Chapter 7 Diagnosis and Management of the Patulous Eustachian Tube

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

A patient with a patulous or abnormally patent eustachian tube (ET) can experience symptoms that lead him or her to seek medical advice and possibly undergo surgery. This condition can be overlooked or mistakenly thought of as not having sufficient bearing on a patient’s quality of life to warrant efforts for its identification and correction. The ET has a pivotal role in the maintenance of proper volume and pressure homeostasis of the middle ear cleft, in expelling middle ear secretions, and in protecting the middle ear from reflux of sound and material from the pharynx.1 Dysfunction of the ET may be divided into two groups: dilatory dysfunction with failure to open the valve of the ET adequately, and patulous dysfunction with failure to close the valve adequately. This chapter addresses the diagnosis and treatment of an excessively open ET.

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF THE PATULOUS EUSTACHIAN TUBE

The ET is an organ composed of a skeleton made of cartilage and bone and associated muscles, fat, connective and lymphoid tissues, nerves, and blood supply.2 The normal ET is maintained at a closed resting position, and opens by voluntary and nonvoluntary maneuvers, such as swallowing; yawning; and deliberate manipulations of the palate, pharynx, muscles of mastication, and mandible. The tube may also open passively by changes in ambient air pressure or by forcing passage of air, such as with a Politzer maneuver.

As mentioned, tubal opening can be a by-product of movements initiated for other purposes (e.g., swallowing), but it can also be triggered by direct reflex stimuli. Gas is exchanged between the middle ear space, surrounding mucosa, and blood vessels. There is a net absorption of gas into the circulation; when the ET is closed, this causes an increasingly negative pressure beyond that of the normal resting pressure of the middle ear. The absorption rates of the constituents of air differ with nitrogen being the predominant gas, but having relatively slow absorption compared with oxygen and carbon dioxide. Therefore, the gas composition varies over time after each dilation of the ET. It is thought that deviation from the set-points of pressure and gas composition may be detected by a combination of baroreceptors and chemoreceptors that initiate the opening of the ET to convey air into the middle ear and re-establish homeostasis.3

Active opening of the ET usually lasts about 400 ms. It is the result of a coordinated effort of four muscles, the most important of which is the tensor veli palatini (TVP), laterally dilating the anterolateral membranous wall.1,4,5 Although the opening mechanism of the ET has been studied extensively, closing of the ET has received less attention. The part of the ET that is normally closed at rest and open on dilation is referred to as the valve. The valve constitutes the approximately 5 mm long segment of apposing mucosal surfaces within the middle of the cartilaginous portion of the ET.6 Closure of the ET is thought to be the result of the following factors: recoiling memory properties of the cartilaginous ET, relaxing bulk of the TVP muscle, and pressure of neighboring paraluminal tissue. The closed lumen is likely maintained by all of these factors, and aided by the surface tension of the apposed wet mucosal surfaces.

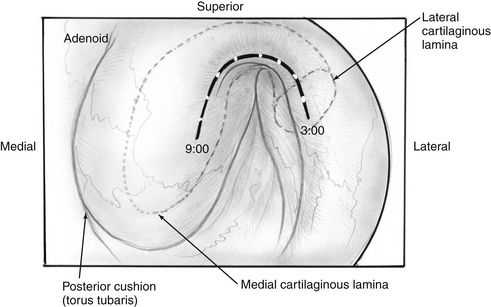

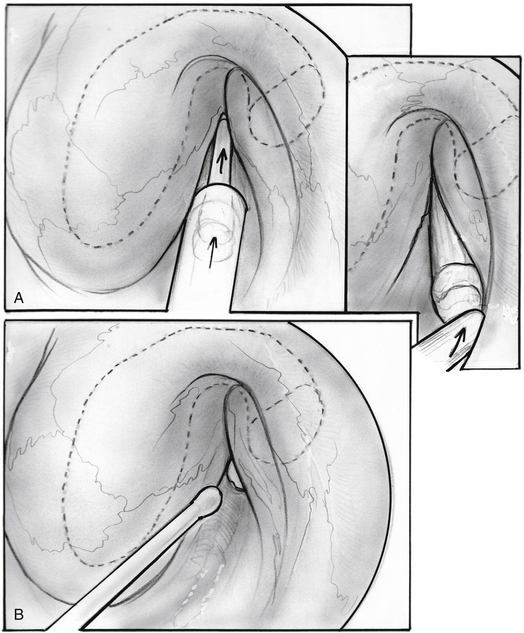

Transnasal endoscopy and surgery of patulous ETs has revealed that the underlying pathology is a longitudinal concave defect in the anterolateral wall of the valve (Fig. 7-1). This wall normally has a convex bulge into the lumen of the ET in the relaxed position. The defect represents a lack of tissue volume that can be a deficiency of the lateral cartilaginous lamina, Ostmann’s fat, TVP muscle bulk, submucosa, or mucosa. Examples of these deficiencies, either isolated or in combination, are seen in clinical cases. Temporary or permanent obliteration of the defect, even with some mucus, immediately relieves patients’ symptoms.

