Differential diagnosis of radiolucent lesions of the jaws

Introduction

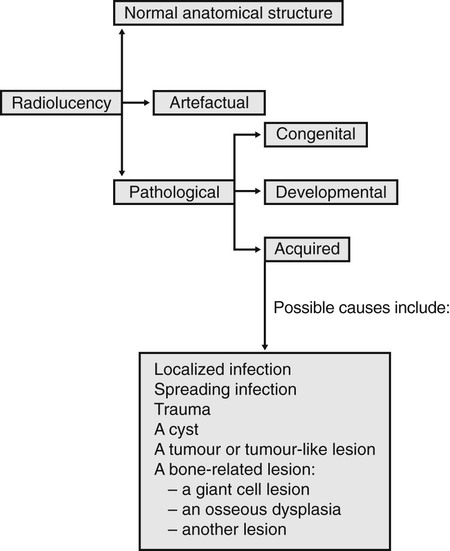

This chapter is designed to simplify the process of arriving at a radiological differential diagnosis when confronted with a radiolucency of unknown cause on a plain radiograph. This process requires clinicians to follow a methodical step-by-step approach and to know the typical features of the various possibilities. Such a step-by-step guide is suggested and summarized in Fig. 26.1. Although most lesions are still detected using plain radiographs, this process can be greatly facilitated in many cases if advanced imaging modalities, described in Chapters 16 and 18, such as computed tomography (CT), cone beam CT or magnetic resonance (MR), are available.

Step-by-step guide

Step IV

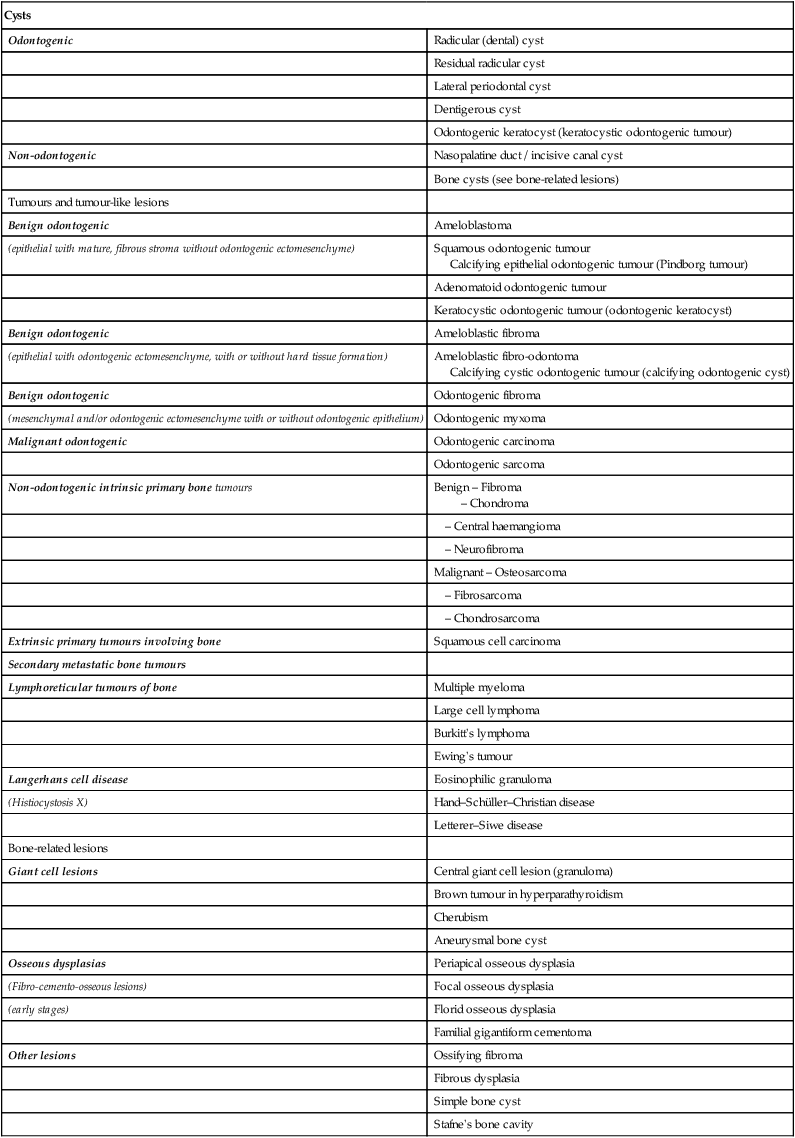

Consider the classification and subdivision of cysts and other similar radiolucencies within each of the other main disease categories, as shown in Table 26.1. This resultant list includes most of the more likely diagnostic possibilities for the unknown radiolucent lesion.

Table 26.1

| Cysts | |

| Odontogenic | Radicular (dental) cyst |

| Residual radicular cyst | |

| Lateral periodontal cyst | |

| Dentigerous cyst | |

| Odontogenic keratocyst (keratocystic odontogenic tumour) | |

| Non-odontogenic | Nasopalatine duct / incisive canal cyst |

| Bone cysts (see bone-related lesions) | |

| Tumours and tumour-like lesions | |

| Benign odontogenic | Ameloblastoma |

| (epithelial with mature, fibrous stroma without odontogenic ectomesenchyme) | Squamous odontogenic tumour Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour (Pindborg tumour) |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour | |

| Keratocystic odontogenic tumour (odontogenic keratocyst) | |

| Benign odontogenic | Ameloblastic fibroma |

| (epithelial with odontogenic ectomesenchyme, with or without hard tissue formation) | Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour (calcifying odontogenic cyst) |

| Benign odontogenic | Odontogenic fibroma |

| (mesenchymal and/or odontogenic ectomesenchyme with or without odontogenic epithelium) | Odontogenic myxoma |

| Malignant odontogenic | Odontogenic carcinoma |

| Odontogenic sarcoma | |

| Non-odontogenic intrinsic primary bone tumours | Benign – Fibroma – Chondroma |

