2 Difficulty swallowing and pain on swallowing

Case

A 28-year-old male presents with a 10 year history of intermittent (roughly 2 monthly), non-progressive dysphagia for solids, but not liquids. He perceives bolus holdup in the neck. Sips of water help resolve minor dysphagia episodes. He has had two visits to the Accident and Emergency Department in 10 years for endoscopic disimpaction of meat boluses, but the endoscopist reported the oesophagus appeared entirely normal and the bolus had passed spontaneously on both occasions. He has had two barium radiographs performed in this time; both were normal. He denies heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation or weight loss. He suffered from asthma as a child. He takes no medications and has no prior medical history. He denies deglutitive cough and post-nasal regurgitation, and has no need for multiple swallows to clear liquid from the pharynx.

Pain on Swallowing (Odynophagia)

Odynophagia is the symptom of pain on swallowing, generally arising from irritation of an inflamed or ulcerated mucosa by the swallowed bolus during its passage through the oesophagus. Mucosal injury causing odynophagia can be caused by infective (viral or fungal) oesophagitis or by mucosal ulceration secondary to corrosive agents (e.g. tablets or reflux oesophagitis) (Box 2.1). The symptom of odynophagia almost invariably warrants endoscopy to elucidate the cause, which may need biopsy confirmation.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Reflux oesophagitis can cause odynophagia. The patient typically describes a sensation of pain or discomfort coincident with passage of the bolus through the oesophagus, sometimes combined with a sense of transient bolus hold-up. The sense of bolus arrest can dominate the symptom complex if the oesophagitis has progressed to stricture formation, but is not infrequently perceived even in the absence of a stricture. For a detailed account of investigation and management of reflux disease, refer to Chapter 1.

Dysphagia

Causes of dysphagia

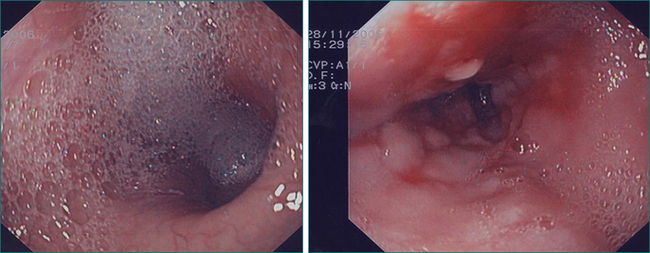

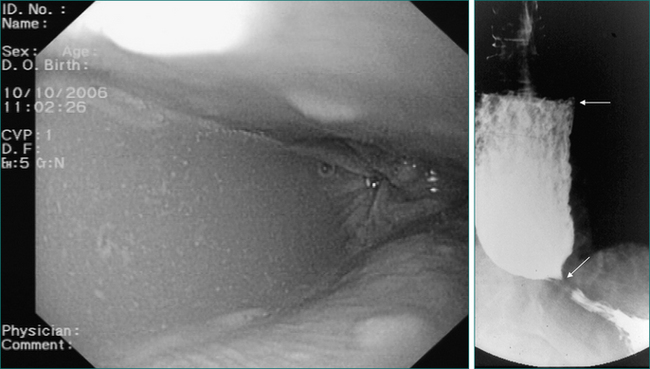

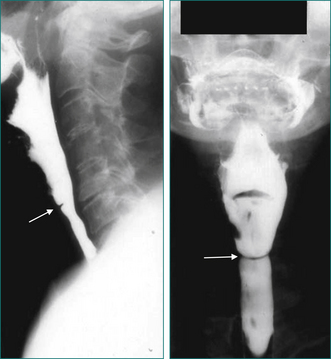

Oral-pharyngeal dysphagia is most commonly related to neuromuscular dysfunction, most commonly stroke (Box 2.2). Head and neck surgery and radiotherapy, for malignant disease, are also very commonly associated with oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Other structural disorders causing oral-pharyngeal dysphagia include strictures, mucosal webs (Fig 2.1) and pharyngeal diverticulum.

Figure 2.1 Mucosal web in the cervical oesophagus seen in lateral view (left) and anteroposterior view (right).