Because the cartilaginous backbone of the ET is open in its medial-anterior aspect, the lumen patency also depends on the pressure of the abutting soft tissues. The relaxed paratubal muscles (mainly the TVP) and Ostmann’s fat pad contribute to lumen closure. Glandular tissue and the size of Ostmann’s fat pad were found to be smaller in patients with a patulous ET compared with normal controls as measured by computed tomography (CT) scans.7 The mucosal and submucosal tissue layers increase in thickness as they are relieved of tension with muscle relaxation, and are in themselves a factor in closure of the valve. A report of fluctuating patulous symptoms in hemodialysis patients describing relief of symptoms during fluid retention and exacerbation after excretion showed the close connection between periluminal mass and symptoms of patulous ET.8

ETIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

An overly patent ET allows for the free passage of air and the sound it carries from the nasopharynx to the middle ear, creating a pathologic acoustic and pressure environment. The most prominent symptoms of a patulous ET are aural fullness and autophony of a patient’s own breathing noises and voice. Symptoms are mostly related to free passage of air and sound, but not reflux of material. Symptoms compatible with patulous ET have been described since the second half of the 19th century. The constellation of symptoms compatible with those seen in patients with patulous ET was reported by Jago in 1858,9 who later described his personal experience with the condition. Schwartze recognized the connection between the patulous ET and excursions of the tympanic membrane with respiration. Zollner and Shaumbaugh emphasized the important symptom of autophony in a series of patients with patulous tubes (as reported by Bluestone and Magit10).

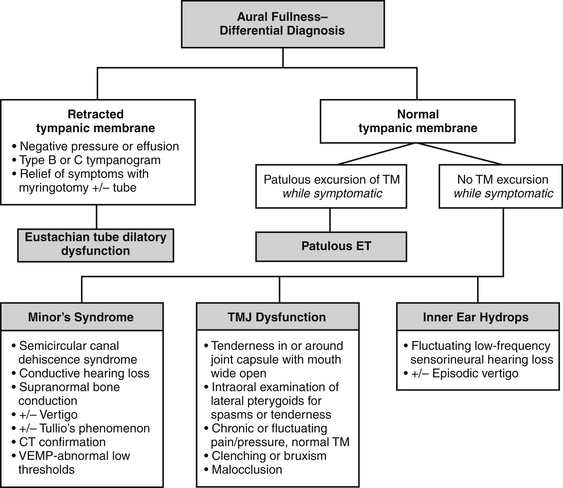

Aural fullness and the sensation of ear blockage can be misdiagnosed as dilatory dysfunction of the ET, especially because the patient usually describes the ear as “blocked.” The differential diagnosis for aural fullness also includes temporomandibular joint or related musculoskeletal dysfunction, Minor’s syndrome of semicircular canal dehiscence, and endolymphatic hydrops (see Fig. 7-3). Because of the typical complaint of “ear blockage,” many patients are initially treated with medications directed against dilatory dysfunction, such as nasal decongestants, steroid topical sprays, and topical or systemic antihistamines, all of which fail to help or even aggravate the symptoms.

The etiology for the loss of tissue creating a patulous ET is uncertain. Possibly associated factors such as weight loss and tissue atrophy from chronic disease account for only two thirds of the patients.11 Loss of tissue volume from within the tubal lumen is cited as the most common pathogenesis and most commonly reported with weight loss.12 Shea (personal communication, 2007) noted that one third of patients have a significant weight loss, and one third have some sort of rheumatologic condition. The authors’ experience has been similar.

