W1 Difficult Airway Management for Intensivists

Supraglottic Airway Placement: Before Procedure

Supraglottic Airway Placement: Before Procedure

Indications

Equipment

After Procedure

After Procedure

Suggested Reading

Bougie-Assisted Intubation: Before Procedure

Bougie-Assisted Intubation: Before Procedure

Indications

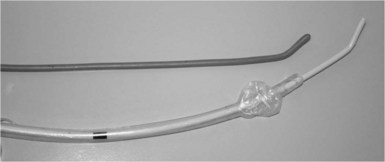

Equipment

Anatomy

Anatomy

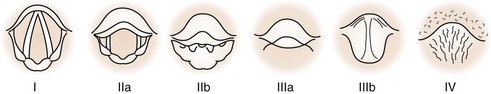

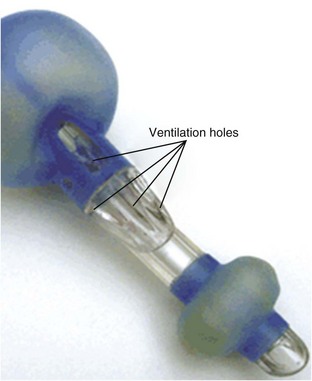

Though the bougie is capable of assisting intubation in nearly all airway situations except when “no view” is possible, it is most commonly used as an adjunct with Grade IIb, IIIa, and IIIb laryngeal views. Even when the laryngoscopy reveals a full view (grade I), the bougie may be useful when the hypopharyngeal opening is narrow (OSA, obesity, swelling) and passing the ETT may actually obstruct the view of the glottic opening. In this case, the narrower, more colorful tracheal tube introducer can be passed into the trachea with little visual obstruction taking place. Conversely, the floppy epiglottis is a challenge that may be technically difficult with many different airway adjuncts. The bougie may either be used to elevate the floppy epiglottis or be maneuvered around by virtue of the Coude tip. Though useful, the success rate is often less than 50%, and other alternatives may be needed (intubating laryngeal mask airway [ILMA], videolaryngoscope [VL], fiberoptic bronchoscope [FOB]) (Figure W1-7).

Procedure

Procedure

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Complications

Suggested Reading

Use of the Intubating Model of the LMA for Emergency Airway Rescue (Fastrach) ILMA: Before Procedure

Use of the Intubating Model of the LMA for Emergency Airway Rescue (Fastrach) ILMA: Before Procedure

