Differential diagnosis phase 1: medical screening by the therapist

WILLIAM G. BOISSONNAULT, PT, DHSc, FAAOMPT, FAPTA and DARCY A. UMPHRED, PT, PhD, FAPTA

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Identify the difference between Differential Diagnosis Phase 1, medical screening, and Phase 2, diagnosis of impairments and functional limitations.

2. Analyze the concept of body system and subsystem screening.

3. Develop a mechanism for body system screening to be used with clients with preexisting neurological dysfunction.

4. Analyze the significance and importance of performing a medical screening for all clients who interact in a therapeutic environment with occupational or physical therapists.

5. Differentiate between direct causation of a clinical symptom as opposed to system causation of a clinical problem.

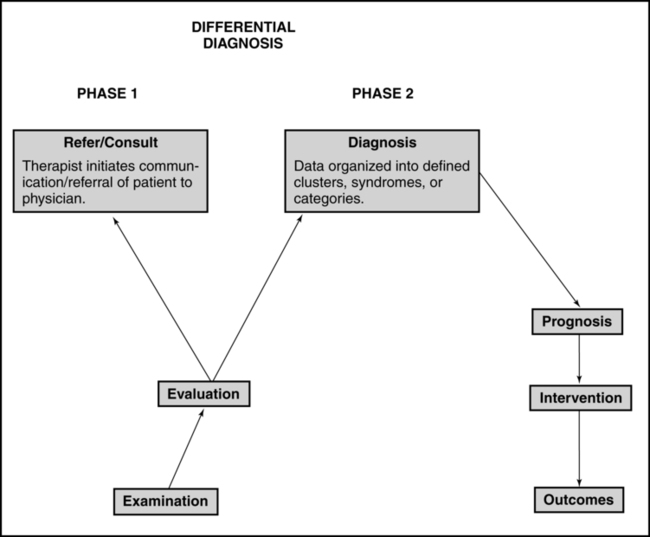

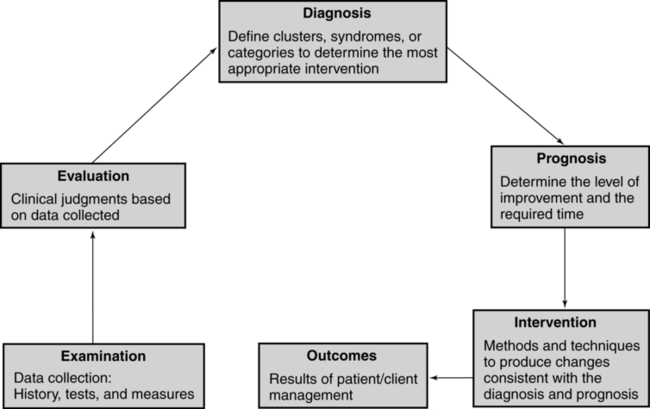

For the professions of physical and occupational therapy the concepts associated with and use of the term differential diagnosis are still evolving and under debate. A recent editorial describes diagnosis in physical therapy as complex and controversial, with diverse views existing.1 For physical therapists (PTs), the guiding premise is that the differential diagnostic process fits within the Patient/Client Management Model described in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice2 (Figure 7-1) and within The Guide to Occupational Therapy Practice.3 The therapist attempts to organize the history and physical examination (including tests and measures) findings into clusters, syndromes, or categories. There are certain clusters of findings that suggest the presence of disease or an adverse drug event and warrant communication with a physician. There are other symptoms and signs that are consistent with conditions that still fit into the older disablement framework. In the world today, the model of choice of all therapists is the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which moves away from the consequences of disease classification to a health focus classification. Thus a shift in how one looks at disease and its impact on health and wellness not only has changed the words used by therapists but also incorporates external societal limitations that our clients face.4 These changes do not affect the way a therapist should medically screen before formulating a clinical diagnoses based on movement dysfunction. These conditions are inherent in the interrelationships among impairments, functional or activity limitations, and participation in life and are appropriate for physical or occupational therapy interventions.2,3,5,6

Patient/client management model. (Adapted from American Physical Therapy Association: Guide to physical therapist practice. Phys Ther 81:43, 2001, with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association.)

Patient/client management model. (Adapted from American Physical Therapy Association: Guide to physical therapist practice. Phys Ther 81:43, 2001, with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association.)The process of differentiating the cluster of findings that warrant communication with a physician regarding concerns about a patient’s health status compared with those that do not will be called Differential Diagnosis Phase 1.7 In this scenario a physician will ultimately diagnose the patient’s illness, but the PT’s and occupational therapist’s (OT’s) examination findings and subsequent patient referral contribute to the diagnosis being generated. For many of these illnesses, the use of advanced imaging, laboratory testing, and/or tissue biopsy is necessary for the diagnosis to be made.8 Numerous examples exist in Physical Therapy Journal and Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy of published case reports and case series describing such action taken by PTs.

If the decision is reached that the symptoms and signs do fall within the scope of practice of PTs and OTs, a second level of differential diagnosis occurs. Now the therapist attempts to categorize the examination findings into the specific diagnostic categories that will specifically guide the choice of treatment interventions and the development of a prognosis. This second level of diagnosis is called Differential Diagnosis Phase 27 and is the focus of Chapters 8 and 9. Figure 7-2 illustrates where Differential Diagnosis Phase 1 and Phase 2 fit into the Patient/Client Management Model.

Differential diagnosis phase 1: medical screening

The Guide to Physical Therapy Practice2,9 and The Guide to Occupational Therapy Practice3 clearly describe the therapists’ responsibility to refer patients/clients with health concerns to other practitioners. The emphasis of the following discussion is detecting clinical manifestations that suggest the specific need for physician intervention. Typically the initial warning signs associated with these scenarios include a recent onset or exacerbation of symptoms such as pain, weakness, numbness, dizziness, falls, confusion, and so on—common complaints of patients with neurological disorders. Therapists may also detect symptoms or signs unrelated to the primary medical neurological condition but that could be related to an existing comorbidity or a medication side effect. In addition, a general health and wellness screen may reveal a need for a psychological, dermatological, or other nonneurological medical consultation.