Simonton13 grouped etiologies according to positive and negative contributing factors. Positive factors were defined as factors actively reducing tissue volume, such as with scarring from previous procedures, inflammation, and radiation.14,15 Negative factors were due to a passive loss of tissue around the pharyngeal orifice, loss of tonic action of the TVP muscle, and conceivably reduced coiling properties of the ET. Hormonal factors include pregnancy,16 high-dose oral contraceptives, and estrogen treatment for prostate cancer. Estrogen can reduce the viscosity of tubal secretions, reduce the elastic properties of the tubal cartilage, and elevate the level of surfactant via a change of prostaglandin levels. All these factors would support opening of the ET. Reflux of gastric contents and allergy were reported to be the cause in 3 of 11 patients in one series.17 Other contributors reported include abuse of nasal decongestants and cocaine, poliomyositis, multiple sclerosis and other neuromuscular disorders, cerebrovascular accidents, craniofacial abnormalities, temporomandibular joint malfunction, and malocclusion. Occasional association between patulous ET and palatal myoclonus has been reported.18 The habit of sniffing or Valsalva’s maneuver can be acquired in patients attempting to aerate their middle ears at times of otitis media, but may ultimately result in a patulous tube.

DIAGNOSIS

The improved inspection and manipulation of the nasopharynx brought about with the introduction of endoscopic sinus surgery tools greatly improved the ability to diagnose and correct patulous ET. High-quality endoscopy allows for direct and detailed examination of the ET valve. Done with either a rigid or a flexible endoscope, it may show a concave defect in the anterolateral part of the valve, instead of the normal convexity.19 The defect prevents normal closure of the orifice in the resting position, leaving a slitlike opening in the lumen of the orifice.

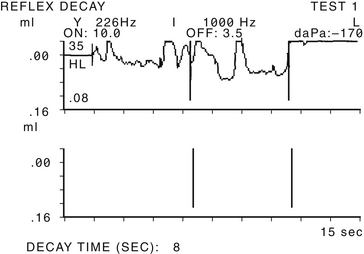

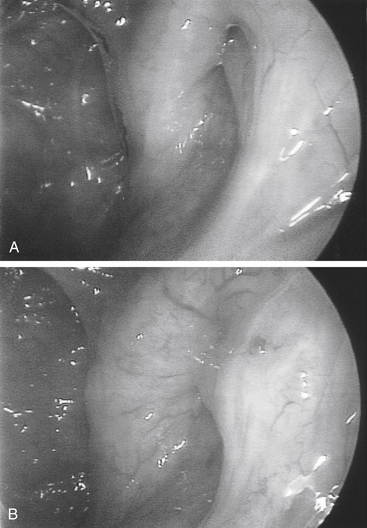

Ancillary tests may be of some assistance in the diagnosis of patulous ET. Impedance tympanometry while the patient experiences autophony may reveal fluctuation in tracing in line with tympanic membrane excursion (Fig. 7-2). Tympanometry can also record middle ear negative pressure or hypermobility of the tympanic membrane. Sonotubometry can directly measure ET patency.20,21 During the examination, a sound is emitted in the nasal cavity and is recorded by a microphone located in the external auditory canal of the examined ear. As the ET opens, the sound recorded in the external auditory canal intensifies, and an increase of 5 dB or more is considered to reflect opening of the ET reliably.22 Severity of subjective autophony was found to be correlated with objective measurements of ET function by sonotubometry.23 This test is not available routinely in the clinical setting. It has been suggested more recently to make use of this principle in performing audiometry masked by a nasally presented noise. In subjects with patulous tubes, thresholds of low tones were significantly elevated more than in normal controls because sound presented in the ear was masked by the noise escaping the nasal cavity to the middle ear through the patent ET. The thresholds normalized in most patients after corrective measures were taken.24

Imaging is not routinely used for the diagnosis of patulous ET. Until more recently, CT scanners required a recumbent examinee, a position that commonly results in closure of the patulous tube. The availability of scanners allowing examinations in the seated position has allowed researchers to record patency of the ET in resting and under Valsalva maneuver.25 Imaging-based measurements of a group of patients with patulous ETs were statistically significant compared with normal controls.

The other causes for aural fullness or ear blockage should be systematically considered (Fig. 7-3). ET dilatory dysfunction causes negative pressure in the middle ear or effusion that should be visible on otologic examination and tympanometry. Endoscopic examination reveals evidence of an obstructive problem with mucosal swelling or inflammation, or a dynamic disorder with failure of muscular dilation.19

The diagnosis of semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome, or Minor’s syndrome, must be considered before making a final diagnosis of patulous ET (of which most are dehiscences of the tegmen into the superior semicircular canal).26 These two very different pathologies can manifest with similar symptoms of autophony of the voice, but autophony of breathing sounds is much more pronounced in patulous ET.17 Differential diagnosis is made more difficult by the fact that superior semicircular dehiscence (SSCD) may manifest without vestibular symptoms.27 Older series of patients assumed to have a patulous ET most likely included patients who had Minor’s syndrome.

