28. Diagnosis by touch

Chapter contents

Introduction223

Pulse diagnosis223

Feeling the chest and abdomen226

The Akabane test229

Introduction

Most of the methods of diagnosis discussed in this chapter involve touch. They are:

• pulse diagnosis

• palpating the three jiao or burners

• palpating the abdomen

• palpating the front mu points

• the Akabane test

These methods of diagnosis cover much of the ‘to feel’ aspects of diagnosis. This is the part of the diagnosis covered in the physical examination of a patient. Of these five areas, pulse diagnosis is by far the most important. Assessing the way the pulses respond during a treatment can be especially useful when diagnosing the CF. All of the other methods of diagnosis can indicate that an Element or Organ is significantly out of balance and can also support the CF diagnosis. They are, however, far less important in determining the CF.

Pulse diagnosis

The purpose and value of taking the pulses

Taking pulses by feeling the radial artery on the wrist is of one the most important diagnostic practices of Chinese medicine and practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture place enormous importance on it.

The main goals of pulse diagnosis are to:

• assess the level of qi of an Organ and Element

• determine whether the qi of an Organ or Element is excessive or deficient, thus governing the needle technique used

• help to diagnose any blocks to treatment (see Section 4, this volume)

• assess changes in the patient’s qi during and after treatment

How to take the pulses

The position of the pulses

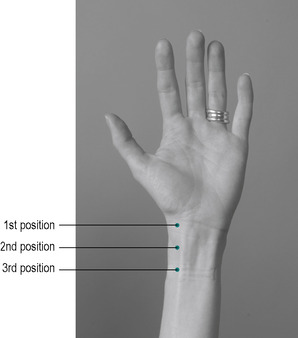

The pulses are felt on both wrists in three positions along the radial artery. The styloid process of the radius (shown in Figure 28.1) lies opposite the middle pulse position.

|

| Figure 28.1 • |

Position of the patient

When having their pulses taken the patient should:

• be relaxed, sitting or lying down

• have the arm free of obstructions such as watches, bracelets or tight sleeves

• have the arm level with, but no higher than, the patient’s heart

Position of the practitioner

When taking pulses the practitioner should:

• start by taking the pulses on the patient’s left-hand side, then the right

• stand at right angles to the patient and hold the patient’s left hand in their left hand as if shaking hands

• stand comfortably with a relaxed posture, weight evenly distributed and head held upright

Taking the pulses

When taking the patient’s pulses the practitioner goes through these stages:

• First, place the middle finger over the radial styloid until the tip reaches the radial artery. 1 At the same time use the thumb as a fulcrum at the back of the wrist.

1The use of the tip of the finger is probably a Japanese influence (see Eckman, 1996, pp. 206–207). Other traditions locate the pulse positions in the same place. They may, however, not hold the hand with the one that is not feeling the pulse and they may use the pads of the finger rather than the tips

• Next, let the middle finger drop on to the pulse of the middle pulse position.

• Having located the middle position, feel the first, second and third positions in turn. The first pulse position is distal to the middle position and is felt under the tip of the index finger. The third position is proximal to the middle position and is felt under the tip of the ring finger. When feeling each position, the practitioner should place only one finger on the artery at a time.

The two levels and the position of the Organs

The pulse is felt at two levels, superficial and deep. The superficial level is at the top part of the artery and is felt using light pressure. The deep level is lower down and is felt by using slightly heavier pressure. These two depths reveal the qi of the twelve yin and yang Organs. Table 28.1 shows the Organs in relation to the twelve positions.

| Left arm | Right arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Deep | Deep | Light | |

| Distal | Small Intestine | Heart | Lung | Large Intestine |

| Middle | Gall Bladder | Liver | Spleen | Stomach |

| Proximal | Bladder | Kidney | Pericardium | Triple Burner |

At different times in the history of Chinese medicine, slightly different pulse positions have been used (for a discussion of these, see Birch, 1992, pp. 2–13; Hammer, 2001, pp. 17–29; Maciocia, 2005, pp. 354–355 and Scott, 1984, pp. 2–7). Practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture use the positions laid down in the Nan Jing. Classical Chinese texts from the traditions of herbal medicine generally place the Kidneys at the third position on the right hand. Contemporary Chinese acupuncture texts usually place Kidney yang in the rear right-hand position, but this is a more modern (post 1949) development (see Birch, 1992, for a fascinating piece of research into the history of the placing of pulse positions in 101 different texts drawn from different periods in history).

