Chapter 1 Diagnosis and Treatment of Spinal Pain

Classifications of spinal pain

Low back pain (LBP) is defined as pain and discomfort that are localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds with or without leg pain. LBP is further defined according to the duration of an episode: acute, less than 6 weeks; subacute, between 6 and 12 weeks; chronic, 12 weeks or more (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Classification of Low Back Pain According to Duration of Episode

| Duration (Weeks) | Classification and Comments |

|---|---|

| <6 |

Nonspecific low back pain is defined as low back pain that is not attributed to recognizable, known, specific pathology (e.g., infection, tumor, osteoporosis, ankylosing spondylitis, fracture, inflammatory process, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome) (Box 1.1).

BOX 1.1 Three Categories (Or Diagnostic Triage) of Acute Low Back Pain

Chronic pain is defined as pain that:

The four diagnostic categories of LBP according to ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision) [1] in the absence of symptoms that suggest serious underlying disease (e.g., cancer, cauda equina syndrome, significant or progressive neurologic deficit, or other systemic illness) are as follows:

Table 1.2 Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain

| Diagnosis | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended | Not Recommended | |

| D1: Undertake diagnostic triage (serious spinal pathology, nerve root pain/radicular pain, or nonspecific low back pain), consisting of appropriate history and physical examination, at the first assessment. | T1: Give adequate information and reassure the patient. | T2: Prescription of bed rest as a treatment. |

| D2: Assess for psychosocial risk factors (yellow flags; see Table 1.3) and review them in detail if there is no improvement. | T3: Advise the patient to stay active and to continue normal daily activities, including work if possible. | T4: Specific exercises for acute low back pain. |

| D3: Diagnostic imaging tests (including radiographs, CT, and MRI) are not routinely indicated for acute low back pain. | T5: Prescribe medication, if necessary, for pain relief. | T6: Epidural corticosteroid injections for acute nonspecific low back pain. |

| D4: Reassess the patient whose symptoms fail to resolve. | T7: Consider spinal manipulation for patients who are failing to return to normal activities.T13: Consider multidisciplinary treatment programs in occupational settings for workers on sick leave for more than 4-8 weeks. | T8: “Back schools” for treatment of acute low back pain.T9: Behavioral therapy for treatment of acute low back pain.T10: Traction.T11: Massage as a treatment for acute nonspecific low back pain.T12: Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as a treatment for acute nonspecific low back pain. |

Diagnostic triage of acute LBP consists of the following conditions (see Box 1.1):

Red flags in the diagnosis of LBP are signs that a serious spinal pathology may be the cause of the LBP; they are listed in Table 1.3:

Table 1.3 Red and Yellow Flags in Diagnosis of Low Back Pain

| Red flags (signs of serious pathology) | |

| Yellow flags (psychosocial risk factors) |

Psychosocial yellow flags are patient factors that increase the risk for development or perpetuation of chronic pain and long-term disability (including work loss associated with LBP); examples are listed in Table 1.3. Identification of yellow flags should lead to appropriate cognitive and behavioral management.

Considerations for diagnosis

Advanced imaging studies should be performed only for the patient with the following findings:

Epidemiology of low back pain

Risk factors for LBP are poorly understood. The most frequently reported are as follows:

Outcomes

The aims of treatment for acute LBP are as follows:

Relevant outcomes for acute LBP are as follows:

Intervention-specific outcomes may also be relevant; examples are as follows:

Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain in Primary Care

The aims of treatment for acute LBP in primary care are to:

A General Assessment of Patients Reporting Low Back Pain

Relevant Medical History

Key elements of the patient’s medical history when symptoms of spinal pain are present (Boxes 1.2 to 1.4 and Table 1.4) are as follows:

BOX 1.2 Waddell Embellishment Tests That Indicate Nonorganic Pathology For Low Back Pain

Modified from Waddell G: 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences: A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine 1987;12:632-644.

Tests

| Question/Subject | Answer | Diagnostic Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Young | Disc injuries, spondylolisthesis |

| Middle age | Sprain/strain, herniated disc, degenerative disc disease | |

| Elderly | Spinal stenosis, herniated disc, degenerative disc disease, arthritis | |

| Pain: | ||

| Character | Radiating (shooting) | Radiculopathy (herniated disc, spondylosis) |

| Diffuse, dull, nonradiating | Cervical or lumbar strain (soft tissue injury) | |

