24. Diagnosis – the purpose and process

Chapter contents

Introduction to the diagnosis chapters182

The purpose of making a diagnosis182

The process of making a diagnosis183

The stages of making a diagnosis184

The stages of taking a case history185

Pulling it all together188

Rapport188

Introduction to the diagnosis chapters

‘To see’, ‘to hear’, ‘to ask’ and ‘to feel/smell’ are the four traditional methods of diagnosis used in Chinese medicine. To use these diagnostic tools, practitioners both employ their senses as well as ask questions. Some styles of diagnosis pay more attention to one or the other of these methods. For example, contemporary Chinese herbalists emphasise asking questions about the complaint and the patient’s general condition. Although they also use hearing, looking and feeling, these are generally considered less important than questioning. In contrast, practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture ask fewer questions and are more reliant on seeing, hearing, smelling and feeling. For this reason the five chapters on diagnosis pay special attention to how practitioners can use and develop their senses in order to make an accurate Five Element diagnosis.

In this first chapter on diagnosis two main aspects are described. The first is how to record the case history and make a diagnosis, and the second is the importance of developing rapport and how to achieve it.

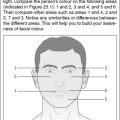

The second chapter (Chapter 25) covers the essential methods used when diagnosing the CF. These are the observation of colour, odour, sound and emotion.

The following chapter (Chapter 26) is about body language and observing a patient’s posture, gestures and facial expression. It illustrates how much assessment of a patient is carried out by simple observation.

The next chapter (Chapter 27) on diagnosis covers two important areas. One is reading ‘golden keys’. Golden keys are unusual aspects of a patient’s behaviour or values that may support a CF diagnosis. The other is determining the appropriate level of treatment the patient requires. This may be the body, mind and/or the spirit.

Finally, the fifth chapter of the diagnosis section (Chapter 28) covers much of what comes under the area of ‘to feel’ and the physical examination of the patient. The specific areas covered are pulse diagnosis, the Akabane test, feeling the three jiao and the palpation of the abdomen. These methods of diagnosis can indicate that an Element is significantly out of balance and they can also support the diagnosis of the CF. However, they are less important in actually determining the CF.

The purpose of making a diagnosis

The main goals of making a Five Element Constitutional diagnosis are:

• to diagnose the patient’s CF

• to determine if any other Elements require treatment

• to establish whether the patient has any blocks to treatment

• to ascertain the level of treatment required – body, mind or spirit

Diagnosing the patient’s CF

The main goal of diagnosis is to find the patient’s CF. Once the CF has been confirmed, it will be the basis of much of the treatment. This is because using points associated with the Organs of the CF are likely to have the most significant effect on the patient’s overall health. Having said this, there are situations when this is not the case. For example, acute problems such as infections usually respond better to points chosen to clear the symptoms directly. Also, patients with acute traumatic injuries have better changes from points that move qi in the area of the trauma than from treatment centred on the CF.

Diagnosing the other Elements

Determining the patient’s CF involves an assessment of all of the Elements. Whilst making the diagnosis the practitioner forms an opinion about the balance of each one. The basis for diagnosing an imbalance in any Element is the same as determining the CF. The main difference is the intensity and number of the diagnostic indicators. Knowing that an Element other than the CF Element is weak is crucial.

A person may be a Water CF, for example, but in the aftermath of an unhappy love affair the Fire Element may be devastated for a considerable period of time. Alternatively this person’s Metal Element could be shattered by a recent bereavement.

In many cases treatment on the CF greatly improves the balance of all of the other Elements. Sometimes, however, one Element does not respond and treatment also needs to be directed to that Element. In these situations the practitioner may decide to treat the affected Element as well as influencing it indirectly by treating the CF. This will re-establish harmony within the Five Elements, which will in turn help the person to overcome heartbreak or endure loss with greater internal strength and fortitude.