| – Central haemangioma | |

| – Neurofibroma | |

| Malignant – Osteosarcoma | |

| – Fibrosarcoma | |

| – Chondrosarcoma | |

| Extrinsic primary tumours involving bone | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Secondary metastatic bone tumours | |

| Lymphoreticular tumours of bone | Multiple myeloma |

| Large cell lymphoma | |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | |

| Ewing’s tumour | |

| Langerhans cell disease | Eosinophilic granuloma |

| (Histiocystosis X) | Hand–Schüller–Christian disease |

| Letterer–Siwe disease | |

| Bone-related lesions | |

| Giant cell lesions | Central giant cell lesion (granuloma) |

| Brown tumour in hyperparathyroidism | |

| Cherubism | |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | |

| Osseous dysplasias | Periapical osseous dysplasia |

| (Fibro-cemento-osseous lesions) | Focal osseous dysplasia |

| (early stages) | Florid osseous dysplasia |

| Familial gigantiform cementoma | |

| Other lesions | Ossifying fibroma |

| Fibrous dysplasia | |

| Simple bone cyst | |

| Stafne’s bone cavity |

Step V

Infection is described elsewhere (apical, Ch. 21, spreading, Ch. 28) and trauma is described in Chapter 29. The rest of this chapter is devoted principally to differentiating between the different cysts – the most common of the remaining categories – and the other lesions that often present as very similar radiolucencies.

Typical radiographic features of cysts

Inflammatory odontogenic cysts

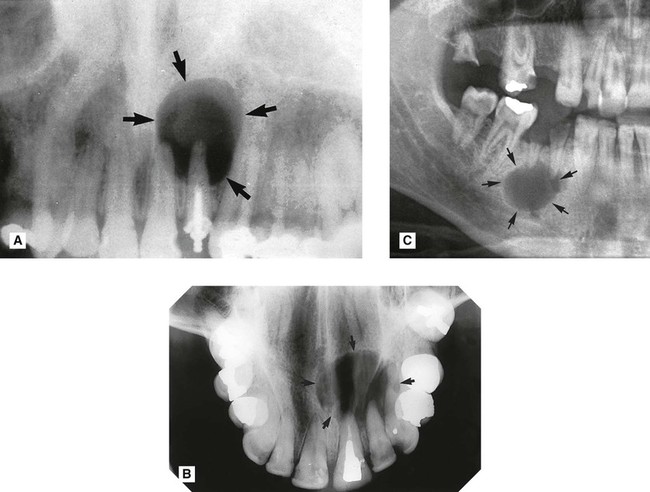

Radicular (dental) cyst (Fig. 26.2)

• Age: Usually adults, 20–50 year-olds.

• Frequency: Most common of all jaw cysts (about 70%).

• Site: Apex of any non-vital tooth, particularly upper lateral incisors.

• Size: 1.5–3 cm in diameter (if smaller the radiographic distinction between cyst and granuloma cannot usually be made).

— Well corticated if long-standing (unless infected) and continuous with the lamina dura of the associated tooth.

Note: The term buccal bifurcation cyst is used to describe an inflammatory odontogenic cyst that develops on the side of a molar tooth in relation to a buccal enamel spur or pearl.

Developmental odontogenic cysts

Lateral periodontal cyst (Fig. 26.4)

• Age: Adults over 30 years old.

• Site: Lateral surface of the roots of vital teeth in the lower canine/premolar region or upper lateral incisor region.

• Size: Small, less than 1 cm in diameter.

• Shape: —Unilocular, very occasionally multilocular

• Radiodensity: Uniformly radiolucent.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth displaced if cyst becomes large, rarely resorbed

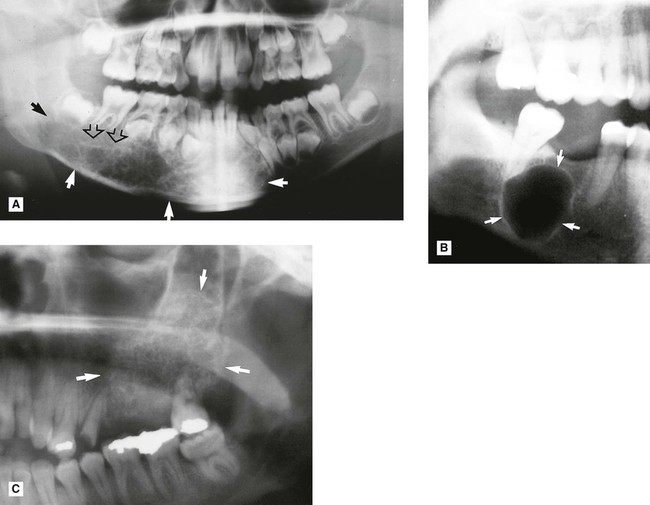

Dentigerous (follicular) cyst (Fig. 26.5)

This cyst develops from the remnants of the reduced enamel epithelium after the tooth has formed.

• Age: Usually adolescents or young adults, 20–40-year-olds, occasionally the elderly.

• Frequency: About 20% of all cysts.

• Site: Associated with the crown of an unerupted and displaced tooth, typically teeth where eruption is impeded, e.g.  and

and  .

.

• Size: Very variable, cyst suspected if follicular space exceeds 3 mm but may grow to several centimetres in diameter and extend up into the ramus.

• Shape: —Round or oval, typically enveloping the crown symmetrically

Note: The term eruption cyst is used to describe a dentigerous cyst when it is in the soft tissues overlying the unerupted tooth.

Odontogenic keratocyst (keratocystic odontogenic tumour) (Fig. 26.6)

• Age: Very variable, peak incidence between second and third decades.

• Site: —Posterior body/angle of the mandible extending into the ramus

• Size: Variable, but often large in the mandible.