Notating the quantity

Traditionally pulse diagnosis has determined the presence of up to 28 different qualities. Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturists focus on two, which are excess (full) and deficiency (empty). (Again, see Eckman, 1996. This emphasis on deficiency and excess is also a Japanese influence.) The overall fullness or emptiness is notated by using a numbering system ranging from −3 to +3 against the individual positions. Table 28.2 is an example of notating the pulses in this way.

| Left arm | Right arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Deep | Deep | Light |

| −1 | −1 | −1½ | −1½ |

| +1 | +1½ | ✓ | ✓ |

| −2 | −2 | −3 | −3 |

Feeling the quantity

When taking pulses the practitioner learns to discern the differences in strength between the different positions. At first the student concentrates on feeling the main differences, for example, the left middle position may feel stronger than the right middle position or the right first position may feel weaker than the right third position. After some experience has been gained by measuring this comparative strength, the practitioner attempts to find a ‘norm’ for the person.

The ‘norm’ in pulse taking

In order to find the patient’s ‘norm’, the practitioner considers the patient’s age, sex, physique and physical activity and decides on the level of strength that is a ‘✓’ or ‘just right’ for that individual. The norm for a young and strong person will be higher than that of an older and less strong person.

Having decided on the norm, the practitioner then records the pulses in relation to it. Some of the patient’s pulses may be stronger or weaker than the norm, so it is important that the practitioner bears in mind the level of the norm throughout pulse taking. Although this process is subjective, it has a sound basis in most practitioners’ experience. Almost all practitioners using any style of acupuncture will have experienced feeling a patient’s pulses and being surprised by their weakness or strength. This indicates that the practitioner has unconsciously decided on a norm. This is an important part of the diagnosis as most practitioners then look for an explanation for any apparent discrepancy.

Pulse changes during treatment and the overall change

So far the description of pulse diagnosis has outlined how practitioners can read the strength of individual pulse positions. Pulse taking in this way is crucially important because it reveals the strength of the qi in the Organs. There is also another reason for taking pulses, however. This is to consider the overall change that takes place in the pulses. This method is invaluable for both diagnosis and the evaluation of a treatment.

The overall view of the pulses

In order to feel this overall change in the pulses, the practitioner concentrates on how the different positions relate to each other. In this case the ideal is that the pulses are harmonious. Balance and harmony are more important than increasing the strength of an individual pulse position or even all the pulses.

When considering the notion of ‘harmony’, the practitioner will look for:

• the different pulse positions being similar in strength

• the different pulse positions being similar in quality

• similarity on one side of the pulses to those on the other

• clarity of the pulses or easy readability

Feeling for this overall harmony suggests that although Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturists are not directly taught to recognise pulse qualities, they are still indirectly feeling them when making these comparisons.

‘Clarity’ arises as an issue when practitioners find it difficult to specify that a pulse is − or + in quantity or the boundaries of a pulse seem ‘fuzzy’ and less precise than usual. After treatment, the pulse or pulses should change and become clearer.

Thus defined, harmony is a complex overall quality. With experience practitioners recognise it and make a judgement that the treatment has brought about greater or lesser harmony. It is a common experience for a Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist to treat a patient on the CF and then return to the pulses to find that they have become overall much more harmonious.

When practising Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture, the practitioner needs to recognise this feeling of greater harmony and use it as a standard for having carried out an effective treatment.

There is another important aspect to feeling pulse changes. When practitioners feel the pulses change to become more harmonious and a better quality, they may look back to remember what the pulses were like before the change. Making this before-and-after comparison enables practitioners to recognise pulse qualities that are not quite right more quickly, rather than noticing them only in retrospect, after a pulse change.

The CF pulse change

During the first few treatments, the practitioner concentrates on confirming the patient’s CF. For instance, the practitioner may have diagnosed the patient as a Fire CF. The diagnosis is only confirmed, however, when the patient is showing clear signs of improvement. Ideally, the diagnosis is confirmed by the beginning of the second treatment, but it often takes longer. An intermediate stage, which suggests that the diagnosis is correct, is achieving a ‘CF pulse change’.

The pulse change that is felt when the patient is treated on the correct Element of the CF has two characteristics.

• Firstly, all of the pulses change by becoming more harmonious, a better quality and often stronger. This overall change is crucial as it indicates that the condition of the other Elements is dependent on the health of the Element being treated.

• Secondly, the pulse positions associated with the CF may hardly respond at all or may even feel weaker.

