CHAPTER 21 Diencephalon

The diencephalon is part of the prosencephalon (forebrain), which develops from the foremost primary cerebral vesicle and differentiates into a caudal diencephalon and rostral telencephalon. The cerebral hemispheres develop from the sides of the telencephalon, each containing a lateral ventricle. The sites of evagination become the interventricular foramina, through which the two lateral ventricles and midline third ventricle communicate. The diencephalon corresponds largely to the structures that develop lateral to the third ventricle. The lateral walls of the diencephalon form the epithalamus most superiorly, the thalamus centrally and the subthalamus and hypothalamus most inferiorly.

THALAMUS

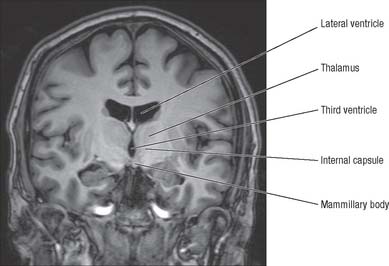

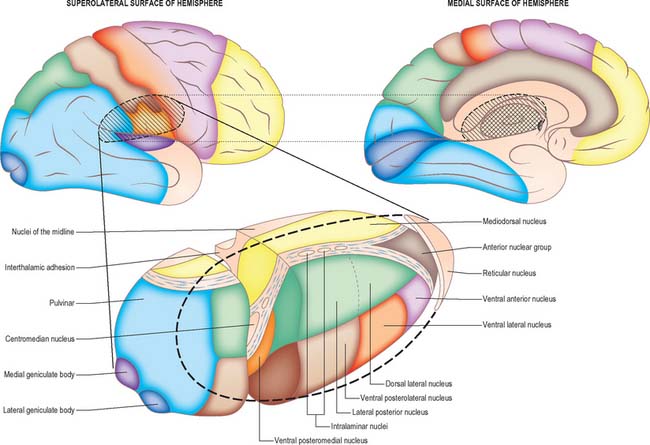

The thalamus is an ovoid nuclear mass, about 4 cm long, which borders the dorsal part of the third ventricle (Figs 21.1, 21.2). The narrow anterior pole lies close to the midline, and forms the posterior boundary of the interventricular foramen. Posteriorly, an expansion, the pulvinar, extends beyond the third ventricle to overhang the superior colliculus (see Fig. 19.3). The brachium of the superior colliculus (superior quadrigeminal brachium) separates the pulvinar above from the medial geniculate body below. A small oval elevation, the lateral geniculate body, lies lateral to the medial geniculate.

The superior (dorsal) surface of the thalamus (see Fig. 19.3) is covered by a thin layer of white matter, the stratum zonale. It extends laterally from the line of reflection of the ependyma (taenia thalami), and forms the roof of the third ventricle. This curved surface is separated from the overlying body of the fornix by the choroid fissure with the tela choroidea within it. More laterally, it forms part of the floor of the lateral ventricle. The lateral border of the superior surface of the thalamus is marked by the stria terminalis and overlying thalamostriate vein, which separate the thalamus from the body of the caudate nucleus. Laterally, a slender sheet of white matter, the external medullary lamina, separates the main body of the thalamus from the reticular nucleus. Lateral to this, the thick posterior limb of the internal capsule lies between the thalamus and the lentiform complex.

The medial surface of the thalamus is the superior (dorsal) part of the lateral wall of the third ventricle. It is usually connected to the contralateral thalamus by an interthalamic adhesion behind the interventricular foramina (see Fig. 16.7). The boundary with the hypothalamus is marked by an indistinct hypothalamic sulcus, which curves from the upper end of the cerebral aqueduct to the interventricular foramen. The thalamus is continuous with the midbrain tegmentum, the subthalamus and the hypothalamus.