Anatomy

Anatomy

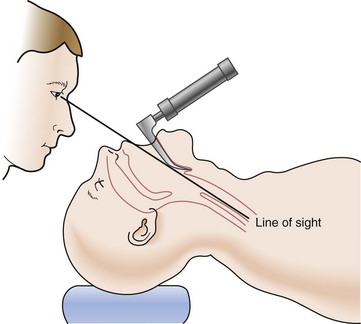

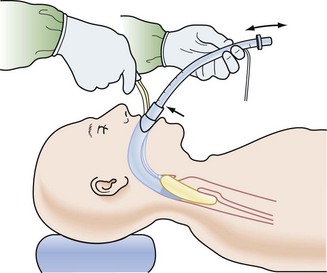

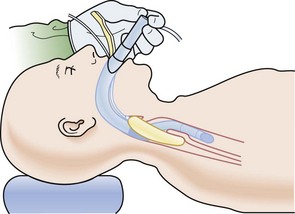

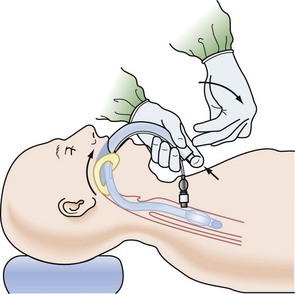

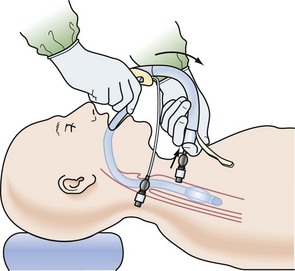

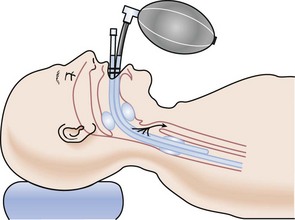

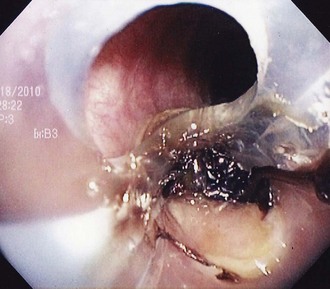

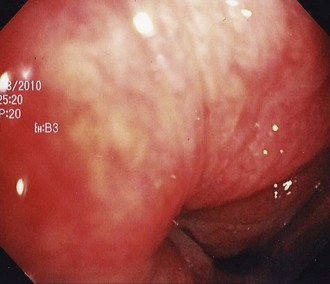

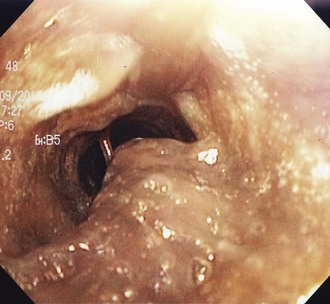

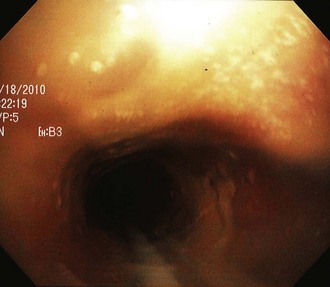

In general, placement of the ILMA can be performed in the exaggerated “sniff” position or the other extreme, a neutral cervical spine. The ILMA is lubricated and then passed along the roof of the mouth across the hard to soft palate, encouraging smooth advancement along the posterior throat so as to minimize getting hung up on the epiglottis or causing its downfolding. The distal tip of the ILMA typically comes to lie with its distal tip in the cricopharyngeal region. Unfortunately, the cuff end may buckle over on itself, come to lie over the glottic opening, or be displaced in a contorted position that impedes effective ventilation and oxygenation (Figures W1-9 through W1-16).

Procedure

Procedure

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Outcomes and Evidence

Outcomes and Evidence

Suggested Reading

Retrograde Wire Intubation: Before Procedure

Retrograde Wire Intubation: Before Procedure

Indications

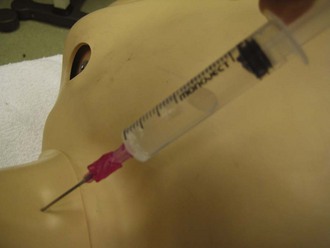

Anatomy

Anatomy

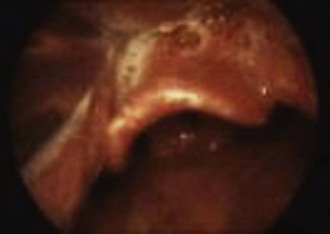

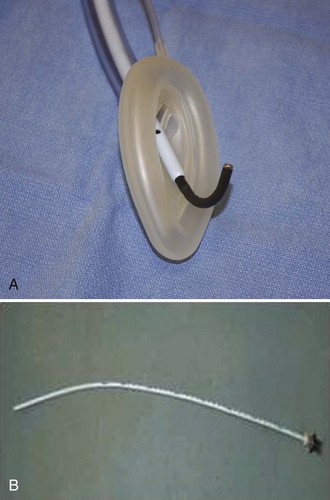

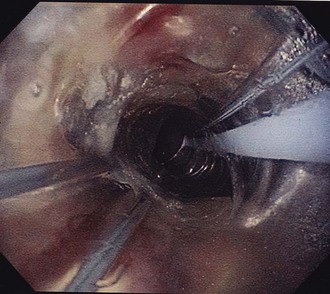

The cricothyroid membrane is located between the superior thyroid cartilage and the inferior cricoid ring. The cricothyroid membrane is located just 1.5 to 2 cm below the vocal cords, so care must be practiced when advancing a needle caudad, as the underside of the vocal cords could be impaled. Passing the ETT over the wire or obturator/wire may be met with resistance at the 16- to 17-cm depth, as the ETT tip may impinge on the vocal cords or arytenoids. This is the inherent danger of passing the ETT blindly over the wire or obturator/wire assembly. The location of the distal tip (having met resistance) may or may not be at the position below the vocal cords. This is the challenge of the retrograde wire method; knowing the location of the ETT tip is unknown when the decision is made to remove the wire. If the ETT tip is erroneously positioned above the glottis, then the access to the airway is denied with wire removal; hence, the advantage of using the FOB as an intubation guide (Figure W1-17).

