CHAPTER 2 Diagnostic Elbow Arthroscopy and Loose Body Removal

Advances in elbow arthroscopy have enabled surgeons to treat a broad spectrum of disorders that were once thought to be unsafe using arthroscopic techniques.1 Although technically demanding, advances in surgical technique and arthroscopic equipment and an improved understanding of neurovascular and joint anatomy have made this procedure safer and more effective than its initial applications.

The indications for elbow arthroscopy continue to evolve. In previous years, elbow arthroscopy was mainly used for removal of loose bodies,2–8 synovectomy,9,10 lysis of adhesions,11,12 excision of osteophytes,13,14 débridement of osteochondritis dissecans lesions,6,15–17 radial head resection,18 plica excision,19,20 instability,21 septic arthritis,22 and diagnostic arthroscopy for complex elbow pain.6 These indications have been expanded to include débridement, drilling, and autograft replacement for osteochondritis dissecans; débridement and repair of lateral epicondylitis; and débridement of radiocapitellar arthritis, olecranon bursectomy, arthrofibrosis, and fractures of the radial head, capitellum, and distal humerus.6,8,9,23

Removal of loose bodies is perhaps the most common and rewarding arthroscopic procedure involving the elbow.4,24,25 Arthroscopic identification and removal of such impediments to joint motion has significant advantages. Scar formation is limited by the small portal site incisions needed to fully evaluate and perform loose body removal. All compartments of the elbow are readily accessible for a thorough evaluation of intra-articular pathology with the arthroscope.

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

A careful history, physical examination, and appropriate imaging are imperative before arthroscopic excision of loose bodies and osteophytes within the elbow joint. On presentation, patients with loose bodies often complain of pain, stiffness, catching, clicking, and locking of the elbow joint. Physical examination findings often include sometimes subtle losses of flexion, extension, and a small effusion that can be detected most often in the posterolateral gutter.26

When preparing for arthroscopic loose body excision, a detailed history of past surgical ulnar nerve neurolysis or transposition, along with physical examination for subluxation of the ulnar nerve, cannot be overemphasized. A subluxated or dislocated ulnar nerve can be found in 16% of the normal population.26 Awareness of these variations in normal anatomy is essential to prevent iatrogenic neural injury.

Diagnostic Imaging

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the elbow should be routinely obtained (Fig. 2-1). However, standard imaging fails to demonstrate almost 30% of loose bodies, and in such cases, further diagnostic testing, such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, may be warranted.4,5,26,27 In most cases, loose bodies are found in the coronoid fossa, olecranon fossa, and posterior aspect of the lateral gutter. Although careful attention must be paid to these areas, loose bodies often migrate and may be difficult to see on imaging. In some cases, arthroscopic evaluation may prove to be the gold standard for demonstrating loose bodies when classic presentations are encountered.26

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

Patients who have failed conservative management for loose bodies within the elbow are candidates for elbow arthroscopy and loose body removal. However, before surgical intervention is undertaken, the treating surgeon must ascertain the cause of these impediments to normal joint motion. Loose bodies may be the result of osteochondritis dissecans, degenerative arthritis, synovial chondromatosis, or trauma.4,5,28 A carefully formulated plan to address the primary underlying pathology at the time of surgery can prevent the future formation of loose bodies.28

Absolute contraindications to elbow arthroscopy include any variation in the normal bony or soft tissue anatomy that precludes the safe insertion of the arthroscope into the elbow joint.28 Other contraindications include an ankylosed elbow joint that would preclude joint distention and local soft tissue infection in the area of portal sites. Prior ulnar nerve transposition is a relative contraindication if it interferes with portal positioning.28 However, elbow arthroscopy can be used if the ulnar nerve is identified with surgical dissection before portal creation.

Elbow Arthroscopy

Anesthesia

General anesthesia or regional blocks are the most common methods used in elbow arthroscopy. General anesthesia is more commonly used because of the flexibility it permits with respect to patient positioning and postoperative examination. The prone and lateral decubitus positions are poorly tolerated in awake patients, and these positioning methods are most amenable to general anesthesia.12 Use of general anesthesia in the absence of a neurologic block enables immediate postoperative neurologic examination.