Diagnosing possible blocks

Next the practitioner needs to establish whether the patient has any blocks to treatment. If blocks are present, they have to be cleared first. They are:

• Aggressive Energy

• Possession

• Husband–Wife imbalance

• Exit–Entry blocks

Diagnosing the level of treatment

During the course of the diagnosis the practitioner assesses whether treatment should be directed more towards the patient’s body, mind or spirit. Determining which level most requires treatment is important as it affects point selection. More is written about this area of diagnosis in Chapter 27.

The process of making a diagnosis

Recording the main complaint, systems and other information

A Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist always takes a full case history. This involves asking about many areas including:

• the patient’s main complaint

• the health of the ‘systems’, such as the digestion, cardiovascular, urinary and reproductive system

• the general health of the patient’s parents and family

• the patient’s medical history and educational, work and personal history

• the patient’s current living and relationship situation, work, interests, etc.

A Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist does not use the actual content of this information in order to make a diagnosis of the CF, but it is still important in three ways.

• Firstly, many opportunities for emotion testing will arise whilst collecting this information. Emotion testing will be described in the next chapter. The practitioner can also notice the patient’s colour, voice tone and odour during this time. Rapport is also established.

• Secondly, it helps to set a benchmark for the patient’s current health. Patients are often most concerned about their main complaint when they first come for treatment. Consequently they may not mention other systems that are not functioning well. For example, some patient’s bowels may be too frequent or their sleep patterns less than optimum. Patients may also tell the practitioner about other areas of their lives where they are experiencing difficulties, for example in work situations, friendships or close relationships. When practitioners know about all of these areas they can monitor the patient’s progress. Many aspects of a patient’s health improve when the root is treated. Monitoring this information often tells a practitioner that the patient is getting better even when the main complaint has not yet responded. As well as helping to monitor treatment, patients will also benefit from a wider notion of what constitutes health.

• Thirdly, this information can, in spite of what was said previously, help to confirm the diagnosis. For example, the history of the complaint may reveal that it began shortly after leaving home, the break-up of a relationship or after a frightening experience. The emotional response to these situations may reveal which Element has become imbalanced. This information is never the basis of a diagnosis, but it can confirm and support it. People’s health and welfare depends on them being able to receive nourishment from all of the Elements on a regular basis. External changes to their ability to receive this nourishment may reflect on their health. The patient who developed multiple sclerosis after her child ran away or the patient who became ill after his one constant source of love and affection walked out, can be telling us something significant. Patients’ non-verbal expressions can be as significant as their words.

What a diagnosis does not involve

A Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist makes a diagnosis based upon the person who has the illness rather than the nature of the illness itself. Therefore the main complaint or symptoms suffered by the patient are important, but are not used to make the diagnosis. The fact that the patient is constipated, paralysed or suffering from migraines is not a basis for the CF diagnosis. The patient’s Western diagnosis, for example, rheumatoid arthritis, manic depression or diabetes, is also never the basis of a diagnosis. Symptoms often reveal that an Organ is dysfunctional but do not indicate whether that Organ is the primary or secondary cause of the problem.

The stages of making a diagnosis

The context of treatment

Throughout this book, when we refer to practitioners making a diagnosis, we assume they are working in a professional context. This means that the practitioner diagnoses, then treats a patient, and that this is carried out in the practitioner’s acupuncture practice.

Most practitioners sometimes find themselves making a diagnosis in other contexts. For example, a friend may call to consult on the telephone or someone at a party might talk about a problem she or he is having. It is useful for practitioners to apply their diagnostic skills in many different situations if they wish to develop them. It is not appropriate, however, to treat in these situations. We recommend that, if a diagnosis is to lead to treatment, the practitioner should carry out a complete diagnosis and have appropriate conditions under which to administer the treatment.

The two levels of activity during a diagnosis

While taking a case history, practitioners are frequently operating on two levels at once. Whilst doing the ‘business’ of taking the case history, they may also be making significant interventions and observations. Although there are various stages to the process of making a diagnosis, many of them can be done at almost any time. For example, looking at colour, smelling an odour, observing the person’s emotional state, recording childhood diseases or taking pulses can be done in any sequence.

