Chapter 39 Difficult Cannulation and Sphincterotomy

Introduction

In the era of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has become a procedure with a primarily therapeutic focus (e.g., access to and through stenoses, removal of stones, or drainage of cysts).1–4 If used as a diagnostic procedure, ERCP is more often performed to sample tissue by the introduction of cytology brushes or biopsy forceps or to facilitate direct cholangioscopy. Major papilla sphincterotomy is mandatory in most cases to achieve adequate access for the introduction of instruments and drainage catheters. General issues related to cannulation and sphincterotomy have already been discussed in Chapter 37. The present chapter focuses on variations of the standard technique that can be used by advanced endoscopists. The variations in technique have to be performed with caution and adapted to the individual case. Important general issues are discussed first.

Proper Endoscope

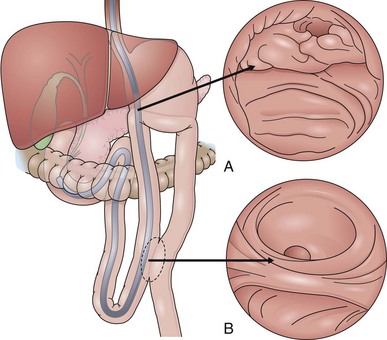

Access to and cannulation of the papilla in case of a Billroth II (BII) resection (Figs. 39.1 and 39.2) is generally possible with a comparable success rate using a prograde or a side-viewing endoscope; this is described later.5–7 Gastroscopes work only in a few usually older BII patients without enteroenteric anastomosis, but gastroscopy may be helpful for initial inspection and orientation of the anastomoses. In patients with a very long afferent loop and in patients after gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis, a pediatric colonoscope or enteroscope longer than 170 cm is needed in case of a forward-viewing endoscopic approach. Although the forward-viewing instrument facilitates intubation of the afferent loop at the gastroenteric anastomosis, it typically provides only a tangential view of the papilla.8

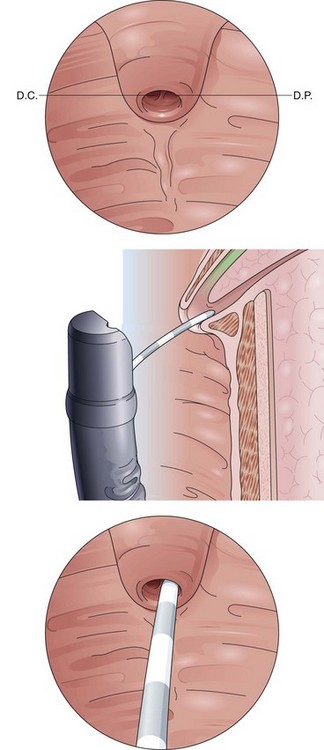

Fig. 39.2 Billroth II cannulation. View of the papilla from below with inverted anatomy.

(Modified from Soehendra N, Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, et al: Therapeutic endoscopy: color atlas of operative techniques for the gastrointestinal tract, New York, 1997, Thieme Medical Publishers.)

The duodenoscope offers the advantage of improved visual orientation to the ampulla. The elevator is helpful to manipulate and maintain accessories. A duodenoscope is preferred by many endoscopists if applicable.5,8 In a difficult anatomic situation with a steep afferent loop, it can be helpful first to place a 0.035-inch, 450-cm guidewire (polytetrafluoroethylene-coated standard Seldinger wire; PNB Medical, Denmark) into the blind proximal end of the duodenal stump under radiographic control as a pathfinder for the side-viewing instrument.

Locating the Papilla

Although the natural position of the papilla is on the inner side of the duodenal C-loop in the midportion of the descending duodenum, it may be difficult to find in some instances. The papilla may be located toward the lower portion, which often requires a very “long” endoscope position. The papilla can be cloaked by duodenal folds, and often only the frenulum, as a caudal longitudinal extension, indicates that the papillary orifice may be close. In the search for the papilla, an atraumatic ERCP catheter or sphincterotome can be helpful to lift and separate folds. Duodenal diverticula have to be inspected carefully. One way to expose the inner side of the diverticulum is to push the mucosa gently from the outer rim of the diverticular ring caudally with an ERCP catheter. The papillary orifice often appears by being pulled from the inner side of the diverticulum toward the edge of the opening. Submucosal injection into the bottom of the diverticulum has been described to lift the papillary orifice. However, one should keep in mind the very thin wall of the diverticulum with the risk of potentially severe complications owing to needle perforation and retroperitoneal leak and a potential edematous compression of the papillary orifice.9

