CHAPTER 20 Diagnostic Wrist Arthroscopy

During the past 20 years, wrist arthroscopy has evolved into one of the most reliable and productive means of diagnosing, qualifying, and treating wrist pathology. As the arthroscopic surgeon’s instrumentation and technical ability improves, wrist arthroscopy is increasingly being presented as a necessary, routine, and safe procedure.1 Although it is a relatively new modality, it is an easily learned skill with ever-increasing indications.

An arthroscopic view allows excellent access to the articular surfaces of the carpal bones and ligaments that is not possible with arthrotomy.2 However, a thorough knowledge of wrist anatomy is essential for the safe arthroscopic identification and treatment of wrist pathology. This chapter emphasizes the standard elements of a diagnostic arthroscopic evaluation of the wrist.

ANATOMY

Two primary portals and two accessory portals have been described for use in the midcarpal space. The portal most commonly used for viewing is the radial midcarpal (RMC), which is located approximately 1 cm distal to the 3-4 radiocarpal portal and in line with the third metacarpal. The ulnar midcarpal portal is located on the midaxial line of the fourth metacarpal, approximately 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the 4-5 portal, enters the joint at the four-corner intersection between the lunate, triquetrum, hamate, and capitate. One of the two accessory portals is on the radial side of the midcarpal space and enters the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) joint. It is located just ulnar to the EPL tendon, at the level of the articular surface on the distal pole of the scaphoid. Staying on the ulnar side of this tendon usually maintains a safe margin between the portal and the radial artery at this level. Another accessory portal can be used, entering the triquetrohamate joint just ulnar to the ECU tendon, for a probe or instrument to access the joint or proximal pole of the hamate.3

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

The patient’s age and sex should be considered when evaluating a painful wrist. The young patient (<40 years) is more prone to post-traumatic carpal injuries, whereas the older patient is more susceptible to the late effects of systemic and degenerative processes. The patient’s medical history and the family medical history are helpful for diagnosing patients with many of the systemic and hereditary disorders that can manifest in the wrist. Laboratory values combined with this history is often helpful in this situation. Knowledge of the effect of the wrist pain on the patient’s daily activities, including work and leisure activities, is also essential for treatment planning.4

A systematic approach is essential for palpation of the wrist. All joints must be palpated and appropriately stressed with the use of some of the many provocative tests that have been described. Radially, carpometacarpal thumb arthritis can be assessed with the grind test. Just proximal to this, the STT joint should be palpated to assess for arthritis. Anatomic snuff box tenderness may indicate scaphoid or scapholunate ligament pathology. This ligament can be further assessed by Watson’s scaphoid shift test.5 The distal pole of the scaphoid is stabilized to restrict palmer flexion while the wrist is moved from ulnar to radial deviation. Dorsal wrist pain indicates subluxation of the scaphoid and scapholunate ligament instability. Ulnarly, lunotriquetral instability can be assessed by manipulating the two bones relative to each other (i.e., shear or ballottement test). Ulnocarpal abutment and triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears are tested by axial loading and ulnar wrist deviation. Pain just distal to the ulnar styloid and reproduction of symptoms with this maneuver indicate these conditions.

Instability of the midcarpal joint is suggested by the catch-up clunk, which is produced when the wrist is moved from radial to ulnar deviation during axial loading. The clunk is produced by sudden change in position of the proximal carpal row from a flexed position to an extended position as the triquetrum engages the hamate without the synchronizing effect of the attenuated ulnar ligaments. A painful response or crepitation on compressing the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) suggests instability or arthritic changes of the joint. Volarly, tenderness with palpation of the pisiform or hook of the hamate may represent pisotriquetral arthritis or hamate fracture, respectively.6

Diagnostic Imaging

Arthrography is useful to evaluate the integrity of capsular structures and interosseous ligaments, especially the scapholunate, lunotriquetral, and triangular fibrocartilage (TFC).2 It may show localized synovitis or abnormal leaks between normally compartmentalized spaces.