• Shape: —Oval, extending along the body of the mandible with little mediolateral expansion

• Outline: — Smooth and scalloped

• Radiodensity: Uniformly radiolucent.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – minimal displacement, rarely resorbed

Non-odontogenic cysts

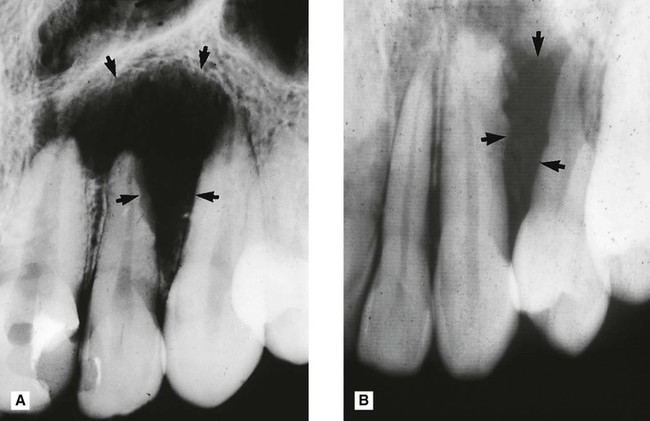

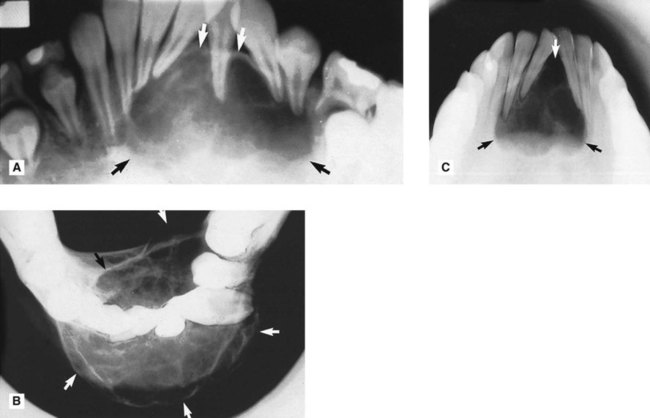

Nasopalatine duct/incisive canal cyst (Fig. 26.7)

This cyst develops from epithelial remnants of the nasopalatine duct or incisive canal.

• Age: Variable, but most frequently detected in middle age (40–60-year-olds).

• Frequency: Most common of all non-odontogenic cysts, affecting about 1% of total population.

• Site: Midline, anterior maxilla just posterior to the upper central incisors.

• Size: Variable, but usually from 6 mm to several centimetres in diameter.

• Shape: —Round or oval (superimposition of the nasal septum or anterior nasal spine may cause the cyst to appear heart-shaped or resemble an inverted tear drop)

• Radiodensity: Uniformly radiolucent but radiopaque shadows sometimes superimposed.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – distal displacement, rarely resorbed

Note: Differentiation is sometimes required between a nasopalatine duct cyst and a large normal nasopalatine foramen. Several features need to be considered including:

• Size – if over 6 mm, a cyst is more likely

• Shape – foramina are usually oval or irregular

• Outline – foramina are usually well defined laterally but not all the way round

• Relative radiodensity – a cyst tends to be more radiolucent having resorbed bone.

Bone cysts or pseudocysts

Simple (solitary) bone cyst (Fig. 26.8)

• Age: Children or young adults, peak incidence in second decade.

• Site: Mandible, particularly anteriorly and in the premolar/molar region.

• Size: Variable, up to several centimetres in diameter.

• Outline: — Smooth and undulating

• Radiodensity: Uniformly radiolucent.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – minimal or no displacement, very rarely resorbed

Typical radiographic features of tumours and tumour-like lesions

Odontogenic tumours

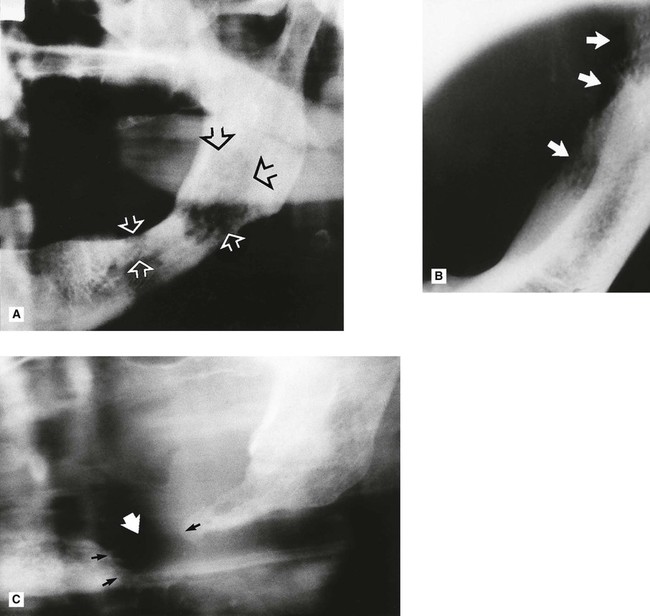

Ameloblastoma (Fig. 26.9)

Solid/multicystic ameloblastoma

• Age: Adults 30–60 years old.

• Frequency: Rare, but still the most common odontogenic tumour.

• Site: —80% posterior body/angle/ramus of mandible

• Size: Very variable depending on the age of the lesion, may become very large if neglected and cause gross facial asymmetry.

• Shape: —Multilocular, distinct septa dividing the lesion into compartments with large, apparently discrete areas centrally and with smaller areas on the periphery

— Occasionally unilocular in early stages

— Rarely honeycomb or soap-bubble appearance or multicystic.

• Outline: — Smooth and scalloped

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent with internal radiopaque septa.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth displaced, loosened, often resorbed

Other epithelial odontogenic tumours

• Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour (CEOT) or Pindborg tumour

• Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour (AOT)

• Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour (calcifying odontogenic cyst).

However, as the name of a couple of them suggests, these lesions often develop internal calcifications and more typically present as lesions of variable radiopacity. They are therefore described in detail with appropriate examples in Chapter 27. A brief summary of each is outlined below.

Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour (CEOT), Pindborg tumour

This rare odontogenic tumour usually presents in the premolar/molar region of the mandible in 20–60-year-old adults. They can be either unilocular or multilocular, but tend to remain relatively small although they can cause expansion of surrounding cortical bone. They are often associated with an unerupted tooth particularly  . The outline of the lesion tends to be of variable definition and cortication but is frequently scalloped. They are often radiolucent in their early stages; then numerous scattered radiopacities usually become evident within the lesion, often most prominent around the crown of any associated unerupted tooth. This appearance is sometimes described as driven snow. Adjacent teeth can be either displaced and/or resorbed (see Fig. 27.8).

. The outline of the lesion tends to be of variable definition and cortication but is frequently scalloped. They are often radiolucent in their early stages; then numerous scattered radiopacities usually become evident within the lesion, often most prominent around the crown of any associated unerupted tooth. This appearance is sometimes described as driven snow. Adjacent teeth can be either displaced and/or resorbed (see Fig. 27.8).

Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma

These rare, unilocular or multilocular odontogenic tumours closely resemble ameloblastic fibromas (see Fig. 26.10), and also affect children. However, they are often associated with an unerupted tooth and usually contain enamel or dentine, either as multiple small opacities or as a solid mass (see Fig. 27.9).

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour (AOT)

Another rare odontogenic tumour, but unusually the most frequent site affected, is the anterior maxilla in the incisor/canine region. Young adults are usually affected. The lesion tends to be unilocular, round or oval, and often surrounds an entire unerupted tooth. When radiolucent in their early stages, they can closely resemble a dentigerous cyst. However, as the lesion matures, small opacities (snowflakes) within the central radiolucency may be seen peripherally. Adjacent teeth are often displaced as the lesion expands but are rarely resorbed (see Fig. 27.10).

Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour (calcifying odontogenic cyst or Gorlin’s cyst)

The new name of this lesion reflects its classification by the WHO as an odontogenic tumour. It presents typically anteriorly in either the mandible or the maxilla as a unilocular, well-defined, well-corticated radiolucency resembling any other odontogenic cyst. It can affect any age group having been reported in patients from 5 to 92 years old. One-third of cases are associated with an unerupted tooth or odontome. As the lesion matures, a variable amount of calcified material, of tooth-like density, becomes evident scattered throughout the radiolucency. The opacities can range from small flecks to large masses. Adjacent teeth are usually displaced and/or resorbed (see Fig. 27.11).

Odontogenic fibroma (Fig. 26.11)

• Epithelium-poor originating from the dental follicle

• Epithelium-rich originating from the periodontal ligament.

Typically lesions present as cyst-like well defined, unilocular radiolucencies with dense corticated margin. Rarely calcified material may develop internally and adjacent teeth may be displaced.

Odontogenic myxoma (Fig. 26.12)

• Age: Young adults – most diagnosed in the 2nd–4th decades.

• Frequency: Rare, but the third most common odontogenic tumour.

• Site: Posterior mandible or posterior maxilla.

• Size: Variable, but may become very large if untreated.

• Shape: —Multilocular (honeycomb or soap-bubble)

• Outline: — Smooth and often scalloped

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent with fine internal radiopaque septa or trabeculae often arranged at right angles to one another, producing an appearance sometimes described as resembling the strings of a tennis racket or the letters X and Y.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth displaced and loosened, occasionally resorbed

Radiolucent non-odontogenic tumours

Intrinsic primary benign bone tumours

Central haemangioma (Fig. 26.13)

• Most commonly a multilocular, expanding lesion which may be associated with displacement and resorption of associated teeth. The size and number of locules can vary considerably, and, if numerous, can present with a honeycomb appearance.

• A moderately well-defined zone of radiolucency within which the trabecular spaces are enlarged and the trabeculae themselves are coarse and thick and are said to be arranged like a hub or the spokes of a wheel.

• Rarely, a relatively well-defined, round, cyst-like radiolucency – not distinctive in any way.

• Large lesions may cause cortical expansion, occasionally producing the sunray or sunburst appearance.

Intrinsic primary malignant bone tumours

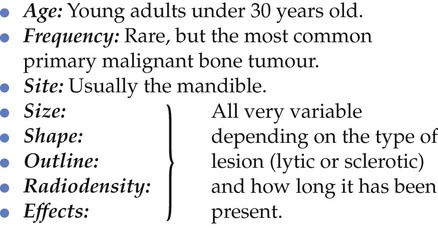

Osteosarcoma (Fig. 26.14)

• Osteolytic – no neoplastic bone formation.

• Osteogenic/osteosclerotic – neoplastic osteoid and bone formed.

• Mixed lytic and sclerotic – patches of neoplastic bone formed.

Later features:

– Unilocular, ragged area of radiolucency

– Poorly defined, moth-eaten outline

– So-called spiking resorption and/or loosening of associated teeth

• Osteogenic and mixed lesions:

– Poorly defined radiolucent area

– Variable internal radiopacity with obliteration of the normal trabecular pattern

– Perforation and expansion of the cortical margins by stretching the periosteum, producing the classic, but rare sun ray or sunburst appearance (see Ch. 27)

Extrinsic primary malignant tumours involving bone

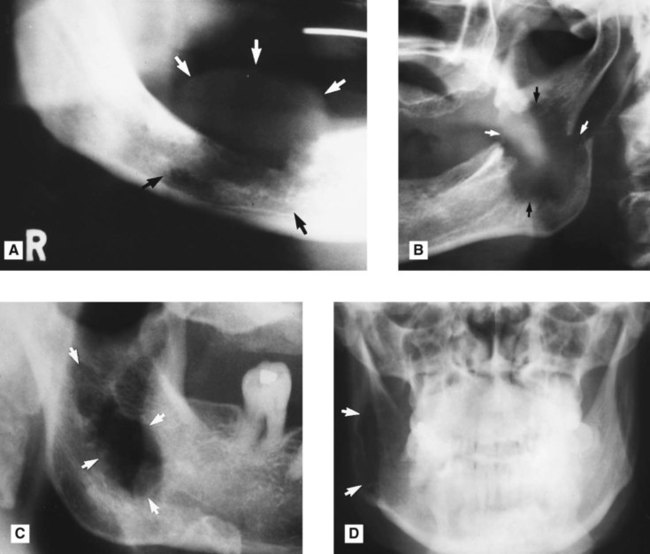

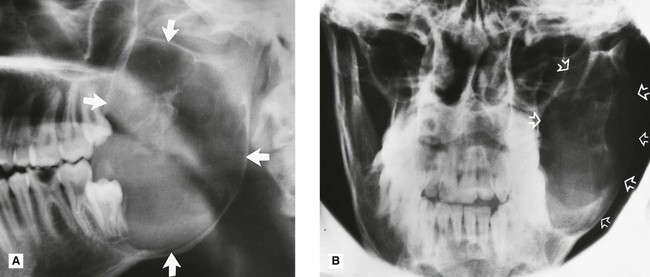

Squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 26.15)

• Age: Adults over 50 years old.