In rare cases, it can take 20 minutes or longer to find the papilla. Sometimes, the papilla is located more proximally. This situation occurs after Billroth I resection. Very rarely, the papilla is located in the duodenal bulb. An edematous duodenum after an acute attack of chronic pancreatitis or advanced cancer of the head of the pancreas can make successful localization and cannulation of the papilla impossible. A radiologically guided percutaneous-transhepatic rendezvous procedure and endoscopic ultrasound–guided puncture into the biliary system are options in these cases.10–14

Park and coworkers15 described using methylene blue to find the minor papilla orifice in patients with a complete pancreas divisum. After spraying dye onto the area of the papilla, pancreatic secretions wash away the dye from papillary orifice. Intravenous secretin (Secrelux, Sanochemia Diagnostics, D-41460 Neuss) can help in this case to stimulate pancreatic secretion and to identify the pancreatic orifice for minor papilla cannulation. Secretin is expensive, however, and should not be given in case of pancreatic obstruction or acute pancreatitis.

Cannulation

A well-sedated patient is the prerequisite for a smooth intervention. Before cannulation, the papilla should be observed carefully, and the endoscopist should imagine the natural course of the CBD. A long papillary roof delineating the distal bile duct above the horizontal fold (plica horizontalis) may be helpful in determining its axis and course (Fig. 39.3). For cannulation of the CBD, the papilla should be viewed from below, and the catheter direction should be steep and within the axis of the papilla. Curving the distal end of the catheter upward often facilitates achievement of this angle and eases biliary cannulation. The catheter tip is introduced into the papillary orifice and gently pushed forward while the elevator is lifted and the bile duct is cannulated. For primary pancreatic duct cannulation (Fig. 39.4), the endoscope position remains at the level of the papilla, and the catheter direction is roughly horizontal. Although the course of the pancreatic duct leads toward the 5 o’clock position viewed from directly in front of the papilla, in our experience it can be helpful, in a native papilla, to turn the small wheel of the endoscope forward and cannulate the papillary orifice from the right to the left followed by only gentle injection of contrast material.

Catheter versus Sphincterotome Cannulation

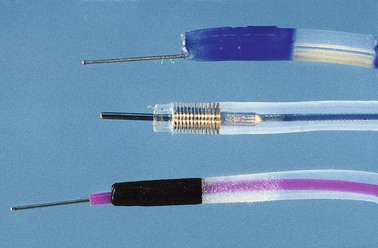

The primary use of a catheter or a sphincterotome for biliary cannulation is controversial. The traditional first choice is a regular tapered 6-Fr catheter with a 4-Fr tip accepting a 0.035-inch wire that is used for biliary cannulation of the papilla and may serve for easier intrahepatic cannulation in biliary stenoses. The advantage of a prebent standard catheter over a 6-Fr sphincterotome is the higher flexibility and even less traumatic access owing to a high sensitivity even for narrow papillary channels. However, the use of a regular sphincterotome to initiate cannulation of the bile duct potentially allows variability and improvement of the vertical angle in which the bile duct is cannulated alongside the axial alignment.16

New devices are constantly being developed to improve the success rate of ERCP.16,17 Two studies evaluated the use of a new steerable catheter (SwingTip; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to achieve bile duct cannulation. Igarashi and coworkers18 reported successful cholangiography in 175 of 195 cases (90.5%) with a standard catheter; using the SwingTip catheter in cases in which the standard catheter failed, it was possible to carry out cholangiography in 11 of 17 patients (64.7%), increasing the overall success rate to 95%. Laasch and colleagues17 conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the success rate in performing cholangiography and bile duct cannulation with three different catheters: a standard ERCP cannula, a short-nosed sphincterotome, and the SwingTip device. The study included 312 patients at two tertiary referral centers. Both steerable catheters were significantly better than the standard catheter for performing cholangiography (P = 0.038), but no differences were found between the SwingTip cannula and the sphincterotome. Steerable catheters were also more effective for deep cannulation of the bile duct, but the improvement did not reach statistical significance. Steerable catheters succeeded in 26% of the cases in which the standard cannula failed. The study also compared differences in the results obtained from an expert and a trainee endoscopist using the three catheters. Trainees experienced greater benefit from using steerable catheters, whereas experts were quicker in performing cholangiography and deep cannulation with the SwingTip device. The overall success rate was 97%, and pancreatitis occurred in 5.3% of cases.