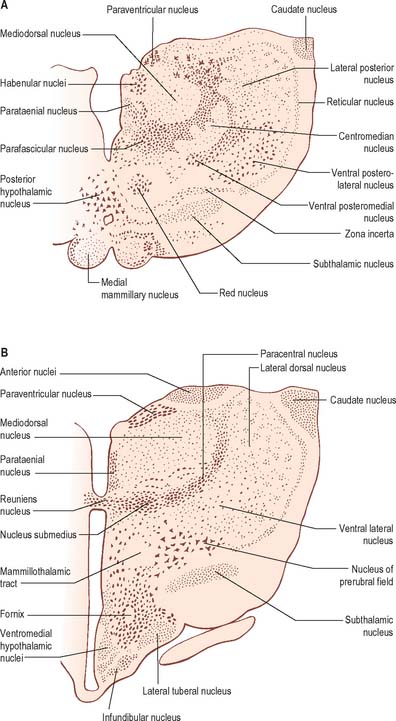

Internally, the greater part of the thalamus is divided into anterior, medial and lateral nuclear groups by a vertical Y-shaped sheet of white matter, the internal medullary lamina (Figs 21.3, 21.4). In addition, intralaminar nuclei lie embedded within the internal medullary lamina and midline nuclei abut the lateral walls of the third ventricle. The reticular nucleus forms a shell-like lateral covering to the main nuclear mass, separated from it by an external medullary lamina of nerve fibres.

In general, thalamic nuclei both project to and receive fibres from the cerebral cortex (Fig. 21.4). The whole cerebral cortex, including neocortex, paleocortex of the piriform lobe and archicortex of the hippocampal formation, is reciprocally connected with the thalamus. The thalamus is the major route by which subcortical neuronal activity influences the cerebral cortex, and the greatest input to most thalamic nuclei comes from the cerebral cortex.

ANTERIOR THALAMIC NUCLEI

The anterior group of nuclei are enclosed between the arms of the Y-shaped internal medullary lamina, and underlie the anterior thalamic tubercle (see Figs 19.3, 21.4). Three subdivisions are recognized: the largest is the anteroventral nucleus, the others being the anteromedial and anterodorsal nuclei.

MEDIAL THALAMIC NUCLEI

The mediodorsal nucleus appears to be involved in a wide variety of higher functions. Damage may lead to a decrease in anxiety, tension, aggression or obsessive thinking. There may also be transient amnesia, with confusion developing particularly over the passage of time. Much of the neuropsychology of medial nuclear damage reflects defects in functions similar to those performed by the prefrontal cortex, with which it is closely linked. The effects of ablation of the mediodorsal nuclei parallel, in part, the results of prefrontal lobotomy.

LATERAL THALAMIC NUCLEI

Ventral lateral nucleus

Approximately 70% of VL neurones are large relay neurones, and the other 30% are local circuit interneurones. Responses can be recorded in VL thalamus during both passive and active movement of the contralateral body. The topography of its connections, and recordings made within the nucleus, suggest that VLc contains a body representation comparable to that in the ventral posterior nucleus. In patients with tremor, clusters of VL neurones fire in bursts that are synchronous with peripheral tremor: these cells have been designated as ‘tremor cells’. Stereotaxic surgery of the ventral lateral nucleus is sometimes used in the treatment of essential tremor. In the past, thalamotomy was used extensively for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. The internal segment of the globus pallidus and the subthalamic nucleus are now the preferred neurosurgical targets for Parkinson’s disease (see Ch. 22).