• Frequency: Rare, but the most common oral malignant tumour.

• Site: Mandible, or maxilla if originating in the antrum.

• Shape: Irregular area of bone destruction often initially saucer-shaped.

• Outline: — Irregular and moth-eaten

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent, radiodensity dependent on degree of destruction.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth may be displaced, loosened and/or resorbed or left floating in space

Secondary (metastatic) bone tumours (Fig. 26.16)

Carcinomas from the bronchus, breast, prostate, kidney and thyroid sometimes metastasize to the jaws and produce the typical destructive radiolucency of a malignant lesion (see Ch. 21).

• Age: Adults over 40 years old.

• Frequency: Rare, but the second most common malignant tumours of the jaws.

• Site: Usually centrally in the mandible, molar and premolar regions, occasionally at the apex of a tooth.

• Size: Variable, dependent on the length of time the lesion has been present.

• Shape: Irregular area or areas of bone destruction.

• Outline: — Irregular and moth-eaten

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent, but some carcinomas from the prostate and breast may be osteogenic and show areas of bone production/sclerosis.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth may be displaced, loosened and/or resorbed

Note: The radiographic appearance, while strongly indicating a destructive malignant lesion, does not enable the distinction between a primary or secondary tumour to be made.

Lymphoreticular tumours of bone (Fig. 26.17)

Others

• Large cell (anaplastic) lymphoma – adults under 40 years

These lymphoreticular tumours are rare and apart from the age group predilection (shown above), they present in a similar, relatively non-specific manner. Radiographically they usually present as expansile, destructive, poorly defined, radiolucent areas – suggestive of malignant disease.

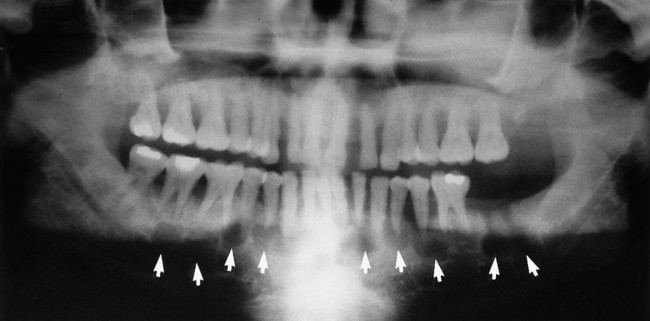

Langerhans cell disease (histiocytosis X)

• Solitary eosinophilic granuloma – localized to the skeleton, affecting adolescents and young adults (see Fig. 26.18)

• Multifocal eosinophilic granuloma (Hand–Schüller–Christian disease) – chronic and wide-spread, begins in childhood but may not be fully developed until early adulthood, 20–30 years

• Letterer–Siwe disease – acute or subacute and widespread, affecting children under three years old.

Radiographically, the bone lesions (in whatever parts of the skeleton are affected) are similar in all three diseases.

• Site: Multiple lesions (in multifocal eosinophilic granuloma and Letterer–Siwe disease only) throughout the skeleton, occasionally solitary lesion, affecting:

• Size: Small, 1–2 cm in diameter.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – not resorbed, but the periodontal bone support is sometimes destroyed so that they appear to be floating or standing in space

Note: Appearance not suggestive of malignant disease.

Typical radiographic features of bone-related lesions

Giant cell lesions

Central giant cell lesion (granuloma) (Fig. 26.19)

• Age: All ages can be affected but usually young adolescents and adults under 30 years old. One-third of cases reported in patients under 20.

• Site: Mandible – all parts particularly premolar/molar region and anteriorly often crossing the midline.

• Shape: Multilocular, may be unilocular in early stages.

• Outline: — Smooth and scalloped

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent, larger lesions have thin internal septa or trabeculae producing the multilocular, or sometimes honeycomb appearance.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth often displaced, sometimes resorbed

Based on their clinical and radiological effects on adjacent structures, central giant cell lesions are sometimes subdivided into two categories:

• Non-aggressive, which exhibit slow-growing, benign behaviour

• Aggressive, which show the typical features of rapidly growing, destructive lesions.

Brown tumours in hyperparathyroidism

The general radiological features of hyperparathyroidism are discussed in detail in Chapter 31. A few patients with this disease, in addition to the generalized decrease in bone density, also develop circumscribed, cyst-like radiolucencies. Histologically and radiologically these individual lesions (so-called brown tumours) are indistinguishable from central giant cell lesions (see earlier).

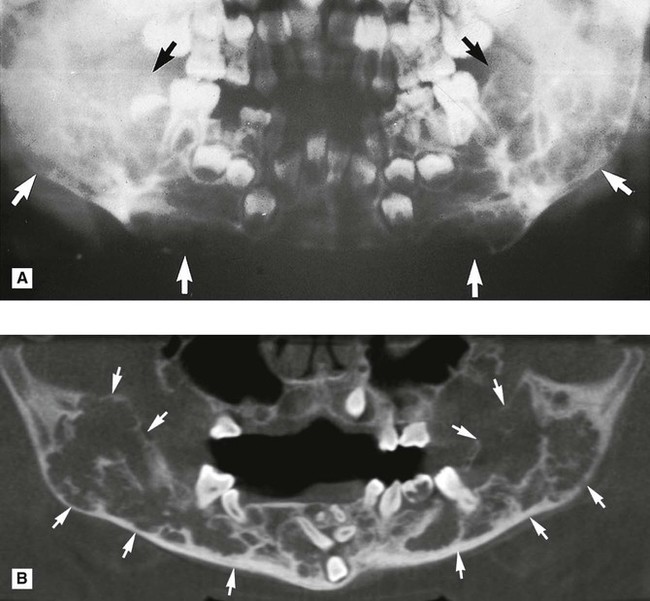

Cherubism (Fig. 26.20)

• Age: Children, 2–6 years old.

