Diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes mellitus

Blood glucose

The diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes continues to be centred around glucose. Two measurements are widely performed: direct measurement of glucose itself, and glycated haemoglobin, a modified form of haemoglobin, the concentration of which is proportional to the prevailing glucose concentration over a period of time. It should be clear from the section on glucose metabolism and diabetes mellitus (pp. 62–63), however, that although many features of diabetes are related to hyper- and hypoglycaemia, it is, pathologically, a much wider metabolic disorder.

Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus

Criteria for diagnosis

The current World Health Organization criteria for diagnosing diabetes mellitus are shown in Table 32.1. The figures shown apply to the concentrations found in venous plasma; slightly different figures (not shown) apply to whole blood or capillary samples. Glucose is routinely measured in blood specimens that have been collected into tubes containing fluoride, an inhibitor of glycolysis. Because of the need sometimes to obtain rapid blood glucose results and the widespread self-monitoring of diabetic patients, blood glucose may also be assessed outside the laboratory using devices such as those shown in Figure 32.1. The fasting and 2-hour criteria define similar levels of glycaemia above which the risk of diabetic complications increases substantially.

Fasting blood glucose

A fasting blood glucose concentration of ≥7.0 mmol/L is regarded as diagnostic of diabetes, whether or not hyperglycaemic symptoms are present. The patient should be fasted overnight (at least 10 hours). If the result falls between 6.0 and 6.9 mmol/L, the patient is said to have ‘impaired fasting glycaemia’ (see below). Interpretation of fasting glucose results is shown in Table 32.1.

Table 32.1

Criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus

| Fasting blood glucose | ||

| Non-diabetic | Impaired fasting glycaemia | Diabetes |

| <6.0 | 6.0–6.9 | ≥7.0 |

| Oral glucose tolerance test | ||

| Fasting | 2-hour | |

| Impaired glucose tolerance | <7.0 | 7.8–11.0 |

| Diabetes | ≥7.0 | ≥11.1 |

All figures refer to glucose concentrations (mmol/L) in venous plasma.

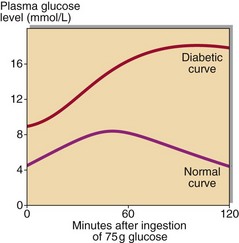

Other glucose measurements

Two other tests are still widely used, although their role in the diagnosis of diabetes is increasingly peripheral. The first is random blood glucose measurement, often performed opportunistically, particularly if a patient has hyperglycaemic (osmotic) symptoms like thirst, frequency and polyuria. A result of ≥11.1 mmol/L requires confirmation with a fasting glucose. The second is the oral glucose tolerance test (Fig 32.2). This was often done where diagnostic confusion still existed despite repeat glucose measurement, e.g. discrepant results from fasting and random blood glucose measurement. As the name suggests, the patient consumes an oral glucose load, with blood glucose measured (fasting) at the beginning of the test, and two hours later. The oral glucose tolerance test is difficult to standardise, and the correct procedure is often not followed. It is no longer widely advocated in the diagnosis of diabetes. However, the oral glucose tolerance test criteria for diagnosis of diabetes and of impaired glucose tolerance (see below) are included in Table 32.1 for completeness.

Current issues in diabetes diagnosis

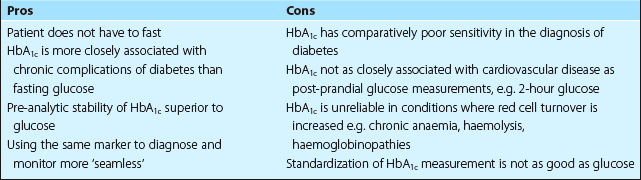

Increasingly, there are moves to use glycated haemoglobin measurements to diagnose diabetes as well as to monitor glycaemia. One of the reasons for this is that patients do not have to fast for glycated haemoglobin measurement, whereas they do have to fast for glucose-based measurements (apart from opportunistic random glucose). However, this proposal is controversial; some of the issues relate to the sensitivity and reliability of HbA1c. Many diabetes organisations around the world are beginning to recommend that HbA1c at least be considered as a potential tool to diagnose diabetes. Some of the pros and cons of glycated haemoglobin in the diagnosis of diabetes are summarized in Table 32.2.

Other

Most diabetic patients are taught how to monitor their own diabetic control. Home urine testing is the simplest form of monitoring and may be acceptable in patients with mild (early) Type 2 diabetes. If more accurate monitoring is required, patients may be supplied with a point-of-care glucose monitor (Fig. 32.1). This requires finger-prick whole blood samples (a drop is usually adequate); the patient is usually advised to vary the time of self-testing in order to get an overall picture of their glycaemic control.

Ketones in urine or blood

The term ‘ketone bodies’ refers to acetone and the keto-acids acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate. These are frequently found in uncontrolled diabetes (diabetic ketoacidosis or DKA – see p. 66). They are also found in normal subjects as a result of starvation or fasting, and sometimes in alcoholic patients with poor dietary intake (alcoholic ketoacidosis).