| Location | Unilateral vs. bilateral | |

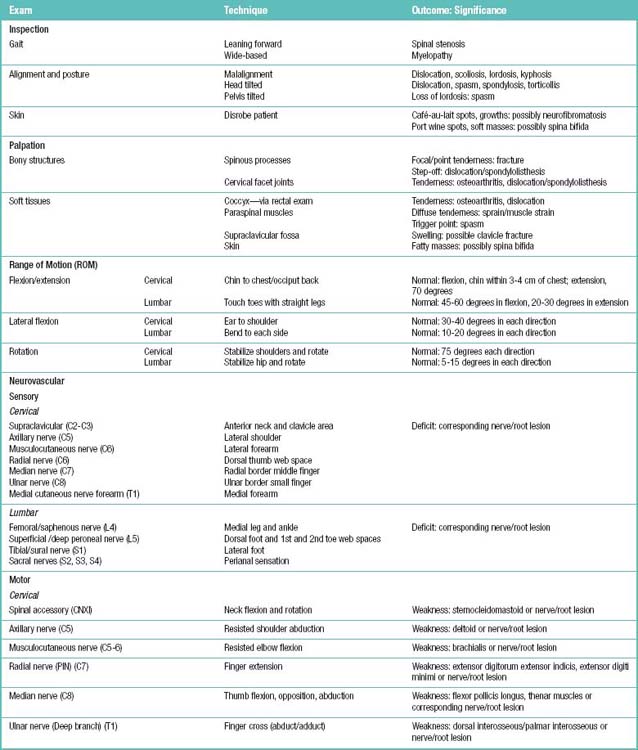

Physical Examination

A physical examination for patients with symptoms of spinal pain would include palpation for spinal tenderness, neuromuscular testing, and the straight-leg raise (SLR) test. Table 1.5 summarizes the examination, techniques, and their clinical application in the patient with a complaint of low back pain.

Neuromuscular testing should be performed to evaluate the following aspects:

Significant or progressive neuromotor deficit requires surgical consultation.

