25. Diagnosis – the key methods

Chapter contents

Introduction192

Colour192

Odour194

Sound196

Emotion199

The stages of emotion testing202

The testing process for each Element207

Introduction

This chapter covers the key methods of diagnosis used in Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. These are:

• colour

• odour

• sound

• emotion

Colour

The background

The colours associated with each Element are:

• Wood – green

• Fire – red/lack of red

• Earth – yellow

• Metal – white

• Water – blue

There are four significant places for a Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist to observe colour. These are by the side of the eye, under the eye, in the laugh lines and around the mouth. Some people’s colour shows in broad swathes on the sides of the face. The colour at the side of the eye is the most important area to notice when diagnosing the CF.

Sometimes at least two colours appear on the face. For example, there may be a green colour around the mouth and a different colour next to the eye. In this case the colour by the eye normally takes precedence. 1

One anomaly about facial colour is that Fire CFs, rather than showing a red colour, normally have a dull pale facial colour, especially at the sides of the eyes. This colour is called ‘lack of red’.

The difference between seeing and labelling

There are two distinct steps for the practitioner to take when learning to observe colour. Firstly, practitioners need to see the colour. Secondly, they need to be able to label it. Seeing is not the same as labelling.

Seeing colour

Some practitioners try to label colour before they have seen it properly. In this case they have left out the first step. They need to learn to see colour first. This can be an important part of the training when learning Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. More is written about this below.

Labelling colour

Other practitioners see a distinct colour but then do not know what to call it. Some people have a wider range of labels for colour than others. For example, a person who mixes colour for a paint manufacturer or a person who paints landscapes is likely to have more labels for different colours than solicitors or linguists who use their visual acuity less. It can be helpful if practitioners take the time to observe a wide range of colours, especially those seen in nature, in order to increase their colour ‘vocabulary’. Being able to label colour is essential as it links what practitioners observe with their Five Element diagnosis.

Seeing facial colour

In order to increase their ability to see colours, practitioners can set themselves certain tasks. For example, one task may be to spend 15 minutes sitting at the window of a café or restaurant observing the facial colour of those passing by. Another option may be to observe the colour of 10 different people during the course of a day. It may also be useful for practitioners to observe colour with a fellow learner and compare what they see. In order to fine-tune their skills, practitioners need to look at the facial colour of almost everyone they meet.

When observing colour, it is important that practitioners relax their eyes. Squinting, moving the head forward or getting anxious make it less likely that the practitioner will be able to discern the colour. Below we discuss how practitioners can develop their sensory acuity by:

• comparing colour

• observing in different lights

• being aware of how light is reflected

• softening their eyes

Comparing colour

Comparing colour increases sensory acuity. For example, looking at two faces simultaneously (or at least quickly moving back and forth) heightens practitioners’ visual awareness. Acupuncturists who are working on their own, looking at only one patient, can easily cross the habituation threshold. To focus their minds on the sensory input it can be useful for them to compare different areas of the patient’s face. This gives them several colours to observe. To help them to do this they can ask themselves a question, such as, ‘How do the colours on either side of the face compare?’ or ‘Which colour is paler?’ The landscape painter does this naturally as his or her eye travels back and forth from field to canvas and back again.

In a group, when people are learning to see colour, it can be useful to line up two to five people to compare their different colours.

Observing in different lights

Natural light is important when observing colour, so practitioners may sometimes need to ask patients to step outside or over to the window of the treatment room in order to find the best light. It is often useful to ask patients to face the light and to then turn their heads slowly from one side to the other. This will enable the practitioner to observe the facial colour on all areas of the face.

Observing in different lights can be useful as this helps the practitioner to understand the benefits of good light. Mid-winter in Britain is not a good time for natural light. The skies are greyer and the days are shorter. Many treatment rooms have little natural light and artificial light subtly distorts the true colour. Making comparisons between artificial and natural light, one side of the room and another, bright sunlight and soft northern exposure, enables a practitioner to get used to the effects of different lights. A change in colour will easily convince the practitioner that bringing the patient to the best source of light is a good idea.

Awareness of how facial colour can be distorted

Light is reflected off walls, blankets and clothes. A patient with a green shirt or pink blanket may appear different when wearing a brown shirt or using a blue blanket. It is useful for the practitioner to experiment and notice any differences caused by different lights.

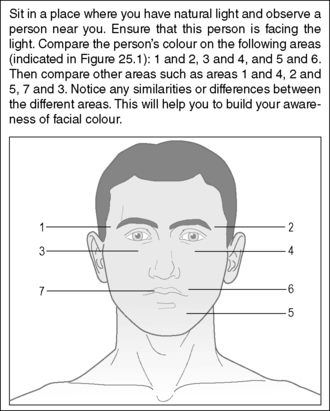

It can also be useful to remember that make-up distorts colours and the practitioner may need to ask some patients not to wear make-up on the day of treatment. Figure 25.1 describes an exercise to help develop the practitioner’s awareness of facial colour.

|

| Figure 25.1 • |

Softening the eyes

Hard eyes limit the range of our vision and make it difficult to see colour. The more we relax and soften the eyes the wider our vision and the better we can see the patient’s colour (Box 25.1).

Box 25.1

The following is an exercise to soften the eyes:

Two practitioners, A and B, work together and sit opposite each other.

A closes her or his eyes and then relaxes them as far as possible.

He or she then concentrates on the eye itself and just behind it.

When the eye feels somewhat different, A opens the eyes just for a second or two and looks at B’s colour.

A then closes her or his eyes and repeats the softening.

A then once more opens the eyes, this time for slightly longer and repeats until she or he experiences seeing the colour better and at the same time seeing ‘more’.