Wire-Guided Cannulation

When routine maneuvers fail, the next step may be the use of a wire-guided sphincterotome.16,19 The endoscopist positions the tip of the sphincterotome at the presumed mouth of the biliary orifice, and the assistant gently turns the wire. The J-tip of a 0.035-inch atraumatic hydrophilic guidewire (J-Terumo; Terumo Corp, Japan) is usually rotated in a clockwise direction. The tip of even the softest wire becomes stiff if forcefully pushed out of a catheter or if the sphincterotome lumen is pressed against tissue. One should gently press the sphincterotome or catheter toward the suspected CBD direction and leave enough room for the tip to flex slightly while the wire is rotated with a torquing device. When this technique fails, the options are to abort the procedure and review the indication or alternatives, such as proceed to access sphincterotomy or referral to another operator. A good reason for the endoscopist to stop at this point is limited experience and a low case volume.

Precut Sphincterotomy

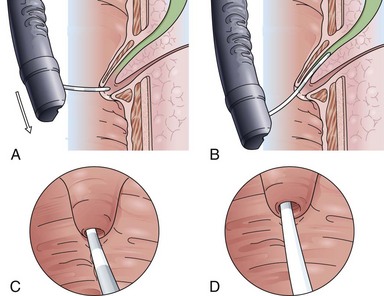

The classic Erlangen-type precut sphincterotome is shaped like a standard sphincterotome, but its distal end is cut off to just below the cutting wire. Modifications include catheters with a 1- to 2-mm nose at the distal tip. The precut sphincterotome is placed in the papillary orifice and slightly lifted and gently pushed forward in the direction of the bile duct with diathermic current application. This technique can be termed an “entry” cut to distinguish it from the following two freehand needle-knife techniques (Fig. 39.5).

Although needle-knife sphincterotomy has been considered a risk factor for ERCP-induced complications such as pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation, series from centers with a high frequency of needle-knife precut sphincterotomies show that in experienced hands the needle-knife procedure does not have a higher complication rate.19,20 The most common needle-knife technique is to place the needle tip into the papillary orifice, lift the upper lip of the papilla with slight tension on the needle-knife, and give short bursts of cutting current in the biliary direction. Another approach is sequential dissection of the roof of the papilla, starting at the papillary orifice with careful sweeping cuts of about 5 to 7 mm to dissect the papillary mound in a stepwise fashion. Subsequent dissections up to the plica horizontalis should allow separation of the cut edges of mucosa and submucosa with recognition of the red sphincter muscle. After careful opening of the papillary apparatus in the common sphincteric area, the circular structure of the biliary sphincter with an often dark central point indicates the desired orifice. It is now helpful to switch to a tapered cannula and probe the biliary sphincter atraumatically. A gush of bile to indicate successful bile duct access should not routinely be expected and usually occurs only in the case of an intrapapillary stone obstruction.

Billroth II Resection

Following the minor curvature of the stomach, the two orifices of the afferent and efferent loop appear in the form of an “8.” The upper “o” of the “8” is usually the access to the afferent loop (see Fig. 39.1). Often, the angle of the fixation of the afferent loop to the stomach is very steep, and sometimes the opening of the afferent loop is seen only from below looking back in inversion to the stomach. One can easily slip from the afferent loop into the efferent loop—the endoscope takes on a U-shaped configuration. After only a brief loss of visualization, one may easily enter and follow the efferent limb for long distances without recognizing the error. When it seems impossible to intubate a steep afferent loop, one should exclude a terminal side-to-side gastrojejunostomy. This is the case in Whipple’s resection of the head of the pancreas with a single jejunal loop attached to the stomach and Roux-en-Y anastomosis for biliary and pancreatic drainage. One or two 30-mL syringes filled with contrast material and injected (sequentially) directly through the instrumentation channel can help to find the course of a steep afferent loop. In the case of a terminal gastrojejunostomy such as in Whipple’s resection, there is only a 1- to 2-cm blind end in the usual position of the afferent loop.