At first these changes seem counter-intuitive, but they can be explained. The explanation is that the chronic imbalance of the CF is keeping the other Organs from performing well. As soon as the CF is treated, the other Organs can immediately respond. In the case of a Fire CF, the Earth pulses may feel very deficient because Earth has not been adequately nourished by Fire along the sheng cycle. Nothing is wrong with the Stomach and Spleen that treating the long-term imbalance, caused by the Fire CF, will not cure.

The CF pulse change is a valuable indicator when confirming the CF and evaluating whether treatment has been sufficient. During the course of treatment it is important to monitor the pulses to see which Elements respond well to treatment on the CF and which do not. For example, a patient may be a Metal CF and the Water and Wood Elements are also extremely imbalanced. The pulses of the Water Element may respond well to treatment on the Metal CF. Due to the patient’s excessive alcohol consumption, however, the pulses of the Wood Element do not respond so well. This may indicate that the Wood Element needs to be treated directly.

Pulse diagnosis can also be important when diagnosing and treating blocks to treatment especially a Husband–Wife imbalance or an Entry–Exit block. For more on this, see Chapters 32 and 33.

Feeling the chest and abdomen

Introduction

There are three methods of diagnosis that involve feeling the torso. The first is the assessment of the three jiao (or burners). The three jiao were discussed in the section on the Fire Element and the Triple Burner. The second is abdominal diagnosis involving palpation of various locations on the abdomen. The third is the palpation of the front ‘mu’ or ‘alarm’ points. To some degree these methods overlap and can be carried out in one process.

The three jiao

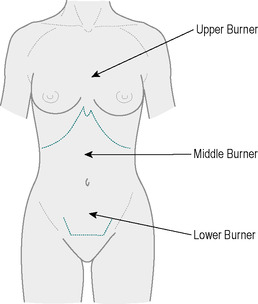

The torso is divided into three ‘burning spaces’ (see Figure 28.2). These are:

|

| Figure 28.2 • |

• the Upper Burner – which is situated in the chest and lies above the diaphragm. It contains the Heart, Pericardium and Lung.

• the Middle Burner – which lies between the diaphragm and the navel. It contains the Stomach, Spleen, Liver and Gall Bladder, and joins the Lower Burner at the navel.

• the Lower Burner – which lies below the navel. It contains the Small and Large Intestines, Bladder and Kidney.

The purpose of assessing the jiao

The three burners are assessed visually and by touch in order to:

• assess the warmth and strength of the qi in each burner

• determine if moxibustion or warming needs to be a significant part of treatment

• assess the progress of treatment

• assess how the patient reacts to physical contact

Feeling the three jiao

In order to feel the three jiao, the patient should lie down on the treatment couch. She or he is covered with a sheet or blanket in such a way that the areas can easily be exposed.

The practitioner stands to one side of the treatment couch and uncovers each jiao. The practitioner then places the flat of the hand across each burner, paying attention to its temperature. When feeling the Upper Burner, the middle of the hand should lie over Ren 17 to 18. For the Middle Burner it should lie over Ren 12 and for the Lower Burner Ren 5 to 6. On the Upper Burner the hand should be placed lengthways between the breasts on a woman and horizontally across the chest on a man. The locations are approximate.

A woman in her early fifties came for treatment because she coughed up copious amounts of phlegm every morning and occasionally vomited phlegm. She was an Earth CF and her middle jiao was very cold to the touch. On the first treatment, moxibustion as well as needles were used on Sp 3 and St 42, the source points of the Earth channels, and also on Ren 12. The middle jiao was immediately warmer. Over the next six treatments the practitioner used moxibustion consistently. The symptoms improved and the temperature of the middle jiao came much closer to the others.

Assessing the three jiao

When starting to feel the jiao it is useful for the practitioner to rank them from cool to warm or hot in relation to each other. With more experience, in a similar way to pulse diagnosis, the practitioner develops the idea of a ‘norm’ and can rate the burners as cold, cool, normal, warm and hot. Practitioners can use the method illustrated in the example below to record the temperature.

| −1 |

| ✓ |

| +1 |

The above record says that the middle burner is a normal temperature, the upper burner is cool and the lower burner is warm. ‘Warm’ implies that the jiao is warmer than it should be, as normal is the desirable temperature. The case study above illustrates how temperature can be used to assess a patient’s improvement.