Labelling colour

Sometimes labelling is easy. The colour is obviously blue or obviously green. On occasions, however, there is a dispute as to whether that colour, which two people are both looking at, is yellow or green, or is it both or a mixture of the two? When there is disagreement, it is best to revert to observing the colour again and looking at it in the best light conditions possible. Confusion decreases over time, but some uncertainty may remain.

When practitioners are unsure of the correct label, the following method can help them to learn to identify colour. If, for instance, a practitioner can’t decide whether the patient’s colour is yellow or green, she or he can still make a diagnosis based on other factors such as the emotion, odour or voice tone. If that diagnosis is then confirmed by a positive response to treatment, then the practitioner might make an inference about the colour, based on the confirmed diagnosis. For example, if the treatment response confirms that the patient is a Wood CF, then in spite of the earlier confusion between yellow and green, the practitioner might conclude that the predominant colour was green. Learning in this way is probably the easiest way for practitioners to improve their ability to recognise colours. (The ability to recognise odour and voice tone can also be partly learnt in this way.)

Once the practitioner becomes aware that reflected colour can change the patient’s colour, it is inevitable on many occasions to ask the patient to stand in front of a window where the light is optimum. The practitioner can then ask the patient to turn their head slowly from side to side which presents the best conditions for viewing colour. It seems that shyness stops practitioners from doing this, but getting the colour right is far more important. This is also the best position in which to examine the tongue.

Odour

The background

The odours for each of the Elements are:

• Wood – rancid

• Fire – scorched

• Earth – fragrant

• Metal – rotten

• Water – putrid

As soon as there is an imbalance in a person’s qi, their odour will change. During the diagnosis the practitioner will endeavour to smell the patient’s predominant odour.

Smelling and labelling odours

Smelling odours

As with colour, smelling more keenly is an essential stage to go through before learning to apply the correct odour labels. After taking a case history, a common complaint from practitioners is that they didn’t smell an odour. The reason for this is simple. Most people do not need to be able to smell to get through their day. Apart from smelling smoke (indicating a fire), a gas leak or perhaps food to determine whether it has gone off, most people do not regularly use their ability to smell. Compared to a cat or dog, both of which will constantly be checking their environment for odour information, humans barely use their sense of smell. Thus to use odour regularly with patients requires some development.

Labelling odours

When practitioners learn to hone their sense of smell, they still have the problem of identifying the smells correctly. The labels for the odours listed above are not particularly helpful, as many people do not have clear ideas about, for example, the smell of rotten as opposed to the smell of rancid.

Increasing the ability to smell

One problem when smelling odour as opposed to looking at colour is that a colour is more constant and objective. If practitioners look at the colour by the eye, then look away again, they expect to look back and see the same colour again. This is especially true if they do it quickly and they or the patient do not change position or alter the light. This is less true with odour because people habituate to smells very quickly. This habituation is similar to what happens if we repeat a word endlessly and it seems to lose its usual meaning. We may initially smell something strongly, but then the smell quickly fades. The fragile nature of an odour is a matter of degree, but it is less constant and substantial than colour. Box 25.2 describes an exercise to help develop the ability to smell odours.

Box 25.2

The following is a short exercise to carry out while reading this book. Smell in sequence the front of your hand, the back of your hand, the sleeve of your shirt and then your shoe. Can you tell differences? Without trying to use the labels associated with each Element, can you give a name to the smells? If you were presented with them in random order, could you say which was which?

When to smell the odour

Because people habituate quickly, it becomes important to ‘catch’ odours by surprise. One of the best times for practitioners to smell a patient’s odour is when they have just entered the treatment room. If a patient has removed some clothing, the odour seems to fill a room and build up, especially if the patient has been in the room for several minutes. The practitioner can smell the hallway and then smell the room, in a matter of one to two seconds. In this way they can use contrast and comparison to accentuate the odour. After the practitioner has been in the room for more than a minute or two, the chances of detecting the odour become considerably less.

If a patient is lying under a blanket in a warm room this may also provide the practitioner with an opportunity to smell the odour. When the blanket is lifted in order to check the temperature of the three jiao or to carry out abdominal diagnosis a smell may be detected.

It can also be useful for practitioners to notice the odour in the area between a patient’s shoulder blades. The odour is often more distinct here as this is a difficult area for people to clean.

How to smell the odour

The more the practitioner is relaxed the easier it is to smell the odour. ‘Trying hard’ to smell is especially ineffective. Sometimes the odour becomes stronger and clearer when it is least expected. When a practitioner is deeply relaxed, for example, when taking pulses, the odour may suddenly become more apparent.

It is important for practitioners not to obviously sniff or show that they looking for an odour or rapport can easily be lost. The patient may wrongly conclude that the practitioner thinks she or he has an offensive smell!

Artificial smells

Another point the practitioner needs to remember is that patients are often wearing a number of artificial and acquired smells that cover up the underlying odour. These range from perfumes, hairsprays, what the patient last ate, deodorants, toothpaste, whatever is clinging to clothes (freshly dry cleaned or not) to flatulence. It is often appropriate for the practitioner to ask patients not to wear perfumes and other artificial smells on the day they come for treatment.

