clinically significant discogenic pain illness. Discs sensitive to low pressure injections were found in 28% of subjects.

Pressure-Sensitive Injections and Discography Validity

In some cases, dye injected at low pressures may cause significant pain. Derby and colleagues8 labeled these “chemically” sensitive discs, as opposed to discs that are painful only on injection with high pressures. These authors theorized that “chemically” sensitive discs are painful because of the exposure of annular nerve endings or nearby neural structures to the leakage of some irritating substances. It is postulated that this pain is incited by chemical leakage from the disc during daily activities. This leakage is thought to be simulated by the disc injections. Low-pressure–positive discs are arbitrarily defined as discs found to be painful at pressures less than 15 psi or 22 psi greater than opening pressures.8,22 Derby and colleagues8 postulated further that disc injections eliciting pain at higher pressures (>50 psi), called “mechanically” sensitive discs, physically distend the anulus and simulate mechanical loading. In these discs, it is presumed that a mechanical deformation of the anulus is the inciting painful event.

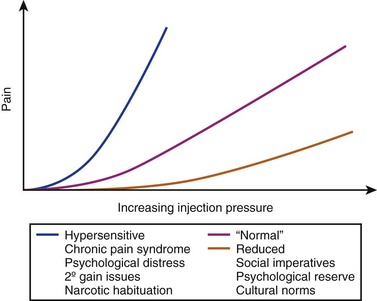

The use of pressure measurements has been postulated as a means to decrease the risk of false-positive injections. This assertion would be true if injections were rarely, if ever, positive at low pressures in subjects without true low back pain illness. Previous neurophysiologic considerations suggest that a pain and pressure profile for a given disc lesion may depend on individual pain sensitivity and local pain processes not related to the disc. Hypothetically, the pain and pressure profile may be depicted as shown in Figure 16–1. The presence of the factors enumerated in Table 16–2 thought to have a desensitizing effect would move the curve down and to the right, whereas factors that increase pain sensitivity may move the pain and pressure curve up and to the left.

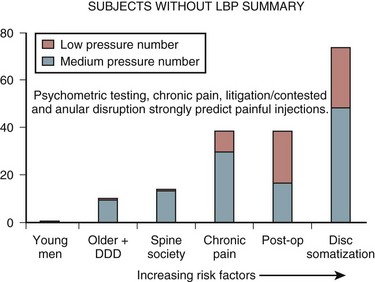

Experimental work has corroborated this hypothetical pain response. Discographic injections have been performed with pressure measurements in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic volunteers.15,29,35–37 Figure 16–2 shows the proportion of painful injections at low pressures in volunteers with varying risk factors for increased pain sensitization. It seems from these and other data38 that low-pressure injections are more likely positive in subjects with some type of chronic pain state, psychological distress, and, presumably, a generalized sensitization to irritable stimuli. An increased perception of pain at low-pressure injections seems to affect the pain response even when the chronic pain state is not in the low back region.

Evidence That Discography in Clinical Practice May Improve Outcomes

Many case series report that provocative discography is helpful in management of patients with chronic low back pain illness. These are uncontrolled studies, however, and the relationship of discography findings to clinical outcome after surgery is speculative: Good outcomes when encountered may be the result of nonspecific effects, natural history of the condition independent of diagnosis or treatment, scrupulous patient selection, or confounding findings on standard imaging studies. In a retrospective literature review, Cohen and Hurley39 compared outcomes of spinal fusions in studies that included discography with fusion outcomes without preoperative discography. The outcomes were not significantly different.

In the era before routine MRI use, Colhoun and colleagues40 retrospectively compared a series of fusions planned with and without preoperative discography. Evaluation methods of these patients having surgery in the 1970s and early 1980s did not include dynamic radiographs, MRI, or computed tomography (CT). The authors reported better results in the discography group. The two groups were not similar at baseline, however, and potential biases resulting in some patients having preoperative discography and others not having it were not examined. In the era before contemporary imaging techniques, this study suggested that discography may assist in the evaluation of patients before surgery. This is an extremely rare clinical scenario today and has little applicability to current evaluation protocols.

Madan and colleagues41 did a retrospective review of consecutive patients undergoing spinal fusion performed by the same surgeons, with and without preoperative discography. The two groups seemed well matched for demographic, psychometric, and radiographic features. At a minimum of 2-year follow-up, there was no significant difference in outcome between the two groups. The addition of discography to radiographs and MRI did not improve outcomes compared with radiographs and MRI alone.