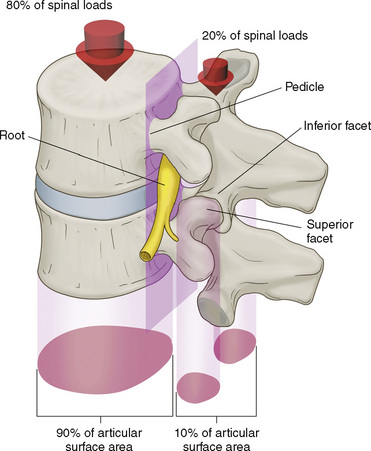

Related anatomy and physiology

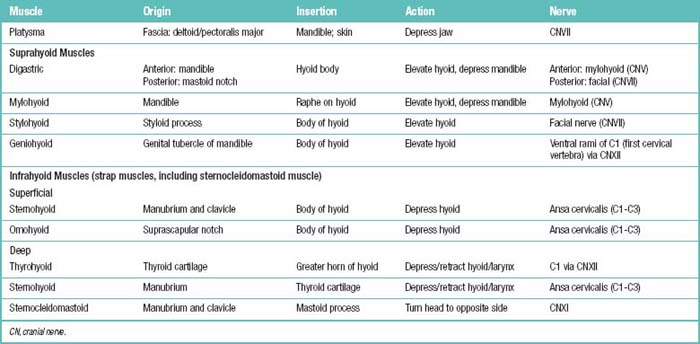

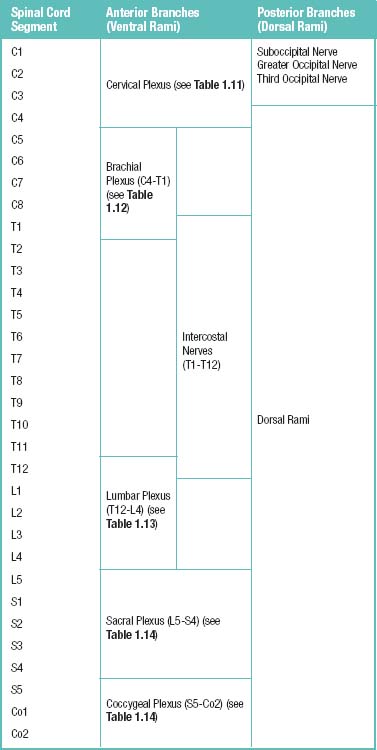

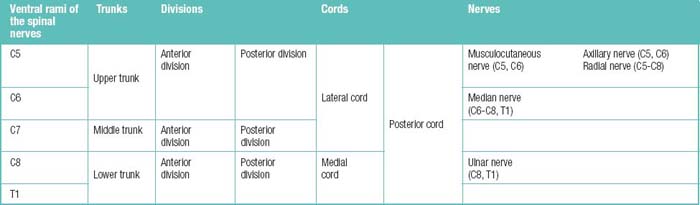

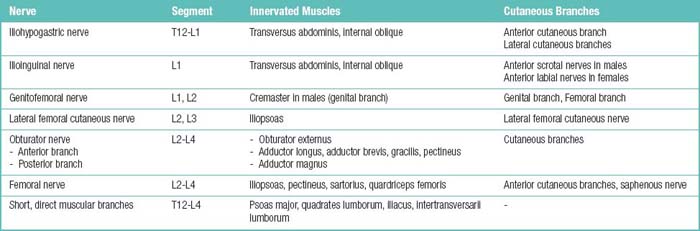

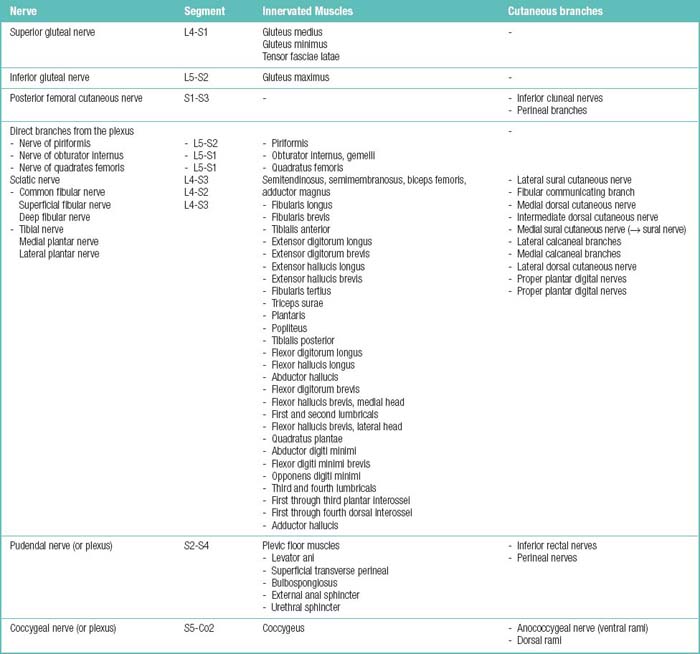

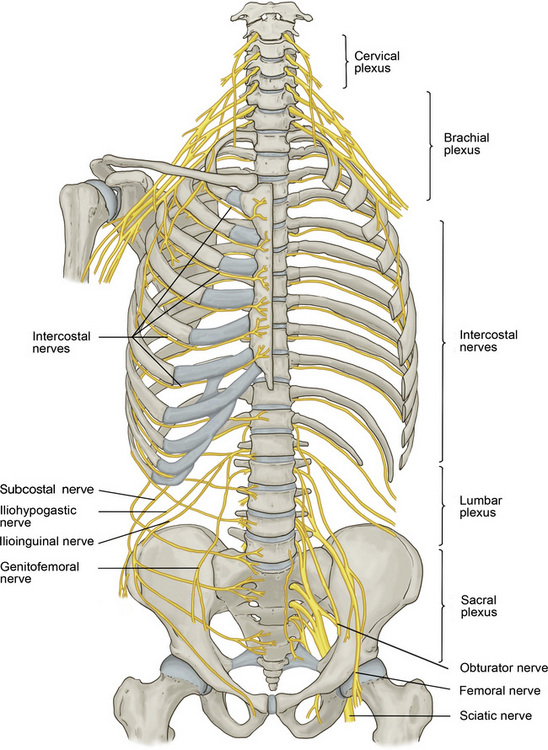

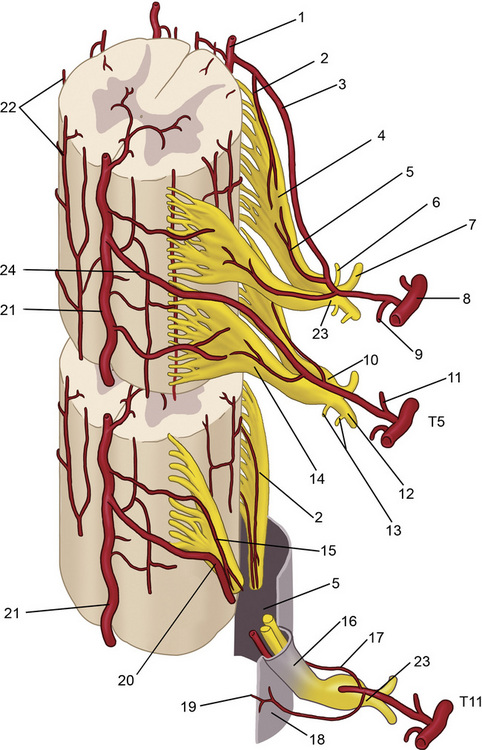

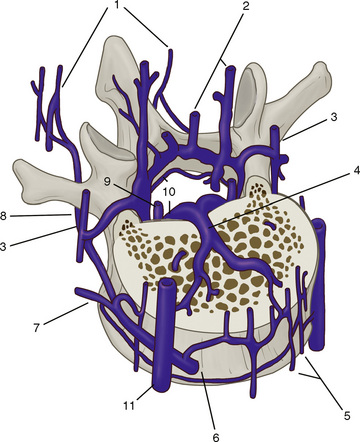

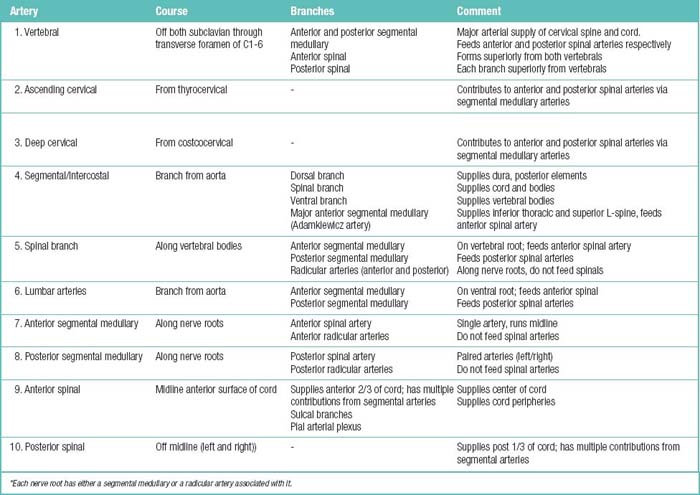

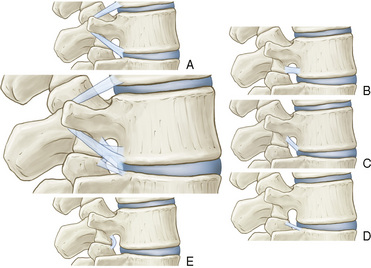

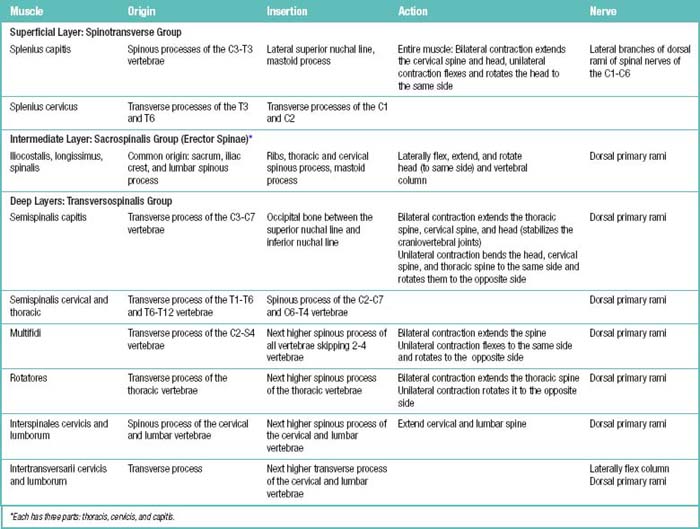

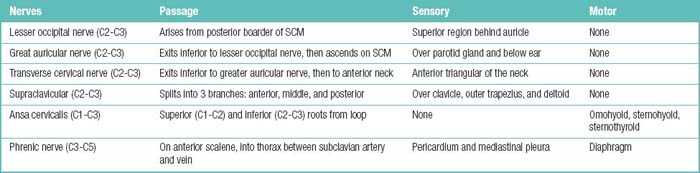

The spinal muscles on the neck and back are described in Tables 1.6 through 1.9. The spinal nerves are described in Tables 1.10 through 1.15 and shown in Figures 1-1 and 1-2. The spinal blood supply is shown in Figures 1-3 and 1-4 and described in Table 1.16. The intervertebral foraminal ligaments of the lumbar spine are shown in Figure 1-5.

Table 1.7 Posterior Neck Muscles (Suboccipital Triangle): Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

Table 1.8 Superficial (Extrinsic) Posterior Neck and Back Neck Muscles: Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

Table 1.9 Deep (Intrinsic) Posterior Neck and Back Neck Muscles: Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

Table 1.11 Cervical Plexus (C1-C4 Ventral Rami) behind Internal Jugular Vein and Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) Muscles

Table 1.15 Spinal Nerve Branches and the Territories They Supply

| Spinal nerve branch | Motor visceromotor territory | Sensory territory |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral ramus | All somatic muscles except for the intrinsic back muscles | Skin of the lateral and naterior trunk wall and of the upper and lower limbs |

| Dorsal ramus | Intrinsic back muscles | Posterior skin of the head and neck, skin of the back and buttock |

| Menigeal ramus | – | Spinal meniges, ligaments of the spinal column, capsules of the facet joints |

| White ramus communicans | Carries preganglionic fibers from the spinal nerve to the sympathetic trunk (‘White’ because the preganglionic fibers are myelinated) | – |

| Gray ramus communicans* | Carrries postganglionic fibers from the sympahetic trunk back to the spinal nerve (‘Gray’ because the fibers are unmyelinated) | – |

* Strictly speaking, the gray ramus communicans is not a spinal nerve branch but a branch passing from the sympathetic trunk to the spinal nerve.

Figure 1–2 Branches of the spinal nerves. Formed by the union of the dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) roots, the approximately 1 cm–long spinal nerve courses through the intervertebral foramen and divides into five branches after exiting the vertebral canal (see Table 1.15).

Imaging studies

The indications for and advantages of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) in the evaluation of low back pain are summarized in Table 1.17.