Computed tomography (CT) is useful to evaluate osseous and articular morphology. It is most effective in the evaluation of bone healing in the carpus after fracture or surgery, and CT can provide images in any plane needed (e.g., oblique axis of the scaphoid). Likewise, because fractures of the hook of the hamate are difficult to visualize with plain radiographs, CT provides clear detail to assist with decision making and treatment.6

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides important information about the soft tissues of the wrist and the vascularity of the bones. Avascular necrosis of the carpal bones, such as the lunate and scaphoid, and occult ganglions, soft tissue tumors, tendonitis, and joint effusions are well visualized using MRI. It is also the most accurate modality for evaluating bone bruises and microfractures. MRI has a sensitivity of 90% in evaluating the integrity of the TFCC. The accuracy of MRI for identifying tears of the scapholunate ligament has also approached 90%, but it drops significantly to 50% for lunotriquetral tears.6

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

Many forms of wrist pathology, such as cartilage flaps or tears of the (TFC), can be treated during arthroscopy.1 Wrist arthroscopy is a useful adjunct in the reduction of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius and percutaneous pinning of scaphoid fractures. Innovative surgeons have described partial carpal resections for post-traumatic arthritis and arthroscopically guided capitolunate fusions. Using the midcarpal, DRUJ, and volar portals has further expanded the arthroscope’s use as a tool for evaluation and treatment of midcarpal chondral lesions of the hamate, articular damage to the ulnar head or surrounding synovitis, and improved visualization of volar articular surfaces and dorsal capsular structures.7

Contraindications to wrist arthroscopy are limited mainly to conditions of trauma or swelling that distorts the normal anatomy or significantly damages capsular integrity, leading to fluid extravasation.

Arthroscopic Technique

Radiocarpal Evaluation

Diagnostic wrist arthroscopy begins with the 3-4 portal and is the primary viewing portal. Palpation and spinal needle localization of this portal are essential before the skin incision is made. Through the 3-4 portal, a needle is inserted, and the joint is distended with 5 to 7 mL of saline. The skin is incised with a no. 15 or 11 blade, and a small hemostat is used spread the soft tissues. Next, the blunt trocar should be inserted at approximately a 20-degree proximal angle to match the distal radius articular slope. This angle can avoid damaging the dorsal articular surface.2,8,9 Only blunt trocars are used in establishing portals. The inflow and outflow are interchangeable and can be maintained through the arthroscopic cannula or a separate 6-U portal established under direct arthroscopic visualization. We prefer the inflow through the arthroscope to push debris away instead of pulling it toward the camera. After a 3-4 portal is established, a diagnostic radiocarpal arthroscopy is performed.

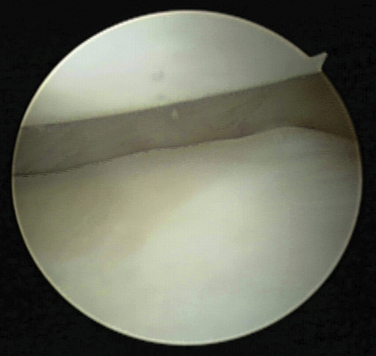

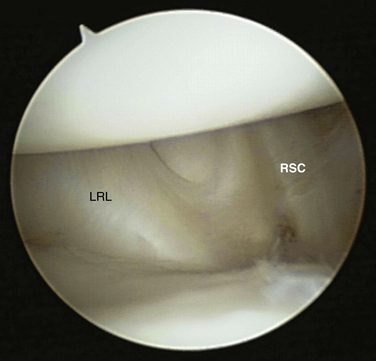

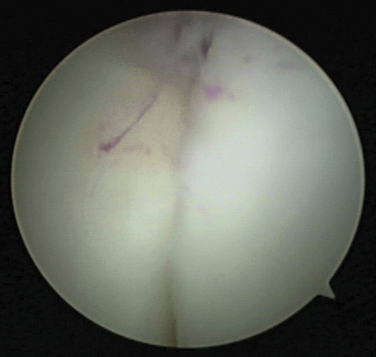

The radial styloid and radial capsule are examined first. The scaphoid superiorly and the radial styloid inferiorly can be evaluated for signs of arthritic change or articular injury (Fig. 20-1). The proximal border of the radial facet is examined, as are the volar extrinsic ligaments, the radioscaphocapitate ligament, and long radiolunate ligament (Fig. 20-2). The long radiolunate ligament is a wide structure usually two to three times the width of the radioscaphocapitate ligament.9,10 The ligaments should be taut on probing because of the traction applied to the wrist. Ulnar to these is the radioscapholunate ligament, also called the ligament of Testut, which is a vascularized tuft of tissue without any significant structural integrity. This tuft marks the scapholunate interval and sagittal ridge.10–12 Blood vessels are frequently seen along this ligament, and there is a natural redundancy to this ligament that should not be mistaken for a tear.