The labels of the smells

Most practitioners’ ‘smell vocabulary’ is less developed than their colour vocabulary. The vocabulary they do have often includes many judgmental words like ‘awful’, ‘yucky’ or ‘gorgeous’. These do not help a person to improve their ability to label odours. In Table 25.1 an attempt is made to describe the various odours.

| Element | Conventional label | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | Rancid | Like rancid butter or cut grass. Slightly prickly inside the nose and a bit musty at the same time |

| Fire | Scorched | Like clothes coming out of the tumble dryer or the smell of ironing or like burnt toast |

| Earth | Fragrant | Unlike ‘fragrant’ flowers. Heavy, cloying and sweet. A smell that hangs around the nostrils |

| Metal | Rotten | Like rotting meat or a rubbish bin or garbage truck where many different substances are decomposing. Grabs the inside of the nose with tiny prickles |

| Water | Putrid | Like a mixture of a urinal and chloride of lime. Can also be like stale wine, a tom cat’s spray or bleach. A sharp smell |

As with colour, one way practitioners can enhance their ability to recognise odours is to make a diagnosis using the other three key methods of diagnosis and then link the odour to that Element. Some practitioners are naturally gifted in the ability to smell odours, but for many it is their least developed sense. The challenge for them is to develop their ability to use it effectively. Box 25.3 suggests a practical way to improve the ability to distinguish smells.

Box 25.3

‘Smell-bottles’ are a useful device when learning to smell odours. Their purpose is to enable practitioners to:

• Increase the amount they consciously smell

• Refine their ability to make smell distinctions

• Increase their ability to remember smells

• Assist them in labelling smells

Smell bottles are not high-tech. All that is needed is to:

• Acquire five small, identical, opaque, containers that have tight-fitting tops to keep any material and its odour inside. These may be bought specially, but many foods and medicines come in these kinds of containers.

• Mark distinct numbers on the bottom, for example from one to five, and place something that is natural and has a distinct odour in each one.

• Open each bottle one at a time and get used to the smell. At this stage look at the number on the bottom.

• Mix the bottles up and open them one by one. Smell the contents and try to put them in the order of one to five.

This game enhances the practitioner’s ability to smell, discriminate, remember and possibly label the smells in order to remember them. There are many variations to the game above. For example, the practitioner can start with just two bottles and work up to five, or, to make the exercise more difficult, the contents of the bottles can be made more similar. This game can also be played with a partner.

Sound

The background and principles

The voice tones associated with each Element are:

• Wood – shouting/lack of shout

• Fire – laughing/lack of laugh

• Earth – singing

• Metal – weeping

• Water – groaning

A normal voice tone contains each of the five sounds when they are appropriate. When an Element is out of balance, one sound predominates or becomes absent. When there is reasonable balance these voice tones are appropriate to the emotion being expressed. When there is imbalance they are inappropriate. The Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist listens to the voice tone in order to determine which sound is most out of balance.

When learning to listen to voice tones, practitioners first need to be able to distinguish between a congruent or incongruent voice tone and emotion. They can then evaluate the voice tone in conjunction with the emotion the patient is expressing and the content of the discussion.

Voice tone and emotion

When people are relatively whole and balanced, their channels of emotional expression are also relatively balanced. For example, a shouting tone denotes anger or an attempt to assert oneself. To hear this sound when someone is actually angry is appropriate. To hear the same sound when a person is expressing love or warmth is inappropriate. Box 25.4 describes an experiment to help practitioners distinguish between congruent and incongruent sounds.

Box 25.4

To understand the difference between congruent and incongruent sounds and emotions, try this experiment. Feel friendly and say ‘hello’ in an angry tone. Feel sympathetic and express this in a frightened tone of voice. Try using other incongruent voice tones and emotions. Notice how often you hear these inconsistencies as you go about your daily activities. Often, without training, practitioners just accept these blatant incongruencies as ‘just how someone is’. They are, however, important diagnostically.

Once people are alert to inconsistencies between the voice tone and emotion they often notice them more and find that they sound strange. What is even stranger, however, is that people often hear incongruency in everyday life and do not register it as unusual.

Throughout the treatment practitioners need to maintain a heightened state of awareness and alertness as to whether the patient’s voice tone is appropriate or not. Paying attention to the nuances in the voice makes demands on the practitioner, but diagnosis by voice tone is often a key part of the diagnosis of the CF. Time spent honing the ability ‘to hear’ is time well spent. The focused awareness required can also intensify the rapport between patient and practitioner.

Descriptions of the sounds

When learning to recognise an imbalance in patients’ voice tones, the first stage is to recognise the difference between each sound. In order to clarify these differences, a more detailed description of each voice tone is listed below.

Fire is ‘laughing’

The ‘laughing’ sound is not an actual laugh, but is more like a pre-laugh. It is as if a person is being given a little tickle and might break into real laughter. The sound itself tends to move upward in the body.

Some people have a voice tone that is lacking in laughter. This voice tone has no sparkle or animation to it. It can easily be mistaken for a groaning voice. A distinguishing feature is that it often has a croaky quality, as though it comes from deep in the person’s throat or chest.

Earth is ‘singing’

The ‘singing’ voice is used by a mother when she is soothing her upset child. It can also be compared to the voice of a rider calming an agitated horse. It is the voice tone often used by someone being ingratiating. The sing, as compared with other voices, has more frequent and more extreme variations in pitch.

Metal is ‘weeping’

The weeping voice is not actually weeping, but more as if the person is about to weep. It often tails off in volume near the end of sentences, as if the lungs are too weak to sustain their power for a whole sentence. It is often a bit thin, quavers or sounds fragile. To use a photographic analogy, the density of the weeping voice often has a lower resolution and fewer pixels. The underlying grief can create a ‘catch’ or slight choke in the voice.

Water is ‘groaning’

A groaning voice lacks the variations in pitch of a singing voice and is often recognised for being flat or expressionless. It is as if a normal voice has a flat upper and lower governor that squashes any upward and downward variation in pitch. It is easy to imagine its connection with fear. If a person is in a dangerous situation, say, in a room where there is reported to be a poisonous snake, then in order not to create panic or frighten the snake, she or he might easily put a clamp on variations in pitch, keeping the voice level and constant. The voice can often ‘drag’ towards the end of the sentence.