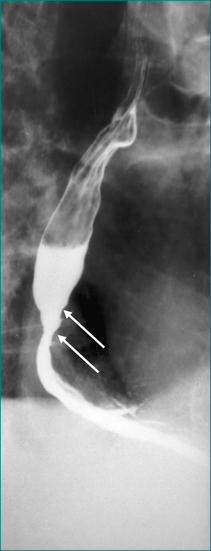

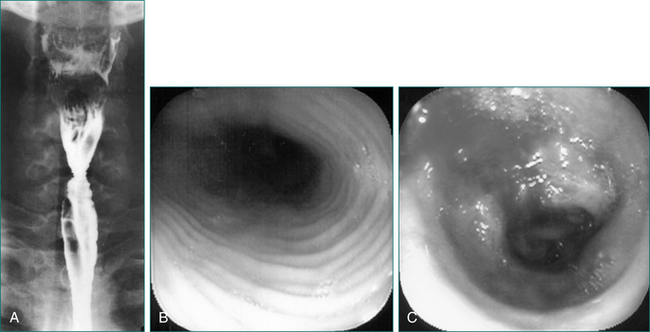

Because gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is prevalent, peptic oesophageal strictures are a very common cause of oesophageal dysphagia (Figs 2.2 and 2.3, Box 2.3). In these cases, there is frequently a prior history of reflux symptoms. Mucosal rings, such as the Schatzki ring at the cardio-oesophageal junction, are a common cause of intermittent oesophageal dysphagia. Malignant oesophageal obstruction is usually evident on history by virtue of a short history of rapidly progressive dysphagia and significant weight loss (Fig 2.4).

Approach to the assessment of the patient with dysphagia

Is it true dysphagia?

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty with the act of swallowing. The purely sensory symptom of globus can be equated inappropriately with difficulty swallowing by the patient. Globus is a non-painful sensation of a lump or fullness in the throat in which deglutitive food bolus transport is unimpaired. Indeed, globus sensation is usually alleviated by eating and is most noticeable between meals. The patient with globus sensation generally only requires otolaryngological evaluation to exclude local inflammatory or infiltrative disorders followed by explanation and reassurance. Some cases can be reflux-related and a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy is reasonable although response rates to this approach are modest and variable.

Age of onset, duration of dysphagia, frequency and progression

The duration of symptoms is often an important clue to whether the underlying cause is benign or malignant or whether it is due to a recent, acute event such as a stroke. Malignant dysphagia usually presents with a short history of progressive dysphagia over weeks or a few months and is frequently associated with weight loss. A sudden onset of dysphagia, often in association with other neurological symptoms or signs, usually indicates a neurological cause such as stroke. Frequent dysphagia, which is progressive and predominantly for solids, is more likely to indicate an underlying structural disorder such as a peptic stricture or tumour.

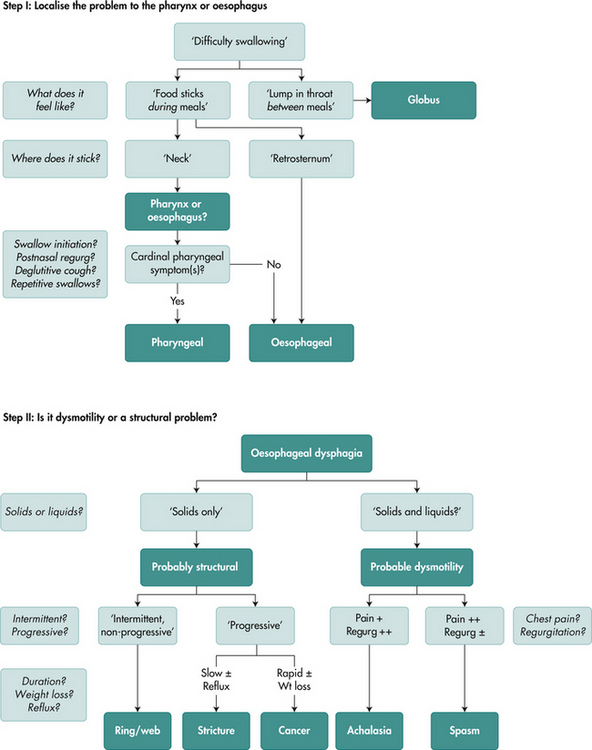

An algorithmic approach to determine site and likely aetiology of dysphagia

With the abovementioned information to hand, the next logical step is to define more precisely the anatomical location of the problem. This can be achieved in most instances from the history (Fig 2.5).