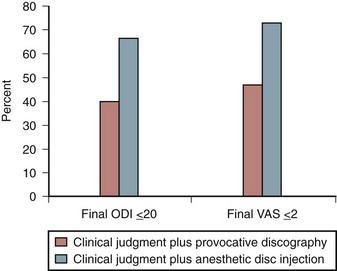

A more recent randomized clinical trial compared outcomes of subjects having single-level fusion based on preoperative evaluation using provocative discography with subjects having an anesthetic disc injection.42 These were in some respects subjects with best-case scenarios (no psychological distress, no depression, no workers’ compensation cases, and no traffic accident litigants). The discography was performed using low-pressure injections. The outcomes in the discography group were uniformly worse than the group using an anesthetic block to determine fusion (Fig. 16–3). A phase IV evaluation (based on evidence-based criteria as described by Sackett and Haynes26) of discography has not been performed to date (see Table 16–3).

Clinical Outcome as a “Gold Standard” in Provocative Discography

An attempt was made to control these variables (patient-specific variables and operative comorbidities) in a prospective controlled study of spinal fusion for presumed diagnoses of unstable spondylolisthesis versus discogenic pain diagnosed by discography. Identical operative techniques were used, and patients had no psychosocial comorbidities.43 Both groups included only highly selected patients with 6 to 18 months of severe low back pain, normal psychological testing, no previous or concomitant pain syndromes, and no workers’ compensation or personal injury claims. All patients had either positive discography at one level only and at low pressures (<20 psi) or unstable spondylolisthesis by strict radiographic criteria. All patients had been working full-time before their back problem, and no patient was taking daily narcotic medications.

For less “ideal” patients, provocative discography may be an extremely poor tool to select appropriate operative candidates. Freedman and colleagues,44 using CT and provocative discography to select a wide range of typical low back pain subjects for an intradiscal electrothermal therapy trial (including patients with psychometric distress and compensation claims), found no improvement at all compared with control subjects. Pauza and colleagues,45 in a similar intradiscal electrothermal therapy trial but excluding subjects with psychological abnormality, workers’ compensation claims, or litigation claims, found only slightly better outcomes: Most subjects did not have improvement better than expected by placebo.

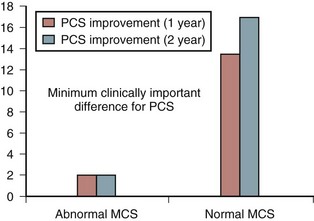

Even more striking, Derby and colleagues46 found such poor outcomes of spinal fusion after provocative discography in patients with abnormal mental component scores (MCS) on the SF-36 that the discography seemed to preselect patients who were extremely unlikely to have a satisfactory outcome. These results, illustrated in Figure 16–4, may be substantially worse than using alternative patient selection strategies without discography (e.g., radiographs, MRI, patient interview, or psychological screening).

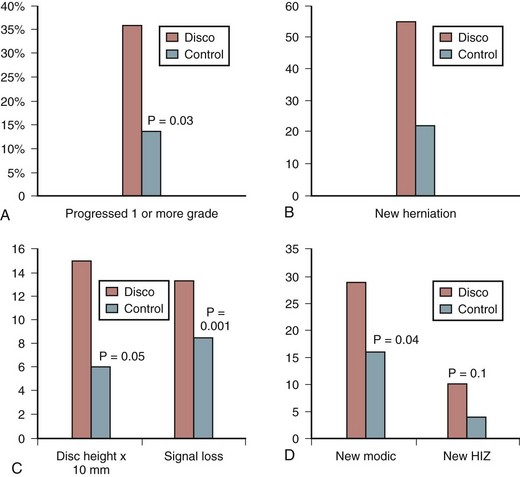

Complications

Carragee and colleagues50 performed a prospective, match-cohort study of disc degeneration progression over 10 years with and without baseline discography. The investigators performed a protocol MRI and L3-4, L4-5, and L5-S1 discography examination at baseline in 75 subjects without serious low back pain illness. The investigators enrolled a matched group at the same time and performed the same protocol MRI examination. Subjects were followed for 10 years. At 7 to 10 years after baseline assessment, eligible discography and control subjects underwent another protocol MRI examination. MRI examinations were scored for qualitative findings (Pfirrmann grade, herniations, endplate changes, and high-intensity zone). Loss of disc height and loss of disc signal were measured by quantitative methods (Fig. 16–5). The investigators found that modern discography techniques with small-gauge needle and limited pressurization resulted in accelerated disc degeneration, disc herniation, loss of disc height and signal, and development of reactive endplate changes compared with matched controls.

