13 Digestion and nutrition

History

Where growth or nutrition problems are suspected, take a careful feeding history (Table 13.1). Ask the parent to tell you everything the child has eaten and drunk in the last 24 hours, talking them through the meal times and asking about snacks and drinks between meals. Ask specifically how much milk and fruit juice drink (squash) is consumed and how many portions of fruit and vegetables are eaten daily. Are there battles over the child’s eating? Does the child eat alone or with other family members? A food diary kept by the parents over a 3- or 4-day period is sometimes useful.

| History | Comments |

|---|---|

| Which milk? | Breast or formula? If formula, note which one and details of reconstitution |

| How much feed? | In breast-fed infants, does the mother have a good milk supply? In formula-fed infants, note volumes offered and taken |

| How often? | Note the times of feeds in the previous 24 hours |

| How long does the feed take to complete? | |

| Characteristics of feeding? | Hungry, windy, apathetic, slow, sleepy, etc. |

Key symptoms of gastrointestinal problems in children are vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Symptoms of gastrointestinal problems

| Symptoms | Enquire about |

|---|---|

| Vomiting | Volume: dribble onto clothes or a full stomach |

| Nature: effortless, forceful (onto child or parent), projectile (several feet away), single vomit or run of vomits | |

| Frequency | |

| Relationship to feeds and posture | |

| Presence of blood or bile in vomit | |

| Diarrhoea | How often: a bowel action after each feed is common if breast-fed |

| Consistency: pure liquid, porridgey or mixed texture, undigested food | |

| Colour | |

| Presence of blood or mucus | |

| Constipation | How often; is wind passed between times |

| How difficult: straining to go or withhold, painful | |

| Soiling | |

| Child’s attitude to the problem | |

| Abdominal pain | Site/radiation |

| Pattern of onset and relationship to food, stress, medication | |

| Colicky or constant duration | |

| Waking the child at night (this implies an organic cause) |

Examination

General points

• Assess the child’s growth – is there poor weight gain?

• Look for jaundice or anaemia

• Assess the child’s muscle bulk – wasting of the gluteal muscles is seen in coeliac disease

• Is there any finger clubbing (see Table 10.3, p. 101)?

• Is there any evidence of assisted feeding such as a nasogastric tube or a gastrostomy?

Palpation

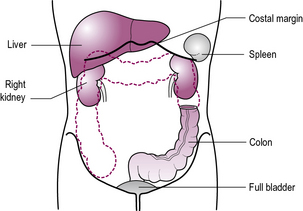

Look at the child’s face while palpating the abdomen. Start palpating at a point furthest away from any tenderness (see Figure 13.1). A reluctant child may be put at ease if their own hand is used, with the examiner ‘s hand overlying.

Feel for any tenderness. Is there any rebound tenderness or guarding?

Infant feeding

Breast-feeding

Problems and contraindications to breast-feeding are very few (see Table 13.3).

| Problem | Management |

|---|---|

| Feeding difficulties | Support for mother (health visitor, midwife, support groups) |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | Rare, require specialist advice |

| Maternal drug/alcohol abuse | Careful monitoring of infant |

| Maternal HIV | Contraindication in developed countries |

| Maternal medication | Check safety in BNF (British National Formulary) or with pharmacist |

| Prematurity | Expressed breast milk given via nasogastric tube |

| Tuberculosis | Contraindicated |

Diet for older children

Obesity

Obesity is a rapidly growing problem for children, their families and society. The 2008 Health Survey for England reported an obesity rate of 19.5% for children aged 11–15 years. Children living in poverty, from urban areas or from ethnic minority groups are at especially high risk of obesity. In the vast majority there is a simple imbalance between energy ingestion and energy expenditure. Factors contributing include high-energy snacks and fast foods, tendency for larger portion sizes, decreased levels of activity amongst children at school and social and cultural pressures. Children with simple obesity are usually tall for their age. Children who are growing poorly may have an endocrine cause for their obesity (Cushing’s syndrome, hypothyroidism or growth hormone deficiency – see Chapter 12).

Children with physical and/or learning disability are at increased risk of obesity. This is primarily a consequence of reduced ability to engage in physical activity, and, in some, is compounded by increased appetite. In rare instances, obesity is a characteristic of the underlying condition, notably Prader–Willi syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 274).