Wood is ‘shouting’

‘Shouting’ usually implies an increase in loudness and, while often true, loudness is not the essential quality of this voice tone. Another way of describing this sound is that it contains an ‘emphasis’. Emphasis means that one syllable, for example, of a three-syllable word, is louder. For instance, if a person says the word ‘exactly’ and emphasises the middle syllable – exactly. Another description of this sound is that it is clipped, implying an abruptness or sharpness. Such a voice can be quiet but assertive.

Some people have a voice tone that lacks any strength to it. This voice is unnaturally quiet or becomes so when the person is challenged or uncertain. It does not have the power or force that would be expected from that particular person. The practitioner often needs to strain slightly to catch what is being said. It is as though the voice cannot be projected sufficiently to easily travel across the intervening distance between the two people.

Box 25.5 suggests an exercise to develop the ability to discriminate sounds.

Box 25.5

This is a useful way to learn the different voice tones:

1. Ask two members of a group to carry on a conversation.

2. Take the components of sounds – emphasis, variation in pitch or lack of it, the direction of movement of the voice in the body and the density of the voice – and listen to the two people speaking.

3. One by one, ask, ‘Which of the two people has more emphasis in the voice?’ ‘Which of the two has more variation in pitch?’ and so on.

This exercise uses comparison to assist sensory discrimination. It also encourages the listener to pay attention solely to the sound. The latter can be difficult. Practitioners get attracted to the content of people’s conversation and are afraid they will miss something important while listening to the voice tone. It can be helpful to close one’s eyes, but perseverance may also be necessary. Once it becomes second nature to hear the voice tones, then the listener also loses the fear of not absorbing the content of what the person is saying.

The content and emotional context

The next stage is the comparison of the voice tone with content of the person’s speech and their emotional expression. A person may be speaking about the family coming to stay for Christmas and may also be smiling. At the same time, the voice tone may contain more than an appropriate amount of emphasis. She or he is talking in a friendly way, but the voice tone is angry.

Another person may speak about having physical or emotional pain with a laugh in the voice. Another person speaks about an enjoyable time with the family and looks happy, but the voice is groaning. Another person is saying they are angry about an incident when they were ignored, but their voice is singing.

In all of these cases, the practitioner of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture will be observing the imbalance or incongruency – the lack of resonance between the content of the mind, the verbal and non-verbal expressions and the sound in the voice. It is less easy to hear an imbalance in the voice tone when a person is comfortable and chatting. The practitioner is much more likely to notice incongruous sounds in the voice when the patient is talking about something that carries emotional charge.

Training to recognise the least appropriate sound

There are three important stages to recognising the inappropriate voice tone.

The first stage to remember is that the practitioner is aiming to identify the Element that is most out of balance. If the sound that resonates with Wood is the least appropriate voice tone, then this is evidence for the Wood Element being the CF.

The second stage is to learn to identify the sounds normally associated with anger, joy, sympathy, grief and fear and to be able to sort them out from other sounds and characteristics of the voice. When learning Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture people start with different talents. Some can only make some rough distinctions at first while others immediately have a much more conscious appreciation of the different voice tones and can imitate and recognise them with ease. It is useful for beginners to practise, perhaps using the exercises suggested above.

The third stage is to monitor three things simultaneously:

• the contents of the person’s mind, for example, are they thinking about or talking about something that would make most people angry?

• the non-verbal expression of the emotion, such as the person’s posture, gestures and facial expression

• the sound in the voice

While monitoring these three areas, the practitioner needs to pick out which sound is most out of balance. This may sound easy, but it is a bit like patting the head, drawing circles on the stomach and making circles with the elbows, all at the same time. It requires practice to do each part separately before they can be successfully combined.

Emotion

Background

The emotions associated with each Element are:

• Wood – anger

• Fire – joy

• Earth – sympathy

• Metal – grief

• Water – fear

When people are in good health the five emotions are expressed appropriately. For example, people laugh at a joke or shout when they are angry. When their qi is imbalanced they feel and show emotions inappropriately. For example, they may show joy even when discussing something painful, or experience no fear in a situation that is dangerous. People may have a lack of or an excess of an emotion when their qi is imbalanced and some patients may swing between the two, especially if it is the emotion connected to their CF.

The practitioner assesses which emotions are being expressed inappropriately. These are sometimes assessed simply by observation and sometimes by interacting with the patient and observing the patient’s response. It is often difficult to draw a distinct line and say that a certain response is definitely inappropriate. For example, how long is it appropriate to be devastated by the death of one’s child?

Sometimes it is easy to diagnose an emotional imbalance. A person may exhibit a particular emotion that jars and which makes the practitioner think, ‘that is strange!’ Sometimes it is the intensity of an emotion that is striking. It may be understandable that somebody is angry with the person that made her or him redundant, but surely not that cross, not that bitter.

Sometimes what is striking about a particular patient is that whatever situation arises and whichever emotions could be regarded as appropriate, one emotion always seems to predominate. The practitioner understands, for example, that a patient might be cross with her parents for various events that have happened. The patient might also be angry with her first boyfriend for leaving her and with her husband for how he is with the children, etc., etc. What is most noticeable is that whatever event occurs, anger is the predominant emotional response.

The importance of the emotion

Of the four key diagnostic criteria used by Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturists, emotion is the most complex and any judgements about normality or appropriateness can have important moral and cultural implications. At the same time the inappropriate emotion provides one of the most accurate keys to a patient’s CF. By observing a patient’s least fluent emotion, practitioners can also increase their understanding of how this same emotional pattern appears in many other aspects of a patient’s life.

Emotional language

What is meant by an emotion?

The English language distinguishes at least three descriptions of different types of emotions. These are an ‘incident’, a ‘mood’ and the ‘feeling capacity of a temperament’.