Medial geniculate nucleus

The medial geniculate nucleus, which is a part of the auditory pathway (see Ch. 37), is located within the medial geniculate body, a rounded elevation situated posteriorly on the ventrolateral surface of the thalamus, and separated from the pulvinar by the superior quadrigeminal brachium. It receives fibres travelling in the inferior quadrigeminal brachium. Three major subnuclei, medial, ventral and dorsal, are recognized within it. The inferior brachium separates the medial (magnocellular) nucleus, which consists of sparse, deeply staining neurones, from the lateral nucleus, which is made up of medium-sized, densely packed and darkly staining cells. The dorsal nucleus overlies the ventral nucleus and expands posteriorly; it is, therefore, sometimes known as the posterior nucleus of the medial geniculate. It contains small- to medium-sized, pale-staining cells, which are less densely packed than those of the lateral nucleus. The ventral nucleus receives fibres from the central nucleus of the ipsilateral inferior colliculus via the inferior quadrigeminal brachium and also from the contralateral inferior colliculus. The nucleus contains a complete tonotopic representation. Low-pitched sounds are represented laterally, and progressively higher-pitched sounds are encountered as the nucleus is traversed from lateral to medial. The dorsal nucleus receives afferents from the pericentral nucleus of the inferior colliculus and from other brain stem nuclei of the auditory pathway. A tonotopic representation has not been described in this subdivision and cells within the dorsal nucleus respond to a broad range of frequencies. The magnocellular medial nucleus receives fibres from the inferior colliculus and from the deep layers of the superior colliculus. Neurones within the magnocellular subdivision may respond to modalities other than sound. However, many cells respond to auditory stimuli, usually to a wider range of frequencies than neurones in the ventral nucleus. Many units show evidence of binaural interaction, with the leading effect arising from stimuli in the contralateral cochlea. The ventral nucleus projects primarily to the primary auditory cortex. The dorsal nucleus projects to auditory areas surrounding the primary auditory cortex. The magnocellular division projects diffusely to auditory areas of the cortex and to adjacent insular and opercular fields.

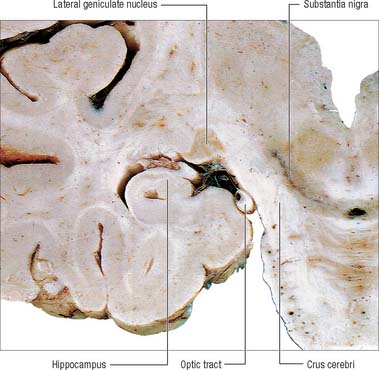

Lateral geniculate nucleus

The lateral geniculate body, which is part of the visual pathway (see Ch. 40), is a small, ovoid, ventral projection from the posterior thalamus (Fig. 21.5). The superior quadrigeminal brachium enters the posteromedial part of the lateral geniculate body dorsally, lying between the medial geniculate body and the pulvinar.

Fig. 21.5 Coronal section through the brain showing the lateral geniculate nucleus.

(Photograph by Kevin Fitzpatrick on behalf of GKT School of Medicine, London.)

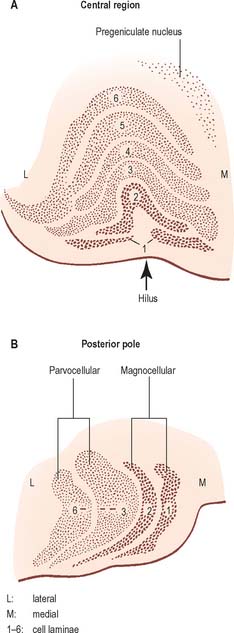

The lateral geniculate nucleus is an inverted, somewhat flattened, U-shaped nucleus and is laminated. Its internal organization is usually described on the basis of six laminae, although seven or eight may be present. The laminae are numbered 1 to 6, from the innermost ventral to the outermost dorsal (Fig. 21.6). Laminae 1 and 2 consist of large cells, the magnocellular layers, whereas layers 4 to 6 have smaller neurones, the parvocellular laminae. The apparent gaps between laminae are called the interlaminar zones. Most ventrally an additional superficial, or S, lamina is recognized.

The lateral geniculate nucleus receives a major afferent input from the retina. The contralateral nasal hemiretina projects to laminae 1, 4 and 6, whereas the ipsilateral temporal hemiretina projects to laminae 2, 3 and 5. The parvocellular laminae receive axons predominantly of X-type retinal ganglion cells, i.e. more slowly conducting cells with sustained responses to visual stimuli. The faster conducting, rapidly adapting Y-type retinal ganglion cells project mainly to the magnocellular laminae 1 and 2, and give off axonal branches to the superior colliculus. A third type of retinal ganglion cell, the W cells, which have large receptive fields and slow responses, project to both the superior colliculus and the lateral geniculate nucleus, where they terminate particularly in the interlaminar zones and in the S lamina.