Conclusions Regarding Provocative Discography

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Sackett D, Haynes R. Evidence base of clinical diagnosis: The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ. 2002;324:539-541.

2 Carragee EJ, Tanner CM, Yang B, et al. False-positive findings on lumbar discography: Reliability of subjective concordance assessment during provocative disc injection. Spine. 1999;24:2542-2547.

3 Ohtori S, Kinoshita T, Yamashita M, et al. Results of surgery for discogenic low back pain: A randomized study using discography versus discoblock for diagnosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1345-1348.

4 Carragee EJ, Don AS, Hurwitz EJ, et al. The 2009 ISSLS Prize Winner. Does discography cause accelerated progression of degeneration changes in the lumbar disc: A ten-year matched cohort study. Spine. 2009;34:2338-2345.

5 Chou R, Loesser JD, Owens DK. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34:1066-1077.

1 Lindblom L. Diagnostic puncture of intervertebral disks in sciatica. Acta Orthop Scand. 1948;17:231-239.

2 Derby R, Guyer R, Lee S-H, et al. The rational use and limitations of provocative discography. ISIS Scientific News Letter. 2005;5:6-20.

3 Allan DB, Waddell G. An historical perspective on low back pain and disability. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1989;234:1-23.

4 Burton A. Spine update: Back injury and work loss: Biomechanical and psychosocial influences. Spine. 1997;22:2575-2580.

5 Burton A, Tillotson K, Main C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subacute low back trouble. Spine. 1995;20:722-728.

6 Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: A diagnostic sign of painful lumbar disc on magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Radiol. 1992;65:361-369.

7 Crock H. Internal disc disruption. Med J Aust. 1970;1:983-990.

8 Derby R, Howard MW, Grant JM, et al. The ability of pressure-controlled discography to predict surgical and nonsurgical outcomes. Spine. 1999;24:364-371. discussion 371-372

9 O’Neill C, Derby R, Kanderes L. Precision injection techniques for diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc disease. Semin Spine Surg. 1999;11:104-118.

10 Schwarzer A, Aprill C, Derby R, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic LBP. Spine. 1995;20:1878-1883.

11 Schwarzer A, Aprill C, Fortin J, et al. The relative contribution of the zygapophyseal joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1994;19:801-806.

12 Schwarzer A, Bogduk N. Letter to Editor. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disk disruption in patients with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:776.

13 Siddle P, Cousins M. Spinal pain mechanisms. Spine. 1997;22:98-104.

14 Carragee EJ, Tanner CM, Yang B, et al. False-positive findings on lumbar discography: Reliability of subjective concordance assessment during provocative disc injection. Spine. 1999;24:2542-2547.

15 Carragee EJ, Tanner CM, Khurana S, et al. The rates of false-positive lumbar discography in select patients without low back symptoms. Spine. 2000;25:1373-1380. discussion 1381

16 Gracely R, Dubner R, McGrath P. Narcotic analgesia: Fentanyl reduces the intensity but not the unpleasantness of painful tooth pulp stimulation. Science. 1979;203:1261-1263.

17 Lenz F, Gracely R, Romanoski A, et al. Stimulation in the somatosensory thalamus can reproduce both the affective and sensory dimensions of previously experienced pain. Nat Med. 1995;1:910-913.

18 Lenz FA, Gracely RH, Hope EJ, et al. The sensation of angina can be evoked by stimulation of the human thalamus. Pain. 1994;59:119-125.

19 Saal JSM. General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders—a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine. 2002;27:2538-2545.

20 Carragee EJ. Psychological screening in the surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:215-219.

21 North R, Kidd D, Zahurak M, et al. Specificity of diagnostic nerve blocks: A prospective, randomized study of sciatica due to lumbosacral spine disease. Pain. 1996;65:77-85.