An incident creates a one-off emotion. For example, a person becomes very angry when insulted.

In contrast, a mood goes on for some time. For example, a patient may say they have been depressed on and off for several weeks. The statement about mood does not mean that the person has been having the emotion continuously. It suggests that the feeling comes and goes or surfaces from the background and becomes more foreground.

In further contrast, a temperament may predispose someone to incidents of emotion that are typical of that temperament. For example a person may describe her or himself by saying ‘I am a fairly happy person. I generally feel happy and always have been’ or ‘I tend to be an anxious person. I get frightened over the smallest things.’ A temperament is like a mood but one that is more entrenched in the person’s character.

The Element–emotion association is one of temperament. A person who has a particular CF is prone to experiencing certain emotions because the qi of that Element is constitutionally weaker. When the qi of an Element is healthy this permits the emotions associated with that Element to be expressed in a balanced way. When the qi of an Element is out of balance it means that the emotions resonating with that Element become less resourceful.

Because the CF is constitutional, people’s personalities, at least in part, develop around the imbalanced emotion. A Fire CF, for example, will have less resourceful emotions around joy, a Water CF around fear, and so on. Thus assessing emotions is really observing the qi of an Element.

Assessing a patient’s emotions

The patient’s most inappropriate emotion can be assessed in two ways. Sometimes it is possible for the practitioner to observe it by just watching the patient. At other times it is less obvious and the practitioner must ‘test’ the patient’s emotion.

Observing emotions

When people’s most inappropriate emotion is on the surface it can easily be observed. For example, when people seem frightened about almost everything, they may be judged to have excessive fear that might, therefore, be used to support a diagnosis of Water.

Emotional expression is conveyed by observing different aspects of a person, for example, eyes, facial expression generally, the words a person uses, the tone of voice, the body posture and specific gestures. Sometimes the label for a person’s emotion may be obvious. At other times, it is less clear and different observers may disagree about what they observe. (See Ekman, 2007, Chapter 1, for the scientific case that the emotional expression of the face exists across cultures.)

The difference between observing and testing emotions

Often patients will exhibit some of their emotions to the practitioner and there is no need to deliberately ‘test’ them. When practitioners just observe, however, they may not get information about all of the Elements. People are often happy to reveal some emotions, but not others. Also, a patient who is shy and withdrawn may avoid being expressive. The practitioner may have no idea that a particular emotion is so inappropriate or intense unless she or he evokes it. Emotion testing attempts to overcome these problems.

Emotion testing

In contrast to observing a patient, a practitioner may ‘test’ a patient’s emotional response. ‘Emotion testing’ involves the practitioner consciously attempting to evoke emotions in the patient (see Box 25.6). The practitioner then observes the response. Does the patient respond at all? Does she or he respond more intensely than seems appropriate to the context? Does the voice, facial expression or body language change, and does this change indicate disharmony in the patient’s qi? The practitioner assesses whether the emotions resonant with each Element are in balance or out of balance. 2

Box 25.6

The patient’s mind being like a theatre stage is a metaphor that can be used to explain the process of testing an emotion. The practitioner is a theatre director whose job it is to create the right dramatic moment – using props, other actors, etc. – on the stage of the patient’s mind. ‘The right moment’ means the moment that would naturally produce the emotion the practitioner is attempting to induce. For instance, a patient mentions a loss of a pet. The practitioner asks what the patient especially liked about the pet. In order to answer, the patient remembers moments of pleasure with the pet. The stage is now set to gently remind the person of the loss and to invite a feeling of grief. The practitioner’s non-verbal expression of grief – through facial expression, body posture and tone of voice – is a key part of the ‘props’ on the stage of the patient’s mind. How the patient responds will be an outward show of the flow of the qi of the Metal Element.

At the crucial moment of testing the emotion, practitioners must be able to access the emotion inside themselves. No patient will respond to sympathy, joy, grief or any of the emotions if the practitioner is not authentic in its expression. Saying sympathetic words to someone will not touch them if it does not come from the heart. This is why practitioners must be able to access each of the emotions in themselves and why this is one of the most important goals in the inner development of the practitioner of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture.

The limitations of the practitioner in the skill of emotion testing form one of the greatest obstacles to becoming an excellent diagnostician. It is the cause of many mistaken diagnoses. The practitioner tries to induce an emotion in a patient but because the feeling was not truly present, the patient does not respond as they would if the feeling had been authentic. In the example of testing grief given in Box 25.6, the patient will respond totally differently to two different practitioners. An acupuncturist who has good rapport and genuinely accesses grief about the death of the pet, will receive a different response from another practitioner who really thought grieving about a pet a bit pathetic. The ability to test grief, and all the other emotions, effectively depends upon such differences.

Emotion testing during the practitioner– patient interaction

Emotion testing is like talking with a friend and from the outside it should be indistinguishable. The patient will be unaware that the practitioner is doing anything other than taking a case history and making rapport. An emotion test that is overt or is obvious to an observer has not been skilfully carried out.

Conversing with a friend does not require a high level of concentration. Emotion testing, however, does require focused awareness and while carrying out a test practitioners also need to:

• monitor what is happening – one part of the practitioner’s attention is acting as an observer and is monitoring what information has been collected so far and what to do next

• pay attention to the more subtle non-verbal changes in the patient

• use all of their knowledge of the Element and people in general to make an assessment of the appropriateness of the emotional response

The use of the expression ‘emotion testing’

The phrase ‘emotion testing’ is not an ideal one, particularly because the word ‘test’ is used in conjunction with emotions. It does, however, accurately describe what practitioners do. The ‘test’ evokes an emotional response resonant with an Element. The emotion is a movement of qi and this gives the practitioner a chance to observe the movement of qi resonant with a particular Element. There is no better way of prompting an Element to reveal its nature to the practitioner.