The lateral geniculate nucleus is organized in a visuotopic manner and it contains a precise map of the contralateral visual field. The vertical meridian is represented posteriorly, the peripheral anteriorly, the upper field laterally, and the lower field medially. Similar precise, point-to-point, representation is also found in the projection of the lateral geniculate nucleus to the visual cortex. Radially arranged inverted pyramids of neurones in all laminae respond to a single, small area of the contralateral visual field and project to a circumscribed area of cortex. The termination of geniculocortical axons in the visual cortex is considered in detail elsewhere (see Ch. 23).

Pulvinar

The pulvinar corresponds to the posterior expansion of the thalamus, which overhangs the superior colliculus (Fig. 21.4). It has three major subdivisions, which are the medial, lateral and inferior pulvinar nuclei. The medial pulvinar nucleus is dorsomedial and consists of compact, evenly spaced, neurones. The inferior pulvinar nucleus lies laterally and inferiorly, and is traversed by bundles of axons in the mediolateral plane, an arrangement which confers a fragmented appearance of horizontal cords or sheets of cells separated by fibre bundles. The inferior pulvinar nucleus lies most inferiorly and laterally and is a more homogeneous collection of cells.

INTRALAMINAR NUCLEI

The term intralaminar nuclei refers to collections of neurones within the internal medullary lamina of the thalamus (Fig. 21.4). Two groups of nuclei are recognized. The anterior (rostral) group is subdivided into central medial, paracentral and central lateral nuclei. The posterior (caudal) intralaminar group consists of the centromedian and parafascicular nuclei. The designations central medial and centromedian are open to confusion; however, they are an accepted part of the terminology of thalamic nuclei in common usage. The centromedian nucleus is much larger, is considerably expanded in man in comparison with other species, and is importantly related to the globus pallidus, deep cerebellar nuclei and motor cortex. Anteriorly, the internal medullary lamina separates the mediodorsal nucleus from the ventral lateral complex. It is occupied by the paracentral nucleus laterally, and the central medial nucleus ventromedially, as the two laminae converge towards the midline. A little more posteriorly, the central lateral nucleus appears dorsally in the lamina as the latter splits to enclose the lateral dorsal nucleus. More posteriorly, at the level of the ventral posterior nucleus, the lamina splits to enclose the ovoid centromedian nucleus. The smaller parafascicular nucleus lies more medially.

