Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Standard Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed at the beginning of all endoscopic procedures; therefore a systematic evaluation of the peritoneal cavity should be performed. This is especially important prior to laparoscopic management of an adnexal mass.

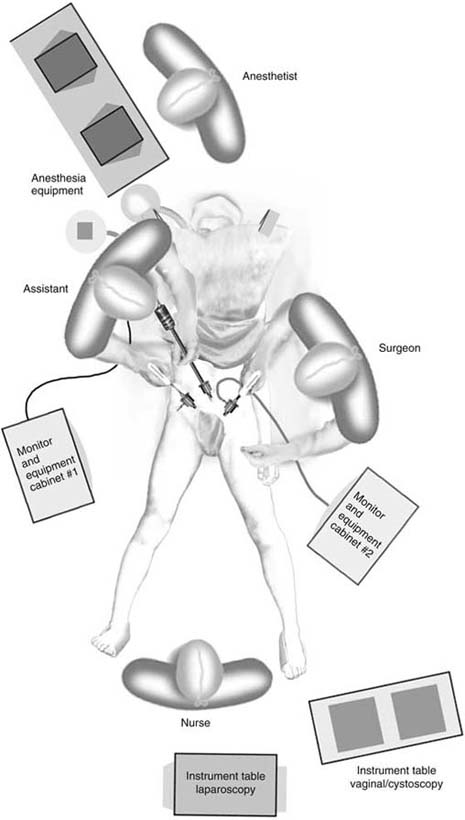

Generally, a right-handed surgeon should stand to the left of the patient (Fig. 116–1). The assistant stands on the right, and the scrub nurse or technician stands in between the legs. After insertion of the primary trocars, the patient is placed in Trendelenburg’s position, and the peritoneal cavity is inspected to confirm that there is no contraindication to a laparoscopic procedure. If excrescences appear on the peritoneal surfaces or if an adnexal mass is present that is suspicious for malignancy, a laparotomy should be performed. If there is any active bleeding that is not clearly identified and easily controlled, a laparotomy should be performed.

It is difficult to perform a complete diagnostic evaluation without an accessory port. A suprapubic site is adequate for most diagnostic pelvic procedures. A suggested order of evaluation is:

Panoramic view of the pelvis (Fig. 116–2)

Panoramic view of the pelvis (Fig. 116–2)

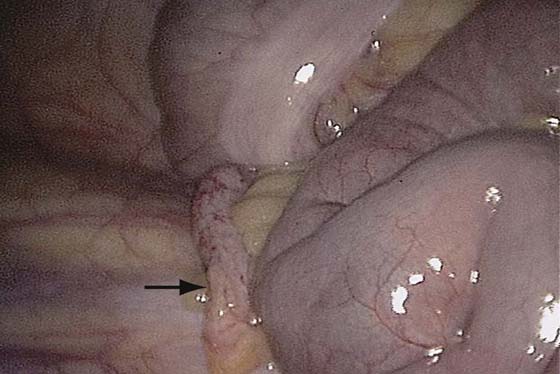

Cecum, appendix, and ascending colon (Fig. 116–3)

Cecum, appendix, and ascending colon (Fig. 116–3)

Liver, gallbladder, and right hemidiaphragm (Fig. 116–4)

Liver, gallbladder, and right hemidiaphragm (Fig. 116–4)

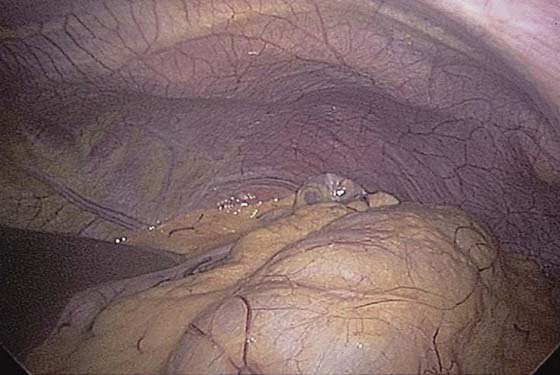

Transverse colon, omentum, small bowel, and peritoneal surfaces (Fig. 116–5)

Transverse colon, omentum, small bowel, and peritoneal surfaces (Fig. 116–5)

Stomach, left hemidiaphragm, and descending colon and spleen (Fig. 116–6)

Stomach, left hemidiaphragm, and descending colon and spleen (Fig. 116–6)

Sigmoid and rectum (Fig. 116–7)

Sigmoid and rectum (Fig. 116–7)

The spleen usually is not seen except in thin women or when traction is placed on the omentum.