22 O’Neill C, Kurgansky M. Subgroups of positive discs on discography. Spine. 2004;29:2134-2139.

23 Handwerker HO, Kobal G. Psychophysiology of experimentally induced pain. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:639-671.

24 Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: Divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84:65-75.

25 Carragee E, Tanner C, Vittum D, et al. Positive provocative discography as a misleading finding in the evaluation of low back pain NASS Proceedings. 1997. p 388

26 Sackett D, Haynes R. Evidence base of clinical diagnosis: The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ. 2002;324:539-541.

27 Schwarzer A, Wang S, Bogduk N, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: A study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:100-106.

28 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. The false-positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Pain. 1994;58:195-200.

29 Walsh T, Weinstein J, Spratt K, et al. Lumbar discography in normal subjects: A controlled prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1081-1088.

30 Block A, Vanharanta H, Ohnmeiss D, et al. Discographic pain report: Influence of psychological factors. Spine. 1996;21:334-338.

31 Ohnmeiss DD, Vanharanta H, Guyer RD. The association between pain drawings and computed tomographic/discographic pain responses. Spine. 1995;20:729-733.

32 Schellhas KP, Pollei SR, Dorwart RH. Thoracic discography: A safe and reliable technique. Spine. 1994;19:2103-2109.

33 Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Assessment of neck pain and its associated disorders. Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S101-S122.

34 Heggeness MH, Watters WCIII, Gray PMJr. Discography of lumbar discs after surgical treatment for disc herniation. Spine. 1997;22:1606-1609.

35 Carragee EJ, Chen Y, Tanner CM, et al. Provocative discography in patients after limited lumbar discectomy: A controlled, randomized study of pain response in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. Spine. 2000;25:3065-3071.

36 Derby R, Kim B-J, Lee S-H, et al. Comparison of discographic findings in asymptomatic subject discs and the negative discs of chronic LBP patients: Can discography distinguish asymptomatic discs among morphologically abnormal discs? Spine J. 2005;5:389-394.

37 Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller J, et al. Provocative discography in volunteer subjects with mild persistent low back pain. Spine J. 2002;2:25-34.

38 Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Parmar V, et al. Low pressure positive discography in subjects asymptomatic of significant LBP illness. Spine. 2006;31:505-509.

39 Cohen SP, Hurley RW. The ability of diagnostic spinal injections to predict surgical outcomes. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1756-1775.

40 Colhoun E, McCall IW, Williams L, et al. Provocation discography as a guide to planning operations on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:267-271.

41 Madan S, Gundanna M, Harley JM, et al. Does provocative discography screening of discogenic back pain improve surgical outcome? J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:245-251.

42 Ohtori S, Kinoshita T, Yamashita M, et al. Results of surgery for discogenic low back pain: A randomized study using discography versus discoblock for diagnosis. Spine. 2009;34:1345-1348.

43 Carragee EJ, Lincoln T, Parmar VS, et al. A gold standard evaluation of the “discogenic pain” diagnosis as determined by provocative discography. Spine. 2006;31:2115-2123.

44 Freeman BJ, Fraser RD, Cain CM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: Intradiscal electrothermal therapy versus placebo for the treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain. Spine. 2005;30:2369-2377. discussion 2378

45 Pauza KJ, Howell S, Dreyfuss P, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intradiscal electrothermal therapy for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. Spine. 2004;4:27-35.

46 Derby R, Lettice JJ, Kula TA, et al. Single-level lumbar fusion in chronic discogenic low-back pain: Psychological and emotional status as a predictor of outcome measured using the 36-item Short Form. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:255-261.

47 Carragee EJ, Chen Y, Tanner CM, et al. Can discography cause long-term back symptoms in previously asymptomatic subjects? Spine. 2000;25:1803-1808.

48 Korecki CL, Costi JJ, Iatridis JC. Needle puncture injury affects intervertebral disc mechanics and biology in an organ culture model. Spine. 2008;33:235-241.

49 Nassr A, Lee JY, Bashir RS, et al. Does incorrect level needle localization during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion lead to accelerated disc degeneration? Spine. 2009;34:189-192.

50 Carragee EJ, Don AS, Hurwitz EL, et al. 2009 ISSLS Prize Winner. Does discography cause accelerated progression of degeneration changes in the lumbar disc: A ten-year matched cohort study. Spine. 2009;34:2338-2345.