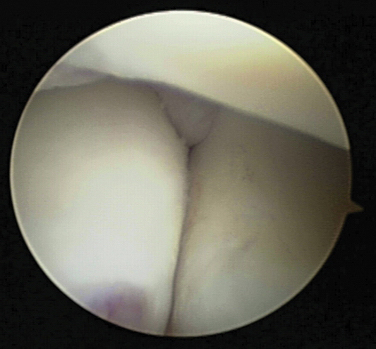

Following the scaphoid ulnarly, the slightly concave scapholunate interosseous ligament can be examined for tears or scapholunate diastasis (Fig. 20-3). An intact ligament may not be immediately obvious because it mimics the appearance of cartilage. Complete injury to this ligament, however, allows the arthroscope to pass between the scaphoid and the lunate (i.e., drive-through sign).2

The proximal surface of the lunate and the distal surface of the radius can be evaluated next. The two fossae of the distal radius, the scaphoid and the lunate fossae, are separated by a sagittal ridge. Fraying or fissuring of this area, suggestive of chondromalacia, should be documented. Normally, in the neutral wrist position, one half of the lunate articulates with the lunate facet, and one half articulates with the TFC.10

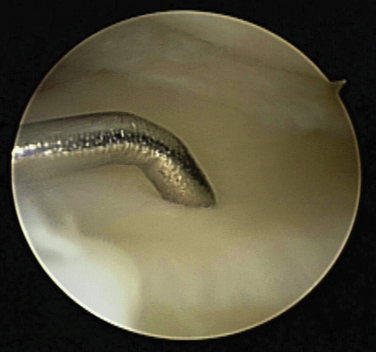

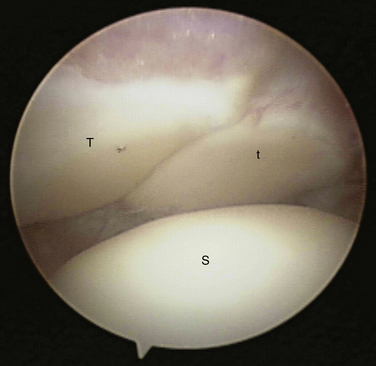

The radial attachment of the TFC is evaluated, as are the volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments. The lunotriquetral interosseous ligament is evaluated by identifying a sulcus or concavity in the otherwise convex articular surfaces of the lunate and triquetrum.13 A probe can be inserted through the 4-5 or 6-R portal to evaluate the integrity of the lunotriquetral ligament. Next, the peripheral attachment of the TFC and the ulnar prestyloid recess should be examined. The TFC is wedge shaped in the coronal plane, with a thickened periphery and a thin radial attachment.12 A probe can be used to evaluate the tension of the TFCC by ballottement (i.e., trampoline test) (Fig. 20-4).11,13 The TFC, also known as the articular disk, should be taut, and lack of tension raises suspicion of a central or peripheral TFCC tear. The peripheral 15% to 20% of the TFCC is vascularized and therefore has healing potential if torn.2 The prestyloid ulnar recess is a normal anatomic finding that is approximately 3 to 4 mm wide, and it should not be mistaken for a peripheral tear.10 The ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments may be more easily evaluated by placing the arthroscope in the 4-5 or 6-R portal. These ligaments are identified as capsular thickenings in the volar aspect of the ulnar capsule.

Midcarpal Evaluation

After a complete examination of the radiocarpal joint has been performed, the arthroscope can be used to evaluate the midcarpal space. The radial midcarpal portal, located approximately 1 cm distal to the 3-4 radiocarpal portal, is typically used to establish a diagnostic arthroscopy portal. The midcarpal joint can be distended with 3 to 5 mL of fluid through any of the portals. This allows easier access into the joint with a blunt trocar and minimizes the risk of damaging the articular cartilage.10 Normally, there is no communication between the radiocarpal and midcarpal spaces.3

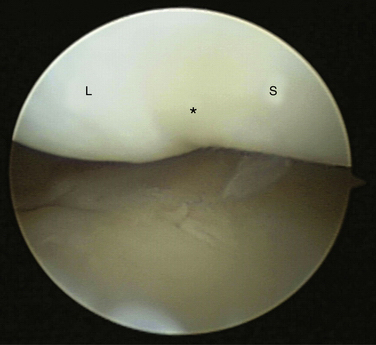

Care must be taken when entering the radial midcarpal space, because it is less than one half of the depth of the radiocarpal space.2 The ulnar midcarpal portal is created for instrumentation and visualization of the ulnar portion of the midcarpal joint. The arthroscopic evaluation in this area begins with visualization of the convexity of the capitate (superiorly) and the scapholunate joint (inferiorly). The scapholunate joint should be perfectly congruous (Fig. 20-5). The scapholunate ligament is not present on the distal edge of the scapholunate joint, and the joint is best viewed from this perspective. Intraoperatively, the stability of the joint may be assessed by performing Watson’s scaphoid shift test.3,14