Patient Positioning

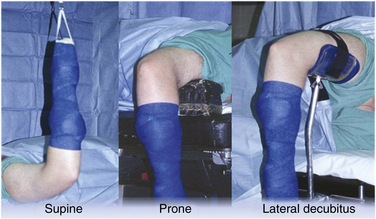

Supine Position.

Supine positioning for elbow arthroscopy was first described in 1985.9 After supine positioning of the patient on the operating table, the operative extremity is lateralized on the operating table so that the shoulder is placed at the edge of the bed. The patient is secured, and all pertinent prominences are appropriately padded. The operative extremity is placed in 90 degrees of shoulder abduction, 90 degrees of elbow flexion, and neutral forearm rotation, and a nonsterile arm tourniquet is applied (Fig. 2-2). Traction is facilitated with the use of a traction device.

The supine position offers several advantages to the elbow arthroscopist.2 A three-dimensional understanding and application of elbow anatomy is facilitated by the anatomic and familiar position of the elbow. This also benefits the surgeon if open procedures follow. This position enables quick access to the patient’s airway and the choice of multiple effective anesthetic regimens. Drawbacks of the supine position include the necessity of a traction setup, which makes manipulating the elbow cumbersome, and the inability to easily visualize and work in the posterior compartment.

Prone Position.

The prone position was first described in 1989 as an alternative method for positioning.29 The aims of this method were to improve access to the posterior compartment of the elbow and eliminate the need for a traction device for intraoperative elbow manipulation.

The patient is initially intubated on a gurney and rolled to the prone position on the operating table. The face and chest are padded and supported by a foam airway and head positioner and by padded chest rolls. The nonoperative extremity is brought into 90 degrees of shoulder abduction and neutral rotation with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion. The elbow and wrist are supported by a padded arm board. On the operative side, an arm board is placed parallel to the operating table centered at the shoulder level. A nonsterile arm tourniquet is applied, and the arm is placed in 90 degrees of shoulder abduction and neutral rotation. The arm is supported at the middle humeral level by a padded bolster attached the operating table or by a rolled towel bump that is positioned on top of the arm board, which suspends the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion (see Fig. 2-2).

The prone position has several advantages. With the arm freely hanging, the elbow is easily manipulated from flexion to full extension. This can be done without the use of a traction setup or arm positioner and without an assistant. The posterior compartment of the elbow is easily accessible. Flexion of the elbow allows the neurovascular structures to sag anteriorly, providing a greater margin of error when establishing anterior portal sites. As with the supine position, open procedures are easily conducted on the medial and lateral sides of the elbow if necessary.30

Lateral Decubitus Position.

The lateral decubitus position was described by O’Driscoll and Morrey in 1993.30 The aim of this position was to exploit the benefits of the supine and prone positions while avoiding the major pitfalls inherent to each setup. The patient is initially placed in the lateral decubitus position with the aid of a bean bag or sand bag kidney rests and secure taping or strapping. An axillary roll is appropriately placed. The operative extremity is positioned over an arm holder or over a padded bolster, with the shoulder internally rotated and flexed to 90 degrees. The elbow is maintained in 90 degrees of flexion (see Fig. 2-2).

Arthroscopic Portals

At the outset of any elbow arthroscopic procedure, various landmarks must be localized and marked. The ulnar nerve, radial head, olecranon, lateral epicondyle, and medial epicondyle should be traced with a marking pen. Palpating and outlining the course of the ulnar nerve cannot be overemphasized to ensure that it is not subluxated or subluxatable. An 18-gauge spinal needle is used to insufflate the elbow joint with approximately 20 to 30 mL of sterile saline. This can be accomplished through a posterior injection into the olecranon fossa or through the lateral soft spot portal site, which is bounded by the radial head, lateral epicondyle, and olecranon (Fig. 2-3). The intra-articular injection can be confirmed by resistance to further inflow and often by the slight extension of the elbow seen as fluid is introduced. Distention of the joint capsule further protects the anterior neurovascular structures by displacing them anteriorly and farther away from planned portal sites.32,33

Proximal Anteromedial Portal.

