CHAPTER 4 Diagnostic colonoscopy

Key Points

1 Anatomy

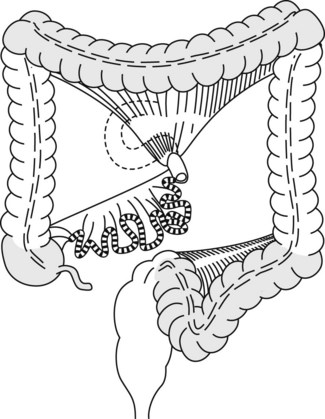

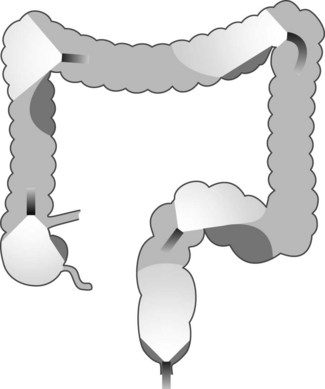

The colon comprises mobile segments (Fig. 1) (cecum, transverse colon, sigmoid colon) whose length depends on the size of the mesocolon, which attaches these segments to the posterior abdominal wall and the fixed segments (ascending colon, hepatic flexure, descending colon, rectum). The splenic flexure is partially attached by the phrenocolic ligament, the length and rigidity of which enable it to descend and become rounded on insertion of a colonoscope.

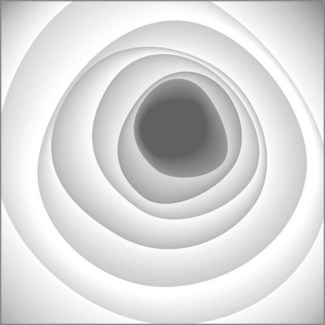

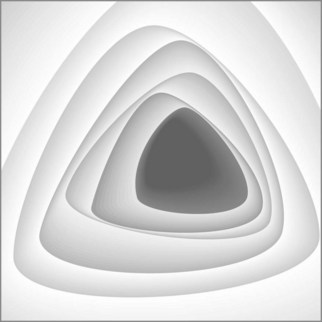

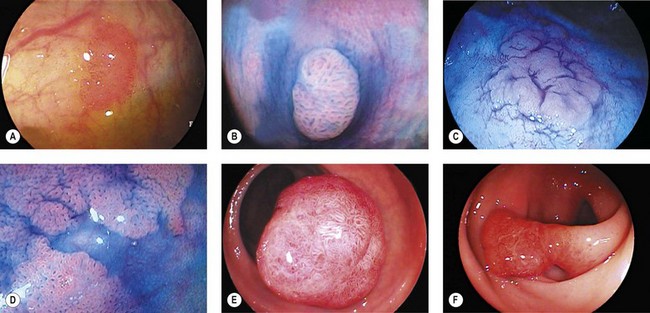

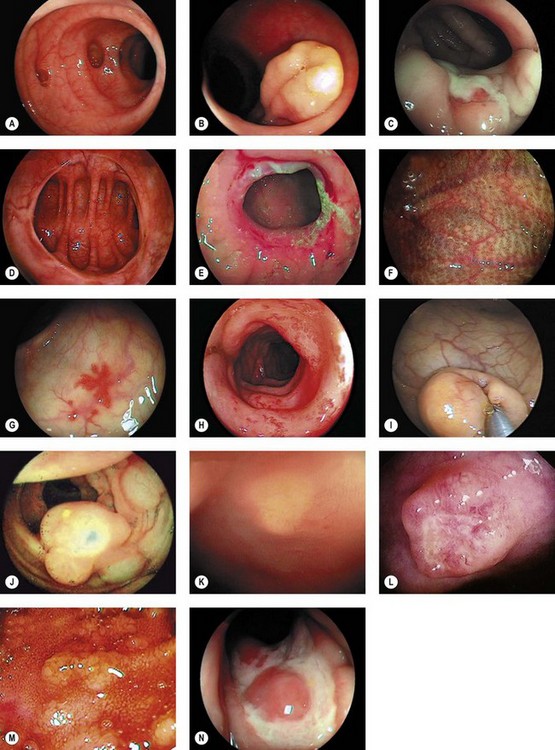

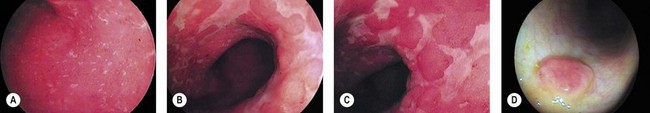

The rectum is 12–15 cm long beginning from the anal margin. It is the shape of an elongated ampulla and is segmented by three or four mucosal folds (valves of Houston). The sigmoid varies in length, depending on the length of its mesocolon. The colonic lumen and haustrations in the descending or sigmoid colon are generally circular (Fig. 2). The splenic flexure exhibits a blue area that is attributable to the impression of the spleen. The lumen of the transverse colon is triangular (Fig. 3).