• Site: — Angle/posterior mandible – bilateral

• Size: Variable, up to several centimetres in diameter, and may fill the whole jaw.

• Radiodensity: Radiolucent with internal radiopaque septa producing a multilocular appearance.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – gross displacement of deciduous and permanent teeth, occasionally resorbed, deciduous teeth sometimes exfoliated early

Aneurysmal bone cyst (Fig. 26.21)

Bone-related lesions – osseous dysplasias

The 2005 WHO Classification, shown in Table 26.1, now categorizes fibro-cemento-osseous lesions as osseous dysplasias and includes four conditions:

They are all skeletal disorders in which bone is replaced by fibrous tissue which in turn is replaced by bone or mineralized tissue to a varying degree as the lesions age. Thus, in their early stages all the osseous dysplasias can present as cyst-like radiolucencies, although they are only sometimes seen clinically at this stage. It is more common to see them in their later stages when they present as mixed radiolucent/radiopaque lesions with varying degrees of opacity. Two radiolucent examples are shown here (Figs 26.22 and 26.23). The more radiopaque lesions are discussed and illustrated in Chapter 27.

Periapical osseous dysplasia (Fig. 26.22)

• Age: Middle-aged adults (typically black women).

• Site: Apices of vital lower incisor teeth.

• Size: Small, usually only up to 5–6 mm in diameter.

• Outline: — Variable but usually poorly defined

• Radiodensity: — Early stage – radiolucent

— Intermediate stage – radiolucent with patchy opacity within the radiolucency

— Late stage – densely radiopaque but surrounded by a thin radiolucent line.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – not displaced, not resorbed, typically vital, with intact periodontal ligament space, but lamina dura may be discontinuous

Florid osseous dysplasia (Fig. 26.23)

• Age: Middle-aged adults (typically black women).

• Site: Widespread, often in all four quadrants (dentulous and edentulous) but associated with the apices of the teeth if present.

• Size: Variable, but individual lesions up to 2 cm in diameter.

• Outline: — Smooth but lobular

• Radiodensity: —Early stage – multiple radiolucencies

— Intermediate stage – multiple radiolucencies with gradually increasing patchy internal opacities

— Late stage – multiple irregular dense radiopacities with individual lesions, sometimes surrounded by a thin radiolucent line.

• Effects: —Adjacent teeth – not displaced, not resorbed, typically vital

Other bone-related lesions

The other bone-related lesions that could present as a radiolucency include:

• Fibrous dysplasia (see Chapters 27 and 28 as more commonly mixed radiodensity)

• Ossifying fibroma (see Chapter 27 as more commonly mixed radiodensity)

Footnote

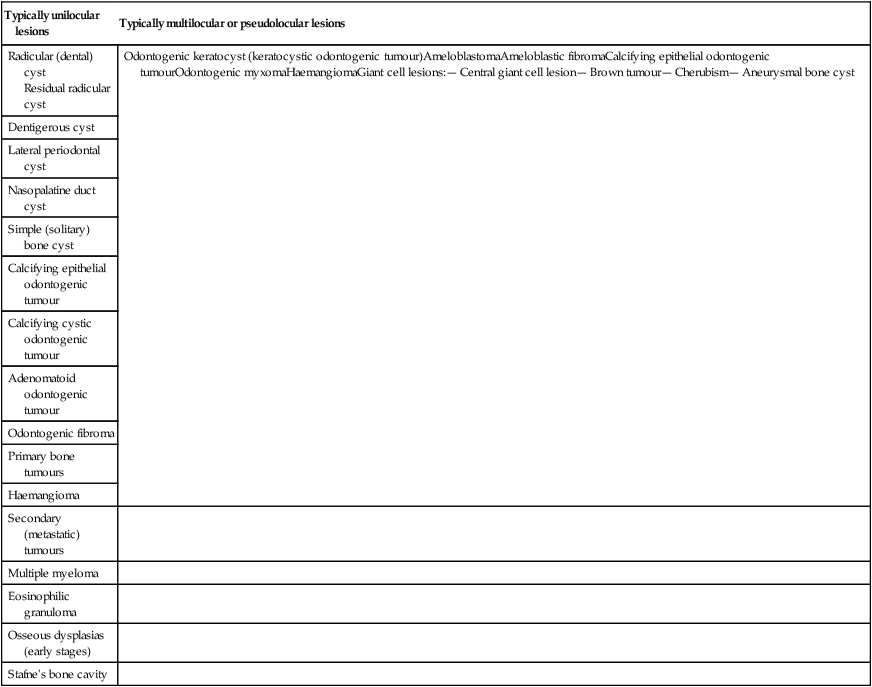

For revision purposes, Table 26.2 summarizes those lesions that present typically as unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies.