Emotions and culture

It is important for practitioners to be aware of the range of emotional responses of people from different cultures. (See Kaptchuk, 2000, footnote 16 on pp. 168–169, for a discussion about how people in one culture speak differently about their emotions from those in another culture.) It is much easier to have a sense of the appropriateness of emotional response if the patient is from a similar culture to the practitioner. It would be very hard, for example, for a practitioner born and brought up in the Midwest of the USA to have a great understanding of the emotional responses of an Australian Aborigine. Even among people from the same country there can be significant differences in emotional expression dependent upon age, gender, ethnic background, social class, subculture, etc. For example, grieving processes vary in different cultures. Different cultures tolerate very different levels of aggression amongst members. Men tend to accept sympathy from male practitioners less readily than from female practitioners. The practitioner must have a broad vision of these factors and make appropriate allowances.

The stages of emotion testing

Why stages are useful

In order to learn the process of emotion testing it is useful to break it down into stages. This enables the practitioner to understand the order of the different parts of the test, which activities need to be carried out at different times and the purpose of these different activities.

Having stages to this process might suggest a mechanical and laborious process, but this is far from the truth. In fact the ‘stages’ help practitioners who are learning how to test emotions and also enable more experienced practitioners to improve what they are already doing.

Emotion tests can take minutes, but equally they can occur in seconds, simply because the mind can recognise patterns in an instant and respond in a second. Testing an emotion can be compared to the process of telling a joke. Joke-telling also occurs in stages, like getting people’s attention, introducing the characters, right down to the punch-line. Yet a witty remark can be delivered in a second.

The stages of emotion testing

The stages of emotion testing are:

• rapport

• creating or recognising opportunities to test

• choosing the emotion

• setting up the test

• delivering the test

• evaluating the response

• notating the response

Rapport

A good level of rapport is essential when testing emotions. The degree to which a patient will reveal her or himself to the practitioner is in direct proportion to the level of rapport achieved. Patients are being asked to respond genuinely from the inside and to do this it is essential that they trust the practitioner. Without this trust patients will not normally show themselves, especially any of their painful emotions.

Creating or recognising opportunities to test

Sometimes opportunities present themselves. At other times practitioners need to generate them. For example, in order to determine if a patient has reasonably balanced anger, it is useful to be discussing some event where the patient was frustrated. Frustration tests the ability of a person’s Wood Element to make new plans when previous ones have been thwarted. For each emotion, there are some events that can easily lead to a ‘test’ situation. These are referred to in Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8, listing the testing process for each Element under the heading ‘Opportunity’.

| Opportunity | Practitioners can test anger if patients raise an issue where they have been ‘abused’ in some way. They may have been frustrated, or feel themselves to have been treated badly by someone else or by some organisation. This does not need to be anything extreme. |

| Criteria for a workable test |

1. There is an abuse.

2. The abuse must be recent or ongoing.

3. There must be someone who committed the abuse – a person is best, an organisation is not so good, God or nature cannot be used.

4. There is some ‘wrongness’ to the abuse. This may be to do with things such as social norms, fairness or an agreement. For example, someone reneged on a promise.

|

| When to test | When the person is talking about the abuse, but is not manifesting much anger about it. The practitioner may notice some signs of minor discomfort but no overt anger or annoyance. If the person is already angry, do not test the anger – observe only. |

| How to test | Having listened to the patient talking about the abuse, the practitioner expresses a feeling of anger on the patient’s behalf by making a statement such as ‘You must have been angry at X.’ The words are accompanied by the practitioner’s non-verbal expression of an appropriate level of annoyance. |

| Emotion | Practitioners should express their own feelings with an appropriate amount of anger through emphasis in the voice and facial tightening. |

| Evaluation | A patient with a reasonably balanced Wood Element will show some anger. This may be evidenced by a shift in posture or a more clipped tone of voice. The expression of the emotion will be appropriate in intensity and smooth in flow. A person who has a chronically imbalanced Wood Element will often deny the anger – possibly by changing the information or by saying that there’s no point in doing anything about the ‘abuse’. Alternatively the expression of anger will be more than expected or it may be jerky and/or held in and it will not flow smoothly. |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can give patients a compliment or personal warmth when they arrive. Alternatively the practitioner can test joy when patients are remembering recent events normally associated with pleasure and joy or are anticipating joyful events in the future. |

| Criteria for a workable test | The patient is emotionally available, not taken up with other feelings. |

| When to test | At almost any time that the patient is not already experiencing joy or pleasure. It is important to take the person from a relatively neutral state. |

| How to test | The practitioner expresses congruent and sincere warmth and admiration for the patient, for example, by saying, ‘You look well today’ or ‘That’s a lovely jumper.’ Alternatively the practitioner may ask the patient about something pleasurable she or he has done recently or may do in the future. The practitioner may encourage this with appropriate joy and by saying for example, ‘Mmmm, that sounds great!’ Once the warmth has been given, the practitioner’s expression of the emotion must stop and the practitioner then observes the patient’s response. |

| Emotion | When practitioners share in the joy, they are feeling joy themselves and show this through their facial expression, posture and gestures. |

| Evaluation | With a healthy Fire Element, the patient can ‘hold’ the feeling of joy when the practitioner stops expressing it. The joy can rise and fall away again smoothly. If the Fire Element is chronically imbalanced the joy will drop suddenly (and not smoothly). Alternatively it may rise up into excessive joyfulness that doesn’t drop away. If the patient fails to become joyful this is also a sign of an imbalanced Fire Element. |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can test sympathy if the patient has run into difficulties, encountered frustrations or is having a difficult time. This can be when a patient is describing her or his main or secondary complaint. |

| Criteria for a workable test |

1. The patient should have a complaint that is recent or ongoing.

2. It should be something the patient cannot easily change or, at least, the patient should be clear that if they do anything about the problem, it will create even more problems.