2 Indications for colonoscopy (TC)

2.1 Patients at average risk of colorectal cancer (CRC)*

2.2 Surveillance of asymptomatic patients at high risk of CRC

2.3 Surveillance of asymptomatic patients at very high risk of CRC

Box 1 Amsterdam II criteria for HNPCC

2.4 Surveillance of patients after resection of one or more colonic polyps

5 Preparation of the examination room (Box 3)

Box 3 The minimum equipment required for a colonoscopy room

5.1 Setting up and testing endoscopes

5.2 Setting up and testing additional equipment

0.2% indigo carmine. It should be ready for use in a 50 mL syringe; colitis surveillance requires 150–200 mL, so it is useful to make it up in a bag of 0.9% saline

0.2% indigo carmine. It should be ready for use in a 50 mL syringe; colitis surveillance requires 150–200 mL, so it is useful to make it up in a bag of 0.9% saline Pure carbon black (‘Spot’, GI Supply Inc., Camp Hill, PA, USA) can be used to mark the site of a lesion before surgery, or for marking where a polyp was removed so that the area can easily be identified during subsequent screening colonoscopy. Sterile India ink suspension is an alternative but has been associated with immunological reactions

Pure carbon black (‘Spot’, GI Supply Inc., Camp Hill, PA, USA) can be used to mark the site of a lesion before surgery, or for marking where a polyp was removed so that the area can easily be identified during subsequent screening colonoscopy. Sterile India ink suspension is an alternative but has been associated with immunological reactions6 Handling the colonoscope

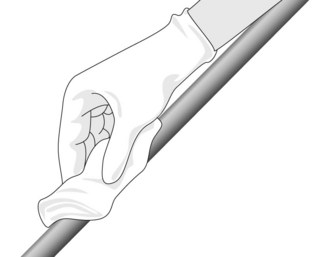

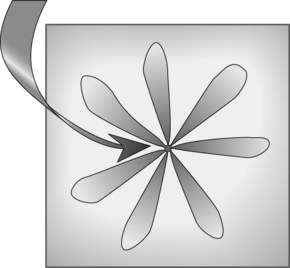

Colonoscopy is performed by a single endoscopist who holds the control handles in their left hand (insufflation, aspiration, washing with the index and middle fingers, lever for up/down angulation between the thumb and index finger). The right hand advances or withdraws the apparatus, and introduces instruments into the biopsy channel. As it advances, the lubricated colonoscope is held between the thumb and index finger (Fig. 4).

6.1 General principles

![]() Clinical Tips

Clinical Tips

Loop management

How do I know if I have a loop?

Suspect a loop if there is loss of one-to-one movement as you advance the colonoscope.

How do I reduce a loop?

The endoscope is torqued clockwise or in rare cases anticlockwise and then withdrawn.

6.2 Bowel preparation score

The Ottawa bowel preparation quality score is determined by scoring the right, mid and left colon as well as the score for the quantity of fluid within the entire colon and adding the four scores together (Table 1), the range being 0-14.

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Score right (R), mid (M) and left (L) colon separately (quality of preparation) | |

| No liquid | 0 |

| Minimal liquid, no suction required | 1 |

| Suction required to see mucosa | 2 |

| Wash and suction | 3 |

| Solid stool, not washable | 4 |

| Score the entire colon (overall quantity of fluid) | |

| Minimal | 0 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Large | 2 |

| Total score: R + M + L + Fluid = __ / 14 | |

7 Examination technique

7.1 Preparation of the colon

Various preparations are available including:

In general, there is little to choose among them in terms of efficacy and all require clear, careful explanation to patients beforehand and full compliance if good results are to be achieved. Serious reports of major complications, particularly with sodium phosphate preparations, have recently led to many countries issuing safety notices regarding the use of bowel preparation in general and NaP in particular (see Warning and Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of sodium phosphate (NaP) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) bowel preparation solutions

| NaP | PEG | |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | Low | High |

| Palatability | + | ± |

| Cost | Low | Low |

| Side-effects | Cramps; caution in patients with cardiac or renal failure; hypovolemia and electrolyte shifts | Bloating and vomiting secondary to large volume |

| Bowel cleansing | +++ | ++ |

7.2 Bowel preparation in specific situations

7.3 Taking PEG solution bowel preparation

7.3.2 Ingestion in two amounts (best suited to an examination performed in the morning)

Box 5 All patients should undertake the following

Stop taking any medications containing iron or charcoal 1 week before colonoscopy. Omit fiber supplements, e.g. ispaghula for at least 1 week

Example of colonic preparation with PEG for colonoscopy in the morning

3 days before the examination: fiber-free diet as documented above.

![]() Clinical Tips

Clinical Tips

Achieving good bowel preparation

7.4 Colonoscopy technique

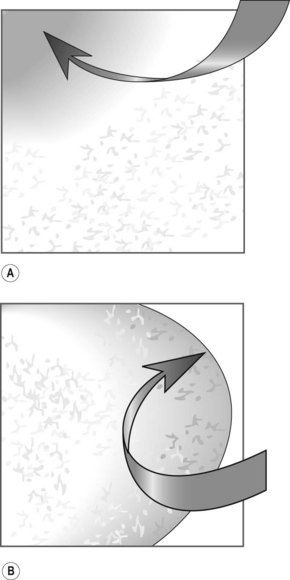

Examination of the rectum presents few problems. The presence of residue is normal. It is important to examine the low rectum in retroflexion (Fig. 8). This is performed by inserting the colonoscope to approximately 20 cm and then tipping up with the big wheel. The small wheel occasionally needs to be moved slightly to the right or left to fully visualize the low rectum. It is essential to be gentle and attempts should cease if there is resistance or pain.

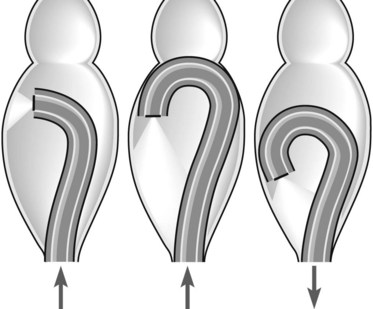

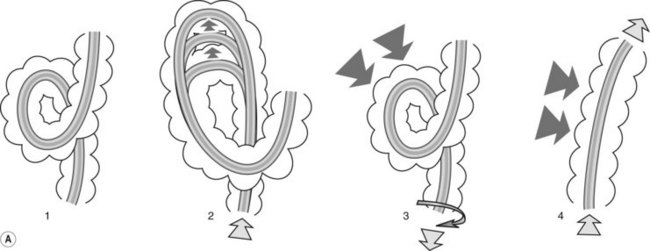

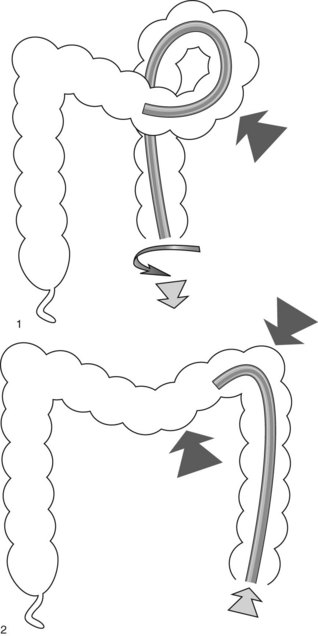

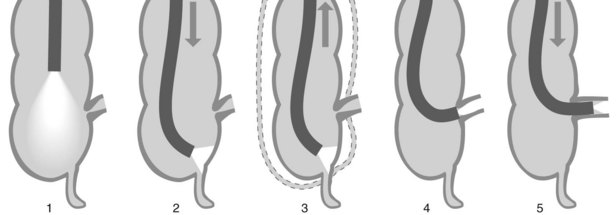

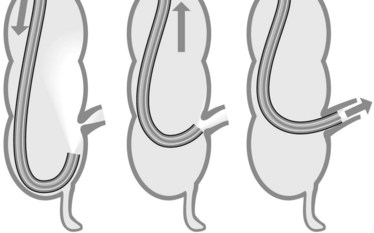

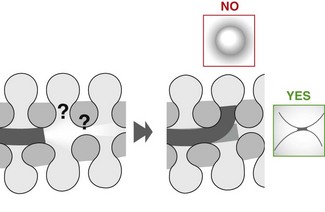

7.4.1 Alpha loop

Alpha loop (Fig. 9). The colonoscope passes along the concave part of the sacrum in the pelvis (rectum). In the abdomen (sigmoid colon), it passes upwards and forwards then turns downwards and backwards to enter the descending colon, resulting in the formation of a spiral anteroposterior loop. In this case, there are usually no problems passing through the sigmoid-descending colon junction.