Almost 20 years before the first description of SSCD syndrome by Minor and associates,28 O’Connor and Shea14 described some patients thought to have patulous ET who experienced vertigo accompanied by nystagmus induced by a sharp increase in nasopharyngeal and intratympanic pressure. They attributed symptoms and signs to stapedial or round window membrane movement, although in retrospect, it is highly likely that the patients had Minor’s syndrome. Of the senior author’s series of patients with SSCD, 94% complained of autophony of their voice, and half of them found relief by placing their head in a dependent position.17 Relief of autophony while lying supine has long been thought to be pathognomonic for patulous ET, but changes with intracranial or intralabyrinthine pressure with the head dependent probably also influence the impedances of the dehiscences that cause Minor’s syndrome. Patients with Minor’s syndrome tend to have unremitting autophony when it becomes present, as opposed to symptoms of patulous ET, which are generally intermittent. Vertigo and nystagmus induced by sound or pressure, supranormal bone conduction, and conductive hearing loss with intact stapedial reflexes all should raise the suspicion of SSCD. The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of the bone dehiscence with high-resolution temporal bone scan reconstructed in the Poschel and Stenvers planes, and by lower than normal thresholds in Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential.

TREATMENT

When indicated, treatment is directed toward augmenting the periluminal tissue, specifically filling the defect in the valve. This can be done by adding bulk to the native tissue by inducing congestion or by introducing mass from other sources (autografts, allografts, xenografts, or synthetic implants). Numerous agents affecting the mucosal lining of the valve can be used with good, albeit temporary, results. In an off-label use, a conjugated estrogen preparation (Premarin) can be administered as a nasal solution resulting in mucosal edema.29 A dose of 25 mg of intravenous Premarin is diluted in 30 mL of isotonic sodium chloride to be taken as nasal drops three times a day. Side effects include epistaxis and nasal irritation. Saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), an expectorant designed to enhance viscosity of the mucus, is taken three times a day as 8 to 10 drops diluted in water or juice. Powder of boric and salicylic acid (4:1 ratio) insufflated to the nasopharynx or instilled with a catheter causes local irritation and edema offering temporary relief.12 Insufflation of mucosal irritants can also be used as a diagnostic test or temporary treatment for patulous ET. Some local irritants reported have included the application of silver nitrate, nitrate acid, and phenol.11,29 These irritants can also scar the mucosa and restrict the opening of the ET. Although many of these treatments brought about improvements in patients’ symptoms, the improvements were transient.

Surgical intervention is reserved for the few patients with symptoms significantly affecting their quality of life, when less intrusive methods of treatment fail. Myringotomy with the placement of ventilation tubes is probably the most common surgical intervention, reported to aid approximately 50% of patients.30 Ventilation tubes alleviate mostly symptoms related to middle ear pressure changes and tympanic membrane movements, but less so reflux of sound—autophony.17

Various materials have been injected in an effort to fill the orifice defect responsible for creation of patulous ET. In 1937, Zollner31 proposed infiltrating paraffin anterior to the ET orifice, in an attempt to recreate the missing mass abutting the orifice. Pulec12 reported only 1 patient out of 26 not helped by injecting polytef (Teflon) to the anterior part of the orifice; 19 patients had complete relief from symptoms after one injection of 0.75 to 1.5 cm3 of Teflon paste. None of the patients had otitis media after the procedure. The same material was used by O’Connor and Shea,14 who injected Teflon anterior to the orifice. Use of Teflon for this indication was discontinued because of complications, including cerebral thrombosis and death, possibly as a result of injection of Teflon into the immediately adjacent internal carotid artery. Ogawa and colleagues32 reported their successful, albeit short-lived, experience with injection of absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) mixed with glycerin to the lumen of the ET.

Brookner and Pulec33 studied a dog model and pointed to the anterior wall of the pharyngeal orifice of the ET as the correct location for augmentation. Injection of Teflon paste into this area resulted in an increased resistance in airflow through the ET without initiating otitis media. Injecting the posteromedial wall of the posterior cushion (torus tubarius) resulted in elevated resistance of the tube as well, but three of four injected dogs developed serous otitis media. Impediment of lymphatic flow was thought to be the likely cause of this side effect.