The proximal anteromedial portal was first described in 1989 and has been recommended as the initial portal for elbow arthroscopy in the prone and lateral decubitus positions.32,34 Initial creation of this portal is suggested because it provides the best view of intra-articular structures and is less likely than the anterolateral portal to be affected by extravasation.32 This portal provides visualization of the anterior elbow joint structures, including the anterior capsule, coronoid process, trochlea, radial head, capitellum, and medial and lateral gutters.

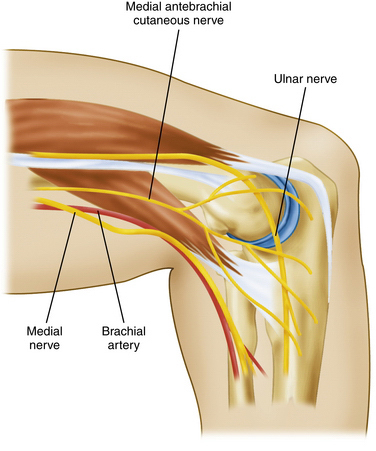

The proximal anteromedial portal is made approximately 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and just anterior to the intermuscular septum (Fig. 2-4). Placement anterior to the medial intermuscular septum avoids injury to the ulnar nerve, which courses posterior to this structure at this level. A blunt trocar is introduced through a nick in the skin (alternatively, a nick and spread technique can be employed with a small hemostat before trocar entry) and advanced distally along the anterior edge humerus toward the radiocapitellar joint. Maintaining contact with the humeral cortex during trocar advancement allows the brachialis muscle to serve as a partition between the trocar and anterior neurovascular structures. The trocar enters the elbow through the tendinous origin of the flexor-pronator group and medial capsule.35

Relative contraindications to creation of this portal include ulnar nerve subluxation or previous ulnar nerve transposition.32,36,37 This portal can be used if care is taken to identify the course of the nerve with dissection before trocar placement. In the absence of ulnar nerve subluxation or a history of transposition, the ulnar nerve is located between 12 and 23.7 mm from the portal site, and it is not at risk as long as the trocar entry site is placed anterior to the intermuscular septum.32,37

The main structure at risk during creation of this portal site is the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve as it courses approximately 2.3 mm from the entry site (see Fig. 2-4). The median nerve is at risk as the trocar is advanced distally between the humerus and brachialis muscle. The average distance from the trocar tip is 12.4 to 22 mm.32,37

Anteromedial Portal.

The anteromedial portal, which is positioned 2 cm distal to and 2 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle, was originally described in 1985.9 This portal can be established with an outside-in or inside-out technique.32 The outside-in technique is accomplished by passing the blunt trocar toward the center of the joint while remaining in the plane between the humerus and brachialis muscle. The trocar tip is advanced through the flexor-pronator origin and into the joint at a position anterior to the medial collateral ligament.

The main structure at risk during creation of the anteromedial portal site is the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which lies within 1 to 2 mm from the portal site.37 The median nerve travels approximately 7 to 14 mm away from the portal site.33,37 The safe distance between the trocar and nerve can be increased to 22 mm if the portal site is moved to 1 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle.32

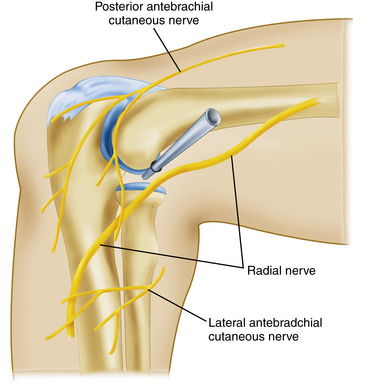

Proximal Anterolateral Portal.

The proximal anterolateral portal has been described by several surgeons27,37,38 and is positioned approximately 2 cm proximal to and 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 2-5). It can be established as the initial portal in elbow arthroscopy. As the trocar is advanced distally toward the elbow joint, the brachioradialis and brachialis muscle are pierced before entering the lateral joint capsule. With the arthroscope placed into the cannula, the anterior capsule, lateral gutter, radial head, capitellum, coronoid, and anterolateral aspect of the ulnohumeral articulation can be visualized.