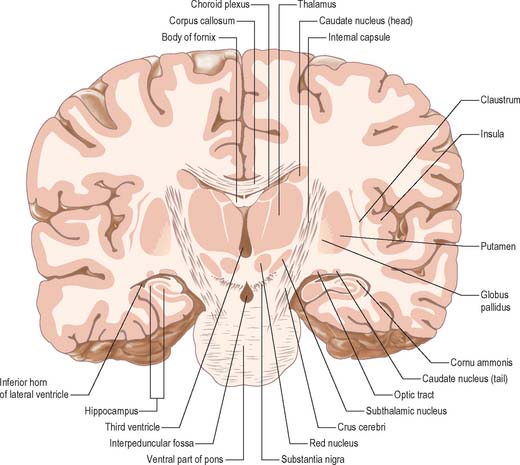

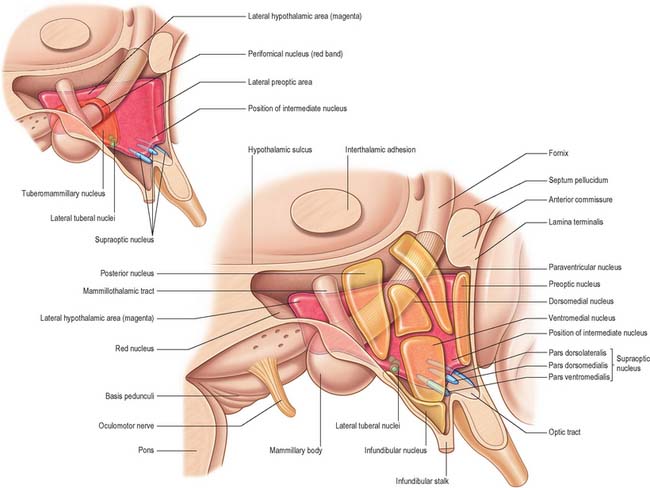

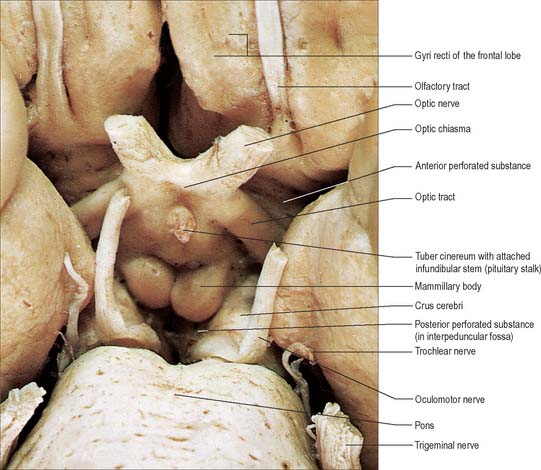

HYPOTHALAMUS

The hypothalamus extends from the lamina terminalis to a vertical plane posterior to the mammillary bodies, and from the hypothalamic sulcus to the base of the brain beneath the third ventricle. It lies beneath the thalamus (Fig. 21.3) and anterior to the tegmental part of the subthalamus and the mesencephalic tegmentum (Figs 21.7, 21.8)). Laterally, it is bordered by the anterior part of the subthalamus, internal capsule and optic tract. Structures in the floor of the third ventricle reach the pial surface in the interpeduncular fossa. From anterior to posterior they are the optic chiasma, the tuber cinereum, tuberal eminences and the infundibular stalk, the mammillary bodies and the posterior perforated substance. The latter lies in the interval between the diverging crura cerebri, and is pierced by small central branches of the posterior cerebral arteries. It contains the small interpeduncular nucleus, which receives terminals of the fasciculus retroflexus of both sides, and has other connections with the mesencephalic reticular formation and mammillary bodies.

Fig. 21.7 The inferior aspect of the hypothalamus and surrounding structures.

(Photograph by Kevin Fitzpatrick on behalf of GKT School of Medicine, London.)

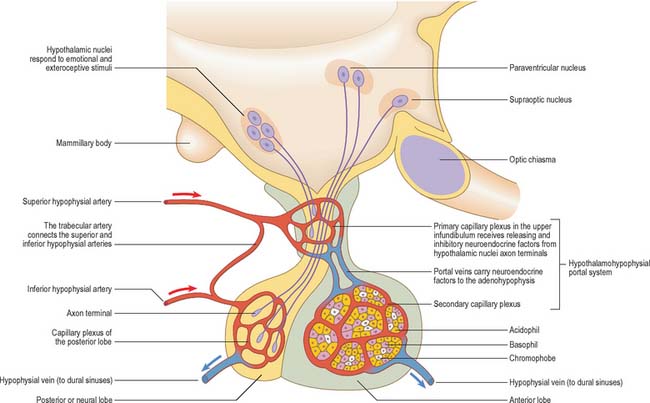

The hypothalamus controls the endocrine system in a variety of ways: through magnocellular neurosecretory projections to the posterior pituitary; through parvocellular neurosecretory projections to the median eminence (these control the endocrine output of the anterior pituitary and thereby the peripheral endocrine organs); and via the autonomic nervous system. The posterior pituitary neurohormones, vasopressin and oxytocin, are primarily involved in the control of osmotic homeostasis and various aspects of reproductive function, respectively. Through its effects on the anterior pituitary, the hypothalamus influences the thyroid gland (thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH), suprarenal cortex (adrenocorticotrophic hormone, ACTH), gonads (luteinizing hormone, LH; follicle stimulating hormone, FSH; prolactin), mammary gland (prolactin), and the processes of growth and metabolic homeostasis (growth hormone, GH).