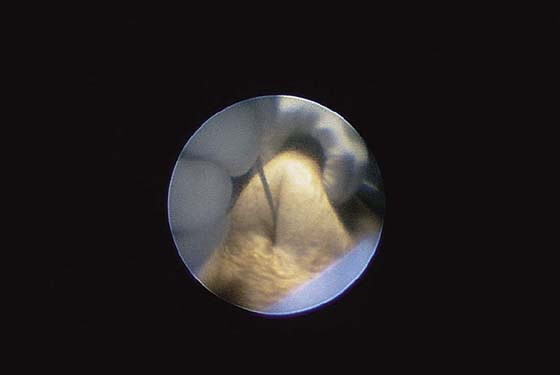

A detailed view of the pelvic organs is obtained. A probe should be used to lift the ovaries so that a view of the ovarian fossa is obtained as well (Fig. 116–8).

FIGURE 116–1 Personnel placement during diagnostic laparoscopy.

FIGURE 116–2 Panoramic view of the pelvis.

FIGURE 116–3 Cecum, appendix (arrow), and ascending colon.

FIGURE 116–4 Liver, gallbladder, and right hemidiaphragm.

FIGURE 116–5 Transverse colon, omentum, small bowel, and peritoneal surfaces.

FIGURE 116–6 Stomach, left hemidiaphragm, and descending colon; the spleen usually is not seen except in thin women or when traction is placed on the omentum. In this patient, the tip of the spleen is seen.

FIGURE 116–7 An atraumatic clamp grasps the fat around the sigmoid colon.

FIGURE 116–8 A probe should be used to lift the ovaries to obtain a view of the ovarian fossa. An endometriotic lesion can be seen on the peritoneum, and a paratubal cyst on the fallopian tube. The ureter can be identified transperitoneally.

Microlaparoscopy

The evolution of surgery toward a more minimally invasive approach has promoted technology that emphasizes smaller-caliber instruments. Microlaparoscopy refers to some of the applications of this technology; the most widely used of these is for diagnostic procedures, especially for infertility and chronic pelvic pain. These procedures can be performed with the patient under local anesthesia or conscious sedation.

Instruments used for this procedure range from 1.3 to 4 mm in diameter. The diagnostic accuracy of these smaller laparoscopes has received mixed reviews. A 5-mm laparoscope was found to give the best visualization. If this procedure is performed in an office setting, then a thorough knowledge of local anesthetic agents and sedatives is mandatory. We currently perform this procedure in an operating room setting with an anesthesiologist administering the sedation. The patient is conscious throughout the procedure. The following steps are required:

The patient applies a local anesthetic cream (like EMLA cream) to the umbilical and suprapubic areas 2 hours before surgery.

The patient applies a local anesthetic cream (like EMLA cream) to the umbilical and suprapubic areas 2 hours before surgery.

The patient empties her bladder before coming into the room.

The patient empties her bladder before coming into the room.

Intravenous access is obtained.

Intravenous access is obtained.

The patient is brought into a procedure/operating room. The lights are dimmed.

The patient is brought into a procedure/operating room. The lights are dimmed.

The abdomen and the vagina are prepared and draped in the usual manner.

The abdomen and the vagina are prepared and draped in the usual manner.

A paracervical block is performed, and a uterine manipulator is inserted.

A paracervical block is performed, and a uterine manipulator is inserted.

Local anesthesia is infiltrated in the umbilical area.

Local anesthesia is infiltrated in the umbilical area.

The abdominal wall is elevated, and the primary trocar is inserted (Fig. 116–9).

The abdominal wall is elevated, and the primary trocar is inserted (Fig. 116–9).

Insufflation is performed so as to maintain an adequate field. In this way, the carbon dioxide (CO2) is insufflated with a pressure range of 15 mm Hg but is turned on and off to establish and maintain the appropriate visual field (Fig. 116–10).

Insufflation is performed so as to maintain an adequate field. In this way, the carbon dioxide (CO2) is insufflated with a pressure range of 15 mm Hg but is turned on and off to establish and maintain the appropriate visual field (Fig. 116–10).

FIGURE 116–9 The abdomen is elevated and a 2-mm introducer (Autosuture MiniPort Disposable Introducer, US Surgical, Norwalk, Connecticut) is inserted.

FIGURE 116–10 View of the pelvis from a 2-mm laparoscope (Autosuture).

Mark D. Walters

Mark D. Walters