Two neural structures are at risk with the creation of the proximal anterolateral portal. The development of the proximal anterolateral portal site was in response to the relative proximity of the radial nerve to the standard anterolateral portal (see Fig. 2-5). Anatomic studies with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion and distended with fluid at the time of proximal anterolateral portal creation reveal a safe distance of 9.9 to 14.2 mm between the trocar and radial nerve.37,38 This distance is markedly decreased to 4.9 to 9.1 mm when the standard anterolateral portal is created.37,38 Cutaneous sensation in the forearm can likewise be disrupted if the posterior branch of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is injured. The pathway of this portal site is an average of 6.1 mm from this sensory nerve.37

Anterolateral Portal.

The standard anterolateral portal, created 3 cm distal to and 1 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle, was first described in 1985.9 As the blunt trocar is introduced, it passes through the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle before transversing the lateral joint capsule. This portal position is limited in its capabilities with respect to the lateral joint. However, it permits visualization of the anteromedial aspect of the joint, including the trochlea, coronoid fossa, coronoid process, and medial aspect of the radial head.38 In conjunction with the proximal anterolateral portal, the standard anterolateral portal can be used for procedures involving the radial head and annular ligament.

As with the anteromedial portal, the anterolateral portal site can be established with an inside-out technique. This can be accomplished with the aid of a proximal anteromedial or anteromedial viewing portal. In either case, the arthroscope tip is advanced to the capsule lateral to the radial head and held in this position as the arthroscope is removed from the cannula. A blunt switching stick is then placed in the cannula and forced through the capsule. The overlying tented skin is incised, the rod is advanced, and a cannula is introduced in a retrograde fashion to create the anterolateral portal. Care must be taken to place the portal site lateral to the radial head, because moving anterior to this position puts the radial nerve in jeopardy of injury.32,35,37

The primary structures at risk with creation of the standard anterolateral portal include the posterior antebrachial cutaneous and radial nerves. The distance of the portal site to these vital structures is approximately 2 mm and between 4.9 and 9.1 mm, respectively.33,37,38 A more proximal anterolateral portal site risks radial nerve injury.

Midlateral Portal.

The midlateral portal is relatively safe with respect to neurovascular structures, and the sole risk is injury to the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which courses approximately 7 mm away.39 Caveats to creation of this portal center on the propensity for soft tissue fluid extravasation and the risk of iatrogenic articular cartilage damage due to the limited space available.36,37,40

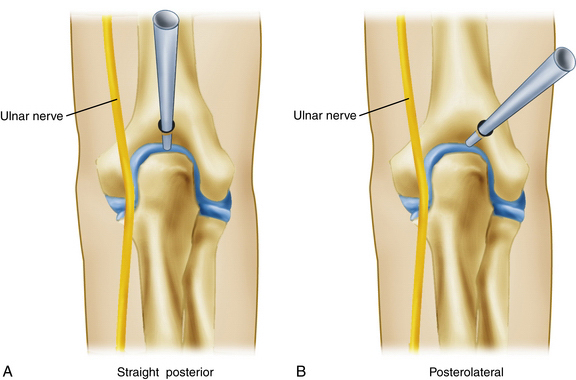

Straight Posterior Portal.

The straight posterior portal breeches the central midsubstance of the triceps tendon and is located 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon in the midline (Fig. 2-6). In this position, the entire posterior compartment can be visualized in addition to the medial and lateral gutters.35 As the blunt trocar is introduced through the triceps tendon and joint capsule, it is placed directly on the bone of the olecranon fossa. As the trocar is held in place, the cannula is advanced to the bone. The return of fluid with trocar removal confirms successful entry, and the arthroscope can then be introduced. This portal also provides an alternative site for insufflation of the joint with an 18-gauge spinal needle and sterile saline. Several common procedures can be performed through this portal site, including the removal of olecranon spurs and loose bodies and contouring or humeral fenestration of the olecranon fossa for ulnohumeral arthroplasty.35,36

Posterolateral Portal.

The location of the posterolateral portal is 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip and immediately lateral to the triceps tendon (see Fig. 2-6). Insertion of the trocar is directed toward the olecranon fossa, passing just lateral to the triceps tendon and through the posterolateral joint capsule. Visualization of the olecranon fossa and the medial and lateral gutters is afforded through this portal site.