Table 1.17 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT): Indications and Advantages in the Evaluation of Low Back Pain

| MRI | CT | |

|---|---|---|

| Indications | ||

| Major or progressive neurologic deficit (e.g., foot drop or functionally limiting weakness such as hip flexion or knee extension) | Yes | Yes |

| Cauda equina syndrome (loss of bowel or bladder control or saddle anesthesia) | Yes | Yes |

| Progressively severe pain and debility despite conservative therapy | Yes | Yes |

| Severe or incapacitating back or leg pain (e.g., requiring hospitalization, precluding walking, or significantly limiting the activities of daily living) | Yes | Yes |

| Clinical or radiologic suspicion of neoplasm (e.g., lytic or sclerotic lesion on plain radiographs, history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, or systemic symptoms) | Yes | Yes |

| Clinical or radiologic suspicion of infection (e.g., end plate destruction on plain radiographs, history of drug or alcohol abuse, or systemic symptoms) | Yes | No |

| Severe low back pain or radicular pain that is unresponsive to conservative therapy and with indications for surgical intervention | Yes | No |

| Bone tumors (to detect or characterize) | No | Yes |

| Advantages |

Diagnostic interventional techniques

Evidence-based interventional diagnostic techniques for low back pain are as follows:

For an anatomic structure to be deemed a potential cause of back pain it must fulfill the following four criteria developed by Bogduk [2]:

The following three assumptions related to diagnostic use of neural blockade were developed by Hildebrandt [3]:

Ideally, a diagnostic block achieves block of the same structure three times as described below:

The minimum requirements for performance of diagnostic interventional techniques are as follows:

Contraindications to the performance of a diagnostic interventional technique are as follows:

The reliability and validity of any diagnostic technique are determined by the following factors:

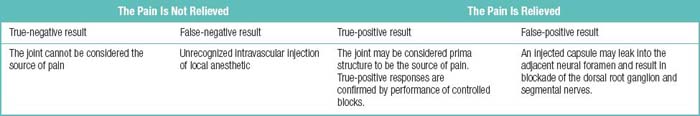

Facet or Zygapophyseal Joint Block

Diagnostic blocks of facet or zygapophyseal joint can be performed by anesthetizing the joint itself or the medial branches which supply the target joint with injections of local anesthetic, to test whether the joint is the source of pain (Table 1.18). If pain is not relieved, the joint cannot be considered the source of pain. If pain is relieved, the joint may be considered the primary source of the pain.

False-positive rates for diagnostic block of facet joints are shown in Table 1.19, in comparison with rates at which facet joints are actually the source of chronic spinal pain. The false-negative rate, which is 8% at all spine levels, is due to unrecognized intravascular injection of local anesthetic.

Table 1.19 Accuracy of Diagnostic Block of Facet Joints: False-Positive Rate versus Rate of Facet Joint–Caused Chronic Spinal Pain

| Region of Spine | Reported False-Positive Rates (%) | Rate for Confirmed Facet Joint–Caused Chronic Spinal Pain (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical | 27-63 | 54-67 |

| Thoracic | 55-58 | 42-48 |

| Lumbar | 17-47 | 15-45 |

Modified from Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004;5:15.

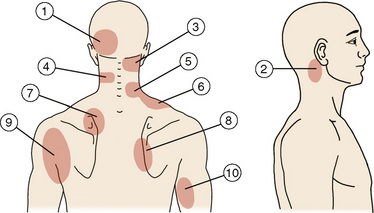

The rationale for using facet joint blocks for diagnosis is based on the following findings in normal volunteers (Figs 1-6):

| Source | Region |

|---|---|

| Joint | Main Region(s) of Pain Distribution |

| C0-C1 | 2 |

| C1-C2 | 2 |

| C2-C3 | 3 |

| C3-C4 | 3, 4 |

| C4-C5 | 4, 5, 6 |

| C5-C6 | 5, 6 |

| C6-C7 | 7, 8 |

| C7-T1 | 7, 8 |

| Dorsal Ramus | Region(s) to which Pain is Referred with Electrical Stimulation |

| C3 | 1, 3 |

| C4 | 4 |

| C5 | 5 |

| C6 | 7 |

| C7 | 7,8 |

(Modified from Fukui S, Ohseto K, Shiotani M, Ohno K, Karasawa H, Naganuma Y, Yuda Y. Referred pain distribution of the cervical zygapophyseal joints and cervical dorsal rami. Pain 1996;68:79-83.)

Provocative Discography

The overall accuracy of the various modalities of provocative discography is as follows [4]:

Transforaminal Epidural Injections or Selective Nerve Root Blocks

Sacroiliac Joint Blocks

Common sources of sacroiliac joint pain are as follows:

Therapeutic interventional techniques

The requirements for the performance of therapeutic interventional techniques in the spine include:

Minimum requirements in preparation for these procedures are as follows:

Contraindications to therapeutic interventional techniques in the spine are as follows:

Facet Joint Injections

The effectiveness of intra-articular injections, medial branch blocks, and neurolysis of medial branches for pain relief over the short or long term is shown in Table 1.20.

Table 1.20 Duration of Effectiveness of Therapeutic Interventional Techniques in Facet Joint Pain

| Modality | Short-Term | Long-Term |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-articular injection | ≤ 3 months | 3 to 6 months |

| Medial branch block | ≤ 3 months | 3 to 6 months |

| Neurolysis of medial branches | 3 to 6 months | > 6 months |

Epidural Injections

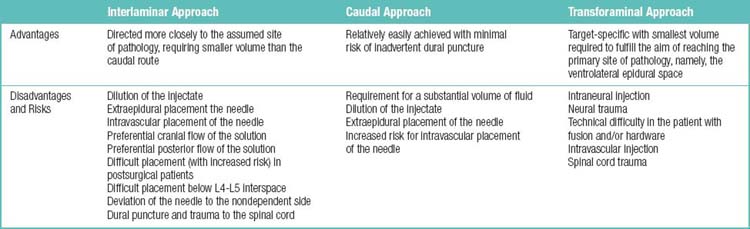

The three approaches for the epidural space are interlaminar, caudal, and transforaminal. The advantages and disadvantages of the three approaches are listed in Table 1.21. The known evidence for the short-term or long-term effectiveness of epidural injections is summarized in Table 1.22.