Symptoms specific for oesophageal dysphagia

If, based on the above, one strongly suspects an oesophageal cause for dysphagia, the next step is to determine whether the cause is a structural lesion or a motor disorder (Fig 2.5). Again, this can be achieved by the line of questioning in the following step-wise fashion.

Is there an underlying related or causative disease?

Oral-pharyngeal dysphagia usually has a neurological basis. A prior history of stroke is often obtained. Symptoms of bulbar muscle dysfunction or other brain stem symptoms (such as vertigo, nausea, vomiting, hiccup, tinnitus, diplopia or drop attacks) should be sought. The patient may complain of tremor, ataxia or unsteadiness, which might indicate an underlying movement disorder or may describe muscular weakness suggestive of myopathy (Box 2.2).

Physical examination of the patient with dysphagia

Eyes

Thyrotoxic eye signs should be looked for. Ptosis might indicate a myopathy or myasthenia. Unilateral ptosis, if associated with Horner’s syndrome (descending sympathetic tract), is typical of lateral medullary infarction causing pharyngeal dysphagia. In addition to dysphagia, the lateral medullary (Wallenberg’s) syndrome typically involves hoarseness (10th nerve), vestibular dysfunction (nystagmus, vertigo, vomiting, diplopia and tinnitus), cerebellar limb ataxia, contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation over half the body (spinothalamic tract), and hiccups.

Investigation of dysphagia

Investigation of suspected oral-pharyngeal dysphagia

The initial investigation should be a dynamic, radiographic examination—the videoradiographic swallow study of the oral-pharyngeal phase. This examination should be complemented by static films, but video recordings are mandatory as the motor events of the oral-pharyngeal phase are too complex and too rapid to be resolved by simple observation of fluoroscopy or x-ray films. Static films are important in detecting mucosal defects and structural lesions such as strictures, rings, pouches, webs (Fig 2.1) and tumours.

Laboratory tests are useful in confirming suspected underlying primary diseases that may cause oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Serum creatine phosphokinase level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies, acetylcholine receptor antibodies and thyroid function tests will give a clue to most acquired myopathies, but electromyogram and muscle biopsy may also be necessary as 20% of cases of myositis will have normal biochemistry.

Investigation of suspected oesophageal dysphagia

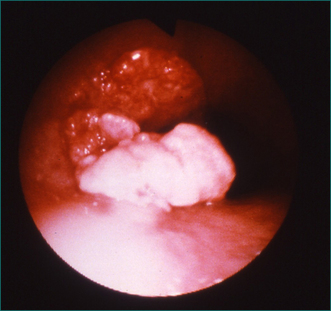

With a few exceptions, endoscopy should be the first investigation in cases of suspected oesophageal dysphagia. Endoscopy is more sensitive than radiology in detecting mucosal disease. It also provides an opportunity to obtain biopsies and to combine a diagnostic with therapeutic procedure in cases where dilatation is required. One of the deficiencies of endoscopy in the assessment of dysphagia is that it cannot reliably diagnose motility disorders, although the endoscopic finding of a dilated oesophagus containing fluid or salivary residue is highly suggestive of dysmotility (Fig 2.6). Endoscopy does not always reliably pick up all benign structural abnormalities capable of causing dysphagia. This is because an accurate estimation of the narrow calibre oesophagus is not always possible at endoscopy. Hence, a negative endoscopy does not always exclude a structural cause of dysphagia. If a structural oesophageal abnormality is suspected strongly on history and the oesophagus has a normal macroscopic appearance, oesophageal biopsies should be taken to check for eosinophilic oesophagitis, which is commonly associated with one or more mucosal rings (Fig 2.8).

In the investigation of oesophageal dysphagia, there are two situations in which a barium swallow should precede endoscopy—a suspected oesophageal ring and suspected oesophageal dysmotility. Preliminary barium swallow findings in these circumstances may permit definitive treatment of a ring or achalasia at the initial endoscopy, or dictate manometry prior to endoscopy if achalasia is suspected (Fig 2.6). In the patient with a typical history of an oesophageal ring (see above), a barium swallow can be an extremely useful adjunct to endoscopy, because mucosal rings are frequently not apparent endoscopically. An appropriately tailored barium swallow study, including prone-oblique views and if necessary a marshmallow swallow, will usually clearly demonstrate a ring and/or the site of bolus hold-up causing the patient’s symptoms. The ring can then be dilated, even if it is not visible to the endoscopist, at the subsequent endoscopy.