Often more than one activity is carried out at any one time. For example, while practitioners are discussing and recording the patient’s main complaint, they may also be attempting to discern the facial colour, odour and sound in the voice. Alternatively, when a patient is describing a pain, as well as recording its nature, location and intensity, it may also be a perfect moment for the practitioner to give sympathy and assess the emotion of the Earth Element. There are more examples of ways that practitioners operate on two levels in the next chapter.

The stages of taking a case history

The following are the main stages of taking a case history. This is only one sequence and case histories can be taken in many different ways. Newly qualified practitioners or those just starting to use this system of acupuncture are recommended to more or less follow the sequence laid out below. At the same time, as long as the practitioner gains the essential outcomes of a Five Element Constitutional diagnosis (see above), then they can work in any order.

The stages of the case history are:

1 establishing rapport

2 taking the main complaint

3 questioning the systems

4 finding out about personal health history, family health history, relationships and present situation

5 ‘to feel’

6 ‘to see’

Establishing rapport

Establishing rapport is the first priority when making a diagnosis. Without rapport practitioners are operating without the patient’s trust. As a result patients are less likely to co-operate and disclose themselves freely. Instead they will wonder if they have chosen the right practitioner and will hold themselves back until they are sure. Although rapport-making is an activity that can be carried out on its own, it is also something that is done at the same time as taking the case history.

At various times when taking the case history, especially early on, the practitioner will focus almost exclusively on the development of rapport. At other moments it will be a background consideration. Although in one sense rapport comes first, it also continues throughout the case history. Rapport-making is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Taking the main complaint

Earlier it was stated that a traditional diagnosis is made up of four aspects. These are ‘to see’, ‘to hear’, ‘to ask’ and ‘to feel’. Taking the main complaint is mostly associated with the aspect of the diagnosis associated with ‘to hear’. Most patients come to treatment with one or more complaints and they expect the practitioner to listen to them carefully.

Early on in the interview, the practitioner may ask the patient ‘What would you like acupuncture to help you with?’ or ‘What is your problem, how long have you had it and what have you had done about it?’ The patient can then talk about the complaint in depth. Once the patient has described the problem, the practitioner asks further questions in order to gain a complete picture of the patient’s problem. It is essential for the practitioner to record the complaint in detail and in the patient’s own words. The patient may have more than one complaint and each should be dealt with in a similar way. The purpose of recording the complaint is to:

• help make a diagnosis of the patient’s CF as well as the state of the other Organs

• form an accurate assessment of the complaint in order to monitor progress

• discover and explore what happened around the time the complaint began

• create and maintain rapport by meeting the patient’s expectations and providing opportunities for compassion to be communicated

Patients do not necessarily remember how they were at the start of treatment. Keeping the information gained at the start can be useful later on so that patient and practitioner can evaluate the impact of treatment.

A well-recorded complaint will:

• be recorded in the patient’s own words

• record when it started and what was happening around that time

• describe where it is located

• describe its quality and the intensity, for instance, of the pain or sensations involved

• describe whether it is continuous or intermittent and, if intermittent, its frequency

• say what makes it worse or better

• record what the person can or cannot do as a result of the problem

• include any associated symptoms

• record what other treatments the patient has tried and any medication she or he has taken

Questioning the systems, or the ‘Ten Questions’

This stage covers what Western physiology describes as a patient’s ‘systems’. In Chinese medicine, questions about these areas are known as the ‘Ten Questions’. This section of the diagnosis is especially concerned with the ‘to ask’ aspect of the traditional diagnosis. Each area of questioning may involve a great amount of detail.

• Sleep. Quality – depth of sleep; how the patient feels in the morning on waking; restlessness or agitation at night. Quantity – time the patient goes to bed; when goes off to sleep; when wakes up. Insomnia – waking in the night; trouble getting off to sleep; waking early, reason for waking. Drugs – sleeping tablets. Dreams – dream disturbed sleep; recurring or frequent dreams; nightmares.

• Appetite, food and taste. Appetite – good, bad, ‘too good’; hungry but can’t eat. Digestion – good, bloating/distending when eats, indigestion, nausea, vomiting. Likes/dislikes – hot, cold, any taste preference or craving. Taste – bitter, sweet, salty, etc. Diet – when patient eats and what they eat on a normal day. How healthy is the patient’s ‘relationship’ with food?