Table 1.22 Known Evidence for Effectiveness of Epidural Injections

| Type of Injection | Short-Term Effect (Significant Relief ≤ 3 Months) | Long-Term Effect (Significant Relief > 3 Months) |

|---|---|---|

| Interlaminar | Moderate evidence | Limited evidence |

| Caudal | Strong evidence | Moderate evidence |

| Transforaminal | Strong evidence | Strong evidence |

Epidural Adhesiolysis

The purpose and goals of percutaneous epidural lysis of adhesions are:

The known evidence for short-term or long-term effects of percutaneous epidural adhesions and spinal endoscopic adhesiolysis is summarized in Table 1.23.

Table 1.23 Known Evidence for Effectiveness of Percutaneous Epidural Adhesions and Spinal Endoscopic Adhesiolysis

| Percutaneous epidural adhesions |

Safety and Complications

The complications of percutaneous epidural lysis of adhesions are as follows:

Intradiscal Therapies

The known evidence for the short-term or long-term effects of epidural injections is described in Table 1.24.

Table 1.24 Evidence for Effectiveness of Intradiscal Therapies

| Intradiscal electrothermal therapy |

Implantable Therapies

Spinal Cord Stimulation

Brief history related to spinal cord stimulation

The mechanism of action of spinal cord stimulation occurs (1) at the local and supraspinal levels and (2) through dorsal horn interneuronal and neurochemical mechanisms. The indications for and contraindications to spinal cord stimulation are listed in Table 1.25. There is moderate evidence for long-term relief with spinal cord stimulation in a properly selected population with neuropathic pain.

Table 1.25 Indications for and Contraindications to Spinal Cord Stimulation

| Indications (for patients with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin and topographical distribution involving the extremities) |

Falowski S, Celii A, Sharan A. Spinal cord stimulation: an update. Neurotherapeutics 2008; 5: 86-99.

Implantable Intrathecal Drug Administration Systems

The advantages and disadvantages of implantable intrathecal drug administration systems are listed in Table 1.26. There is moderate evidence for long-term effectiveness of intrathecal infusion systems.

Table 1.26 Advantages and Disadvantages of Implantable Intrathecal Drug Administration Systems

| Advantages |

Medical decision-making – spinal pain

Treatment for spinal pain is medically necessary when the following conditions are met:

Activity recommendations for acute lower back pain

Activity Modification

Bed Rest

Exercise

A self-care brochure can be given to the patient to emphasize the following issues:

General decision-making process for chronic low back pain and sciatica

Chronic Low Back Pain

Lumbar spine radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral views) should be obtained if indicated. Oblique views are not recommended; they add only minimal information in a small percentage of cases, and they more than double the radiation exposure for the patient. Several radiographic findings are of questionable clinical significance and may be unrelated to back pain; they include the following [7]:

Chronic Sciatica

MRI and CT are not useful during acute sciatica unless there are red flag indications and the patient is a potential surgical candidate. In isolated cases of LBP without radicular symptoms, MRI is the preferred diagnostic procedure. However, in an otherwise healthy adult suffering LBP with radicular symptoms who has not undergone a previous back surgery, a CT scan may be as sensitive as an MR image (see Table 1.17).

Treatment of the painful motion segment

Diagnosis of radiographic cervical instability requires either of the following findings:

Indications for fusion of the degenerative spine are listed in Table 1.27:

Table 1.27 Indications for Fusion Procedures of the Degenerative Spine

| Procedure | Absolute Indications | Controversial Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical spine: | ||

| Anterior infusion Posterior fusion |

Bambakidis NC, Feiz-Erfan I, Klopfenstein JD, Sonntag VK. Indications for surgical fusion of the cervical and lumbar motion segment. Spine 2005; 30 (16 Suppl): S2-S6.

Indications for surgical decompression and fusion in the cervical spine are as follows:

Indications for cervical arthroplasty are as follows:

The advantages of lumbar interbody fusion over posterolateral fusion are as follows:

Potential indications for posterolateral lumbar fusion are as follows:

Potential indications for lumbar interbody fusion are as follows:

Table 1.28 compares posterolateral fusion with lumbar interbody fusion.

Table 1.28 Indications for the Selection of Posterolateral Fusion versus Lumbar Interbody Fusion

| Posterolateral fusion | |

| Lumbar interbody fusion |

Table 1.29 lists the relative contraindications to lumbar fusion procedures.

Table 1.29 Relative Contraindications to Lumbar Fusion Surgery

| Contraindication | To Posterolateral Fusion | To Lumbar Interbody Fusion |

|---|---|---|

| Multilevel (> 3 levels) degenerative disc disease (except in cases of spinal deformity) | x | x |

| Single-level disc disease causing radiculopathy without symptoms of mechanical low back pain or instability | x | x |

| Severe osteoporosis (possible subsidence of interbody grafts through the end plates) | x |

Table 1.30 lists the appropriate uses for interbody grafts (spacers).