7.4.2 Omega loop

Omega loop (Fig. 10). Sometimes the colonoscope creates an acute flexure in the sigmoid colon during insertion. The sigmoid-descending junction, between 40 and 70 cm from the anal margin, appears as an arc of mucosa against a duller background. It may be closed and give the impression of a pouch.

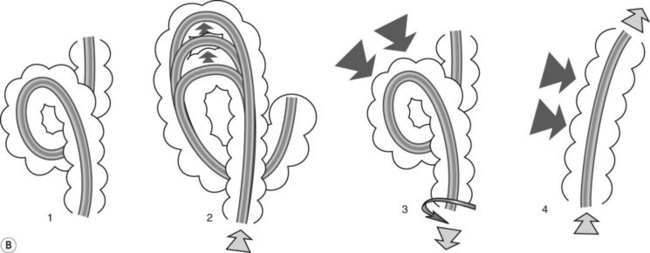

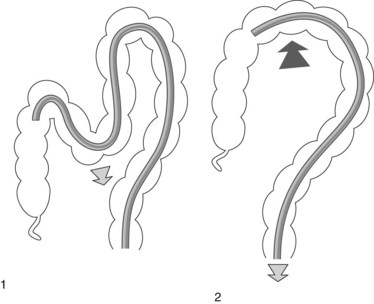

A reversed splenic flexure (Fig. 12) combined with a mobile descending colon is the commonest cause of unexplained problems advancing the colonoscope. If a loop of this type is suspected, reducing it by anticlockwise rotation should be considered. To prevent the loop reappearing, compress the splenic flexure and pass through it.

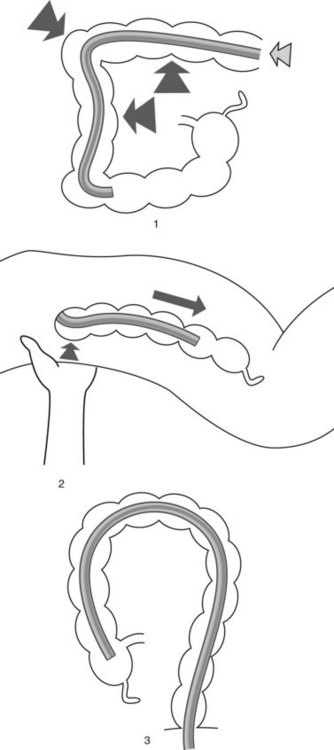

Passing through the transverse colon (Fig. 13) may be the cause of a new problem if there is a long mesocolon (formation of an omega or alpha loop as in the sigmoid, requiring the same maneuvers to reduce it). After passing the midline, it is then necessary to repeatedly straighten the transverse loop so as to concertina the colon onto the colonoscope. Aspiration, changing the patient’s position and abdominal compression (left iliac fossa to keep the sigmoid in position, left hypochondrium to lower the splenic flexure, umbilical palpation to keep the transverse colon in position) will help with this.

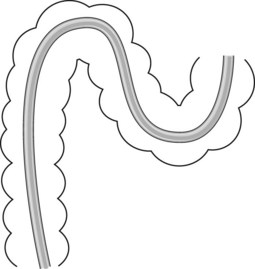

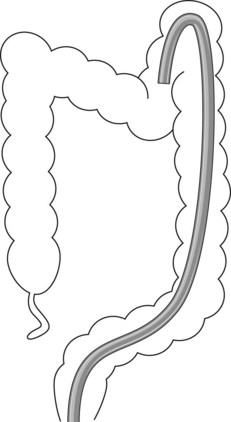

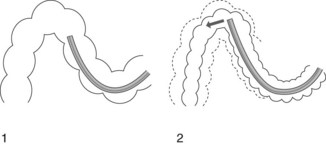

If there are problems passing through the hepatic flexure, it may be helpful to position the patient in left lateral decubitus to open the flexure. Once past the hepatic flexure (the optimum maneuver (Fig. 14) is a combination of aspiration, angulation, withdrawal of the endoscope and abdominal compression), descent into the ascending colon is usually straightforward. The colonoscope should then be advanced as far as the cecum (Fig. 15) with the aid of aspiration and compression of the transverse colon and/or sigmoid colon, lifting the right lumbar fossa or changing the patient’s position (right lateral decubitus).