Table 26.2

Summary of the main unilocular and multilocular radiolucent lesions

| Typically unilocular lesions | Typically multilocular or pseudolocular lesions |

| Radicular (dental) cyst Residual radicular cyst |

Odontogenic keratocyst (keratocystic odontogenic tumour)AmeloblastomaAmeloblastic fibromaCalcifying epithelial odontogenic tumourOdontogenic myxomaHaemangiomaGiant cell lesions:— Central giant cell lesion— Brown tumour— Cherubism— Aneurysmal bone cyst |

| Dentigerous cyst | |

| Lateral periodontal cyst | |

| Nasopalatine duct cyst | |

| Simple (solitary) bone cyst | |

| Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour | |

| Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour | |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour | |

| Odontogenic fibroma | |

| Primary bone tumours | |

| Haemangioma | |

| Secondary (metastatic) tumours | |

| Multiple myeloma | |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | |

| Osseous dysplasias (early stages) | |

| Stafne’s bone cavity |

To access the self assessment questions for this chapter please go to www.whaitesessentialsdentalradiography.com

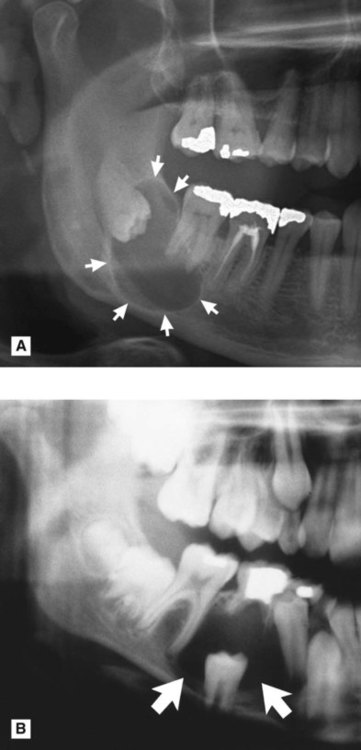

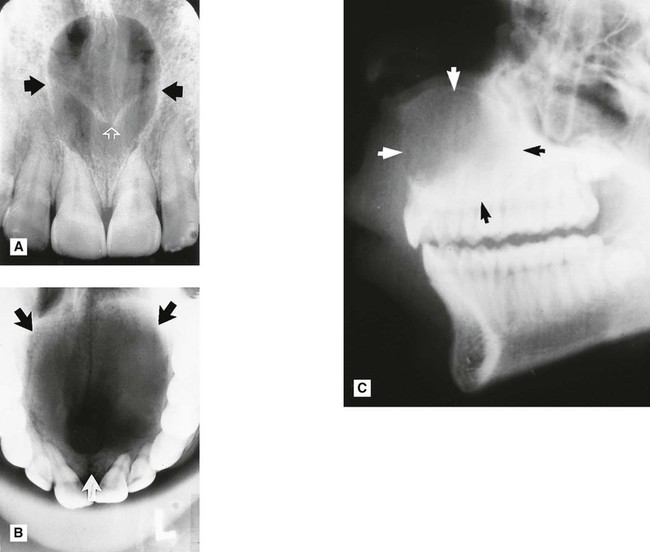

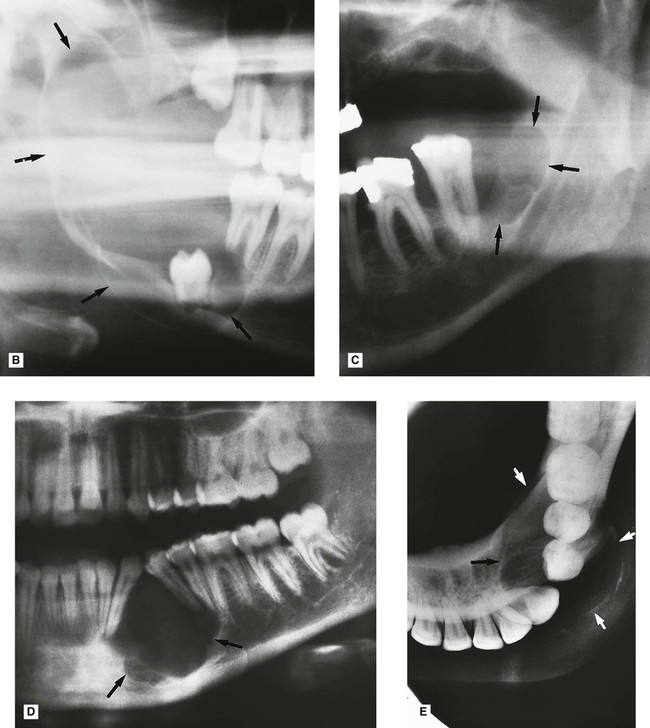

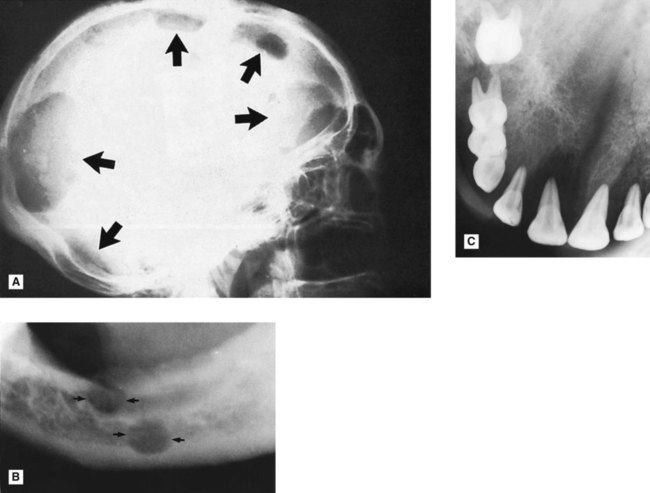

. B Upper standard occlusal showing a large radicular cyst associated with the root-filled

. B Upper standard occlusal showing a large radicular cyst associated with the root-filled  . C Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a typical unilocular radicular cyst associated with the non-vital

. C Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a typical unilocular radicular cyst associated with the non-vital  .

.

and

and  . Although the adjacent premolar was restored, it was vital and symptom free.

. Although the adjacent premolar was restored, it was vital and symptom free. />

/>

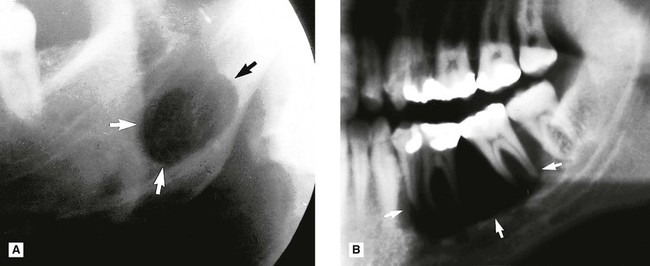

. B Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a unilocular central dentigerous cyst (arrowed) associated with the unerupted and inferiorly displaced

. B Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a unilocular central dentigerous cyst (arrowed) associated with the unerupted and inferiorly displaced  . C Right side of a lower 90° occlusal of the same patient showing the typical buccal expansion (arrowed).