HYPOTHALAMIC NUCLEI

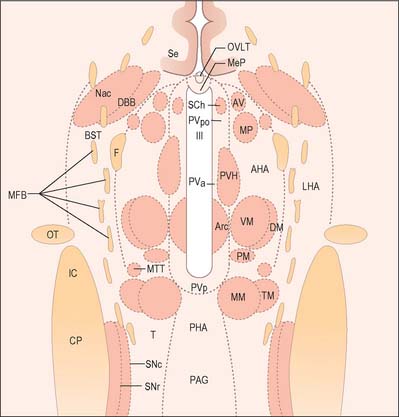

The hypothalamus can be divided anteroposteriorly into chiasmatic (supraoptic), tuberal (infundibulo-tuberal) and posterior (mammillary) regions, and mediolaterally into periventricular, intermediate (medial), and lateral zones. Between the intermediate and lateral zones is a paramedian plane, which contains the prominent myelinated fibres of the column of the fornix, the mammillothalamic tract and the fasciculus retroflexus. For this reason, some authors group the periventricular and intermediate zones as a single medial zone. These divisions are artificial and functional systems cross them. The main nuclear groups and myelinated tracts are illustrated in Figures 21.8 and 21.9.

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

The suprachiasmatic nucleus has two principal subdivisions, ventrolateral and dorsomedial. Retinal fibres terminate in the ventrolateral subdivision, characterized by neurones immunoreactive for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP). This appears to be a general input zone, which also receives afferents from the midbrain raphe and parts of the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. The dorsomedial subdivision has relatively sparse afferent innervation, and characteristically contains parvocellular neurones immunoreactive for arginine vasopressin (AVP). Neurones within the suprachiasmatic nuclei that receive direct retinal input do not respond to pattern, movement or colour. Instead, they operate as luminance detectors, responding to the onset and offset of light, and their firing rates vary in proportion to light intensity, thereby synchronizing to the light–dark cycle.

Neurones producing somatostatin (growth hormone release-inhibiting hormone) are located in the periventricular nucleus. GHRH and somatostatin are secreted in intermittent (3–5 hour) reciprocal pulses, but the origin of the pulses is unclear. A large pulse of GH is secreted at the onset of slow wave sleep. Somatostatin also inhibits release of pituitary thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei

The ventromedial nucleus, lateral hypothalamic area and paraventricular nucleus also influence intermediate metabolism through the autonomic and endocrine systems. These appear to complement the effects on feeding behaviour. Thus, ventromedial stimulation facilitates glucagon release and increases glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis and lipolysis, whereas lateral hypothalamic stimulation causes insulin release and the opposite metabolic effects. Lesions of the ventromedial nucleus also cause increased vagal and decreased sympathetic tone.

CONNECTIONS OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS

Afferent connections

The hypothalamus receives visceral, gustatory and somatic sensory information from the spinal cord and brain stem. It receives largely polysynaptic projections from the nucleus tractus solitarius, probably directly and indirectly via the parabrachial nucleus and medullary noradrenergic cell groups (ventral noradrenergic bundle); collaterals of lemniscal somatic afferents (to the lateral hypothalamus); and projections from the dorsal longitudinal reticular formation. Many enter via the medial forebrain bundle (Fig. 21.9) and periventricular fibre system. Others converge in the midbrain tegmentum, forming the mammillary peduncle to the mammillary body.

The medial forebrain bundle is a loose grouping of fibre pathways that mostly run longitudinally through the lateral hypothalamus (Fig. 21.9). It connects forebrain autonomic and limbic structures with the hypothalamus and brain stem, receiving and giving small fascicles throughout its course. It contains descending hypothalamic afferents from the septal area and orbitofrontal cortex, ascending afferents from the brain stem, and efferents from the hypothalamus.

Efferent connections

The medial mammillary nucleus gives rise to a large ascending fibre bundle, which diverges into the mammillothalamic and mammillotegmental tracts (Fig. 21.9). The mammillothalamic tract ascends through the lateral hypothalamus to reach the anterior thalamic nuclei, whence massive projections radiate to the cingulate gyrus. The mammillotegmental tract curves inferiorly into the midbrain ventral to the medial longitudinal fasciculus, and is distributed to tegmental reticular nuclei.