Complete blockage of the ET cures patients from symptoms of patulous ET, but usually results in the need for long-term or permanent ventilation tubes. Simonton13 reported partial success in three cases using conization of the ET cartilage and suturing the mucosa closed. Doherty and Slattery11 used circumferential electric coagulation and application of a fat graft to seal the tube successfully with symptomatic improvement in two patients.

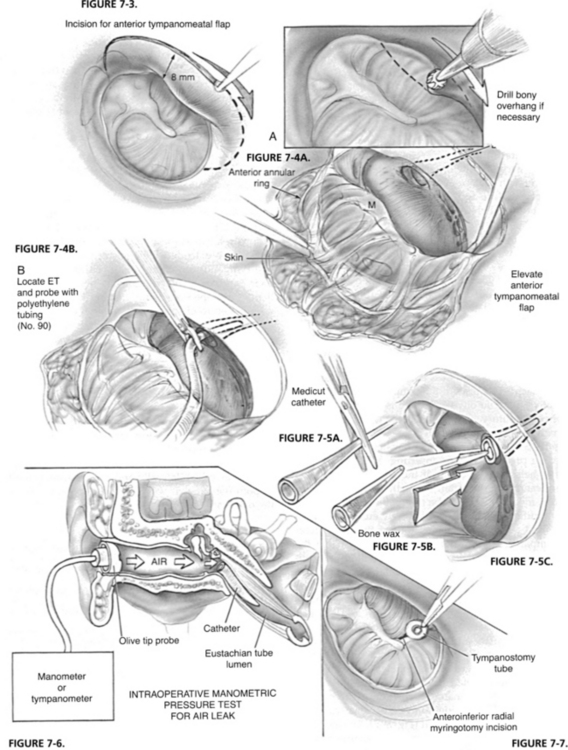

A different approach to obstruct the patent ET is by placing an intraluminal catheter. Plugging the ET with a catheter sealed with bone wax that was introduced through a tympanotomy or myringotomy approach resulted in long-term resolution of symptoms.34 An anteriorly based tympanomeatal flap was raised, and if required the bony annulus would be drilled to facilitate exposure of and approach to the ET orifice. An intravenous catheter filled with bone wax was introduced into the lumen of the ET through the middle ear. Nine patients, who failed previous medical and surgical interventions, were treated by insertion of an intraluminal catheter through the tympanotomy approach and placement of tympanostomy tubes, and were followed for 2 to 15 years. Six patients had marked improvement in symptoms. Two patients extruded their catheter and tympanostomy tubes, but still obtained relief of symptoms. Two patients extruded the tympanostomy tubes, and although the catheters were in place did not experience middle ear effusion, probably because of sufficient leak of air around the catheter.10

Intraoperative manometric measurement was employed by Bluestone1 with a tympanometer noting that opening pressure of the ET had been increased to 500 to 700 mm (Figs. 7-4 through 7-7). Shea Jr. and associates at the Shea clinic offer a similar transtympanic procedure: introducting of one or more Teflon catheters of various appropriate sizes. According to information available from the Shea clinic’s website www.sheaclinic.com, of 40 patients operated on, 90% were improved, and 5% were made worse; in 5%, the symptoms were unchanged.

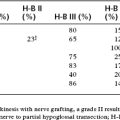

Release of the TVP muscle by transposing it medially to the hamulus relieved symptoms for at least 6 months in 9 of 10 patients undergoing this procedure.35 The incidence of postoperative otitis media was not reported. Virtanen and Palva15 published their experience with pterygoid hamulotomy. Release of the tendon of the TVP was supplemented at times with cutting its tendon if deemed necessary. Clinical relief was achieved in 11 of 16 of the operated patients, although sonotubometry recording normalized in only 9 patients.

TECHNIQUE OF TRANSNASAL AND TRANSORAL OCCLUSION OF THE PATULOUS EUSTACHIAN TUBE DEFECT

Repair of the patulous defect can be done less invasively through the nasopharyngeal orifice without tympanotomy (Figs. 7-8 through 7-14). An intravenous catheter can be inserted into the tubal lumen wedged into the isthmus, the narrowest segment of the ET for long-lasting relief of patulous symptoms while generally maintaining the patency of the tube when it dilates normally to the open position. The physiologic function of the ET can be preserved in most cases, while repairing the patulous defect in the valve.