Procedure

Procedure

After Procedure

After Procedure

Suggested Reading

Needle Cricothyrotomy with Transtracheal Jet Ventilation: Before Procedure

Needle Cricothyrotomy with Transtracheal Jet Ventilation: Before Procedure

Indications

Contraindications

Procedure

Procedure

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Outcomes and Evidence

Outcomes and Evidence

Suggested Reading

Needle and Surgical Cricothyrotomy: Before Procedure

Needle and Surgical Cricothyrotomy: Before Procedure

Indications

Contraindications

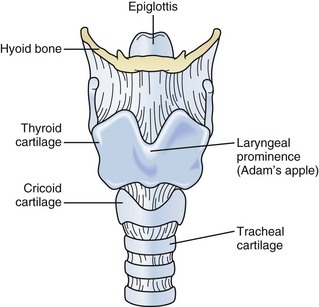

Anatomy

Anatomy

The thyroid cartilage consists of two approximately quadrilateral-shaped laminae of hyaline cartilage that fuse anteriorly to form the laryngeal prominence. The anterior superior edge of the thyroid cartilage, the laryngeal prominence, is known as the Adam’s apple and is usually easily seen in men. It is probably the most important landmark in the neck when performing a cricothyrotomy. The cricoid cartilage is shaped like a signet ring with the shield located posteriorly and forms the inferior border of the cricothyroid membrane. The thyroid cartilage forms the superior border of the cricothyroid membrane (Figure W1-27).

Procedure: Conventional Approach

Procedure: Conventional Approach

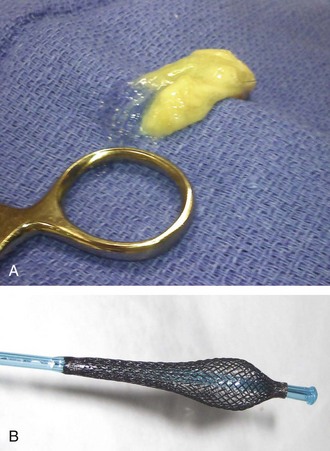

Procedure: Stylet-Dilator Method

Procedure: Stylet-Dilator Method

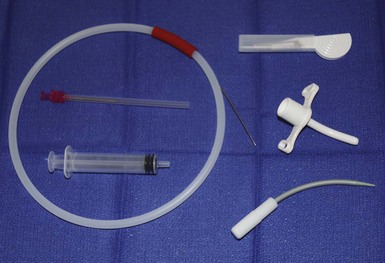

Procedure: Seldinger Technique–Melker Cook Critical Care

Procedure: Seldinger Technique–Melker Cook Critical Care

Procedure: Surgical Approach–Rapid Four-Step or Modified Three-Step

Procedure: Surgical Approach–Rapid Four-Step or Modified Three-Step

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Outcomes and Evidence

Outcomes and Evidence

Suggested Reading

Esophageal-Tracheal Combitube: Before Procedure

Esophageal-Tracheal Combitube: Before Procedure

Contraindications

Equipment

Procedure: Combitube

Procedure: Combitube

Procedure: King Laryngeal Tube

Procedure: King Laryngeal Tube

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Suggested Reading

Evaluation of a Cuff Leak in the ICU: Before Procedure

Evaluation of a Cuff Leak in the ICU: Before Procedure

Indications

Contraindications

Procedure

Procedure

Suggested Reading

Extubation of the Difficult Airway: Before Procedure

Extubation of the Difficult Airway: Before Procedure

Indications

Contraindications

Anatomy

Anatomy

Procedure

Procedure

TABLE W1-1 Time Frame* for Maintaining the Well-Tolerated Airway Exchange Catheter

| Difficult airway only, no respiratory issues or airway swelling | 1-4 hours |

| Difficult airway, no direct respiratory issues, potential for airway swelling | 2-6 hours |

| Difficult airway, cardiopulmonary issues, multiple extubation failures | 2-24 hours |

* Time frame will vary according to patient condition, airway assessment, and tolerance of the presence of the airway exchange catheter.