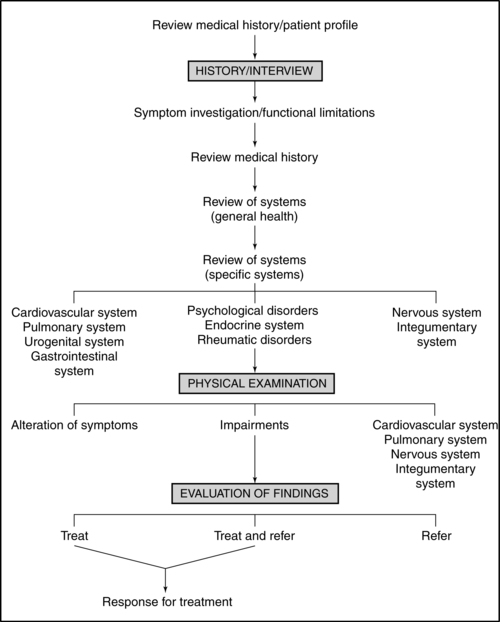

The purpose of the therapist’s medical screening is to (1) identify existing medical conditions, (2) identify symptoms and signs suggesting that an existing medical condition may be worsening, (3) identify neurological manifestations that suggest an acute or life-threatening crisis, and (4) identify symptoms and signs suggestive of the presence of an occult disorder or medication side effect. This medical screening has always taken place within the clinical framework of PTs’ and OTs’ practices, but as practitioners become more autonomous, this screening must become more comprehensive, requiring tools and documented evaluation results. Figure 7-3 is an example of an examination scheme leading to the decision to treat the patient, to treat and refer the patient, or to refer the patient. Phase 2 may also include the decision to refer the patient to another practitioner (e.g., dietician, social worker, clinical psychologist) for services augmenting the therapy or to social programs such as wellness clinics that will encourage the patient to participate in movement activities even though he may need individualized therapeutic intervention. The following material focuses on the components of this scheme most directly related to the medical screening process leading to a patient referral.

Identifying patients’ health risk factors and previous conditions

Of these, a personal history of a current or recent medical condition, current medication use, and a positive family history (e.g., mother and aunt with a history of breast cancer, father diagnosed with prostate cancer at the age of 58 years) are the most relevant risk factors for the potential presence of an occult condition. For example, the history of a previous episode of depression significantly increases the risk of a second episode compared with the risk that someone who has never had an episode of depression will have his or her first such episode.10 The greater the number of existing risk factors, the more vigilant the therapist should be for the presence of warning signs suggestive of disease and the more extensive the other medical screening components will need to be. Those increased risk factors, whether within one system or multiple systems, can lead to clinical behaviors that are the summation of the systems problems and their interactions that affect movement. Physicians should be able to depend on the therapist to recognize these interactive symptoms and refer the patient back to either the referring physician or to another specialist.

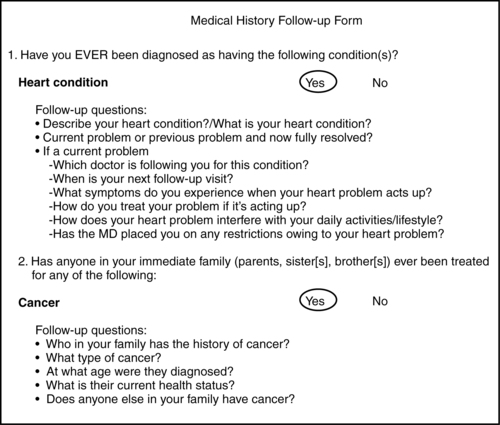

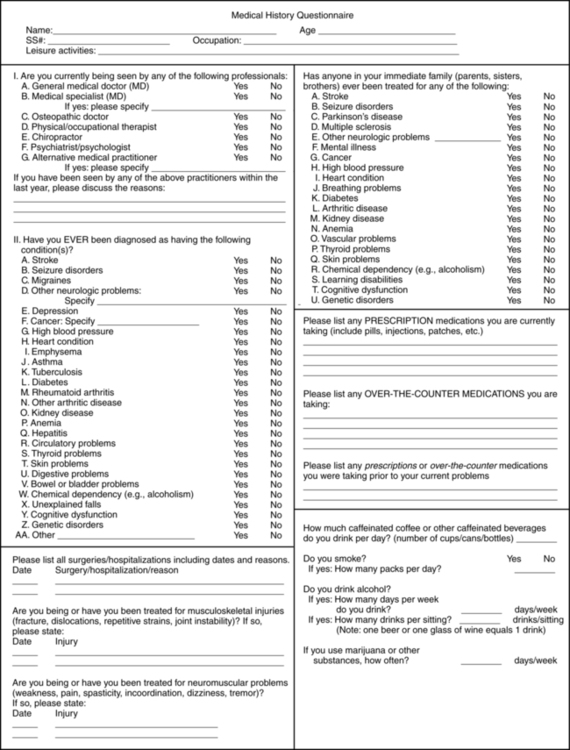

There are different methods to collect this medical history and patient profile information, including a review of the medical record and use of a self-administered questionnaire, depending on the practice setting and patient population. Figure 7-4 is an example of a self-administered questionnaire that could be completed by the adult patient, a family member, or a caregiver. As noted in Figure 7-3, a quick scanning review of this information should occur, if possible, before the patient interview is begun. The therapist will have a head start in organizing the history and physical examination, knowing what to prioritize and at least initially what parts of the examination can be deemphasized. The utility and accuracy of a self-administered questionnaire in patient populations germane to therapists’ practice, similar to the one illustrated in Figure 7-4, have been described, with the conclusion that such a tool can be a valuable adjunct to the oral patient interview.11

Self-administered questionnaire to collect medical history information. (Modified from Boissonnault WG, Koopmeiners MB: Medical history profile: orthopaedic physical therapy outpatients. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 20:2–10, 1994, with permission of the Orthopaedic and Sports Sections of the American Physical Therapy Association.)