The posterolateral portal can be used interchangeably with the straight posterior portal for viewing and instrumentation of the olecranon fossa and the medial and lateral gutters. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the ulnar nerve when instrumenting the medial gutter. The ulnar nerve is susceptible to injury posterior to the medial epicondyle, where it transverses obliquely and just superficial to the medial capsule of the elbow.33

Accessory Posterolateral Portal.

The posterolateral aspect of the elbow consists of the radiocapitellar joint and the lateral olecranon process. This portal is useful for the excision of a posterolateral plica, excision of lateral olecranon spurs, and débridement of the radial side of the ulnohumeral articulation.41 The placement of this portal can be accomplished in the area between the midlateral portal and the posterolateral portal, which is 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip. Spinal needle localization under direct visualization is suggested for accurate portal placement to address pertinent pathology. There is limited risk to neurovascular structures. However, the triceps tendon and ulnohumeral articulation are at risk for iatrogenic damage with errant trocar or instrument placement.27

Surgical Technique

After the administration of general anesthesia, the patient is transferred to the operative table and placed in the prone position, with attention to all pertinent prominences and to securing the airway. The shoulder is placed in 90 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation, with the elbow suspended in 90 degrees of flexion (see Fig. 2-2). A nonsterile upper arm tourniquet is applied. An arm board, parallel to the operating table and centered under the shoulder, is used to support a rolled towel bump and the operative extremity. A DuraPrep solution is used to prepare the arm and forearm. An impervious, sterile stockinette is applied to the hand and covered with self-adherent Coban to seal the hand and forearm contents from the operative field. Standard sterile draping is followed by exsanguination of the limb with an Esmarch bandage. The tourniquet is inflated.

All pertinent landmarks are outlined, with emphasis on locating the ulnar nerve, olecranon process, and medial and lateral epicondyles (see Fig. 2-3). The course of the ulnar nerve is palpated, and it is evaluated for subluxation. An 18-guage spinal needle is introduced into the straight posterior portal site, and the joint is insufflated with 20 to 30 mL of sterile saline until resistance is felt (see Fig. 2-3). Intra-articular injection can be confirmed with the observation of slight elbow extension as the joint fills.

The proximal anteromedial portal site is established 2 cm proximal to the epicondyle and immediately anterior to the intermuscular septum (see Fig. 2-4). A blunt trocar and cannula for a 4.5-mm arthroscope are introduced through a nick made in the skin with a no. 11 blade knife and advanced distally toward the radiocapitellar joint. The trocar is advanced while in contact with the anterior aspect of the humerus, which ensures protection of the anterior neurovascular structures by the brachialis muscle. An egress of fluid with trocar removal confirms intra-articular placement. The 30-degree, 4.5-mm arthroscope is introduced, and diagnostic arthroscopy of the anterior compartment ensues.

