111 Diarrhea

Pathophysiology

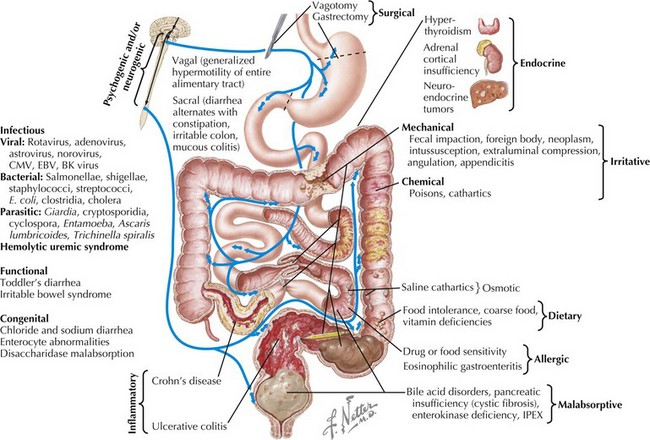

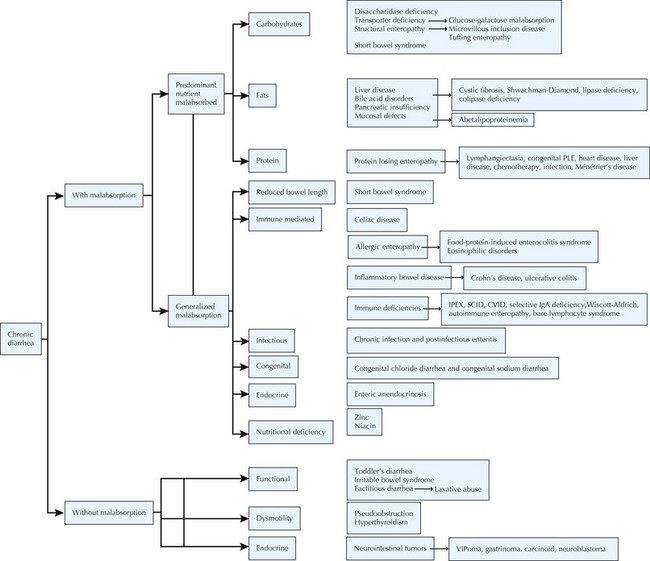

A total of 8 to 9 L of fluid enters the healthy intestines on a daily basis. Only 1 to 2 L are derived from food and liquid intake; the rest is from salivary, gastric, pancreatic, biliary, and intestinal secretions. Each day, about 90% of this fluid is absorbed in the small intestine, 1 L enters the colon, and about 100 mL is excreted in stool. Normal stool output is approximately 100 to 200 g/d. Diarrhea is defined as stool output greater than 200 g/d in children older than 2 years of age and greater than 10 mL/kg/d in children younger than 2 years of age. It is also described more practically as an increase in liquidity and frequency of bowel movements. Diarrhea can be categorized by duration, as either acute (≤2 weeks) or chronic (>2 weeks), or by mechanism, as osmotic or secretory. It can also be categorized by the presence or absence of malabsorption (Figure 111-1).

Acute Diarrhea

Etiology And Pathogenesis

The most common cause of acute diarrhea is infection (see Chapter 96). In young children, this is most often viral, with the most common agents being rotavirus, adenovirus, astrovirus, and norovirus. Norovirus causes 60% to 90% of nonbacterial gastroenteritis in the United States, affecting 23 million Americans each year. Rotavirus is a leading cause of death in children younger than 5 years of age worldwide. In immunocompromised hosts, viruses, including cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and BK virus, should be considered. It is estimated that 70% of infectious diarrhea is foodborne, and thus a detailed history of exposures is very important (Table 111-1). Exposure to untreated water may cause giardiasis. Use of public swimming pools poses a risk of Shigella, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Entamoeba infection, with the last three being chlorine resistant. Home pets can transmit infections. For example, turtles carry Salmonella spp. History of foreign travel may narrow exposures based on the specific destination. The most common etiology of traveler’s diarrhea remains enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. are responsible for most parasitic infections in developed countries. Cyclospora outbreaks have occurred in the United States. Clostridium difficile infection, previously thought to affect only hospitalized patients or those taking antibiotics, is now responsible for 40% of community-acquired diarrhea. A recent increase in C. difficile infections has been observed, some attributable to the resistant strain, BI/NAP1. An overgrowth of toxin-producing Clostridium organisms causes pseudomembranous colitis, which may be a potentially life-threatening condition. Vibrio cholerae remains a cause of illness and death in war zones and developing countries. The mechanism of infectious diarrhea is primarily secretory. It can quickly lead to electrolyte abnormalities and acidosis. Infection may result in villous atrophy, which can add an osmotic component. Mucosal healing after infection may lead to transient postinfectious diarrhea.