Table 1.30 Uses for Interbody Grafts

| Type | Shape |

|---|---|

| PEEK (polyetheretherketone) interbody spacer | One boomerang spacer |

| Carbon fiber cage | One boomerang spacer |

| Titanium cages | Two small circular cages |

| One small circular cage | |

| One boomerang cage | |

| One elliptical cage | |

| Allograft | One “kidney bean–shaped” allograft |

| Two circular allografts | |

| Macropore spacer | One boomerang spacerOne or two circular or rectangular shaped spacers |

Wang JC, Mummaneni PV, Haid RW. Current treatment strategies for the painful lumbar motion segment: posterolateral fusion versus interbody fusion. Spine. 200; 30(16 Suppl): S33-43.

Table 1.31 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criterias for lumbar disc arthroplasty.

Table 1.31 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Lumbar Disc Arthroplasty Trials

Treatment guidelines for bone growth stimulators and lumbar fusion are as follows:

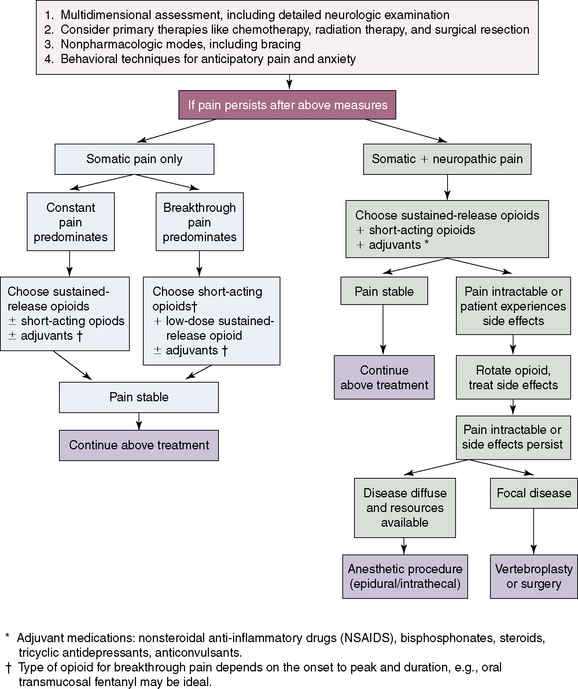

Cancer-related spinal pain

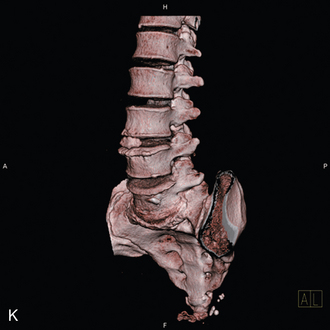

Figure 1-8 shows an algorithm for management of metastatic cancer–related spinal pain and the locations of primary neoplasms producing metastatic bone lesions are described in Table 1.32.

Table 1.32 Location of Primary Neoplasms Producing Metastatic Bone Lesions

| Primary Site | Number of Lesions (%) |

|---|---|

| Breast | 2020 (40) |

| Lung | 646 (13) |

| Prostate | 296 (6) |

| Kidney | 284 (6) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 255 (5) |

| Bladder | 160 (3) |

| Thyroid | 110 (2) |

| Total | 5006 |

From Herkowitz, HN, Garfin SR, Eismont FJ, et al : Rothman-Simeone: The Spine, 5th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2006, p. 1284.

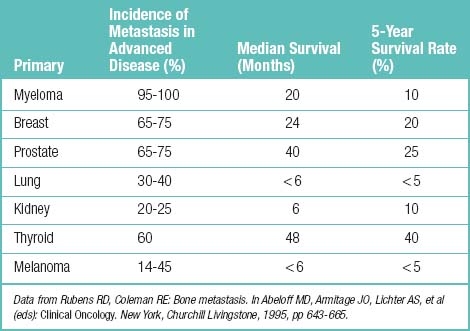

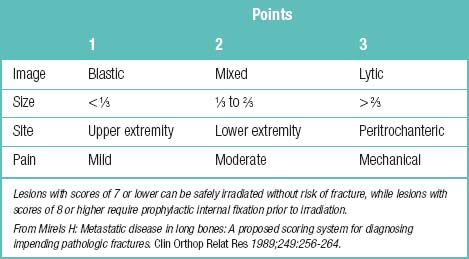

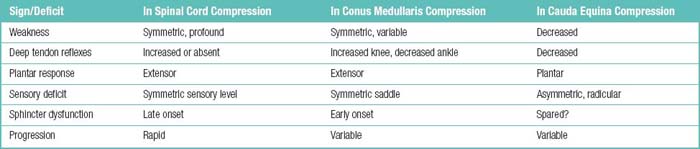

Other information for cancer-related spinal pain is summarized such as incidence and prognosis of bone metastasis (Table 1.33), radiologic appearance of metastatic bone lesions (Table 1.34), predicting the risk of pathologic fracture (Table 1.35), Karnofsky’s performance status (Table 1.36), signs of spinal compression (Table 1.37), categories of skeletal spinal metastasis (Table 1.38), and Tokuhashi’s scoring system for spinal metastasis (Table 1.39).