• Thirst and drink. Quantity of fluid per day. Thirst – how thirsty. Type of fluid – hot/cold, tea, coffee, etc. Alcohol – how much, when, what, any history of drink problems.

• Bowels. When – are they regular, every day. Consistency – diarrhoea: how often, smell, colour, undigested food, watery; constipation: how often, dry, soft. Mucus, blood. Pain – strong/weak, when better/worse.

• Urine. Quantity – amount, frequency. Colour – light, dark, cloudy, blood. Odour – strong smell, no smell. Pain/distension – when better/worse. Enuresis.

• Sweating and temperature preference. Sweating – how much, e.g. normal, heavy, light; when, e.g. on exertion, day, night. Temperature – hot or cold; which area, for example, all over, deep inside or extremities.

• Women’s health. (i) Menstruation: regularity, length of period. Blood – colour, quality, quantity, clots, flow. Pain – type, time, frequency. Emotional changes. Age when started period. (ii) Discharges – colour, smell, amount. (iii) Pregnancy and childbirth: how many, any problems, e.g. miscarriages, infertility, type of birth, post birth. (iv) Menopause (if appropriate): what age; any problems, for example, flushes, emotional changes, lack of energy, etc. (v) Contraception (if appropriate) – pill, coil, etc.

• Head and body. Headaches – onset, time of day, location, type of pain, better/worse. Dizziness – onset, acute/chronic, strong/slight, better/worse, accompanying symptoms.

• Eyes and ears. Eyes: vision – normal/short/long sight; blurred vision; irritations, for example, red or blood-shot eyes; dryness; floaters; pain. Ears: quality of hearing; tinnitus – onset, character of noise. Numbness – where, when comes on.

• Thorax and abdomen. How are the chest; flanks; epigastrium; hypochondrium; abdomen – any pain or distension.

• Pain. Where; when comes on; full/empty (Maciocia, 2005, pp. 323-324); fixed/moving; better/worse with activity; heat or cold.

• Climate and season. Feel better/worse in any climate or season, e.g. cold, heat, damp, wind, dryness, etc.

There are other questions that the practitioner can also ask. These can include questions about a patient’s allergies, resistance to infections and changes in well-being and vitality at different times of day.

The main categories listed above are best described as ‘areas to question’, as each of them can involve many specific questions. The practitioner may wish to first ask an open question about each system such as ‘How are your bowels?’ or ‘How is your sleep?’ Once this has been answered, the practitioner may then ask the patient other more specific questions about that area.

For example, if the first question is ‘How is your sleep?’, then depending upon the answer, subsequent questions could be: ‘What time do you go to bed?’, ‘What time do you get up?’, ‘Do you wake in the night?’, ‘How many times?’, ‘How is your temperature when you wake?’, ‘Do you feel rested in the morning?’ and so on. The relevance of some of these questions is a basis for judging the patient’s progress and, depending upon the other Chinese medicine patterns the practitioner uses, the answers may also have diagnostic relevance.

The list of questions above is useful as a checklist and it enables practitioners to decide whether they have questioned all aspects of the patient’s health. Experience and sensitivity tell the practitioner when to go further and ask more questions and when to leave a topic. For example, after questioning menstruation many times, the practitioner is better able to evaluate whether the patient has a significant problem in the area or not.

For the Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist this information is used to determine in which respects a person’s body, mind and spirit is not working well. People often have a symptom or symptoms, which they think are unimportant so they do not include them with their main or subsidiary complaint(s). For example, a patient may be complaining of migraines and period pains, but they may also have night sweats and digestive problems. As these may well respond to the CF treatment, it is important that they are acknowledged and can be used to monitor progress. The migraines may be irregular, making progress difficult to assess. The improved digestion and the absence of night sweats may, however, confirm that treatment is being at least partially successful.

Personal health history, family health history, relationships and present situation

The information collected here concerns four broad areas: the patient’s health history; the family health history; relationships; and the patient’s present situation.