| Food | Associated Infectious Agent |

|---|---|

| Eggs | Salmonella |

| Dairy | Campylobacter jejunii |

| Vegetables | Clostridium perfringens |

| Pork | Clostridium perfringens Yersinia enterocolitica |

| Seafood | Aeromonas spp. Vibrio spp. Plesiomonas spp. |

| Rice | Bacillus cereus |

| Beef | Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli |

Several other causes of acute diarrhea, particularly in afebrile children, may be particularly concerning. Intussusception, a telescoping of two segments of bowel that occurs mostly in children between 6 months and 2 years of age, may present with bloody diarrhea (see Chapter 109). The typical presentation is colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, and an abdominal mass. “Currant jelly” stools do not occur in all patients with intussusception but are pathognomonic for the condition. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) is an uncommon but potentially fatal illness that may present with acute bloody diarrhea. HUS begins as a mild gastroenteritis that evolves into hematochezia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure (see Chapter 64). Less commonly, appendicitis may present with abdominal pain and diarrhea as a result of colonic irritation from the inflamed appendix (see Chapter 5).

Other acute causes of diarrhea include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; see Chapter 110), overfeeding (caused by increased osmotic loads), antibiotic-associated diarrhea (likely caused by changes in bowel flora), extraintestinal infections (otitis media, urinary tract infection, pneumonia), and toxic ingestions.

Chronic Diarrhea (Figure 111-2)

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Malabsorption of fat may also result in chronic diarrhea (Figure 111-3). Digestion of protein and fat begins in the oral cavity by salivary amylase and lipase and continues in the duodenum by pancreatic enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes are initially secreted as inactive proenzymes, which are activated by enterokinase, a brush border membrane protease. Enterokinase activates trypsinogen to its active form trypsin, which in turn activates the rest of the digestive enzymes. Lack of enterokinase, colipase, or lipase results in maldigestion of fats, failure to thrive, and steatorrhea. In cystic fibrosis, the secretion of pancreatic enzymes is diminished by hyperviscosity and mucous plugging of ducts. Bile acids participate in fat digestion and absorption by emulsifying long chain fatty acids, allowing them to form chylomicrons, which are then transported to the liver through lymphatics.

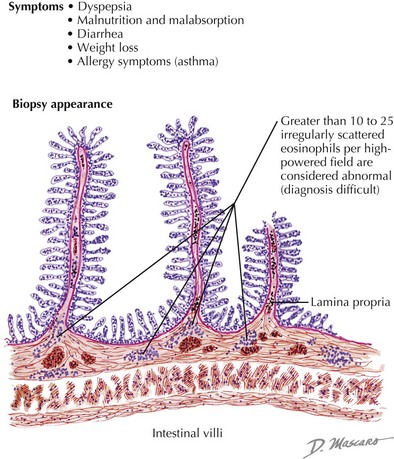

Several conditions causing chronic diarrhea are the result of an abnormal immune response to antigens in food or in the GI tract itself. Celiac disease is caused by gluten sensitivity, causing inflammation of the small intestine (see Figure 111-3). In celiac disease, exposure to gluten and its active component gliadin results in an abnormal immune activation. This dietary gluten-triggered immune process leads to villous blunting or flattening, crypt elongation, and lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propria. This disease affects about 1% of the population and can present any time between infancy and adulthood. It is associated with higher prevalence of HLA DQ2/DQ8; therefore, family history is important. It is also more common in the setting of Down’s syndrome, type 1 diabetes, IgA deficiency, Turner’s syndrome, William’s syndrome, and autoimmune thyroiditis. Chronic IBD, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, usually presents with slow-onset, sometimes bloody, diarrhea (see Chapter 110). Allergic colitis, which is often the result of milk or soy allergy, may present as bloody or nonbloody diarrhea in infants. Food allergies resulting in malabsorption may be caused by eosinophilic gastroenteritis (Figure 111-4). This disorder is often associated with multiple food proteins and other atopic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis. Mechanisms of eosinophilic disorders that are associated with eosinophilic infiltration of various parts of the GI tract are poorly understood. They seem to involve an interaction among genetic predisposition, environmental exposures to foods and allergens, immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated activation of the immune system, and possible interaction with GI microbiota. Rare immune deficiencies that cause diarrhea include IPEX syndrome, severe combined immune deficiency, and autoimmune enteropathy. IPEX syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FoxP3 gene in T-regulatory cells, resulting in a lack of immune homeostasis. Autoimmune enteropathy, which is associated with antienterocyte antibodies, may occur as part of IPEX but can also be isolated.

Clinical Presentation And Evaluation

Holtz LR, Neill MA, Tarr PI. Acute bloody diarrhea: a medical emergency for patients of all ages. Gastroenterol. 2009;136(6):1887-1898.

Pawlowski SW, Warren CA, Guerrannt R. Diagnosis and treatment of acute or persistent diarrhea. Gastroenterol. 2009;136(6):1874-1886.

Setty M, Hormaza L, Guandalini S. Celiac disease: risk assessment, diagnosis, and monitoring. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12(5):289-298.

Szajewska H, Setty M, Mrukowicz J, Guandalini S. Probiotics in gastrointestinal diseases in children: hard and not-so-hard evidence of efficacy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42(5):454-475.