Self-administered questionnaire to collect medical history information. (Modified from Boissonnault WG, Koopmeiners MB: Medical history profile: orthopaedic physical therapy outpatients. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 20:2–10, 1994, with permission of the Orthopaedic and Sports Sections of the American Physical Therapy Association.)Affirmative answers to previous or current illness questions should direct the therapist to consider what the potential impact may be on the patient’s symptoms, choice of examination and treatment techniques, rehabilitation potential, and risk for additional illness. For example, the presence of existing chronic kidney disease (e.g., renal failure) should alert the therapist to numerous potential complications including patient fatigue, weakness, and impaired concentration, all of which could interfere with rehabilitation efforts. Chronic renal failure is also marked by paresthesia and muscle weakness, which could mistakenly be associated with other neurological conditions. Renal osteodystrophy is yet another complication associated with chronic renal failure. The concern of compromised bone density should direct the therapist to use techniques that carry a reduced risk of skeletal injury. A series of follow-up questions for the affirmative answers will assist the therapist in determining the relevance (if any) of each item (see Figure 7-5 for examples of follow-up questions for selected information categories).

Symptomatic investigation of functional restriction

The chief presenting symptoms or functional restriction typically provides the reason for therapy services being sought and can provide the initial warning sign(s) of potential medical issues needing to be addressed. Despite pain not typically being the chief complaint of many patients with primary neurological conditions, a relatively mild pain is often the initial complaint associated with a serious pathological condition; a dull diffuse ache is often the initial presenting complaint associated with tumors of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system.12 This relatively minor complaint can easily be overlooked by therapists working with patients who have neurological involvement and signs and symptoms (e.g., weakness, numbness) that are much more debilitating and cause more functional limitations than the pain complaints do. Although investigating pain complaints may not be the initial priority for these therapists, at a later visit such questioning is very important, especially if it continues, increases in intensity, shifts, or enlarges its region with no causation. Effective medical screening involves the interpretation of a patient’s description of symptoms, functional limitations, and the corresponding physical examination findings. Descriptions of symptoms associated with neuromusculoskeletal impairments (loss or abnormality of physiological, psychological, or anatomical structure or function) generally reveal a fairly consistent and predictable pattern of onset and change over a defined period of time. In addition, the neurological and MSK impairments noted during the physical examination should match with the functional limitations described by the patient or the caregiver. If these expectations are not met, it does not necessarily mean the patient has cancer or an infection, but doubt should be raised on the therapist’s part whether therapy is indicated.

Location of symptoms

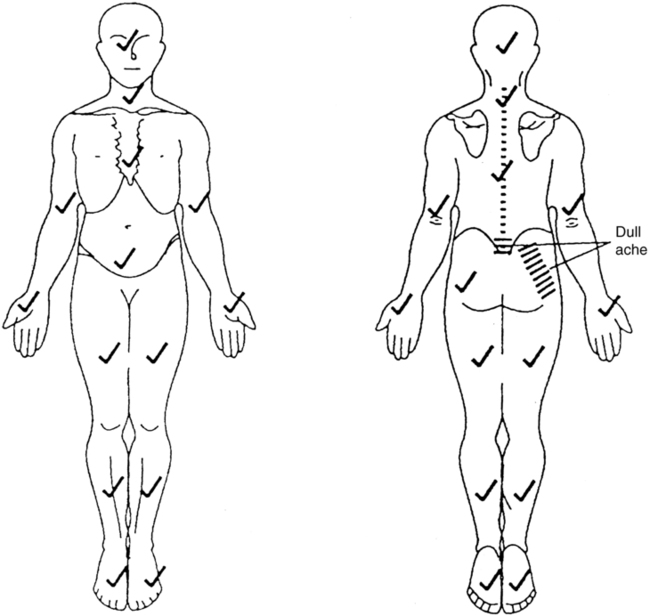

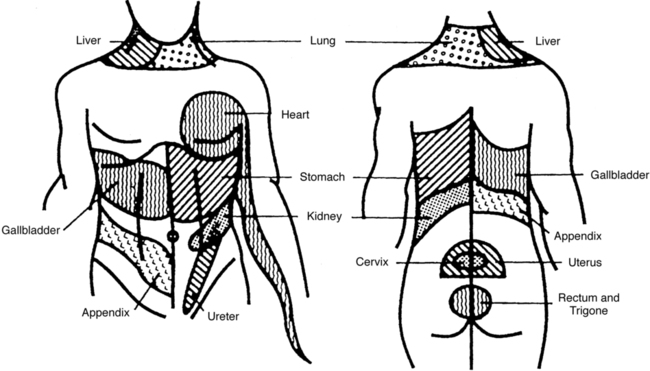

A body diagram can be a valuable tool to document the location of symptoms expressed verbally or nonverbally by patients with identified neurological deficits. Besides pain and altered sensation, patterns of abnormal tone, asymmetrical posturing, and areas of weakness can also be noted on the body diagram (Figure 7-6). Numerous body structures are potential pain generators, including visceral structures. Figure 7-7 and Table 7-1 illustrate local and referred pain patterns from various visceral organs. Although the presented pain patterns illustrate those most commonly noted, clinicians should be aware of other potential patterns. For example, ischemic heart disease—the complaint of left chest wall and left upper extremity pain, pressure, or tightness—is not the classic presentation for women and many of the elderly. Besides what is noted in Figure 7-7 and Table 7-1, pain from the heart can also be experienced in the right shoulder or biceps, jaw and tooth, epigastric, and interscapular regions.13,13a