Observing the jiao

When looking at the three jiao together, the practitioner may also touch the skin and flesh. This is not to feel the temperature, but to verify and support what she or he sees. The practitioner is assessing several aspects:

1 the colour of the different areas, for example, redness, darkness or paleness

2 the appearance of vitality or lack of vitality in different areas, for example, a water-logged lower abdomen

3 the structure of the area, for example, a tight and pinched rib cage

The observations should be recorded alongside the temperature findings

A male patient, aged 38, had been diagnosed as a Metal CF. His chest looked slightly sunken and his whole Upper Burner looked narrow, inert and pale. It also felt cool to the touch. In addition, the vertebrae from T2 to T5 were held tightly together. He commented that this area was often sore, especially after periods of stress and working on a word-processor. His arms appeared weak and any extended use, for example cleaning out his garage, left him feeling exhausted. This patient had treatment on and off over a 3-year period and one day his wife remarked that since having treatment his chest looked stronger and that it now appeared more normal.

Relating findings to the CF

Sometimes the assessment of the three jiao is unhelpful but at other times it is crucial. The Organs for Metal and Fire CFs lie in the Upper Burner. The Organs of Earth CFs relate to the Middle Burner and Water CFs to the Lower Burner. Wood CFs are more difficult to connect via the jiao. This is because the Liver Organ is clearly in the middle jiao, but some texts have attributed the Liver to the lower jiao.

Where there are abnormalities in the temperature, look or feel of the three jiao, these can sometimes be connected to the Organs of the CF. Abnormalities can also be useful when the practitioner is deciding whether to use moxibustion and helpful when assessing longer-term changes.

Abdominal diagnosis

The purpose

Practitioners carry out abdominal diagnosis by palpating various areas on the abdomen. By discerning the sensitivity and feel of these locations they then make inferences about the balance of the various Organs. This method of diagnosis originated in Japan and practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture give it considerably less emphasis than it is given by many Japanese acupuncturists. Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturists use this method of diagnosis only as a supplementary approach to other forms of diagnosis.

The locations on the abdomen

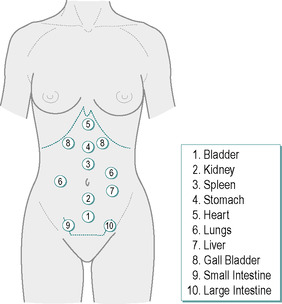

Figure 28.3 shows the locations to palpate. The relevant Organ is also indicated.

|

| Figure 28.3 • |

Carrying out the diagnosis

• The practitioner clearly explains the test to the patient. The practitioner should also reassure the patient that when palpating he/she will release the pressure if the patient indicates that the area is tender.

• The patient lies on the treatment couch with the abdomen exposed and the legs extended. The knees should not be bent.

• The practitioner stands beside the couch and initially observes the overall symmetry or lack of symmetry of the patient’s abdomen and the breathing.

• To palpate the areas, the practitioner uses the pads of the three middle fingers and presses down while the patient is exhaling. Pressure should be made firmly and slowly to a maximum of two inches or five centimetres.

• The patient gives the practitioner feedback by describing any abnormal, painful or just uncomfortable feelings.

• The practitioner records the patient’s response.

Responses to the palpation

The kind of responses the patient will give are that:

1 the area is painful and palpation should be stopped

2 there is some discomfort – which the patient can describe

3 the location is normal and is not tender

Although the patient’s feedback is important, with experience practitioners will also begin to notice other feelings of abnormality under their hand as they palpate. This will include feelings such as tension, flaccidity or lumps. The practitioner should also record these feelings. Ideally a patient has a pain-free response. Where there are abnormalities, this indicates that there is imbalance of some sort in the associated Organ. (It is useful to consult other texts about abdominal diagnosis, for example Denmei, 1990 and Matsumoto and Birch, 1993b, as the locations associated with the different Organs vary.)

Palpating the front mu or alarm points

Description and purpose

The front mu points are located on the chest or abdomen. There is one point associated with each Organ, although the points are not necessarily located on the channel of the associated Organ. These points have been called the ‘alarm’ points, suggesting that they are indicators of disease or imbalance. The translation of ‘mu’ is given as to ‘collect’, suggesting that the qi of the relevant Organ ‘collects’ at this point. (Maciocia gives alternative translations of ‘raise, collect, enlist, recruit’; Maciocia, 1989, p. 351.)

The points, unlike the areas used in abdominal diagnosis, are palpated as points, that is with one finger and using less pressure. When palpating these points the practitioner makes a note of any areas of tenderness.