Questioning a patient’s personal history is often the most diagnostically important part of the taking of the case history. Patients may exhibit no obvious emotions when they recount their health problems and history. While discussing family and intimate relationships or difficult phases in their lives, however, they often reveal more of their emotions.

Rapport is crucial. Superficial rapport limits the patient’s willingness to disclose painful emotional areas. Patients give different answers to the same question depending on the trust they feel in the person asking the question. Excellent rapport allows the patient to reveal in which Elements the most intensely felt emotions are to be found.

Personal health history

It is important to see the patient’s current health problems in the context of their past health. The current complaint may be just one more instance of the same thing occurring over time or it may be the first time they have ever been seriously ill. The following are some guidelines topics to ask about:

• birth – premature, health at birth, wanted or otherwise

• early childhood rashes, digestion, illnesses (mumps, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, whooping cough, etc.)

• other past illnesses

• accidents, injuries or visits to hospital

• medication – it is obviously important to ascertain which medications are being taken. Some symptoms may be the effect or side-effect of a drug

• recreational drugs, including alcohol

• smoking

• difficult periods in the patient’s life

• schooling

• career

Family health history

Some families have hereditary diseases and other are known for being ‘long livers’. This information can explain the occurrence of some illness and it can also create false expectations on the part of some family members. The practitioner needs to find out about:

• health of parents

• family diseases

• siblings and their health

Relationships

As friendship and close relationships are an essential part of our welfare, an understanding of these is useful. The pattern of relationships, for example, the ability to maintain or not maintain them, can give supportive evidence for a CF. Discussion of these kinds of topics also often reveals emotions that were not evident while discussing the patient’s physical health. The practitioner should aim to cover the following areas:

• relationship with parents and siblings and other significant relatives

• friends at primary and secondary school

• significant friends

• significant teachers, mentors or authority figures

• marriages and sexual relationships

• children

Present situation

This term covers the patient’s present living situation:

• married or living with partner

• housing

• jobs, friendships, children

• religious or spiritual beliefs

• hobbies and interests

• hopes for the future

‘To feel’

The traditional notion of ‘to feel’ covers several things:

• pulse diagnosis (see Chapter 28)

• three jiao (see Chapter 28)

• palpating front mu points and back shu points (see Chapter 28)

• abdominal diagnosis (see Chapter 28)

• palpation of (and visually inspecting) the channels

• palpation of musculo-skeletal symptom areas for swelling, pain, temperature

• joint flexibility and range of motion

• skin temperature, moisture, texture

• nail strength

‘To see’

The ‘to see’ part of the diagnosis goes on throughout the case history, for example, when asking questions or during palpation of the abdomen. It includes such things as the following:

• the colour on the face

• the spirit as reflected in the sparkle of the eyes

• scars

• observation of emotional responses

Pulling it all together

Having collected the above information, the practitioner needs to sift through it and bring it together. Both inexperienced and experienced practitioners can end up with some degree of uncertainty. For example, a practitioner may be able to make a strong case for Wood but also a strong case for Metal. During the process of pulling the case history together, it is useful for practitioners to keep a list of any information they did not collect and any signs that they have doubts about. For instance, they may be unsure of the facial colour and wonder if it was yellow or green. They can then go back and concentrate on this aspect at a later treatment.

A beginner takes considerable time over this phase – sifting the information, separating primary from supportive evidence and trying to determine whether or not the symptoms, pulses or touch of the person are genuinely supportive of the CF diagnosis or simply insignificant. New practitioners may take more time pulling the information together than they took collecting it. More experienced practitioners start to pull information together as it gets collected.

So far we have concentrated on the content and sequence of collecting information. We turn now to rapport.

Rapport

What is rapport?

Rapport occurs when the patient feels close to the practitioner. It is not something that is either on or off, but is a question of degree. Rapport allows the patient to trust the practitioner. The level of trust achieved may not extend to other areas of the patient’s life, but is specific to the matters relevant in the practitioner/patient context.

Practitioners are concerned about rapport because it facilitates the following:

• It helps the practitioner to ‘emotion-test’ more effectively – good rapport encourages a patient to reveal more of their emotional self to the practitioner.