7.5 Four maneuvers may be used to intubate the ileocecal valve

Place the colonoscope under the ileocecal valve (1, 2); usually with the patient supine the valve will be seen in the 7–9 o’clock position

Place the colonoscope under the ileocecal valve (1, 2); usually with the patient supine the valve will be seen in the 7–9 o’clock position7.6 There may be problems advancing the colonoscope

In such problematic cases, a magnetic imager system or using a pediatric colonoscope may be useful.

7.7 Locating the tip of the colonoscope

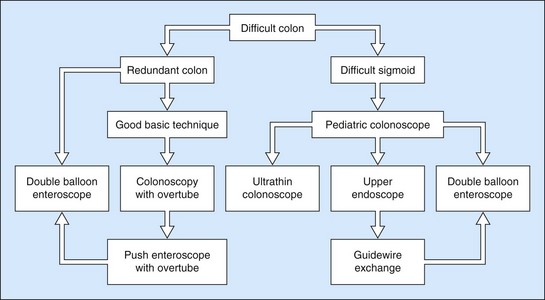

7.9 The approach to the patient with a very difficult colon

Patients with a very difficult colon are patients in whom other experienced colonoscopists have failed to reach the cecum. A flowchart for the approach to use in this group of patients is shown in Figure 19. We recommend using a magnetic imager (Scopeguide) in this group of patients if it is available.

Figure 19 Algorithm for the management of patients with a very difficult colon.

(With permission from Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:938-944.)

Narrowed or angulated sigmoid colon:

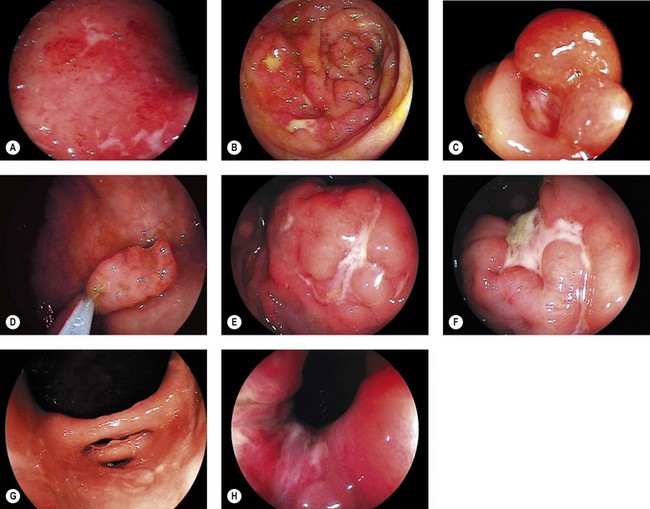

8 Colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease

8.1 Endoscopic appearance

A variety of lesions occur and often co-exist:

8.2 Endoscopic assessment of severity

9 Complications of colonoscopy

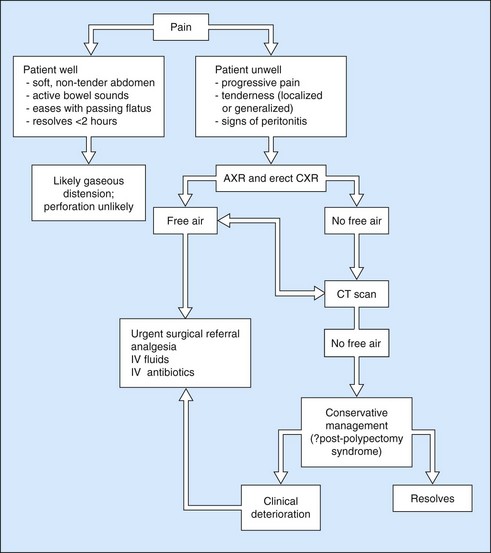

Mortality is rare, although the exact incidence is difficult to define. Figures of 0–0.02% and even 0.07% are quoted. Most deaths occur in frail, elderly patients with major co-morbidity and result from myocardial infarction, strokes or pneumonia. Approximately 5% of colonoscopic perforations are fatal. Complications are classified below (see also Table 3).