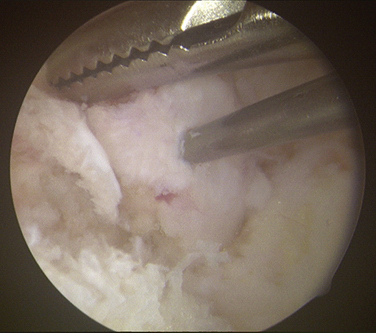

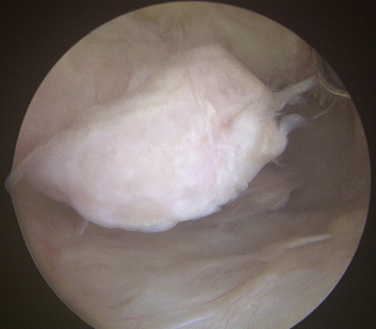

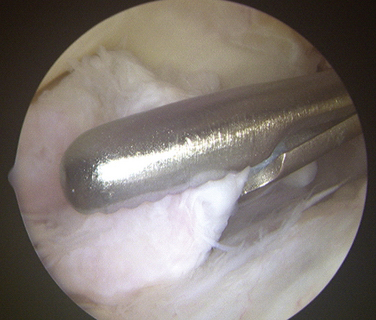

Loose bodies in the anterior compartment of the elbow are frequently found within the coronoid fossa (Fig. 2-7). Extraction of these osteochondral fragments is conducted after establishing a proximal anterolateral portal under direct spinal needle localization or by using and inside-out technique. The skin entry site for this portal is 2 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and 2 cm anteriorly. The spinal needle is removed, and a no. 11 blade knife is used to incise only the skin. A blunt trocar and cannula are inserted into the elbow while maintaining constant contact with the anterior humeral cortex as the trocar is advanced. This minimizes the risk of damaging the radial nerve on transversing the soft tissue. A meniscal grasper is introduced through the proximal anterolateral portal and used to remove any loose bodies (Fig. 2-8). If the size of the osteochondral fragment exceeds that of the cannula, it may necessitate piecemeal removal or the use of a motorized shaver. In certain cases, the grasper can be used to pull the cannula and fragment together through the soft tissue and out of the body. This can be accomplished by rotating the grasper as it is removed from the soft tissues while maintaining firm grasp on the fragment. Alternatively, a spinal needle may be needed to skewer and stabilize the loose body for retrieval with a grasper (Fig. 2-9).

FIGURE 2-7 A large, loose osteochondral loose body is visualized in the anterior compartment of the elbow.

FIGURE 2-8 A grasper is used for the removal of a large loose body from the anterior compartment of the elbow.

After thorough evaluation of the anterior compartment and loose body removal, attention is focused on the posterior compartment. The water inflow is generally switched to the proximal anteromedial cannula.26 The straight posterior portal is established using a no. 11 blade knife 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon (see Fig. 2-6). After introducing the 30-degree, 4.5-mm arthroscope into the straight posterior portal, the posterolateral portal is created 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip and just lateral to the triceps tendon under direct spinal needle localization (see Fig. 2-6). Commonly, a motorized shaver in the posterolateral portal is used to remove soft tissue obscuring the view to the olecranon fossa. The straight posterior portal and the posterolateral portal can be used interchangeably for removal of loose bodies. The olecranon fossa should be evaluated in its entirety because it is a common source of loose bodies.

The arthroscope is then introduced into the medial gutter from the straight posterior portal. A milking maneuver can be performed from a distal to proximal direction on the medial side of the elbow, which often propels loose bodies posteriorly.26 In the lateral aspect of the elbow, entry through an accessory posterolateral portal or midlateral portal is needed for débridement. These portals are localized under direct visualization with a spinal needle. A cannula, trocar, and motorized shaver are introduced in succession through the established portal. Often, a soft tissue plica or synovial band may need to be removed with the shaver for adequate visualization. In this posterolateral location, loose bodies are often hidden, and it is imperative that a thorough evaluation be performed.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

The primary goal in the postoperative period is to attain a full range of motion. Surgeons should refrain from splinting the elbow and instead encourage use of the operative extremity immediately postoperatively. Dressings should not interfere with early flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. Institution of a home exercise program or physical therapy should be emphasized. Patients should return to the office within 1 week to check the wound and monitor the range of motion. Aggressive physical therapy should begin immediately if improvements in motion are not attained.

CONCLUSIONS

It is well documented in the literature that the success rates for arthroscopic loose body excision from the elbow approach 90%.4,24,25 These findings have been supported by the work of O’Driscoll and colleagues, who reported 71 consecutive patients undergoing loose body removal.6 All patients with isolated loose bodies reported clinical improvement after arthroscopic removal. However, failure to address the primary pathology responsible for loose body production (i.e., osteoarthritis) results in limited patient improvement over time.6,14

1. Burman M. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: a cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:349.

2. McKenzie PJ. Supine position. In: Savoie FH, Field LD, editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:35-39.

3. Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:102-107.

4. O’Driscoll SW. Elbow arthroscopy for loose bodies. Orthopaedics. 1992;15:855-859.

5. O’Driscoll SW. Elbow arthroscopy: loose bodies. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000:510-514.

6. O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow: diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:84-94.

7. Savoie FH. Arthroscopic management of loose bodies of the elbow. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2001;9:241-244.

8. Savoie FH. Guidelines to becoming an expert elbow arthroscopist. J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2007;23:1237-1240.