Table 1.34 Radiologic Appearance of Metastatic Bone Lesions

| Radiologic Appearance | Primary Lesion |

|---|---|

| Osteolytic | Lung, thyroid, kidney, colon |

| Osteoblastic | Prostate, bladder, stomach |

| Mixed | Breast |

Table 1.36 Karnofsky Performance Status

| Grade | Performance Level |

|---|---|

| 100 | Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease |

| 90 | Able to carry on normal activity; minor signs or symptoms of disease |

| 80 | Normal activity with effect; some signs symptoms |

| 70 | Cares for self; unable to carry on normal activity or to do active work |

| 60 | Requires occasional assistance, but is able to care for most of his or her needs |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistances and frequent medical care |

| 40 | Disabled, requires special care and assistance |

| 30 | Severely disabled, hospitalization indicated; death not imminent |

| 20 | Very sick, hospitalization necessary, active supportive treatment necessary |

| 10 | Moribund, fatal processes, progressing rapidly |

| 0 | Dead |

Table 1.38 Categories of Skeletal Spinal Metastasis

| Category | Severity of Skeletal Involvement by Metastasis |

|---|---|

| I | No major neurologic involvement |

| II | Involvement of bone without collapse and instability |

| III | Major neurologic involvement (sensory or motor) without significant bone involvement |

| IV | Vertebral collapse with pain caused by mechanical causes or instability but without significant neurologic impairment |

| V | Vertebral collapse or instability combined with major neurologic impairment |

Modified from Herrington KD: Metastatic disease of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:1110-1115.

Table 1.39 Tokuhashi’s Scoring System for Spinal Metastasis

| Characteristic | Point(s) |

|---|---|

| General condition (performance status, PS): | |

| Poor (PS 10-40%) | 0 |

| Moderate (PS 50-70%) | 1 |

| Good (PS 80-100%) | 2 |

| Number of extraspinal bone metastases foci: | |

| ≥ 3 | 0 |

| 1-2 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

| Number of metastases in the vertebral body: | |

| ≥ 3 | 0 |

| 1-2 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

| Metastases to the major internal organs: | |

| Irremovable | 0 |

| Removable | 1 |

| No metastases | 2 |

| Primary site of cancer: | |

| Lung, osteosarcoma, stomach, bladder, esophagus, pancreas | 0 |

| Liver, gallbladder, unidentified | 1 |

| Other Primary Sites | 2 |

| Kidney, uterus | 3 |

| Rectum | 4 |

| Thyroid, breast, prostate, carcinoid tumor | 5 |

| Palsy: | |

| Complete (Frankel A, B) | 0 |

| Incomplete (Frankel C, D) | 1 |

| None (Frankel E) | 2 |

| Current Trend In Treatment According to Total Score | |

|---|---|

| 0-8: ≥ 6-8 months (actual survival period) | Conservative treatment or palliative surgery |

| 9-11: ≤ 6 months (actual survival period) | Palliative or excisional surgery |

| 12-15: ≤ 1 year (actual survival period) | Excisional surgery |

Modified from Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, et al: A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumour prognosis. Spine 2005;30:2186-2191.

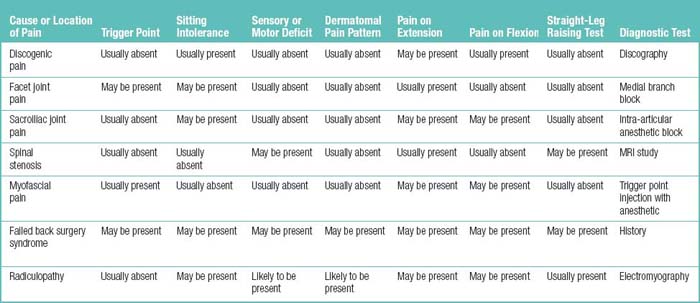

Differential diagnosis

Table 1.40 summarizes the differentiating features of the types and causes of low back pain.

1. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9.htm

2. Bogduk N. Low back pain. In Clinical Anatomy of Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, 4th ed, New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2005:183-216.

3. Hildebrandt J. Relevance of nerve blocks in treating and diagnosing low back pain—is the quality decisive. Schmerz. 2001;6:474-483. ? [in German]

4. Manchikanti L, Staats PS, Singh V, et al. Evidence-based practice guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2003;6:3-81.

5. Fraser RD, Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B. Discitis after discography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:26-35.

6. van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain in Primary Care: Chapter 3: European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl. 2):S169-S191.

7. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Adult Low Back Pain. Released 11/2008. Available at http://www.icsi.org/guidelines_and_more/gl_os_prot/musculo-skeletal/low_back_pain/low_back_pain__adult_5.html

8. Shealy CN, et al. Electrical inhibition of pain: experimental evaluation. Anesth Analg. 1967;46(3):299-305.

9. Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.