The distal surfaces of the lunate and the triquetrum are then evaluated, as is the concave proximal surface of the hamate (Fig. 20-6). The lunotriquetral joint is also well visualized from this view, and a ballottement test can be performed to assess stability. Within the distal row, the capitate and capitohamate articulation can be examined from this portal. Farther ulnarly, the triquetrohamate joint may be used to establish an accessory portal. The triquetrohamate joint is a saddle-shaped joint that is normally quite tight and difficult to view across unless pathologic laxity exists.3

The STT joint can be seen by passing the arthroscope radially, and early osteoarthritic changes, common in this area, should be identified.15 In the STT joint, the trapezoid is in the foreground, and the trapezium is in the background (Fig. 20-7). Bubbles frequently collect here and may impair visualization of the joint. These bubbles may be evacuated with a 21-guage needle, and débridement can be performed with a small, motorized shaver through an accessory STT portal.3

Distal Radioulnar Joint Evaluation

On completion of the diagnostic midcarpal arthroscopy, a proximal distal radial ulnar joint portal can be established, and the ulnar surface of the radius, the radial surface of the ulna, the distal surface of the ulnar head, and the proximal surface of the TFCC can be evaluated. DRUJ arthroscopy is performed with the forearm in supination and suspended in the wrist traction device but without any traction applied. A blunt trocar is angled slightly distal and placed in the joint. If required, outflow can be created by placing an 18-gauge needle into the distal portion of the joint. Through pronation and supination of the wrist, the articular margin of the ulna can be passed in front of the arthroscope lens. This approach is useful for lysis of adhesions, débridement, exostectomy, or capsulotomy of the DRUJ.2,16

CONCLUSIONS

Arthroscopy of the wrist has become a commonly employed technique for the evaluation and treatment of intra-articular wrist disorders. It enables evaluation of the intercarpal structures under bright, magnified conditions with minimal morbidity compared with arthrotomy.9 A systematic approach combined with a thorough knowledge of wrist anatomy allows the surgeon to optimize the probability of a successful outcome while minimizing the potential for complications of wrist arthroscopy.

1. Sennwald G. Diagnostic arthroscopy: indications and interpretations of findings. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:241-246.

2. Geissler WB. Wrist Arthroscopy. New York, NY: Springer, 2005. 1-13

3. Viegas SF. Midcarpal arthroscopy; anatomy and portals. Hand Clin. 1994;10:577-587.

4. Brown DE, Lichtman DN. The evaluation of chronic wrist pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1984;15:184.

5. Watson HK, Ashmead DIV, Makhlouf MV. Examination of the scaphoid. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:657-660.

6. Nagle DJ. Evaluation of chronic wrist pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:45-55.

7. Slutsky DJ. Wrist arthroscopy portals, volar and dorsal.. In: Trumble TE, Budoff JE, eds. Master Skills: Wrist and Elbow Arthroscopy Reconstruction. Rosemont, IL: American Society of Surgery of the Hand; 2006:31-46.

8. Roth JH. Radiocarpal arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 1988;11:1309-1312.

9. Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Weiss AP, et al. Techniques in wrist arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1184-1197.

10. Bettinger PC, Cooney WP3rd, Berger RA. Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:707-719.

11. North ER, Thomas S. An anatomic guide for arthroscopic visualization of the wrist capsular ligaments. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:815-822.

12. Roth JH, Poehling GG, Whipple TL. Arthroscopic surgery of the wrist. Instr Course Lect. 1988;37:183-194.

13. Berger RA. Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist and distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clin. 1999;15:393-413. vii

14. Hofmeister EP, Dao KD, Glowacki KA. The role of midcarpal arthroscopy in the diagnosis of disorders of the wrist. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26:407-414.

15. Viegas SF. Advances in skeletal anatomy of the wrist [review]. Hand Clin. 2001;17:1-11. v

16. Whipple TL, Cooney WP3rd, Osterman AL, et al. Wrist arthroscopy. Instr Course Lect. 1995;44:139-145.