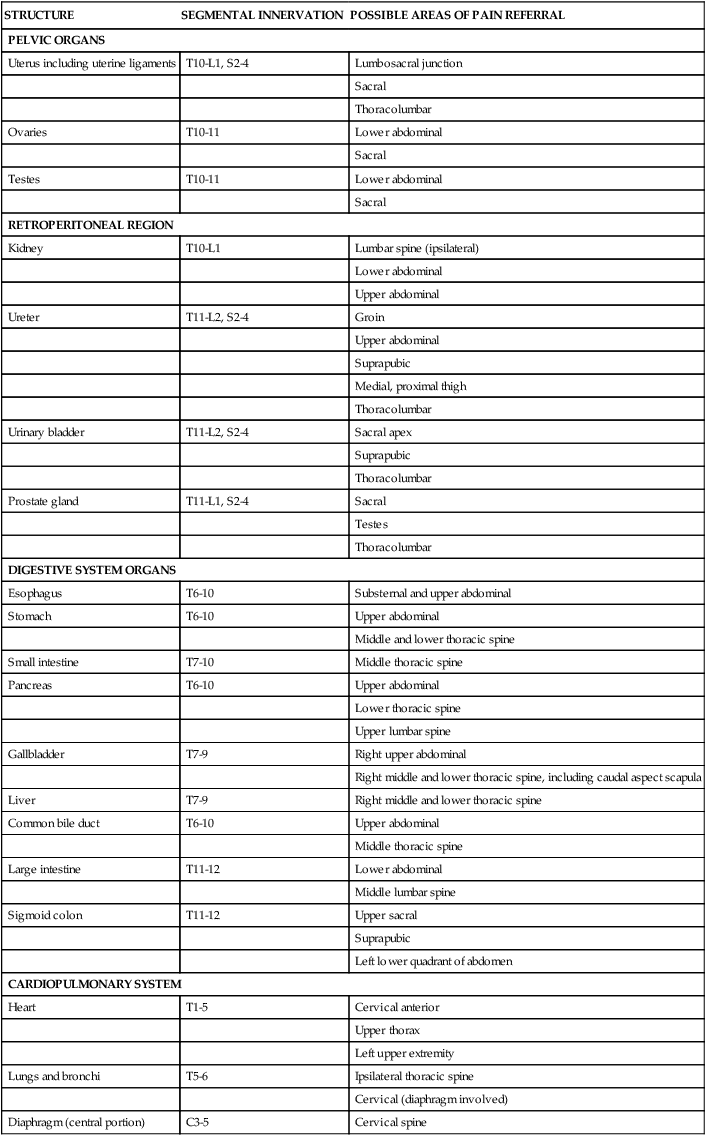

TABLE 7-1

| STRUCTURE | SEGMENTAL INNERVATION | POSSIBLE AREAS OF PAIN REFERRAL |

| PELVIC ORGANS | ||

| Uterus including uterine ligaments | T10-L1, S2-4 | Lumbosacral junction |

| Sacral | ||

| Thoracolumbar | ||

| Ovaries | T10-11 | Lower abdominal |

| Sacral | ||

| Testes | T10-11 | Lower abdominal |

| Sacral | ||

| RETROPERITONEAL REGION | ||

| Kidney | T10-L1 | Lumbar spine (ipsilateral) |

| Lower abdominal | ||

| Upper abdominal | ||

| Ureter | T11-L2, S2-4 | Groin |

| Upper abdominal | ||

| Suprapubic | ||

| Medial, proximal thigh | ||

| Thoracolumbar | ||

| Urinary bladder | T11-L2, S2-4 | Sacral apex |

| Suprapubic | ||

| Thoracolumbar | ||

| Prostate gland | T11-L1, S2-4 | Sacral |

| Testes | ||

| Thoracolumbar | ||

| DIGESTIVE SYSTEM ORGANS | ||

| Esophagus | T6-10 | Substernal and upper abdominal |

| Stomach | T6-10 | Upper abdominal |

| Middle and lower thoracic spine | ||

| Small intestine | T7-10 | Middle thoracic spine |

| Pancreas | T6-10 | Upper abdominal |

| Lower thoracic spine | ||

| Upper lumbar spine | ||

| Gallbladder | T7-9 | Right upper abdominal |

| Right middle and lower thoracic spine, including caudal aspect scapula | ||

| Liver | T7-9 | Right middle and lower thoracic spine |

| Common bile duct | T6-10 | Upper abdominal |

| Middle thoracic spine | ||

| Large intestine | T11-12 | Lower abdominal |

| Middle lumbar spine | ||

| Sigmoid colon | T11-12 | Upper sacral |

| Suprapubic | ||

| Left lower quadrant of abdomen | ||

| CARDIOPULMONARY SYSTEM | ||

| Heart | T1-5 | Cervical anterior |

| Upper thorax | ||

| Left upper extremity | ||

| Lungs and bronchi | T5-6 | Ipsilateral thoracic spine |

| Cervical (diaphragm involved) | ||

| Diaphragm (central portion) | C3-5 | Cervical spine |

Modified from Boissonnault WG, Bass C: Pathological origins of trunk and neck pain, I. Pelvic and abdominal visceral disorders. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 12:192–207, 1990, with permission of the Orthopaedic and Sports Sections of the American Physical Therapy Association.

Body diagram illustrating symptom location. Body areas with no known symptoms or abnormalities are marked with a checkmark. (From Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice—screening for medical disease, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

Body diagram illustrating symptom location. Body areas with no known symptoms or abnormalities are marked with a checkmark. (From Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice—screening for medical disease, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

Possible local and referred pain patterns of visceral structures. (From Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice—screening for medical disease, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

Possible local and referred pain patterns of visceral structures. (From Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice—screening for medical disease, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)Because there is so much overlap between pain locations associated with visceral disease and neuromusculoskeletal conditions, the results obtained in and of themselves have minimal use in differentiating MSK from non-MSK conditions. Being familiar with the visceral pain patterns will be extremely important, however, when deciding which body systems to screen during the review of systems. Besides noting where symptoms are located, it is equally important to document areas of no complaints (see Figure 7-6). Once the patient has reported symptoms (e.g., low back and right buttock aching, see Figure 7-6), therapists should clarify. Screening to eliminate the possibility of symptoms being present down the back and up the front of the legs; in the pelvis, stomach, chest, neck and face areas; or between the shoulder blades and in the arms is critical. If there is one body area so involved that all the patient’s and practitioner’s attention is focused on it, a relatively mild but potentially serious symptom may be overlooked elsewhere. Placing a checkmark over each body region devoid of symptoms or other abnormal findings is one way to document such information and record change over time.