The vomiting infant

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Simple gastro-oesophageal reflux (as in Case 13.1) is usually a benign disorder which resolves spontaneously between 6 and 12 months of age as infants spend more time upright, solids are introduced, and natural anti-reflux mechanisms develop. Reassurance is the mainstay of treatment. Parents can try smaller volumes of milk, given more frequently, and positioning the infant with head elevated after feeds. Feed thickeners may help.

Investigation (rarely indicated)

• A barium swallow and meal will often confirm reflux and may identify abnormalities of oesophageal motility, strictures or hiatus hernias

• Endoscopy will enable confirmation of oesophagitis, and stricture formation. It is useful for diagnosis of oesophagitis associated with allergy (eosinophilic oesophagitis) which may not be associated with significant acid reflux

• A pH or impedance study will confirm the severity of acid reflux by demonstrating the duration of acid reflux into the lower oesophagus. This involves placing a pH probe just above the cardiac sphincter, in the lower oesophagus. It is vital to discontinue acid-blocking drugs (H2 receptor blockers or proton-pump inhibitors – PPIs) prior to the procedure.

Pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis (Case 13.2) describes a pathological thickening of the pyloric sphincter, which hypertrophies over the first few weeks of age. This causes obstruction of the gastric outlet. It affects 1 in 150 males and 1 in 750 female infants. It is more common in first-born children and in those with an affected parent.

Bilious vomiting in infancy

Bile-stained vomiting, as in Case 13.3, is an indicator of serious surgical pathology, and requires urgent assessment. Abdominal X-rays may reveal evidence of obstruction with fluid levels and dilated small or large bowel, or may show a displaced caecum indicating malrotation, as in this case. Upper or lower gastrointestinal contrast studies will clarify the picture. This congenital anomaly results in the mid-gut twisting on its mesentery, causing a volvulus, and potentially infarction from the mid-duodenum to the mid-transverse colon.

Congenital intestinal atresias most commonly affect the small bowel, particularly the duodenum. A significant number of affected infants have Down syndrome. Treatment is with resection of the atretic segment (see also Chapter 17, p. 260).

Hirschsprung’s disease occurs due to congenital absence of ganglion cells in the intramuscular and submucous layers of the large intestine, extending proximally from the anus. The affected bowel does not exhibit peristalsis, and proximal obstruction or enterocolitis (severe diarrhoea and abdominal distension) may occur. In the first instance, treatment is with a colostomy proximal to the aganglionic bowel (determined by intra-operative histology of ‘frozen sections’), followed later by restoration of bowel continuity, with a ‘pull-through’ procedure, typically around 1 year of age. Children with Down syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 273) are also at greatly increased risk of Hirschsprung’s disease.

Strangulated hernias may also produce bilious vomiting secondarily to intestinal obstruction.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis (as in Case 13.4) is a common infectious disease. Most cases are viral, and rotavirus causes over 50% of cases. Bacterial causes include Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli and Shigella, and may cause a dysentery-like picture, with blood and pus in the stool, and high fever, commonly with abdominal pain. However, abdominal pain is not usually a prominent feature in viral gastroenteritis. Infection with E. coli O157 may lead to gastroenteritis complicated by acute renal failure (see Chapter 11, p. 135).

Dehydration

Intussusception

Intussusception (Case 13.5), in which the bowel partly invaginates, leading to ischaemia, characteristic ‘redcurrant jelly stools’ and severe episodes of pain with pallor, and vomiting, often causes diagnostic confusion. The highest incidence is seen around 6–9 months of age.