| Timing | Comments |

|---|---|

| Pre-colonoscopy | |

| Bowel preparation | Incontinence |

| Fluid and electrolyte shifts, dehydration | |

| Renal failure (NaP) | |

| More common in elderly with cardiac or renal disease | |

| During colonoscopy | |

| Sedation-related | See Chapter 2.3 |

| Instrumentation-related | Cardiovascular-arrhythmias, hypertension due to autonomic responses to stretching mesentery/viscus |

| Pain – excess air insufflation or loop formation | |

| Perforation: see text | |

| Incarceration in hernia sac | |

| Splenic hematoma/rupture | |

| Cecal/sigmoid volvulus | |

| Pneumatosis coli | |

| Intervention-related | Perforation: see text |

| Post-polypectomy syndrome | |

| Bleeding (acute or delayed) |

9.1 Perforation

The incidence of perforation is approximately 1 in 1000–2000 procedures but in some studies, is higher in patients undergoing biopsy or polypectomy. Other studies have found that perforation risk is related to polyp size (especially >2 cm) and location (right colon) rather than the overall number of polypectomies performed. Perforation can be pneumatic, mechanical or intervention-related. Pneumatic perforation is more likely in the cecum or when inflammation causes bowel wall-thinning, e.g. in severe colitis. Mechanical perforation results from forceful insertion of the colonoscope lacerating the wall. It is more likely when the bowel wall is weakened by inflammation, ischemia or diverticulosis. Interventional-related perforation results from thermal injury during polypectomy. Other factors contributing to perforation are listed in Box 7.

Several scenarios are possible:

![]() Clinical Tips

Clinical Tips

9.1.1 Post-polypectomy syndrome

Patients who have undergone polypectomy may develop ‘post-polypectomy syndrome’ in which a transmural thermal burn leads to pain, tenderness and fever but no free air is seen on radiology: most cases settle conservatively. The approach to a patient complaining of pain after colonoscopy is shown in Figure 21 and steps to minimize the chances of perforation are outlined in the Clinical Tips box above.

9.4 Hemorrhage

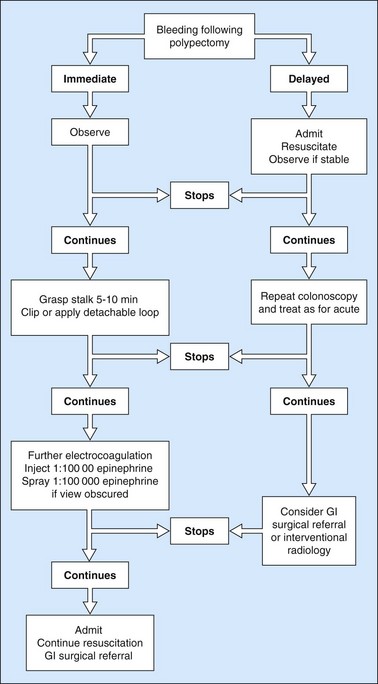

Bleeding after polypectomy (Fig. 22) is more common with polyps >2 cm, thick-stalked polyps and after EMR or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Mechanical transaction of the stalk (‘cheese-wiring’) before effective thermal effect occurs is a significant contributory factor. Bleeding may be immediately apparent but can be ‘secondary’, occurring up to 14 days later. Most bleeding is minor and stops spontaneously but severe bleeding requires intervention (Box 8).

9.6 Incomplete removal of neoplasia

![]() Clinical Tips

Clinical Tips

9.7 Quality assurance in colonoscopy

Units and endoscopists should regularly audit their colonoscopy practice and assess the following:

10 Colonoscopy in children

Colonoscopy in children has several special features.

10.6 Indications

These are summarized in Box 10.

Box 10 Indications for colonoscopy in children

11 Images

Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, et al. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2533-2541.

Barthet M, Gay G, Sautereau D, et al. Endoscopic surveillance of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2005;37(6):597-599.

Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: adverse event reports for oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(1):15-28.

Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(4):373-384.

Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. (on behalf of the British Society of Gastroenterology and the Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland). Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups. Gut. 2010;59:666-690.

Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, et al. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2008;40(4):284-290.

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: Joint guidelines from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595.

Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):880-886.

Napoleon B, Ponchon T, Lefebvre RR, et al. French Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SFED) Guidelines on performing a colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38(11):1152-1155.

Qureshi WA, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: modifications in endoscopic practice for the elderly. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(4):566-569.

Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28.

Rex DK. Achieving cecal intubation in the very difficult colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:938-944.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627-637.

Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638-658.