3. In order to be authentic, the practitioner must accept that the complaint is in some sense justified.

|

| When to test | Whenever a complaint or difficulty is being discussed. |

| How to test | The patient tells the practitioner of the problem or complaint and the practitioner then gives the patient some support or understanding by making a statement like, ‘Oh, I am sorry to hear that. That must have been very difficult.’ |

| Emotion | The sympathy must be appropriate and empathetic, not babyish or patronising. |

| Evaluation | When the patient accepts the practitioner’s sympathy, it may evoke a feeling of acknowledgement and being supported. A patient with a healthy Earth Element will take in and accept the sympathy but will not dwell on it or keep asking for more. If the Earth Element is imbalanced the patient may not seem to have really taken in or digested the understanding and may take it in and ask for more sympathy. Alternatively the patient may simply reject the sympathy/understanding and may even change the information the practitioner has given by saying, for example, that the problem isn’t really so bad. |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can test grief if the patient has recently lost something. This may be physical (a possession), emotional (a person) or mental (an ambition or belief). Alternatively the practitioner can use phrases which direct the patient’s mind back in time. For example, ‘When you look back over…’, or ‘When you think about how things used to be . …’ |

| Criteria for a workable test | The practitioner takes the patient back to remembering the good aspects of what they once had before the loss. The practitioner gets the patient to re-experience the previous good feelings and why what was lost was important. |

| When to test | When the patient is remembering how good it was to have whatever is now lost. |

| How to test | The practitioner ‘asks’ the patient to feel the loss using a statement like ‘It is sad that you don’t have that any more.’ At the same time the practitioner’s non-verbal expression – face, touch, tone, words and gestures – must be congruently coming from an inner state of loss. This ‘test’ puts the ‘previous satisfaction’ and ‘the awareness that it is gone’ side by side in the stage of the patient’s mind. |

| Emotion | It is important that the practitioner accesses grief internally, and, for example, is not obviously sympathetic. |

| Evaluation | If the Metal Element is healthy the patient will move into an appropriate intensity of grief and come out again. If the Metal Element is out of balance the patient is likely to choke or tighten in the chest/throat area to stop the feeling. Alternatively, although rarely, the patient may sometimes become temporarily overwhelmed by the intensity of the feeling. |

| Although respect is not in itself an emotion, giving respect can elicit unresolved grief (see Chapters 17 and 19, this volume). | |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can check out the patient’s ability to receive respect by asking them about a time when they had a struggle. This could be anything from adolescence, a divorce, financial problems, etc. The practitioner can then label a genuine positive inner quality, such as generosity, compassion or perseverance, that the patient has demonstrated, that enabled her or him to get through this situation. |

| Criteria for a workable test | The positive inner quality can be supported by what the patient has said. Ideally, the patient is not aware she or he has this quality. |

| When to test | Just after the moment the patient has described the difficulty. |

| How to test | The practitioner listens carefully to the person’s description of a struggle and formulates the patient’s positive inner quality. She or he then attributes the inner quality to the patient, for example, ‘It sounds as if, especially in those circumstances, you displayed great generosity of spirit’. If the patient appears not to take this in, or indeed they deny having this quality, the practitioner can attract the patient’s attention again (possibly by touching) and repeat back to the patient the factual things they said that support them having the positive inner quality. |

| Evaluation | If a patient has a healthy Metal Element, she or he can take the compliment in and feel pleasure in it. If the Metal Element is out of balance the patient may love receiving the compliment but may deny having the positive inner quality. They may change the information to diminish the quality or clench up or hold themselves tightly in the chest or throat area. |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can test fear when a patient describes a situation that would normally induce a degree of concern or fear for his or her welfare but she or he is demonstrating no fear at all. |

| Criteria for a workable test |

1. The practitioner has detected a possible threat or area that is of concern to the patient.

2. The patient thinks that there may be undesirable consequences that might occur as a result of the threat.

3. The patient believes that she or he has no control or limited control over whether the undesirable consequences occur or not.

|

| When to test | When the patient is discussing the threat, but showing very little indication of fear in their facial expression, voice tone or posture or gestures. |

| How to test | The practitioner listens to the patient’s account of the threat and then expresses some concern or fear. For example by saying, ‘Goodness, you must be nervous/frightened that X will occur.’ The practitioner may show most of the concern non-verbally. |

| Emotion | The practitioner’s internal state should be that of concern/fear. Her or his non-verbal expression of fear is very important: for example, there may be a slight pulling back of the upper body and a ponderous nodding of the head. |

| Evaluation | A normal response is for the patient to express some fear. An abnormal response is to express no fear. A common abnormal response is for the practitioner to see a flash of intense fear in the patient’s eyes that quickly disappears. |

| Opportunity | Practitioners can check out the patient’s ability to receive reassurance when she or he has some concerns about the future or is afraid. |

| Criteria for a workable test | The practitioner needs to know:

1. The threat.

2. What undesirable consequences the patient expects to happen as a result of the threat.

3. Some genuine information about the likelihood of these undesirable consequences really occurring or not occurring. This information can arise from many different sources such as medical tests, rumours, the fact the doctor didn’t say anything, old wives’ tales, superstition, articles in journals/magazines, what someone in the health food shop said, etc.