Abdominal pain

Acute appendicitis

The boy in Case 13.6 had acute appendicitis and surgery was performed as soon as possible. Where possible, emergency surgery is avoided. Trials are under way investigating antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis, with a view to avoiding or deferring surgery. The history described is typical but it can be difficult, especially in preschool children, or if the appendix is unusually sited. Ultrasound or CT scanning may be required. Other causes of acute abdominal pain must be considered – see Box 13.1 and Table 13.4.

| Cause | Key clinical features |

|---|---|

| Renal or ureteric pain | Pain experienced laterally or posteriorly |

| Gastritis or gastro-oesophageal reflux | Epigastric or chest pain |

| Peptic ulceration | Night pain |

| Spinal or back problems | Lateral pain |

| Signs over the spine (tenderness, limited movement) | |

| Liver or gall bladder disease | Right hypochondrial pain |

| Jaundice | |

| Constipation | Usually presents with constipation rather than pain; pain better if bowels are open |

| Gynaecological problems | Suprapubic or iliac fossa pain |

| Periodic pain (monthly) | |

| Abdominal migraine | Acute attacks +/− pallor and vomiting |

Infantile colic

In Case 13.7, if the history and examination reveal no worrying features it is highly likely that the baby has colic.

Non-specific abdominal pain

Abdominal pains like those in Case 13.8 affect 10% of children and can have a variety of labels including NSAP (non-specific abdominal pain), functional abdominal pain and sensitive bowels. Many children will have no worrying features in the history, or on examination, and do not require investigations. In others, inflammatory bowel disease, food intolerances or other causes (see Table 13.4) may need to be excluded.

Constipation

Constipation (as in Case 13.9) is common and causes much distress to children and families. There may be a genetic tendency, but poor fluid and fibre intake, fear of defecation and development of a megarectum exacerbate the problems. Megarectum develops when the rectum remains over-distended and the sensations of needing to defecate are lost. Involuntary soiling may then occur as liquid stool escapes past the hard impacted stool and through a stretched anal sphincter. This is very distressing to children and their families and the risks of social isolation and school avoidance are real. Constipation is rarely due to a coeliac disease or food intolerance, endocrine causes (such as hypothyroidism) or neurological causes. In short-segment Hirschsprung’s disease, symptoms date back to the neonatal period.

Chronic diarrhoea

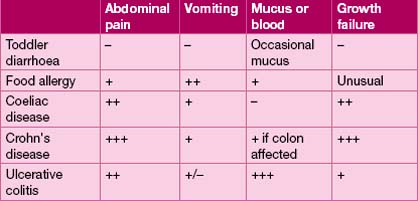

Chronic diarrhoea in children has diverse causes, ranging from toddler diarrhoea to inflammatory bowel disease (see Table 13.5).

Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease may be broadly classified according to clinical presentation:

• Typical – the commonest presentation in young children

• Atypical, in which abdominal signs or symptoms are minimal, and there are extra-intestinal clinical features such as dermatitis herpetiformis

• Silent, in which serology is positive and biopsy findings diagnostic, but the patient is asymptomatic (often detected on screening of susceptible individuals)

• Latent, in which individuals are HLA-susceptible, may have positive serology, but biopsy is not diagnostic.

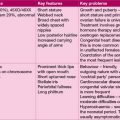

Most infants and children with coeliac disease present with typical symptoms, including diarrhoea, which is typically pale, fatty, offensive and ‘porridge-like’ in nature. The clinical appearance is characteristic (see Figure 13.2). Other symptoms are described in Table 13.6.

| Type of presentation | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Classical presentation (9–18 months) | Pale, irritable, failure-to-thrive, abdominal distension, buttock wasting |

| Early presentation (<9 months) | Vomiting or constipation |

| Late presentation (childhood–adult) | Iron deficiency anaemia, short stature, fatigue, abdominal pain |

| Screening (in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes or a strong family history) | Subtle symptoms or none at all |

Jaundice in children

Jaundice arises from elevation of serum bilirubin. Haemolytic disorders cause jaundice (see Chapter 7, p. 60), or it may arise from impaired clearance of bilirubin in hepatocellular dysfunction, as occurs with hepatitis, or from biliary obstruction such as biliary atresia.

Congenital causes of jaundice

Bilirubin arises from breakdown of haem. It is metabolized in the liver by the glucuronyl transferase enzyme system to the conjugated form that is excreted in bile. Defects of this enzyme system result in unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. Severe defects, due to autosomal recessive inheritance, result in Crigler–Najjar syndrome with extremely severe jaundice occurring at birth, and often resulting in choreo-athetoid cerebral palsy (kernicterus) (see Chapter 14, p. 197). Gilbert’s syndrome arises from a mild conjugation defect, resulting in intermittent mild jaundice with fatigue, usually triggered by illness. It is relatively common, and harmless. Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia occurs in Dubin–Johnson and Rotor syndromes, which are due to defective hepatic excretion of conjugated bilirubin. Aside from jaundice, patients are usually asymptomatic.