Symptom pattern

Aspects of the patient’s chief complaint other than symptom location are very relevant to the process of differential diagnosis, in particular a description of how and when the symptoms changed over a defined period of time. Complaints of pain, paresthesia, and numbness associated with primary MSK conditions typically change in a consistent manner over a 24-hour period. The patient will report that the symptom intensity increases with the assumption of specific postures such as left side lying or sitting or with specific activities such as walking, driving, or 2 hours of computer work. Conversely, patients typically can relate paresthesia or pain relief with avoiding certain postures or activities, the assumption of certain postures, wearing an arm sling, and so on. Night pain investigation also falls under this subcategory of patient data. Pain that wakes an individual from sleep and for which changing positions in bed does not provide relief is more concerning than if the pain is positionally related. If the pattern of symptom aggravation and alleviation is that there is no consistent pattern, such as pain that comes and goes independently of the patient’s posture, activities, or time of day; night pain is the patient’s most intense pain; or paresthesia or pain moves from one body region to another inconsistently with common pain referral patterns or identified medical conditions, then the therapist should start thinking whether physical or occupational therapy is what the patient truly needs.14

History of symptoms

The therapist must also scrutinize the patient’s report of the onset of the symptoms. Pain and paresthesia or numbness associated with neuromusculoskeletal impairments typically can be related to trauma, either on a macro or a micro level, or to a medical event such as a cerebrovascular accident. More often than not it is repetitive overuse or cumulative trauma that leads to tissue breakdown and inflammation (see Chapter 18). Patients with neurological impairments resulting in postural abnormalities and abnormal movement patterns are at risk for such conditions. If a patient’s symptoms are truly insidious, meaning not related to macro or micro trauma, or there has not been a significant change in activity level that reasonably accounts for the complaints, the therapist should again be concerned about the source of the symptoms. A worsening of symptoms (e.g., numbness, weakness, spasticity, swelling) associated with an existing medical condition should be investigated by the therapist with the same scrutiny. The therapist always needs to ask, “Is there a reasonable explanation for the worsening?” An increase in the intensity of the complaints or the involvement of additional body regions could signal a progression of the disease.

Review of body systems

By design, review of systems screening allows the therapist to detect symptoms secondary (and maybe unrelated) to the reason therapy has been initiated.15 The review of systems allows for a general screening of body systems for symptoms suggesting the presence of an adverse drug reaction, occult disease, or worsening of an existing medical condition. Suspicions of any of these scenarios would warrant communication with a physician. Checklists of symptoms and signs for each body system can be used by the PT or OT during the patient interview (Box 7-1). To keep the checklists manageable in length, the therapist should investigate presenting complaints and symptoms and the patient’s medical history before the review of systems, as noted in Figure 7-3. For example, on review of the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular system checklist items associated with heart conditions in Box 7-1, important items appear to be omitted, such as chest pain, claudication, a history of heart problems, hypertension, high cholesterol levels, and circulatory problems. If symptoms have already been investigated by use of a body diagram, the therapist would already know whether the patient has chest pain. If symptom change (aggravation or alleviation) over a 24-hour period has already been investigated, the therapist would know whether claudication is an issue. Finally, if the patient’s medical history has already been discussed, the therapist would know whether heart problems, hypertension, or circulatory problems existed.13a

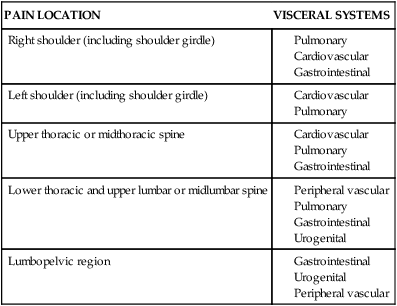

All of the checklists in Box 7-1 need not be used for every patient. The location of symptoms will direct the therapist in deciding which checklists should be included in the initial examination. Figure 7-7 and Table 7-1 can be used to link pain location with visceral systems that could be the source of the complaints. Table 7-2 provides a summary of potential pain locations and diseases of the pulmonary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and urogenital systems. Other symptom characteristics can also alert the therapist to the possible involvement of the endocrine, nervous, and psychological systems. Symptoms, including pain and paresthesias that come and go irrespective of posture, activity, or time of day and that appear to move among the various body regions, can be associated with these systems as well as the visceral systems. In addition to the identification of the location and characteristics of symptoms, a patient’s medical history will also help the therapist decide which systems to screen. A positive medical history, such as a heart problem, would direct the therapist to investigate the patient’s condition, including possible use of the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular checklist as well as the questions listed in Figure 7-5. The therapist also needs to be aware of the medications taken by the patient to medically manage these pathological conditions. Similarly, therapists need to be able to analyze how the drugs potentially affect functional movements and functional loss. Often, that means a therapist must have a working professional relationship with a clinical pharmacist (see Chapter 36). Use of a general health checklist (Box 7-2) can assist the therapist in prioritizing the inclusion of the checklists in the systems review checklists box during the initial visit. The symptoms noted in this checklist can be associated with disease of most of the body’s systems, as well as with systemic disease and adverse drug events.