Advancing the scope toward the papilla, the afferent loop must be probed carefully and lifted with the tip of the endoscope. There is a significantly higher perforation rate of the small intestine, especially at the site of the anastomosis, leading to a higher overall complication rate for ERCP in cases of BII resection and Roux-en-Y anastomosis compared with ERCP in standard anatomy.7,21 As described previously, the use of a forward-viewing instrument such as a gastroscope or pediatric colonoscope is preferable in the case of an unclear anatomic situation. Sometimes there is a corkscrewlike path of the first 5 cm entering the afferent limb at the gastroenteric anastomosis, which may be challenging for passage with a duodenoscope. Primary placement of a 4.5-m guidewire into the afferent limb via a prograde instrument is an option in these situations. The endoscope is withdrawn leaving the guidewire in place, which is followed endoscopically and radiographically side to side with the duodenoscope.

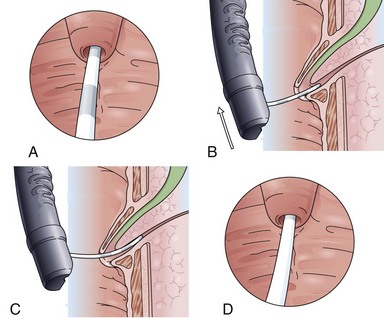

Concerning the ERCP procedure itself in a patient after BII resection or with a Roux-en Y anastomosis and intact duodenal anatomy (e.g., after tumor gastrectomy), the anatomy at the level of the papilla is reversed (see Fig. 39.1A). The papilla is approached from below instead of from above because usually the bile duct is now located at the 5 o’clock position. The pancreatic duct is reached via the 11 o’clock position. Using a side-viewing endoscope with the advantage of an elevator withdrawing the endoscope about 2 to 3 cm with a very flat tangential position toward the papilla often helps intubate the CBD. With regard to the reversed anatomy, the catheter tip should not be curved but should be straight.

The classic option for BII sphincterotomy is a special Billroth II sphincterotome (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC); the cutting wire is guided similar to in a standard sphincterotome for a path of 20 mm in the outside of the catheter. By advancing the handle apparatus, the cutting wire protrudes to form a “shark-fin” configuration. The cutting wire is advanced forward over a guidewire in the direction of the plica horizontalis in the middle of the papillary mound. However, this technique is not always as simple as it seems because the wire easily rotates and slips toward the duodenal side of the wall, and back rotation using a duodenoscope is not always that easy. Many endoscopists prefer the needle-knife technique on the stent. Variations of the latter technique include self-shaping a standard sphincterotome to allow a similar function as the commercial BII sphincterotome by overextending the cutting wire.22

Roux-en-Y Anastomosis and Double-Balloon or Single-Balloon Enteroscopy for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

The papilla can be reached using a pediatric colonoscope in only about 10% of all patients needing ERCP after gastrectomy.5 For these cases, double-balloon enteroscopy and more recently single-balloon enteroscopy are good options.23,24 Double-balloon enteroscopy can lead to successful ERCP in about 80% of cases with BII resections with long afferent limb and Roux-en-Y postsurgical anatomy.25–28 For these cases, the therapeutic type of double-balloon enteroscope is preferred (Fujinon EN450T5; Fujinon Corp, Saytama, Japan).29,30 However, special ERCP accessories with excess length have to be used. More recently, the prototype of a short 152-cm double-balloon enteroscope for ERCP (Fujinon EC450BI 5; Fujinon Corp) has been introduced. One advantage is the ability to use standard ERCP instruments, in particular, self-expandable metal stents and sphincterotomes.28 Training in double-balloon enteroscopy ERCP technique ex vivo has proved helpful for beginners.31

Complications

Similar to success rates, complications associated with ERCP, and especially sphincterotomy, are volume-dependent. In sphincterotomy, bleeding, pancreatitis, and perforation are the most concerning complications. Bleeding may be attributed to an aberrant vessel in the roof of the papilla. The latter may occur as a variation of the normal anatomy in about 2.5% of cases.32

The reported incidence of pancreatitis occurring after ERCP and sphincterotomy ranges from 1.3% to 24.4% in nonselected series.16,33,34 This varying incidence likely reflects differences in patient populations, indications, and endoscopic expertise and different definitions for pancreatitis and methods of data collection. Numerous patient-related factors are recognized as risks for post-ERCP pancreatitis in more recent large prospective studies, comprising 1966 cases, including the combination of female gender, normal serum bilirubin levels, and recurrent abdominal pain suggesting sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and previous post-ERCP pancreatitis.32 Combinations of risk factors can substantially increase the odds ratio (e.g., to 16.2 for a difficult cannulation in a female patient with normal bilirubin). Among technique-related risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis, biliary sphincter balloon dilation, difficult cannulation, sphincter of Oddi manometry, and pancreatic sphincterotomy have also been recognized as significant risk factors.

