Chapter 74 Diagnostic Thoracic Surgical Procedures

Clinical Application of Diagnostic Thoracic Procedures

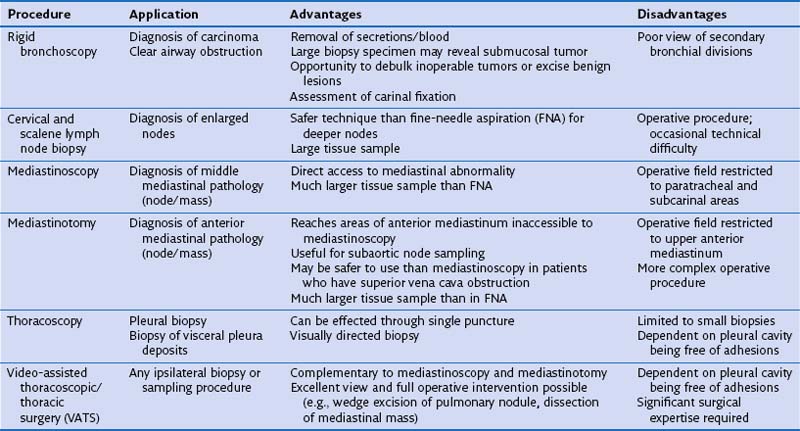

The diagnostic thoracic surgical procedures discussed in this chapter have varied applications, with relative advantages and disadvantages (Table 74-1) and are typically used in the following three broad areas:

• Assessment of bronchogenic carcinoma

• Diagnosis of interstitial lung disease

• Sampling of indeterminate pleural, pulmonary, and mediastinal lesions

Rigid Bronchoscopy

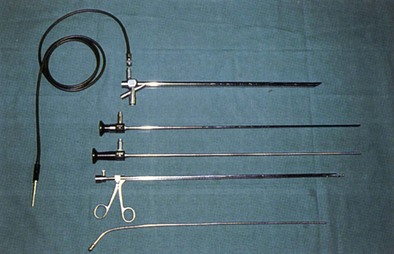

Rigid bronchoscopy is mostly used for therapeutic airway interventions such as airway dilation, laser debridement, tumor debulking, placement of airway stents, or foreign body retrieval (Figure 74-1). The use of the rigid bronchoscope continues to be an important diagnostic tool in special circumstances, such as those requiring a better tactile sense when assessing for possible extrinsic tumor invasion of the airway, or when larger biopsies are sought. It is also indispensable when airway control is in question because of hemoptysis or tumor invasion.

Technique

The bronchoscope is inserted through the right side of the patient’s mouth with the bevel down (Figure 74-2). It is advanced toward the base of the tongue in the posterior oropharynx. The tip of the epiglottis is then identified by carefully elevating the tongue as the scope is brought more into a horizontal position. The scope is then advanced a short distance past the tip of the epiglottis. The protruding superior lip of the bronchoscope is then used to lift gently the tip of the epiglottis, allowing visualization of the vocal cords and laryngeal inlet. The surgeon will then rotate the bronchoscope 90 degrees along its long axis, placing the bevel in the anteroposterior plane to allow easy passage through the vocal cords. The bronchoscope can then be carefully advanced into the trachea under direct vision. To facilitate passage of the bronchoscope into the left or right main stem bronchus, the patient’s head is turned to the contralateral side. Visualization of the segmental and subsegmental airways can be facilitated by insertion of a flexible bronchoscope through the lumen of the rigid bronchoscope.

Cervical Mediastinoscopy

Technique

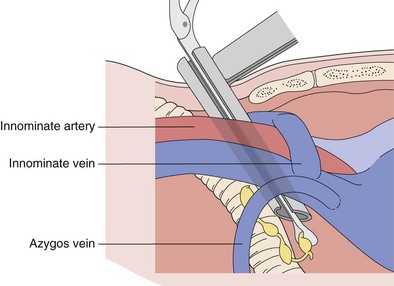

With the patient intubated and under general anesthesia, a bolster is placed under the shoulders to provide adequate neck extension for the procedure. A 2.5-cm transverse incision is made approximately 1 cm above the sternal notch. The pretracheal fascia is exposed by splitting the strap muscles in the midline, with right-angle retractors used to retract the thyroid gland superiorly if necessary. The pretracheal fascia is incised transversely and bluntly dissected off the anterior surface of the trachea with the index finger. This allows direct palpation of the vascular structures, including the aortic arch and innominate vessels, as well as any prominent lymphadenopathy. The mediastinoscope is introduced beneath the pretracheal fascia (Figure 74-3). Further blunt dissection can be done under direct vision using the tip of the mediastinoscopy sucker. Systematic dissection and biopsy of the different lymph node levels are then possible.