TABLE 7-2

LINKING PAIN PATTERNS AND VISCERAL SYSTEMS

| PAIN LOCATION | VISCERAL SYSTEMS |

| Right shoulder (including shoulder girdle) |

Musculoskeletal system

Box 7-3 provides the checklist for the MSK system. In addition, as with all other body systems, the general health checklist also provides a level of screening for conditions of the MSK system such as infections, metastatic cancers, and rheumatic disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis). Identifying patient risk factors for these conditions is a key for recognizing when to be suspicious. For example, those at highest risk for MSK cancers are those (1) over the age of 50 years and under 20 years, (2) having a previous history of cancer (e.g., breast, lung, prostate, thyroid, and kidney—the most common cancers to metastasize to the axial skeleton), (3) having a positive family history of cancer, and (4) having had exposure to environmental toxins. Those individuals at highest risk for MSK infections report or demonstrate (1) current or recent infection (e.g., urinary tract, tooth abscess, skin infection), (2) history of diabetes with use of large doses of steroids or immunosuppressive drugs, (3) elderly age, and (4) spinal cord injury with complete motor and sensory loss.16 Last, the primary risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis include (1) female sex, (2) age (peak) 30 to 40 years, and (3) positive family history.17

The other category of MSK conditions for which therapists need to be vigilant is fractures. The pain and deformity associated with most sudden-impact, traumatic fractures make for an obvious presentation. However, trauma sufficient to cause a fracture may not be so obvious in a patient with decreased bone density. Lifting a gallon of milk, experiencing a mild slip or bump, or trying to open a window that is stuck may be sufficient to cause a fracture in a patient with a history of chronic renal failure, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperparathyroidism, gastrointestinal malabsorption syndrome, and long-term corticosteroid, heparin, anticonvulsant, and cytotoxic medication use. The most common locations for such fractures include vertebral bodies, the neck of the femur, and the radius. Observation of posture and body position may provide a clue that something may have changed structurally. For example, with vertebral compression fractures the thoracic kyphotic curve may be accentuated, accompanied by a very pronounced apex of the curve that was not present before. With femoral neck fracture the lower extremity is often positioned in external rotation and appears shortened compared with its counterpart.18

Integumentary system

Screening of the integumentary system is not typically based on the presence or absence of pain, paresthesia, or numbness. As with the nervous system, some degree of screening of the integumentary system occurs with every patient regardless of the presenting diagnosis. Skin cancer has the highest incidence of all the cancers,19 and therapists generally see a number of exposed body areas during the postural assessment and regional examination that make up the physical examination. In fact, as noted in Figure 7-3, screening the skin begins during the patient interview. During the interview the therapist can be looking at areas of exposed skin such as the face, neck, arms, and feet. As with screening of the other body systems, the therapist’s goal is not to identify a melanoma or differentiate squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma but simply to identify skin lesions with atypical presentations. Once the patient has been referred to the physician, disease will be ruled out or diagnosed. Box 7-4 can be used to assess any mole or other skin marking. The items noted are atypical for a benign lesion, more suggestive of a pathological condition.20 Selected items from Box 7-4 have been highlighted, resulting in an acronym—A (asymmetry), B (borders), C (color), D (diameter), and E (evolving)—that has been used to educate the public for self-screening.21 If the therapist notes any of these findings and the patient reports a recent change in the size, color, or shape of the lesion and that a physician has not looked at the lesion, a referral would be warranted.

Besides skin lesions, abnormal general skin color can be a manifestation of a number of conditions. Table 7-3 summarizes abnormal skin color changes. Occasionally, some of the most obvious abnormalities are the most difficult to note when one is so focused on items more directly related to therapeutic intervention.

TABLE 7-3

ABNORMAL COLOR CHANGES OF THE SKIN

| COLOR CHANGE | PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGE | COMMON CAUSES |

| White, pale (pallor) | Absence of pigment or pigment changes | Albinism, lack of sunlight |

| Blood abnormality | Anemia, lead poisoning | |

| Temporary interruption or diversion of blood flow | Vasospasm, syncope, stress, internal bleeding | |

| Internal disease | Chronic gastrointestinal disease, cancer, parasitic disease, tuberculosis | |

| Blue (cyanosis) | Decreased oxygen in blood (deoxyhemoglobin) | Methemoglobinemia (oxidation of hemoglobin), high blood iron level, cold exposure, vasomotor instability, cerebrospinal disease |

| Yellow | Jaundice, excess bilirubin in blood, excess bile | Liver disease, gallstone blockage of bile duct, hepatitis pigment (conjunctivae are also yellow) |

| High levels of carotene in blood (carotenemia) | Ingestion of food high in carotene and vitamin A | |

| Gray | High level of metals in body | Increased iron, bronze-gray; increased silver, blue-gray |

| Brown (hyperpigmentation) | Disturbances of adrenocortical hormones | Adrenal pituitary |

| Addison disease |

From Shapiro C, Skopit S: Screening for skin disorders. In Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice—screening for medical disease, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.

Nervous system

As with the integumentary system, the nervous system is screened to a degree for all patients. The systems review checklists in Box 7-1 include items that provide a very gross, general screening of the nervous system. The therapist should be vigilant for the presence of any of these items in all patients during the initial and subsequent visits. For patients with preexisting findings from this checklist, the therapist must be vigilant for a worsening of the observed abnormalities. Covering the items in the nervous system checklist should add little time to the therapist’s initial examination. Assessing for facial asymmetries and tremors can take place during the interview. Observing balance, movement patterns, and muscle atrophy can occur while watching the patient ambulate into the examination area, during the interview, and as the patient changes positions during the physical examination. Last, impaired mentation may become apparent during the interview or the physical examination as the patient struggles to appropriately answer questions or follow directions. Case Studies 7-1 and 7-2 illustrate the importance of this general screening.

Depression.