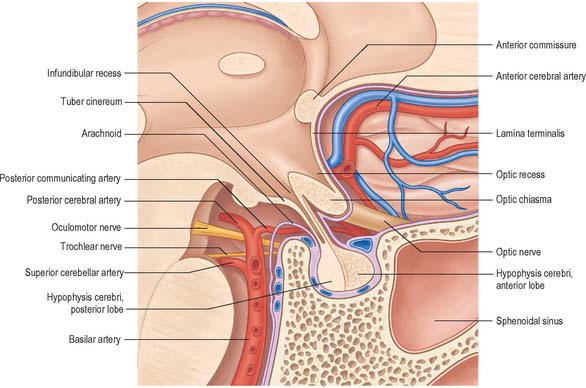

PITUITARY GLAND

The pituitary gland, or hypophysis cerebri (Fig. 21.10; see Fig. 16.7), is a reddish-grey, ovoid body, about 12 mm in transverse and 8 mm in anteroposterior diameter, and with an average adult weight of 500 mg. It is continuous with the infundibulum, a hollow, conical, inferior process from the tuber cinereum of the hypothalamus. It lies within the pituitary fossa of the sphenoid bone, where it is covered superiorly by a circular diaphragma sellae of dura mater. The latter is pierced centrally by an aperture for the infundibulum, and separates the anterior superior aspect of the pituitary from the optic chiasma. Inferiorly, the pituitary is separated from the floor of the fossa by a venous sinus that communicates with the circular sinus. The meninges blend with the pituitary capsule and are not separate layers.

Neurohypophysis

The neurohormones stored in the main part of the neurohypophysis are vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone; ADH), which controls reabsorption of water by renal tubules (see Ch. 74), and oxytocin, which promotes the contraction of uterine smooth muscle (see Ch. 77) in childbirth and the ejection of milk from the breast during lactation. Storage granules containing active hormone polypeptides bound to a transport glycoprotein, neurophysin, pass down axons from their site of synthesis in the neuronal somata (Fig. 21.11).

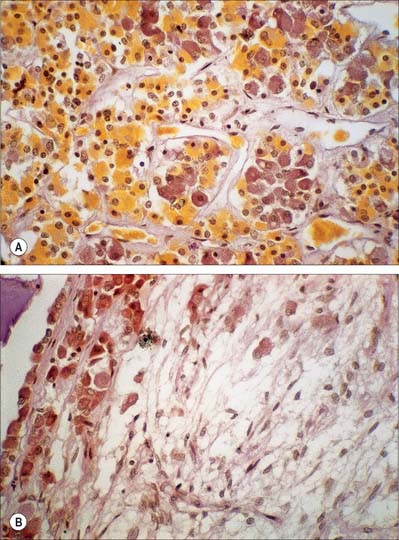

The thin, non-myelinated axons of the neurohypophysis are ensheathed by typical astrocytes in the infundibulum (Fig. 21.12). Near the posterior lobe, astrocytes are replaced by pituicytes, which constitute most of the non-excitable tissue in the neurohypophysis. Pituicytes are dendritic neuroglial cells of variable appearance, often with long processes running parallel to adjacent axons. Typically, their cytoplasmic processes end on the walls of capillaries and sinusoids between nerve terminals. Axons also end in perivascular spaces; they lie close to the walls of sinusoids, but remain separated from them by two basal laminae, one around the nerve endings and the other underlying the fenestrated endothelial cells. The spaces between the basal laminae are occupied by fine collagen fibrils.

Adenohypophysis

The adenohypophysis is highly vascular. It consists of epithelial cells of varying size and shape arranged in cords or irregular follicles, between which lie thin-walled vascular sinusoids supported by a delicate reticular connective tissue (Figs 21.11, 21.12). Most of the hormones synthesized by the adenohypophysis are trophic. They include the peptides growth hormone (GH), involved in the control of body growth, and prolactin (PRL), which stimulates both growth of breast tissue and milk secretion. Glycoprotein trophic hormones are the large pro-opiomelanocortin precursor of adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH), which controls the secretion of certain suprarenal cortical hormones; thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which stimulates growth and secretion of oestrogens in ovarian follicles and spermatogenesis (acting on testicular Sertoli cells); and luteinizing hormone (LH), which induces progesterone secretion by the corpus luteum and testosterone synthesis by Leydig cells in the testis. Pro-opiomelanocortin is cleaved into a number of different molecules including ACTH. β-Lipotropin is released from the pituitary, but its lipolytic function in humans is uncertain. β-Endorphin is another cleavage product released from the pituitary.

