Chapter 18 Digitalis Toxicity

Digitalis Toxicity Vs. Digitalis Effect

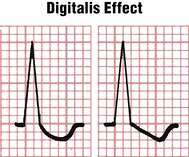

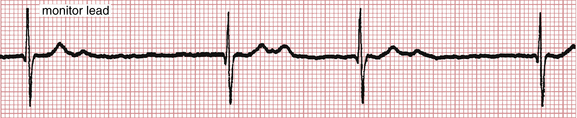

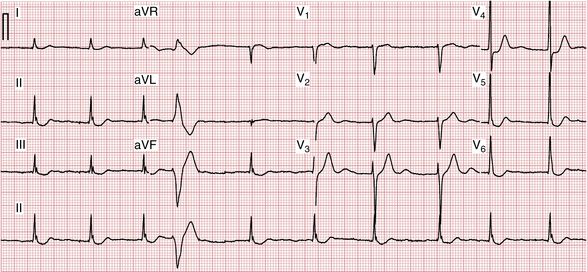

Digitalis toxicity refers to the arrhythmias and conduction disturbances (as well as the toxic systemic effects described later) produced by this class of drug. Digitalis toxicity should not be confused with digitalis effect. Digitalis effect (Figs. 18-1 and 18-2) refers to the distinct scooping (“thumbprinting” sign) of the ST-T complex (associated with shortening of the QT interval) typically seen in patients taking digitalis glycosides.

Note: The presence of digitalis effect, by itself, does not imply digitalis toxicity and may be seen with therapeutic drug concentrations. However, most patients with digitalis toxicity manifest ST-T changes of digitalis effect on their ECG.

Symptoms and Signs of Digitalis Toxicity

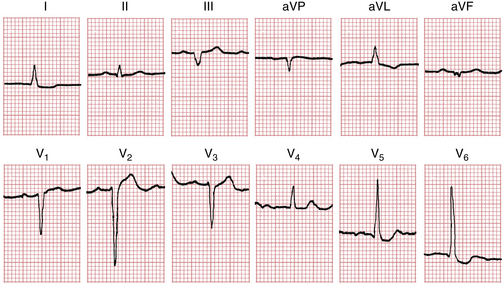

As a general clinical rule virtually any arrhythmia and all degrees of AV heart block can be produced by digitalis. However, a number of arrhythmias and conduction disturbances are commonly seen with digitalis toxicity (Box 18-1). In some cases, combinations of arrhythmias will occur, such as AF with a relatively slow ventricular response and frequent ventricular ectopy (Fig. 18-3).

BOX 18-1 Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances Caused by Digitalis Toxicity

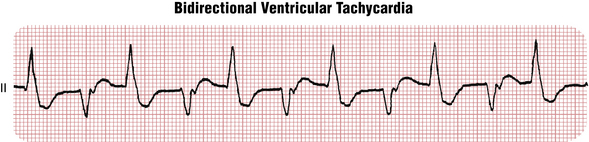

Two distinctive arrhythmias, when encountered, should raise concern for digitalis toxicity. The first is bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Fig. 18-4), a rare type of VT in which each successive beat in any lead alternates in direction. However, this rare arrhythmia may also be seen in the absence of digitalis excess (e.g., with catecholaminergic polymorphic VT; see Chapters 16 and 19).

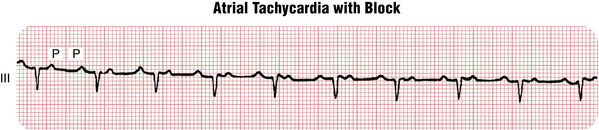

The second arrhythmia suggestive of digitalis toxicity is atrial tachycardia (AT) with AV block (Fig. 18-5). Not uncommonly, 2:1 AV block is present so that the ventricular rate is half the atrial rate. AV block is usually characterized by regular, rapid P waves occurring at a rate between 150 and 250 beats/min (due to increased automaticity) and a slower ventricular rate (due to increased AV block). Superficially, AT with block may resemble atrial flutter; however, when atrial flutter is present, the atrial rate is faster (usually 250 to 350 beats/min). Furthermore, in AT with block the baseline between P waves is isoelectric. Note: Most cases of AT with block encountered clinically are not due to digitalis excess, but it is always worth checking to rule out this possibility.

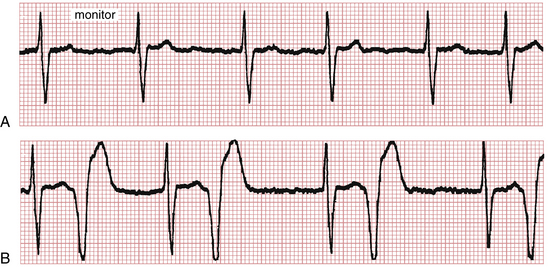

Digitalis toxicity is not a primary cause of AF or of atrial flutter with a rapid ventricular response. However, digitalis toxicity may occur in patients with these arrhythmias. In such cases the toxicity may be evidenced by marked slowing of the ventricular rate to less than 50 beats/min (Fig. 18-6) or the appearance of ventricular premature beats (VPBs). In some cases, the earliest sign of digitalis toxicity in a patient with AF may be a subtle regularization of the ventricular rate at the slower heart rate (Fig. 18-7).

Factors Predisposing to Digitalis Toxicity

A number of factors significantly increase the hazard of digitalis intoxication (Box 18-2).

Electrolyte Disturbances

A low serum potassium concentration increases the likelihood of certain digitalis-induced arrhythmias, particularly ventricular ectopy and AT with block. The serum potassium concentration must be checked periodically in any patient taking digitalis and in every patient suspected of having digitalis toxicity. In addition, both hypomagnesemia and hypercalcemia can be predisposing factors for digitalis toxicity. Electrolyte levels must be monitored in patients taking diuretics. In particular, furosemide can cause hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. Thiazide diuretics can also occasionally cause hypercalcemia

Coexisting Illness

Hypoxemia and chronic lung disease may also increase the risk of digitalis toxicity, probably because they are associated with increased sympathetic tone. Patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemia appear to be more sensitive to digitalis. Digitalis may worsen the symptoms of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, an inherited heart condition associated with excessive cardiac contractility. Patients with heart failure due to amyloidosis are also extremely sensitive to digitalis. In patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and AF (see Chapter 20), digitalis may cause extremely rapid transmission of impulses down the AV bypass tract, leading to a potentially lethal tachycardia (see Fig. 20-10). Patients with hypothyroidism appear to be more sensitive to the effects of digitalis. Women also appear to be more sensitive to digitalis. Because digoxin is excreted primarily in the urine, any degree of renal insufficiency, as measured by increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine concentrations, requires a lower maintenance dose of digoxin. Thus, elderly patients may be more susceptible to digitalis toxicity, in part because of decreased renal excretion of the drug.

Treatment of Digitalis Toxicity

Definitive treatment of digitalis toxicity depends on the particular arrhythmia. With minor arrhythmias (e.g., isolated VPBs, sinus bradycardia, prolonged PR interval, Wenckebach AV block, or AV junctional rhythms), discontinuation of digitalis and careful observation are usually adequate. More serious arrhythmias (e.g., sustained VT) may require suppression with an intravenous (IV) drug such as lidocaine. For tachycardias, potassium supplements should be given to raise the serum potassium level to well within normal limits.