• It helps the practitioner elicit more accurate information and better understanding – the deeper the rapport, the more the patient can open up and reveal their inner world.

• It enables the practitioner to carry out treatments that affect deeper aspects of a person – without rapport the patient’s spirit is not accessible to the practitioner.

How does a practitioner make rapport?

Rapport often comes easily. There are, however, times when it doesn’t occur naturally and the practitioner needs to know how to generate it. In some cases rapport can also be improved. There is a big difference between ‘getting along OK’ and achieving a deep level of trust. Deep trust allows patients to feel sufficiently safe to reveal the intensity of their emotional world.

A mechanism for gaining rapport

People tend to trust those they have something in common with or who they perceive are like them. In Britain, for example, two people in a railway carriage, wearing the same football team’s scarf already have a bridge between them. In the USA, supporting the same baseball team can be a natural link. A person might meet someone who has a similar taste in music. They love the music and think, ‘A man who loves that music as much as I do can’t be all bad.’ Opposites may attract, but ‘similars’ gain rapport. A method for gaining rapport, therefore, is to create and draw attention to similarities.

In what respects can people become more similar?

In Box 24.1 is a list of areas for which similarity helps to generate closeness. Take, for example, the tempo at which a person operates. Tempo will manifest in the rate of a person’s speech, gestures and body movements. Someone who is slow will speak slowly, gesture slowly and move slowly. Someone who is fast will speak quickly, gesture quickly and move quickly. Tempo is a fundamental characteristic of a person. A fast person has difficulty feeling comfortable with a slow one, and vice versa. Fast practitioners with slow patients will create more rapport as they slow down. Slow practitioners with fast patients will create more rapport as they quicken their tempo.

Box 24.1

| Body posture | Gestures (especially repetitive key gestures) |

|---|---|

| Tempo (voice/body/mind) | Voice tone and volume |

| Values | Breathing |

| Use of language and metaphors | Words and phrases |

To improve rapport, the practitioner can match each of the aspects in Box 24.1. (For further reading, see Brooks (1989) and Richardson (2000). These are detailed and enthusiastic. See also O’Connor and Seymour (2003) and Young (2004), both of which have sections on rapport.)

How does a practitioner learn to do this?

The best way to learn how to match is to take one area at a time and to match it. For example, when learning to match someone else’s tempo, practitioners can devote time (in daily life or in specially arranged sessions) to adjusting their tempo so that it is similar to other people’s. People have a range of tempos, but if overall the practitioner is faster than the patient, he or she needs to slow the tempo down a notch – to close the gap. To do this, the practitioner thinks, gestures, breathes and speaks more slowly.

Sometimes it is easy to match but sometimes it is not. For example, speaking more slowly, to some degree, is easy. However, a slightly greater shift can tip the balance and learners may say that they no longer feel like themselves. People have said they feel ‘odd’, ‘not myself’ and even ‘weird’ when moving outside their normal comfort zone. It is important that practitioners remain comfortable whilst matching and realise that they are in control and can decide the degree to which they match. In order to gain rapport with another person it is not necessary for the practitioner to be exactly the same. It is much more important to make similar movements or gestures. A small shift towards similarity can create a large amount of rapport.

It is often useful to learn to match in a class with a teacher or observer present. In this situation, unlike real life, the person learning can make mistakes and be given feedback from a peer acting as a ‘patient’. People’s perception of how much change they have created is not always easy to determine and an outside observer can also be helpful.

Learning to match another person is also best done in small stages. For example, practitioners may learn to adjust the tempo of their speech until they can do it without thinking. They may then learn to match the variation in the pitch of the voice until they can also do this without thinking. Practitioners’ skill in matching soon increases and they can rapidly gain the ability to match without thinking. Sometimes saying the word ‘match’ to themselves can act as a trigger so that they automatically start to match the patient.

Which areas are essential to match?