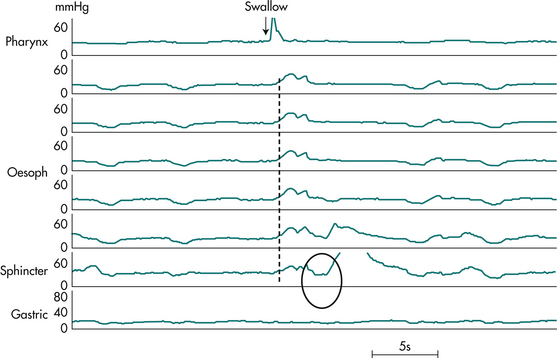

Oesophageal manometry is usually reserved for cases in whom endoscopy and radiology have failed to achieve a diagnosis. Manometry is the only way to diagnose achalasia with certainty; its manometric features are oesophageal aperistalsis, hypertonia and failure of the lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation during swallowing (Fig 2.7). The manometric hallmark of diffuse oesophageal spasm is synchronous oesophageal contractions in at least 10% of water swallows in an oesophagus, which can demonstrate peristalsis. Additional features present to a variable extent include repetitive waves (swallow-induced or spontaneous); high amplitude contractions; and prolonged contractions (of more than 6 seconds). The scleroderma oesophagus demonstrates complete aperistalsis and absent lower oesophageal sphincter tone, both being due to profound smooth muscle degeneration in the distal oesophagus.

Figure 2.7 Manometry tracing from patient with oesophageal achalasia. Shown are pressures at 5 cm intervals along the oesophagus, and from the lower oesophageal sphincter and stomach, during a 5 mL water swallow. Note the hypertensive sphincter (pressure 30 mmHg) and the failure of lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation (circled). There is a complete loss of peristalsis. In its place is a synchronous low amplitude pressure wave (dashed line) with identical waveform along the entire oesophageal length, indicative of lack of lumen occlusion of a dilated oesophagus (as seen in barium radiograph, Fig 2.6).

Treatment of dysphagia

Treatment of oesophageal dysphagia

Oesophageal strictures, rings and webs are generally successfully treated by endoscopic dilatation. This is most commonly achieved by passing graduated sizes of Silastic™ (e.g. Savary-Gilliard®) or balloon dilators over an endoscopically placed guide wire. The underlying cause of the stricture must also be treated. Severe reflux disease causing stricture should be managed with potent acid suppression with a proton pump inhibitor. The more refractory cases may require antireflux surgery. Difficult strictures often require repeated dilatations.

In the case of one or more oesophageal rings, eosinophilic oesophagitis must always be considered and diagnosis is achieved with endoscopic biopsies. Eosinophilic oesophagitis should be treated in the first instance with the topical (swallowed) steroid fluticasone. Controlled trials have shown comparable efficacy between topical and systemic steroids in eosinophilic oesophagitis, but the former is preferred as it has fewer systemic effects. Steroid therapy in eosinophilic oesophagitis may obviate the need for oesophageal dilatation. However, a proportion of cases, particularly with longstanding disease, may still require dilatation to achieve adequate symptomatic relief and avoid episodic complete bolus impaction. Great care must be exercised in these cases as the rings are often relatively tight and significant postdilatation tears are not infrequent (Fig 2.8).

Diffuse oesophageal spasm is best treated with smooth muscle relaxants such as nitrates and calcium channel blockers. If symptoms are relatively infrequent, sublingual nitrates to abort an episode of chest pain can be useful. Refractory cases with debilitating symptoms can be treated surgically by long oesophageal myotomy, which is effective in 50–70% of cases.

Key Points

Bohm M., Richter J.E. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: overview, current limitations, and future direction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(10):2635-2644.

Cook I.J., Kahrilas P.J. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines: management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(2):455-478.

Francis D.L., Katzka D.A. Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:369-374.

Pandolfino J.E., Kaharilas P.J. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:207-208.

Spechler S.J. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:229-232.