Depression is a commonly encountered psychological disorder that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.10,22–24 The systems review checklists in Box 7-1 contain items the therapist can use to help make the decision to refer a patient for consultation. If the patient has suicide ideation, the physician should be contacted before the patient leaves the clinic. For the first eight items on the depression checklist, concern should be raised when the therapist detects four or five of the items present daily for a minimum of 2 weeks and resulting in the patient having difficulty functioning at home, work, or school, socially, or in rehabilitation. Of the four or five items, one of them should be depressed or irritable affect or apathy. An exception to the 2-week time frame is during periods of bereavement. When people are faced with a significant loss, it is not uncommon for them to experience a number of the checklist items as they work through the grieving process (refer to Chapter 6).10 It is reasonable for these people to experience these symptoms for up to 2 months. A neurological event such as a cerebrovascular accident could easily trigger a major clinical depressive disorder, and the depression could significantly impede rehabilitation progress. The therapist may be in a position to facilitate a psychological consultation.

Considering that approximately 15% of people with true major clinical depression commit suicide,10 therapists need to be vigilant for warning signs that the patient may be considering this action. See the suicide screening shown in Box 7-5 for a list of warning signs. Once the patient acknowledges suicidal ideation, follow-up questions would be appropriate to investigate the patient’s plan and how readily available the resources are regarding the reported method of attempt. This is all-important information to be reported when the therapist contacts the physician. Therapists should be very familiar with their facility’s “suicide protocol or procedure” in terms of what information should be collected from the patient and who should be contacted.

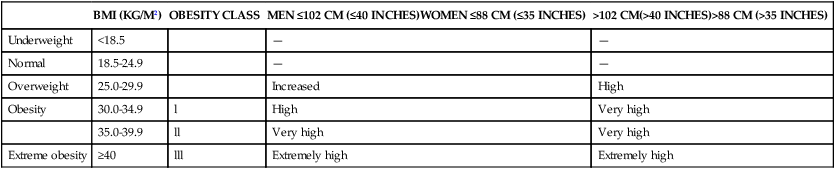

Physical examination

The Guide to Physical Therapy Practice describes the systems review, in part, as a brief or limited examination of the anatomical and physiological status of the cardiovascular and pulmonary, integumentary, MSK, and neuromuscular systems.1 For the purposes of this chapter the discussion will focus on assessment of height and weight and assessing heart rate and blood pressure. Being overweight or obese can significantly increase the risk of development of a number of serious conditions (Table 7-4). Using patient height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) can be a valuable measure to identify patients who may need a dietary consultation to prevent disease states or minimize morbidity associated with current illnesses. BMI is calculated by dividing body weight (in kilograms) by height (in meters). Table 7-4 provides a summary of disease risk associated with BMI and waist circumference.

TABLE 7-4

DISEASE RISK RELATIVE TO NORMAL WEIGHT AND WAIST CIRCUMFERENCE

| BMI (KG/M2) | OBESITY CLASS | MEN ≤102 CM (≤40 INCHES)WOMEN ≤88 CM (≤35 INCHES) | >102 CM(>40 INCHES)>88 CM (>35 INCHES) | |

| Underweight | <18.5 | — | — | |

| Normal | 18.5-24.9 | — | — | |

| Overweight | 25.0-29.9 | Increased | High | |

| Obesity | 30.0-34.9 | l | High | Very high |

| 35.0-39.9 | ll | Very high | Very high | |

| Extreme obesity | ≥40 | lll | Extremely high | Extremely high |

From the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/obesity/lose_wt/risk.htm/. Accessed July 20, 2011.

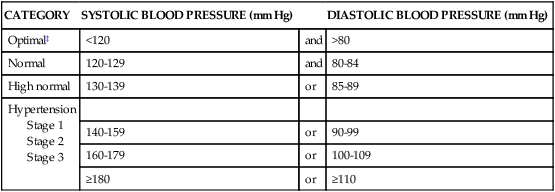

Resting blood pressure and pulse rate and rhythm are also important values to be routinely measured. See Table 7-5 for a summary of blood pressure values for adults. Table 7-6 presents normal resting pulse rate parameters for therapists to consider when examining a patient. A 30-second monitoring period after a 2- to 5-minute rest period is recommended to obtain baseline rate values.25 Resting blood pressure values can also provide important screening information. As with assessing pulse rate, resting blood pressure should be assessed after a 5-minute rest period. Variations from the normative values may lead therapists to additional assessment of the vascular system and the central autonomic nervous system and then to a patient referral.

TABLE 7-5

CLASSIFICATION OF BLOOD PRESSURE FOR ADULTS 18 YEARS OLD OR OLDER*†

| CATEGORY | SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE (mm Hg) | DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE (mm Hg) | |

| Optimal‡ | <120 | and | >80 |

| Normal | 120-129 | and | 80-84 |

| High normal | 130-139 | or | 85-89 |

| Hypertension Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 |

|||

| 140-159 | or | 90-99 | |

| 160-179 | or | 100-109 | |

| ≥180 | or | ≥110 |

*Not taking antihypertensive drugs and not acutely ill. When systolic and diastolic blood pressures fall into different categories, the high category should be selected to classify the individual’s blood pressure status. In addition to classifying stages of hypertension on the basis of average blood pressure levels, clinicians should specify presence or absence of target organ disease and additional risk factors. This specificity is important for risk classification and treatment.

†Based on the average of two or more readings taken at each of two or more visits after an initial screening.

‡Optimal blood pressure regarding cardiovascular risk is less than 120/80 mm Hg. However, unusually low readings should be evaluated for clinical significance.

From The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 23:275–285, 1994, and The Sixth Report of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, 1997.

TABLE 7-6

RESTING PULSE RATE IN BEATS PER MINUTE

| AVERAGE | LIMITS | |

| Norms | 120-160 | — |

| Fetal | 120 | 70-190 |

| Newborn | 120 | 80-160 |

| 1 year old | 110 | 80-130 |

| 2 years old | 100 | 80-120 |

| 4 years old | 100 | 75-115 |

| 6 years old | 90 | 70-110 |

| 8-10 years old | ||

| 12 years old | ||

| Female | 90 | 70-110 |

| Male | 85 | 65-105 |

| 14 years old | ||

| Female | 85 | 65-105 |

| Male | 80 | 60-100 |

| 16 years old | ||

| Female | 80 | 60-100 |

| Male | 75 | 55-95 |

| 18 years old | ||

| Female | 75 | 55-95 |

| Male | 70 | 50-90 |

| Well-conditioned athlete | 50-60 | 50-100 |

| Adult | — | 60-100 |

| Aging | — | 60-100 |

Modified from Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1992, WB Saunders.