Because the case mix in nonselected series does not significantly differ in the different studies, it is logical to assume that the different criteria adopted for defining post-ERCP pancreatitis play a key role in the reported wide variation of incidence reported for this complication. The occurrence and duration of pain and the amplitude of serum amylase after ERCP are critical points in the definition of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Although a consensus conference identified 24-hour persisting pain associated with hyperamylasemia greater than three times the upper reference limit as an indicator of pancreatitis, these two parameters are considered in a different manner in the studies available up to now. In a prospective study in which the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis was calculated by using the most widely used criteria, for both occurrence and duration of pancreatic pain and serum amylase amplitude, the incidence of postprocedure pancreatitis ranged from 1.9% to 11.7% depending on the criteria adopted.32,35

Pancreatic Stents for Prevention of Pancreatitis following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

As potential prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis, pancreatic drainage with stents or nasopancreatic tubes can reduce the risk or severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis in selected cases. In particular, patients with pancreatic sphincter hypertension benefit from a temporary endoprosthesis.33,36 As a consequence, the implantation of a protective pancreatic stent (4-Fr to 7-Fr) has been postulated for prevention of pancreatitis after difficult cannulation or sphincterotomy or both.

Aizawa and Ueno37 retrospectively analyzed the efficacy of temporary pancreatic duct stent placement for prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic sphincter dilation for removal of bile duct stones. Endoscopic sphincter dilation was performed in 38 patients with a mean number of 2.2 ductal stones and a mean maximum stone size of 12 mm. Bile duct clearance was achieved in 37 patients after 52 sessions, using mechanical lithotripsy in 58% of the cases. Biliary drainage was augmented in 13 cases to prevent cholangitis. The success rate of insertion of pancreatic 5-Fr stents was 95%. Endoscopy was repeated after 3 days for removal of biliary and pancreatic prostheses, with the exception of a few cases in which there was spontaneous passage. In a historical control group of 92 patients, the success rates for endoscopic sphincter dilation without pancreatic stents were not provided. Medical treatment, such as oral administration of nifedipine 3 hours before treatment or subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin, showed no benefit compared with placebo.35

Cheon and associates38 investigated the use of orally administered nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in 207 evaluable patients randomly assigned to receive diclofenac, 50 mg, or placebo by mouth 30 to 90 minutes before and 4 to 6 hours after ERCP. The overall incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis was 16.4%. It occurred in 17 of 102 patients in the control group (16.7%) and in 17 of 105 patients in diclofenac group (16.2%). There was no significant difference between the groups in the frequency or severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis in overall and high-risk patients; however, the power of the study was less than 45%.

Elmunzer and colleagues39 performed a meta-analysis concerning the use of rectally administered diclofenac. They found four randomized controlled trials enrolling 912 patients. Meta-analysis of these studies showed a pooled relative risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis after prophylactic administration of NSAIDs of 0.36 (95% confidence interval 0.22 to 0.60); patients who received NSAIDs in the periprocedural period were 64% less likely to develop pancreatitis and 90% less likely to develop moderate to severe pancreatitis. The pooled number needed to treat with NSAIDs to prevent one episode of pancreatitis was 15 patients. No adverse events attributable to the use of NSAIDs were reported in any of the clinical trials. However, the investigators concluded that additional multicenter studies are needed for confirmation before widespread adoption of this strategy. At the present time, the best options for the clinician to reduce the risk of pancreatic complications after ERCP are awareness of specific patient-related and procedure-related risk factors before the procedure, referral of elective high-risk cases to an expert center, and, eventually, 4-Fr to 5-Fr nonpolyethylene protective pancreatic stent placement.

1 Kondo S, Isayama H, Akahane M, et al. Detection of common bile duct stones: Comparison between endoscopic ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiography, and helical-computed-tomographic cholangiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:271-275.

2 Freeman ML, Sielaff TD. A modern approach to malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003;3:187-201.

3 Rocca R, De Angelis C, Castellino F, et al. EUS diagnosis and simultaneous endoscopic retrograde cholangiography treatment of common bile duct stones by using an oblique-viewing echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:479-484.

4 Topal B, Van de Moortel M, Fieuws S, et al. The value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in predicting common bile duct stones in patients with gallstone disease. Br J Surg. 2003;90:42-47.