A small collection of adenohypophysial tissue lies in the mucoperiosteum of the human nasopharyngeal roof. By 28 weeks in utero it is well vascularized and capable of secretion, receiving blood from the systemic vessels of the nasopharyngeal roof. At this stage it is covered posteriorly by fibrous tissue. This is replaced in the second half of fetal life by venous sinuses, and a trans-sphenoidal portal venous system develops, bringing the nasopharyngeal tissue under the same hypothalamic control as the cranial adenohypophysial tissue. The peripheral vascularity of the pharyngeal hypophysis persists until about the fifth year. The organ is then reinvested by fibrous tissue and presumed to be again controlled by factors present in systemic blood. Though it does not change in size after birth in males, in females it becomes smaller, returning to natal volume during the fifth decade, when once again it may be controlled via a trans-sphenoidal extension of the hypothalamohypophysial portal venous system. The human pharyngeal hypophysis may be a reserve of potential adenohypophysial tissue, which may be stimulated, particularly in females, to synthesize and secrete adenohypophysial hormones in middle age, when intracranial adenohypophysial tissue is beginning to fail.

SUBTHALAMUS

The subthalamus is a complex region of nuclear groups and fibre tracts (Fig. 22.13). The main nuclear groups are the subthalamic nucleus, the reticular nucleus, the zona incerta, the fields of Forel and the pregeniculate nucleus. The rostral poles of the red nucleus and substantia nigra also extend into this area.

SUBTHALAMIC NUCLEUS

The subthalamic nucleus is structurally and functionally related to the basal ganglia and is therefore considered with them in Chapter 22.

EPITHALAMUS

HABENULAR NUCLEI AND STRIA MEDULLARIS

The medial habenular nucleus sends efferent fibres to the interpeduncular nucleus of the midbrain. The lateral habenular nucleus sends fibres to the raphe nuclei and the adjacent reticular formation of the midbrain, the pars compacta of the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area, and to the hypothalamus and basal forebrain.

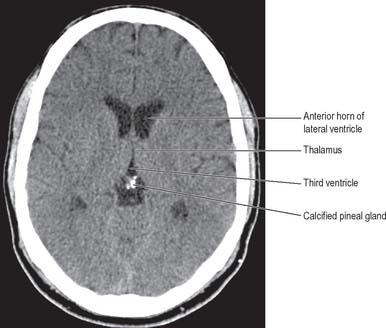

PINEAL GLAND

The pineal gland or epiphysis cerebri (see Figs 16.7, 19.3) is a small, reddish-grey organ, occupying a depression between the superior colliculi. It is inferior to the splenium of the corpus callosum, from which it is separated by the tela choroidea of the third ventricle and the contained cerebral veins. It is enveloped by the lower layer of the tela, which is reflected from the gland to the tectum. The pineal is about 8 mm long. Its base, directed anteriorly, is attached by a peduncle, which divides into inferior and superior laminae, separated by the pineal recess of the third ventricle, and containing the posterior and habenular commissures respectively. Aberrant commissural fibres may invade the gland but do not terminate near parenchymal cells.

From the second decade, calcareous deposits accumulate in pineal extracellular matrix, where they are deposited concentrically as corpora arenacea or ‘brain sand’ (Fig. 21.13). Calcification is often detectable in skull radiographs, when it can provide a useful indicator of a space-occupying lesion if the gland is significantly displaced from the midline.

Jones EG. The Thalamus. New York: Plenum Press, 1985;403-411.

Describes the nomenclature and connections of thalamic nuclei..

Macchi G, Jones EG. Toward an agreement on terminology of nuclear and subnuclear divisions of the motor thalamus. J Neurosurg. 1997;86(4):670-685.

Nieuwenhuys R. Chemoarchitecture of the Brain. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1985.

Describes the connections and neurochemistry of the hypothalamus..