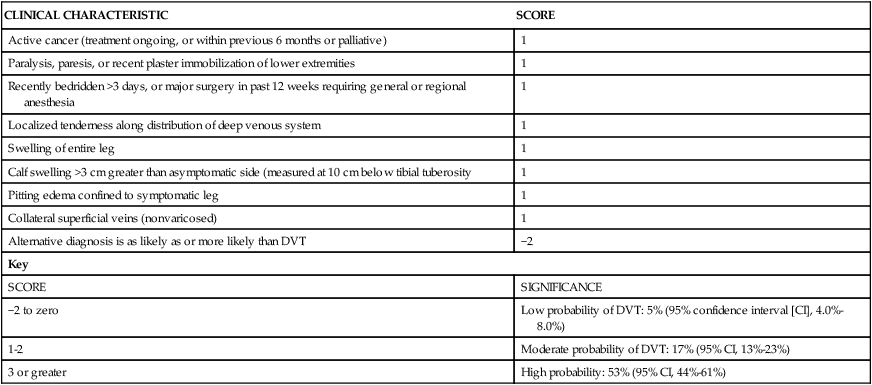

Examination summary

For many patients a single red flag finding does not warrant a referral, but a cluster of history and physical examination findings does increase disease probability to the point where a referral is indicated. Two examples that are germane to a number of individuals with neurological conditions are deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus (PE). DVT affects approximately 2 million individuals in the United States annually, making it the third most common cardiovascular disease.26 A sobering estimation is that approximately 50% of those with a DVT are asymptomatic in early stages.27 Clinicians are challenged to identify patients at greater risk for this condition who do not have the obvious signs and symptoms of calf pain, swelling, and redness. The following clinical decision rule has been validated in ambulatory patient populations (Table 7-7). Of note for the neurological population, a history of spinal cord injury does not appear in this rule even though it is considered a strong risk factor for DVT. The authors assume there were very few patients with spinal cord injury in the validation research.

TABLE 7-7

CLINICAL DECISION RULE FOR DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS (DVT)

| CLINICAL CHARACTERISTIC | SCORE | |

| Active cancer (treatment ongoing, or within previous 6 months or palliative) | 1 | |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of lower extremities | 1 | |

| Recently bedridden >3 days, or major surgery in past 12 weeks requiring general or regional anesthesia | 1 | |

| Localized tenderness along distribution of deep venous system | 1 | |

| Swelling of entire leg | 1 | |

| Calf swelling >3 cm greater than asymptomatic side (measured at 10 cm below tibial tuberosity | 1 | |

| Pitting edema confined to symptomatic leg | 1 | |

| Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricosed) | 1 | |

| Alternative diagnosis is as likely as or more likely than DVT | −2 | |

| Key | ||

| SCORE | SIGNIFICANCE | |

| −2 to zero | Low probability of DVT: 5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.0%-8.0%) | |

| 1-2 | Moderate probability of DVT: 17% (95% CI, 13%-23%) | |

| 3 or greater | High probability: 53% (95% CI, 44%-61%) |

From Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al: Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management, Lancet 350(9094; Dec 20-27):1795-1798, 1997.

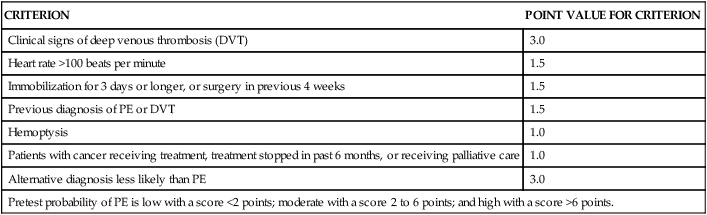

Similarly for PE, a clinical decision rule exists for screening (Table 7-8). PE is associated with high morbidity and mortality, highlighting the critical nature of timely detection. Hull describes PE as one of the “great masqueraders” of medicine because of the often nonspecific presenting symptoms and signs.28 Wells and colleagues estimate that 50% of PEs go undiagnosed.29

TABLE 7-8

“WELLS” CRITERIA FOR DETERMINING PROBABILITY OF PULMONARY EMBOLISM (PE)

| CRITERION | POINT VALUE FOR CRITERION |

| Clinical signs of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) | 3.0 |

| Heart rate >100 beats per minute | 1.5 |

| Immobilization for 3 days or longer, or surgery in previous 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Previous diagnosis of PE or DVT | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Patients with cancer receiving treatment, treatment stopped in past 6 months, or receiving palliative care | 1.0 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3.0 |

| Pretest probability of PE is low with a score <2 points; moderate with a score 2 to 6 points; and high with a score >6 points. |

Data from Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al: Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and a d-dimer. Ann Intern Med 135:98–107, 2001.

Conclusion

The responsibilities of the PT and OT related to screening for symptoms and signs that indicate the involvement of another health care practitioner are clearly stated in the Guide to Physical Therapy Practice2 and The Guide to Occupational Therapy Practice.3 The process associated with Differential Diagnosis Phase 1 allows for the appropriate medical screening yet keeps therapists within their scope of practice. The therapist simply communicates to the physician the list of clinical findings. The physician will determine whether new or additional medical tests are needed to rule out or diagnose specific diseases. Facilitating the timely referral of patients to physicians is an important role for therapists working within a collaborative medical model. It is this model that best serves the needs of our patients. For additional information related to the medical screening process, the readers are directed to four other textbooks.25,30–32