|

| When to test | When the patient has expressed what appears to be fear. |

| How to test | It is important that the practitioner listens to and then acknowledges the patient’s fear and does not belittle it. She or he then lists each ‘reason’ why the threat will not occur and lets the patient know about any other reassuring information. |

| Emotion | The reassurance should be given to the patient in a calm, thoughtful way. Frequently the opportunity to reassure is lost because the practitioner goes straight to, ‘Oh don’t worry, I’m sure it will be all right’, which seriously mismatches how the patient is feeling. |

| Evaluation | If patients have a healthy Water Element they show signs that they can hear and take in what was said and feel reassured. A patient with an imbalanced Water Element may show signs that they are unwilling to take the information in, for example, by turning away, shaking the head or speaking over what is being said. Or the patient may appear to take the information in, seem reassured, but return with another similar fear. |

At first, students think that opportunities to test occur only rarely and are difficult to create. With experience and by establishing a deep level of rapport with patients, they realise that more opportunities arise than they thought. They also realise that an opportunity to test grief may also be an opportunity to test sympathy, anger or another emotion. They can use the same event and simply nudge it in one direction or another, in order to elicit the emotion they feel they need to understand more. Once students understand what constitutes an opportunity, they can begin to create them (see Box 25.7).

Box 25.7

The following are some examples of how opportunities may be created by practitioners.

• When a patient comes in describing an experience they’ve had recently, such as a car accident, the practitioner can test a number of different emotions. For example, sympathy for the person’s bad luck, anger at another careless driver, fear that it could happen again. This requires some questioning on the part of the practitioner to elicit which aspect of the event that it is appropriate to test.

• Practitioners can refer to another person’s experience, for example, ‘I saw someone yesterday who always seems to be having bad luck (losing things, being threatened, generally having a hard time, etc.). Have you ever had a phase like that?’

• Another alternative is for the practitioner to rely on some people’s natural inclination to deny that things are good. For example, if the practitioner asks, slightly in jest, whether they have been having a perfect, totally blissful time, many people will deny this. It is then easy to elicit a few complaints that can lead to ‘tests’ for sympathy or anger.

Choosing the emotion

Practitioners are frequently presented with a situation in which more than one emotion could be tested. For example, a complaint by the patient may generate a choice of testing either anger or sympathy. After this has become apparent, there is a moment when the practitioner has to make a choice. The practitioner will then need to decide if all of the criteria for the test are in place. These are referred to in Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8 under the heading ‘Criteria for a workable test’.

Setting up the test

Once the practitioner has chosen an emotion, she or he needs to ensure that certain factors are present so that the patient can naturally experience the emotion. These are referred to in Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8 under the heading ‘When to test’.

Delivering the test

This is the verbal or non-verbal ‘request’ to experience the emotion, to get angry, feel respected, etc. In order to understand another person’s emotions it is important for practitioners to understand their own emotions and be able to access them. The delivery of the test requires that the practitioner carrying out the test expresses genuine and congruent emotion. The delivery must be short and then stop. Examples of how such requests might be made are given in Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8 under the heading ‘How to test’.

Evaluating the response

Practitioners are evaluating the patient’s response (especially non-verbal) in the first few seconds after the ‘request’. Hence alertness and concentration are essential. Making the judgement accurately requires a level of experience and wisdom about how people respond in different situations.

In order to have a balanced viewpoint it is also necessary for practitioners to be aware of their own emotions and which situations evoke intense or inappropriate emotions in themselves. This will allow them to judge whether the patient’s response is ‘normal’, ‘inappropriate’ or, as is sometimes the case, hiding another emotion which is close to the surface, but not easy to observe.

The aspects to observe during an emotion test are the fluency and the intensity of the change evoked when the emotion is felt. Examples of how these observations are made are in Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8 under the heading ‘Evaluation’.

Notating the response

As testing is carried out several times, it is important that the practitioner has a quick way to notate the type of test and the judgement about the patient’s response. Stopping at that moment to write for thirty seconds will appear odd to the patient and rapport can be lost.

One way to notate the emotion tests is for the practitioner to use abbreviations for the emotions, for example, ‘J’ for joy. If the patient seemed unable to express anger about a noisy neighbour, even when it was obviously appropriate, then the practitioner might record ‘A → no A’. Ideally the practitioner will add a few words which remind the practitioner of the incident, for instance, writing ‘noisy neighbour’ might be a sufficient reminder.

The overall judgement about a test can be complex. The practitioner is looking for which of the patient’s responses to the emotion tests are the least fluent and most disturbed. Most patients have one emotion that is markedly more imbalanced than the others. In others several emotions are inappropriately intense or frequently expressed and it can be hard to decide which one indicates the CF. These judgements require the practitioner to review several of the patient’s responses and compare them to what is a normal response. The practitioner also needs to compare the ‘lack of fluency’ from one Element to another. Good recording helps to develop the practitioner’s ability to make this judgement. These judgements are usually made intuitively and in milliseconds, so when the practitioner is learning, it is useful to carry out the process consciously and slowly.

The testing process for each Element

Table 25.2, Table 25.3, Table 25.4, Table 25.5, Table 25.6, Table 25.7 and Table 25.8 outline the basic processes for testing emotions. After a period of practice and experience and as the process becomes more automatic and unconscious, the practitioner will no longer need to follow this routine, but to begin with this outline may be useful.

Summary

1 Colour, sound, emotion and odour are the four key methods of diagnosis used in Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. If the practitioner finds at least three of these key areas pointing to an imbalance in an Element, then this is a strong pointer to the patient’s CF.

2 The emotion is the most important of these four key areas and the practitioner needs to take special care to assess the balance of patients’ emotions. The emotions are the internal causes of disease and the ability to detect the emotions that produce or inhibit movements of qi is crucial.

3 The practitioner may need to deliberately evoke a person’s emotions in order to gain a full understanding of how they are balanced within a person.