5 Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W, et al. Endoscopic access to the papilla of Vater for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:69-73.

6 Costamagna G. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy in Billroth II patients: A demanding technique for experts only? Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:306-309.

7 Costamagna G, Mutignani M, Perri V, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1994;57:155-162.

8 Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee MH, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and needle-knife sphincterotomy in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy: A comparative study of the forward-viewing endoscope and the side-viewing duodenoscope. Endoscopy. 1997;29:82-85.

9 Soehendra N, Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, et al. Therapeutic endoscopy: Color atlas of operative techniques for the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1997.

10 Nagashima I, Takada T, Shiratori M, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation as a therapeutic option for choledocholithiasis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:252-254.

11 Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, et al. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: Report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246-251.

12 Hung HH, Chen TS, Tseng HS, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage is an effective rescue therapy for biliary complications in liver transplant recipients who fail endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:395-401.

13 Matsushita M, Uchida K, Okazaki K. EUS-guided suprapapillary puncture for safe selective biliary access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:865-866. author reply 866–867

14 Ignee A, Baum U, Schuessler G, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholangiography and cholangiodrainage (CEUS-PTCD). Endoscopy. 2009;41:725-726.

15 Park SH, de Bellis M, McHenry L, et al. Use of methylene blue to identify the minor papilla or its orifice in patients with pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:358-363.

16 Bourke MJ, Costamagna G, Freeman ML. Biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Core technique and recent innovations. Endoscopy. 2009;41:612-617.

17 Laasch HU, Tringali A, Wilbraham L, et al. Comparison of standard and steerable catheters for bile duct cannulation in ERCP. Endoscopy. 2003;35:669-674.

18 Igarashi Y, Tada T, Shimura J, et al. A new cannula with a flexible tip (Swing Tip) may improve the success rate of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2002;34:628-631.

19 Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, et al. A prospective randomized trial of cannulation technique in ERCP: Effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2008;40:296-301.

20 Katsinelos P, Mimidis K, Paroutoglou G, et al. Needle-knife papillotomy: A safe and effective technique in experienced hands. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:349-352.

21 Wright BE, Cass OW, Freeman ML. ERCP in patients with long-limb Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy and intact papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:225-232.

22 Hintze RE, Veltzke W, Adler A, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy using an S-shaped sphincterotome in patients with a Billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:74-78.

23 Chu YC, Su SJ, Yang CC, et al. ERCP plus papillotomy by use of double-balloon enteroscopy after Billroth II gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1234-1236.

24 Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, et al. Single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y anastomosis (with video). Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:93-99.

25 Koornstra JJ, Fry L, Monkemuller K. ERCP with the balloon-assisted enteroscopy technique: A systematic review. Dig Dis. 2008;26:324-329.

26 Koornstra JJ. Double balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography after Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Case series and review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2008;66:275-279.

27 Fahndrich M, Sandmann M, Heike M. A facilitated method for endoscopic interventions at the bile duct after Roux-en-Y reconstruction using double balloon enteroscopy. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:335-338.

28 Chu YC, Yang CC, Yeh YH, et al. Double-balloon enteroscopy application in biliary tract disease—its therapeutic and diagnostic functions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:585-591.

29 Dellon ES, Kohn GP, Morgan DR, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with single-balloon enteroscopy is feasible in patients with a prior Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1798-1803.

30 Monkemuller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, et al. ERCP using single-balloon instead of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2008;40(Suppl 2):E19-E20.

31 Maiss J, Diebel H, Naegel A, et al. A novel model for training in ERCP with double-balloon enteroscopy after abdominal surgery. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1072-1075.

32 Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434.

33 Freeman ML. Pancreatic stents for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: For everyday practice or for experts only? Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:940-944.

34 Guda NM, Freeman ML. 30 years of ERCP and still the same problems? Endoscopy. 2007;39:833-835.

35 Rabenstein T, Fischer B, Wiessner V, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin does not prevent acute post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:606-613.

36 Freeman ML. Pancreatic stents for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1354-1365.

37 Aizawa T, Ueno N. Stent placement in the pancreatic duct prevents pancreatitis after endoscopic sphincter dilation for removal of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:209-213.

38 Cheon YK, Cho KB, Watkins JL, et al. Efficacy of diclofenac in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in predominantly high-risk patients: A randomized double-blind prospective trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1126-1132.

39 Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Elta GH, et al. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut. 2008;57:1262-1267.