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

Technique

Thoracoscopy is performed by use of single-lung ventilation of the contralateral side. The patient is positioned in the lateral position similar to the positioning used for a posterolateral thoracotomy. When VATS is done for drainage and evaluation of a pleural effusion, a single 1-cm port is usually sufficient. It is placed in the sixth or seventh interspace in the anterior axillary line. Through this port, the camera and a thin suction tip or biopsy forceps can be introduced and maneuvered. For most other applications, one or two additional 1-cm ports are required, usually positioned separately along the fourth or fifth interspace, in the line of a potential posterolateral thoracotomy (Figure 74-4). In this way, conversion to thoracotomy simply requires extending the incision between these two upper port sites. The anterior port can be converted to a 5-cm to 7-cm “access” port for removal of a lobectomy specimen, if the procedure requires conversion to a VATS lobectomy, in the case of a biopsied lung nodule found to be an invasive primary lung cancer.

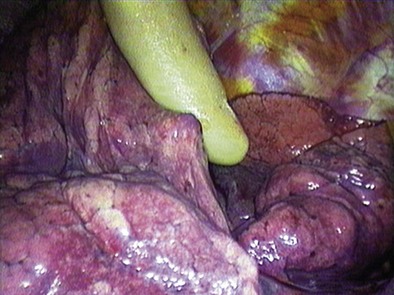

Whereas biopsy for diagnosis of ILD requires only defining several areas of representative pathology, wedge resection of an indeterminate pulmonary nodule first necessitates precise localization of the lesion. This is usually done with the surgeon’s finger introduced through one of the thoracoscopy incisions (Figure 74-5). It is clearly easier to locate larger and peripherally located lesions. Smaller or deeper lesions may not be accessible and may require conversion to open thoracotomy. In general, a pulmonary nodule can be palpated during a VATS exploration if the diameter of the lesion is greater than the depth of lung tissue through which it is felt. Recent experience has been initially promising with radiotracer guidance (technetium 99m) to locate small pulmonary lesions not otherwise discernible thoracoscopically.

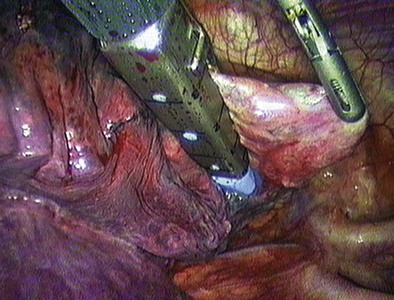

Once the area to be biopsied has been located, an endoscopic stapling device can be inserted through a thoracoport and used to perform a wedge resection (Figure 74-6). Once the specimen has been resected, it should be removed from the pleural cavity within an endoscopic specimen retrieval bag to avoid port site contamination. A more economical alternative is to use a surgical glove introduced through one of the port sites and held open with two Kelly clamps.

Allen MS, Deschamps C, Jones DM, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgical procedures: the Mayo experience. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1996;71:351–359.

Annema JT, van Meerbeeck JP, Rintoul RC, et al. Mediastinoscopy vs. endoscopy for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:2245–2252.

Catarino PA, Goldstraw P. The future in diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Respiration. 2006;73:717–732.

Ginsberg RJ, Rice TW, Goldberg M, et al. Extended cervical mediastinoscopy: a single staging procedure for bronchogenic carcinoma of the left upper lobe. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:673–678.

Hammoud ZT, Anderson RC, Meyers BF, et al. The current role of mediastinoscopy in the evaluation of thoracic disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:894–899.

Kuzdzal J, Zielinski M, Papla B, et al. The transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy versus cervical mediastinoscopy in non–small cell lung cancer staging. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:88–94.

Leschber G, Holinka G, Linder A. Video-assisted mediastinoscopic lymphadenectomy (VAMLA): a method for systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:192–195.

Nechala P, Graham AJ, McFadden SD, et al. Retrospective analysis of the clinical performance of anterior mediastinotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:2004–2009.

Stiles BM, Altes TA, Jones DR, et al. Clinical experience with radiotracer-guided thoracoscopic biopsy of small, indeterminate lung nodules. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1191–1197.

Temes RT, Joste NE, Qualls CR, et al. Lung biopsy: is it necessary? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:1097–1100.

Yasufuku K, Pierre A, Darling G, et al. A prospective controlled trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration compared with mediastinoscopy for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:1393–1400.