. C Right side of a lower 90° occlusal of the same patient showing the typical buccal expansion (arrowed). />

/> />

/>

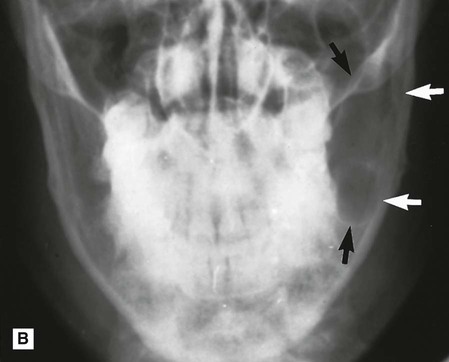

. B PA jaws of the same patient showing that it has caused minimal mediolateral expansion (arrowed). C Left side of a panoramic radiograph showing a very large multilocular odontogenic keratocyst (arrowed) occupying almost all the left side of the mandible.

. B PA jaws of the same patient showing that it has caused minimal mediolateral expansion (arrowed). C Left side of a panoramic radiograph showing a very large multilocular odontogenic keratocyst (arrowed) occupying almost all the left side of the mandible. by enfolding so resembling a dentigerous cyst.

by enfolding so resembling a dentigerous cyst.

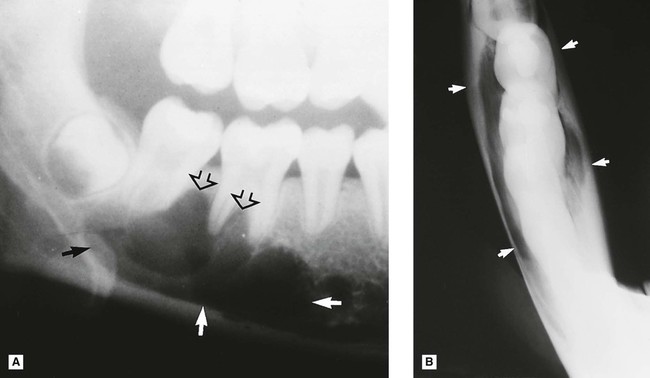

. C Left side of a panoramic radiograph showing bilocular ameloblastoma (arrowed) distal to the molar. D Part of a panoramic radiograph showing an ameloblastoma in a more unusual anterior position causing displacement of the adjacent teeth. E Lower occlusal of the same patient showing the buccolingual extent of the lesion (arrowed).

. C Left side of a panoramic radiograph showing bilocular ameloblastoma (arrowed) distal to the molar. D Part of a panoramic radiograph showing an ameloblastoma in a more unusual anterior position causing displacement of the adjacent teeth. E Lower occlusal of the same patient showing the buccolingual extent of the lesion (arrowed).

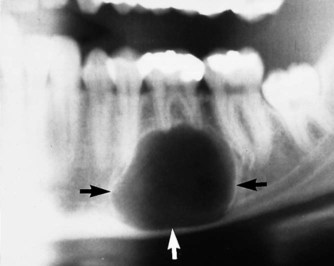

which was clinically vital. Histopathology confirmed an odontogenic fibroma.

which was clinically vital. Histopathology confirmed an odontogenic fibroma.

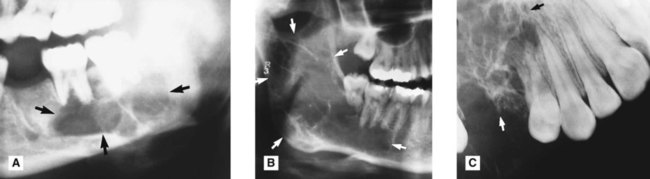

showing a poorly defined ragged area of radiolucency (arrowed) with resorption of the lateral aspect of

showing a poorly defined ragged area of radiolucency (arrowed) with resorption of the lateral aspect of  root. Biopsy revealed an osteolytic osteosarcoma. B Periapical showing a similar smaller poorly defined area of bone destruction between

root. Biopsy revealed an osteolytic osteosarcoma. B Periapical showing a similar smaller poorly defined area of bone destruction between  (arrowed) which was again shown to be an osteosarcoma.

(arrowed) which was again shown to be an osteosarcoma.

to appear to be floating in space.

to appear to be floating in space.

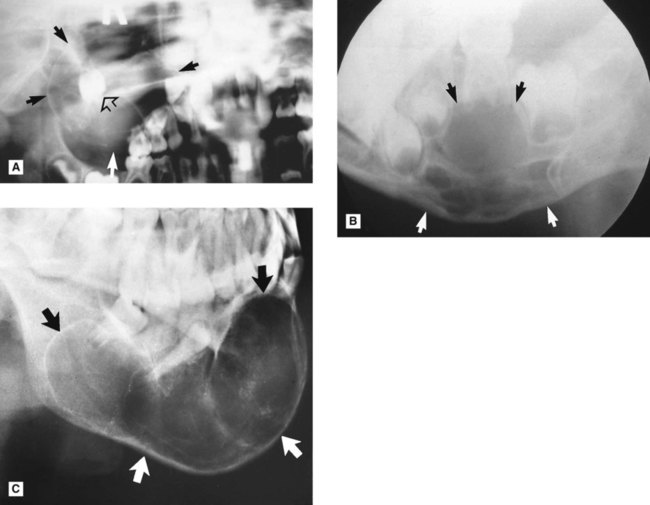

. B PA jaws of the same patient showing ballooning expansion (arrowed).

. B PA jaws of the same patient showing ballooning expansion (arrowed).

show evidence of internal calcification (open arrows).

show evidence of internal calcification (open arrows).