The infant with obstructive jaundice

The young infant with obstructive jaundice (as in Case 13.10) requires urgent evaluation to exclude biliary atresia. In biliary atresia there is progressive obliteration of the extra- and intra-hepatic bile ducts, leading to hepatocellular injury, with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Surgery to construct a bile conduit (Kasai procedure) is performed as soon as possible. If surgery is unsuccessful, then liver failure results, requiring liver transplantation. If bile drainage is achieved, then the progression of liver disease may be slowed, although ascending cholangitis, malnutrition due to fat malabsorption, and portal hypertension leading to oesophageal varices and consequent gastrointestinal haemorrhage are common complications.

Galactosaemia (Case 13.11) results from an inability to metabolize galactose. Toxic metabolites accumulate with resultant hepatic and renal toxicity and cataracts. High levels of galactose-1-phosphate provide an ideal substrate for E. coli sepsis, which complicates half of cases. It is treated by elimination of all sources of lactose and galactose, which includes breast and bottled milks. This rare condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Despite early treatment, learning difficulties are common, notably verbal dyspraxia (see Chapter 4, p. 30). Girls are almost always infertile due to premature ovarian failure. Cataracts may occur, due to accumulation of the galactose metabolite, galactitol, in the lens of the eyes, and ophthalmological surveillance is required.

Hepatitis

Acute hepatitis

However, infection is commonly asymptomatic or subclinical.

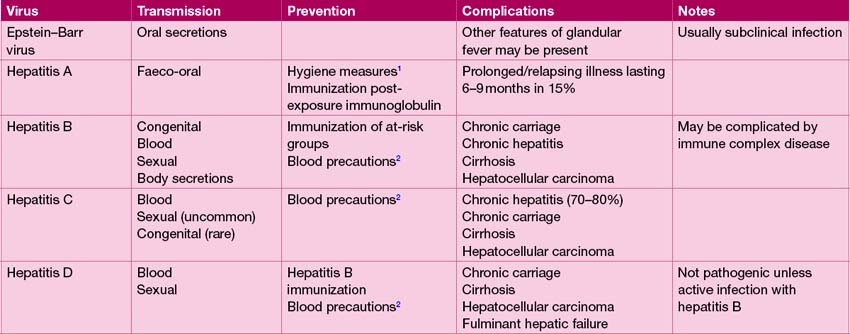

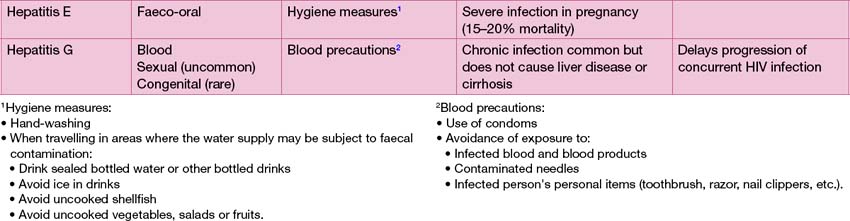

Drug reactions, paracetamol poisoning and a range of infections, most commonly viral, can cause hepatitis. The principal causes of viral hepatitis are summarized in Table 13.7. Hepatitis A is by far the most common cause of viral hepatitis. The maximum period of infectivity occurs in the 2 weeks prior to onset of jaundice. There is little systemic upset but often abdominal pain, vomiting and loss of appetite, which may last several weeks. Travellers to endemic areas, or exposed contacts, such as other family members at risk of infection, should receive hepatitis A immunization.

Fulminant hepatic failure

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is fortunately rare, and manifests with encephalopathy, hepatocellular dysfunction (impaired coagulation, hypoalbuminaemia with oedema, acidosis, hypoglycaemia), renal failure and sepsis. The commonest cause in the UK is paracetamol poisoning (see Appendix I, p. 299), followed by fulminant viral infections. Other causes include metabolic diseases such as Wilson’s disease, Reye’s syndrome and disorders of fatty acid metabolism.