With reference to Box 24.1, the following areas are the most important ones to match to gain rapport:

• body posture

• gestures generally

• voice tone and volume

• tempo (voice/body/mind)

The following can make a big increase in the capacity to gain rapport:

• the most repetitive or ‘key’ gestures

• values

The remaining areas to match can be important, but are difficult to learn:

• breathing

• words and phrases

• the use of language and metaphors

Matching and diagnosis

As well as enabling practitioners to gain rapport, matching can also increase their ability to make a diagnosis. When practitioners are matching a patient’s tempo, voice tone, posture and key gestures, they are not just observing passively. In order to carry out the matching the practitioner is both observing and at the same time taking on these other aspects of the patient. The act of matching automatically makes the practitioner feel more like the patient. The more matching is carried out, the more this increases. Thus the practitioner’s understanding of the patient increases too. Hence, matching is in part a diagnostic method.

The practitioner might also ask if there a danger of becoming too like the patient. When practitioners have learned to match and do it consciously, it is relatively easy to stop. They have clear control over ‘getting the feel of the patient’ and returning back to be themselves. However, if practitioners naturally match and do it unconsciously, then they need to be careful. Some practitioners complain that they feel ‘drained’ by patients or even take on their patients’ symptoms. This can be an extreme form of unconscious matching. If this is done momentarily, it can be useful for diagnosis. Otherwise, it is dangerous and practitioners risk becoming ill. Learning to match consciously helps a practitioner to gain better control over this unconscious and harmful matching.

How much rapport do we need?

Developing trust

It can be tempting for practitioners to believe that they only need to ask the right questions and the patient will answer correctly. However, gaining deep rapport involves far more than the practitioner just turning up, being pleasant and asking the right questions. It involves inner development and the engagement of the practitioner’s full compassion.

Matching is an excellent way for the practitioner to be in harmony with the patient. It also encourages the patient to develop trust and confidence in the practitioner. For many patients to reveal their emotional world to the practitioner a very deep level of rapport is required. Some patients easily show their anger, fear, need for sympathy or sadness to their practitioner. Others do not. These patients need to feel a great deal of trust in the practitioner and this places more demands on her or him.

Acceptance and compassion

Above all it is necessary for practitioners to give patients their full attention. The practitioner needs to see the patient’s internal pain and suffering. As well as matching, acceptance and compassion are essential requirements. These are not possible unless the practitioner is prepared to be touched and affected by the patient’s story and feelings. Patients can find it especially difficult to reveal grief and sadness unless the practitioner is able to resonate with and respect those feelings.

Being fully present

When making rapport practitioners also need to use their intention (yi). Guo Yu described a situation when his intention was not ‘fully there’ and how it hindered his ability to bring about a cure (see Chapter 6, this volume, for more on the inner development of the practitioner and the situation Guo Yu was describing). If the practitioner’s intention is not fully present, then the patient’s spirit will not be wholly available for the treatment. If rapport is limited, the practitioner’s ability to diagnose may be affected as the practitioner is unable to observe aspects of the patient’s spirit. In consequence treatments will be less effective.

Developing deep rapport improves the quality of information collected, makes emotion testing more effective and enables the patient to become more open and ready to change when the practitioner carries out the treatment. There is no exact answer to the question ‘How much rapport do you need?’ Practitioners who have virtuosity (linghuo) have developed their rapport-making skills and these are an enormous benefit to them in their practice.

Summary

1 ‘To see’, ‘to hear’, ‘to ask’ and ‘to feel/smell’ are the four traditional methods of diagnosis used in Chinese medicine.

2 The main goals of making a Five Element Constitutional diagnosis are:

• to diagnose the patient’s CF

• to determine if any other Elements require treatment

• to establish whether the patient has any blocks to treatment

• to ascertain the level of treatment required – body, mind or spirit

3 Making a diagnosis involves both using the senses to discern colour, sound, emotion and odour and also listening to the content of what the patient is saying.

4 A Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist always takes a full case history. This involves asking about many areas including:

• the patient’s main complaint

• the health of the ‘systems’, such as the digestion, cardiovascular, urinary and reproductive system

• the general health of the patient’s parents and family

• the patient’s medical history and educational, work and personal history

• the patient’s current living and relationship situation, work, interests, etc.

5 Rapport is vital to a Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist as good rapport facilitates a deeper level of diagnosis and treatment.