9. Andrews JR, Baumgarten TE. Arthroscopic anatomy of the elbow. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:671.

10. Wiesler ER, Poehling GG, et al. Elbow arthroscopy: introduction, indications, complications, and results. In: McGinty JB, Burkhart SS, Jackson RW, eds. Operative Arthroscopy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 2003:661-664.

11. Byrd JW. Elbow arthroscopy for arthrofibrosis after type I radial head fractures. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:162-165.

12. Jones GS, Savoie FH. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277-283.

13. O’Driscoll SW. Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:691-706.

14. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Gordon R, MacKay M. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:437-443.

15. Baumgarten TE, Andrew JR, Satterwhite YE. The arthroscopic evaluation and treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:520-523.

16. Ruch DS, Cory JW, Poehling GG. The arthroscopic management of osteochondritis dissecans of the adolescent elbow. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:797-803.

17. Savoie FH, Field LD. Basics of elbow arthroscopy. Tech Orthop. 2000;15:138-146.

18. Menth-Chiari WA, Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Arthroscopic excision of the radial head: clinical outcome in 12 patients with post-traumatic arthritis after fracture of the radial head or rheumatoid arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:918-923.

19. Andrews JR, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97-107.

20. Clarke R. Symptomatic lateral synovial fringe of the elbow joint. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:112-116.

21. Smith JP 3rd, Savoie FH, Field LD. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:47-58.

22. Thomas MA, Fast A, Shapiro DL. Radial nerve damage as a complication of elbow arthroscopy. Clin Orthop. 1987;215:130-131.

23. Moskal JH, Savioe FH, Field LD. Elbow arthroscopy in trauma and reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:163-177.

24. Boe S. Arthroscopy of the elbow: diagnosis and extraction of loose bodies. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57:52-53.

25. McGinty J. Arthroscopic removal of loose bodies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13:313-328.

26. Savoie FH, Nunley PD, Field LD. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214-219.

27. Savoie FH, Field LD. Anatomy. In: Savoie FH, Field LD, editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:3-24.

28. Baker CL, Jones GL. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:251-264.

29. Poehling GG, Ekman EF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Inst Course Lect. 1995;44:217-228.

30. Rubin CJ. Prone or lateral decubitus position. In: Savoie FH, Field LD, editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:41-47.

31. O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. In: Morrey BF, editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:120-130.

32. Lindenfield TN. Medial approach in elbow arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:413-417.

33. Lynch GJ, Meyers JF, Whipple TL. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:191-197.

34. Poehling GG, Whipple TL, Sisco L. Elbow arthroscopy: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:222-224.

35. Lyons TR, Field LD, Savoie FH. Basics of elbow arthroscopy. In: Price CT, ed. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:239-246.

36. Plancher KD, Peterson RK, Breezenoff L. Diagnostic arthroscopy of the elbow: set-up, portals, and technique. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1998;6:2-10.

37. Stothers K, Day B, Reagan WR. Arthroscopy of the elbow: anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:449-457.

38. Field LD, Altchek DW, Warren RF. Arthroscopic anatomy of the lateral elbow: a comparison of three portals. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:602-607.

39. Aboud JA, Ricchetti ET, Tjoumakaris F, Ramsey ML. Elbow arthroscopy: basic setup and portal placement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:312-318.

40. Poehling GG, Ekman EF, Ruch DS. Elbow arthroscopy: Introduction and overview. In: McGinty JB, Caspari RB, et al, eds. Operative Arthroscopy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:821-828.

41. McClung GA, Field LD, Savoie, FH. Diagnostic arthroscopy and loose body removal. Surg Tech Sports Med. 2007;22:211-219.

42. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications in elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:25-34.

43. Papilion JD, Neff RS, Shall LM. Compression neuropathy of the radial nerve as a complication of elbow arthroscopy: a case report and review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:284-286.

44. Rodeo SA, Forester RA, Weiland AJ. Neurologic complications due to arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:917-926.

45. Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Anterior interosseous nerve injury following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:756-758.

46. Casscells SW. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks [editor’s comment]. Arthroscopy. 1987;2:190.