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Suggested Reading

Videolaryngoscope-Assisted Intubation: Before Procedure

Videolaryngoscope-Assisted Intubation: Before Procedure

Indications

Videolaryngoscopy (VL)

Equipment

(Figures W1-43 through W1-50)

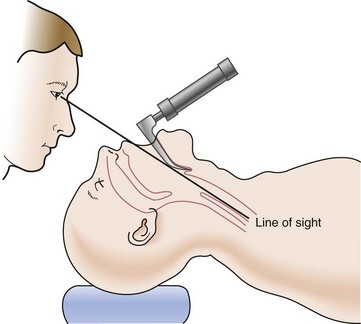

Figure W1-48 Combining direct laryngoscopy with the optical stylet to achieve laryngeal visualization.

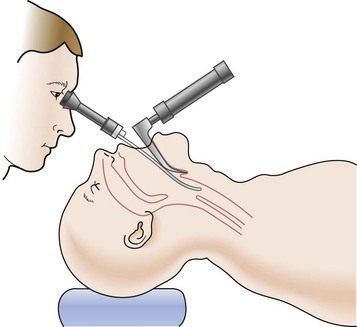

Figure W1-50 Same patient as Figure W1-49 but with video-laryngoscope-assisted view, allowing operator full view of epiglottis, arytenoids, and glottic opening.

Procedure

Procedure

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Outcomes and Evidence

Outcomes and Evidence

Phillips SS, Celenza A. Comparison of the Pentax AWS videolaryngoscope with the Macintosh laryngoscope in simulated difficult airway intubations by emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2010 Oct 13. Epub

Corso RM, Piraccini E, Terzitta M, et al. The use of Airtraq videolaryngoscope for endotracheal intubation in Intensive Care Unit. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010 Jul 1. Epub

Noppens RR, Möbus S, Heid F, et al. Evaluation of the McGrath Series 5 videolaryngoscope after failed direct laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2010 Jul;65(7):716-720.

Hirabayashi Y, Fujita A, Seo N, et al. Distortion of anterior airway anatomy during laryngoscopy with the GlideScope videolaryngoscope. J Anesth. 2010 Jun;24(3):366-372.

Xue FS, Xiong J, Yuan YJ, et al. Pentax-AWS videolaryngoscope for awake nasotracheal intubation in patients with a difficult airway. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Apr;104(4):505.

Hirabayashi Y, Otsuka Y, Seo N. GlideScope videolaryngoscope reduces the incidence of erroneous esophageal intubation by novice laryngoscopists. J Anesth. 2010 Apr;24(2):303-305.

Uslu B, Damgaard Nielsen R, Kristensen BB. McGrath videolaryngoscope for awake tracheal intubation in a patient with severe ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Jan;104(1):118-119.

Cavus E Cavus E, Kieckhaefer J, Doerges V, et al. The C-MAC videolaryngoscope: first experiences with a new device for videolaryngoscopy-guided intubation.

Walker L, Brampton W, Halai M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intubation with the McGrath Series 5 videolaryngoscope by inexperienced anaesthetists. Br J Anaesth. 2009 Sep;103(3):440-445.

Thong SY, Shridhar IU, Beevee S. Evaluation of the airway in awake subjects with the McGrath videolaryngoscope. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009 May;37(3):497-498.

Stroumpoulis K, Pagoulatou A, Violari M, et al. Videolaryngoscopy in the management of the difficult airway: a comparison with the Macintosh blade. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009 Mar;26(3):218-222.

Komatsu R, Kamata K, Hoshi I, et al. Airway scope and gum elastic bougie with Macintosh laryngoscope for tracheal intubation in patients with simulated restricted neck mobility. Br J Anaesth. 2008 Dec;101(6):863-869.

Lim HC, Goh SH. Utilization of a GlideScope videolaryngoscope for orotracheal intubations in different emergency airway management settings. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009 Apr;16(2):68-73.

Cooper RM. Complications associated with the use of the GlideScope videolaryngoscope. Can J Anaesth. 2007 Jan;54(1):54-57.

Cooper RM, Pacey JA, Bishop MJ, et al. Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2005 Feb;52(2):191-198.

Mort TC. Tracheal tube exchange: feasibility of continuous glottic viewing with advanced laryngoscopy assistance. Anesth Analg. 2009 Apr;108(4):1228-1231.

* Relative contraindications may be overlooked in the emergency situation.

* Relative contraindications may be overlooked in the true emergency situation, because it is more important to obtain an airway and avoid hypoxemia.

* Relative contraindications may be overlooked in the true emergency situation, because it is more important to obtain an airway and avoid hypoxemia.

* Based on personal preference, experience, the patient’s clinical condition.