The points

The points and their associated Organ are listed in Table 28.3. These points are not used for treatment in their capacity as front mu points, although many of these points may be used due to other indications (see Chapters 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 and 44 for more information on the use of the points).

| Organ | Alarm point |

|---|---|

| Lung | Lu 1 |

| Large Intestine | St 25 |

| Stomach | Ren 12 |

| Spleen | Liver 13 |

| Heart | Ren 14 |

| Small Intestine | Ren 4 |

| Bladder | Ren 3 |

| Kidney | GB 25 |

| Pericardium | Ren 15 |

| Triple Burner | Ren 7 |

| Gall Bladder | GB 24 or 23 |

| Liver | Liv 14 |

The assessment of the three burners, abdomen and alarm points can best be done as one process.

The Akabane test

Introduction

The origin and purpose

A Japanese practitioner, Akabane Kobe, devised this test sometime in the 1950s or 1960s. Its value lies in measuring the balance of the qi in the channels on one side of the body compared with the other. Practitioners usually assume that although the channels are bilateral, the qi of a channel overall is balanced. Akabane perceived that this is not always the case and his test was designed to measure the balance between the channels on the right and left sides. The test assumes that a channel with less qi is less sensitive to heat applied to a point on the channel.

Carrying out the test

To carry out the test:

• The practitioner locates the nail points of all the channels of the hands and feet. In the case of the Kidney, the point on the medial side of the little toe is used. This is opposite Bl 67.

• The practitioner lights a taper or Japanese incense stick. This is passed back and forth over the point on both the right and left sides.

• When carrying out the test, the patient’s finger or toe is held firmly by the practitioner with the hand not holding the stick. The hand that is holding the stick is stabilised close to the patient (see Figure 28.4).

|

| Figure 28.4 • |

• The practitioner moves the lighted end of the incense stick over the acupuncture point towards the nail and then away from it. The stick travels over a distance of approximately 0.7 centimetres, with the acupuncture point in the middle. The stick is moved at a constant speed as well as at an even distance (approximately 0.4–0.5 centimetres) from the skin. The even distance and speed is a crucial part of the test.

• The patient is asked to tell the practitioner as soon as they feel the heat. It is important that the patient says ‘hot’, having felt the same amount of heat on either limb.

• As the practitioner passes the lighted stick over the point she or he counts each pass as the stick travels back and forth. The practitioner must find a distance from the point so that the patient does not feel the heat immediately, but does feel it after five or more passes. The practitioner counts and records the number of passes needed on the channels of each side before they become hot.

Interpretation of the test

A significantly higher count on one side indicates that that side of the channel is relatively deficient in qi. For example, if the patient allows 12 passes over LI 1 on the right and only six on the left, then the right-hand side of the channel can be judged to be deficient.

A further test should be carried out on the channel or channels that are out of balance to check the result. If the result is consistent, then the imbalance can be corrected.

Correcting the imbalance

To correct this imbalance, the practitioner tonifies the luo-junction point on the deficient side (the side with the highest number). The test is then repeated and the ideal result is that the sensitivity to the heat is more closely balanced. If this treatment does not bring about the desired change, the yuan-source point of the deficient side is tonified.

If more than one channel is out of balance practitioners should notice if the imbalance follows the Organs of the sheng cycle. When correcting the imbalance, the first channel on the sheng cycle should be corrected first. The other imbalances may then correct by themselves.

Practising the Akabane test

This test and the subsequent treatment follow in the Five Element tradition of concentrating on balancing the patient’s qi. The test is only accurate, however, if it is carried out carefully and it requires much practice to ensure reliable results. When learning to do the test, it is important for several practitioners to test one person. This enables them to check that their findings are accurate. Practitioners do not need to count the same number of passes, but they should come to agreement about which channels are out of balance. Only when practitioners get consistent results should the test be used on patients.

Summary

1 Pulse diagnosis is carried out by feeling the radial artery on the wrist. It is of one the most important diagnostic practices of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture.

2 The main goals of pulse diagnosis are to:

• assess the level of qi of an Organ and Element

• determine whether the qi of an Organ or Element is excessive or deficient, thus governing the needle technique used

• help to diagnose any blocks to treatment

• assess changes in the patient’s qi during and after treatment, thereby evaluating the effect of the treatment

3 The three methods of diagnosis that involve feeling the torso are palpating the three jiao or burners, abdominal diagnosis and palpating the front mu points.

4 The Akabane test measures the balance of the qi in a channel on one side of the body compared to the other in order to ensure that the qi is balanced.