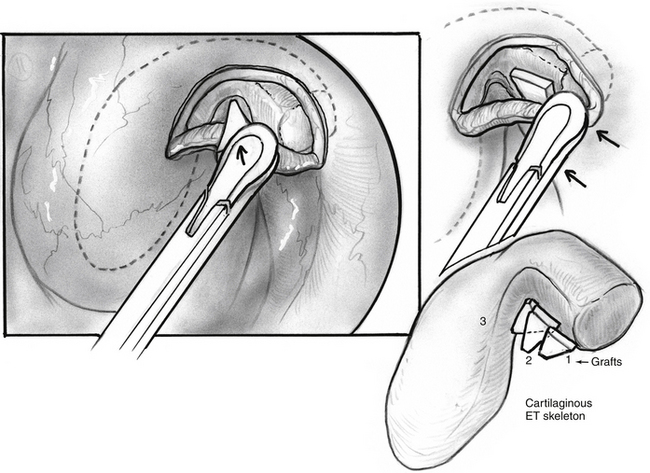

The ipsilateral nasal cavity is sprayed with pseudoephedrine-containing nasal drops. The mandible is retracted with a tonsillectomy mouth gag. A soft red rubber catheter is passed through the contralateral nasal passage and used to retract the soft palate. The nasopharynx is seen with a 45 degree rigid telescope introduced through the ipsilateral naris. An intravenous catheter, 14 or 16 gauge (2.1 or 1.7 mm diameter), is prepared, cutting it to 35 to 38 mm length, preserving the tapered tip; the lumen is obliterated full length with bone wax by pouring it melted into the lumen before cutting the catheter to size. The length is determined by the size of a patient’s head and by CT scan. The CT scan is inspected for any dehiscence of the internal carotid artery into the ET. The catheter is loaded into a custom-made piston within a tube introducer (see Fig. 7-13).17 The catheter is held in place by a small piece of bone wax having been initially placed into the introducer and against the mobile piston. The introducer with the catheter is passed through the oral cavity and oropharynx, and is brought to the proximity to the nasopharyngeal orifice of the ET under view with the endoscope. The catheter is pushed into the lumen of the ET with the piston-like movement of the introducer; engagement of the catheter into the isthmus is felt as heightened resistance.

The patulous defect has been identified as a loss of bulk in the valve within the anterolateral wall, superiorly. The senior author has injected various materials (e.g., fat, collagen, hydroxyapatite) into this location in patients. Introduction of 0.3 cm3 resulted in immediate alleviation of symptoms in all patients, but most results tend to be temporary with return of symptoms 2 weeks to several months later in most patients.17

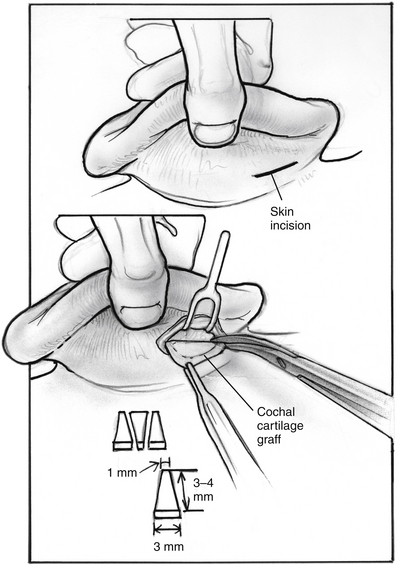

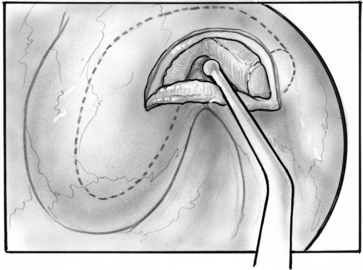

In search of a material that can be safely used to fill the valve’s defect with stable long-term results, the senior author used acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm) and cartilage grafts to augment the defect in a patulous ET reconstruction (PETR) procedure.17 AlloDerm is typically resorbed by about 65% and is no longer used because of a higher long-term failure rate than cartilage grafts. The graft is placed into a luminal, submucoperichondrial pocket made in the superior half of the ET orifice. The procedure is done using transoral and endoscopic transnasal approaches, with the patient supine and under general anesthesia. The nose is decongested by topical application of phenylephrine solution, and a mixture of lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 is injected by an angled needle into the nasopharyngeal orifice of the ET. The cartilage graft can be taken from the tragus (with the posterior perichondrium attached), concha, or nasal septum (without perichondrium). The mouth is opened with a mouth gag, and the soft palate retracted with a soft rubber catheter, introduced through the contralateral nose. The nasopharynx is viewed with a 45 degree rigid endoscope with a camera. The endoscope is attached to a gag-mounted endoscope holder. All instruments other than the endoscope are passed through the oral cavity.

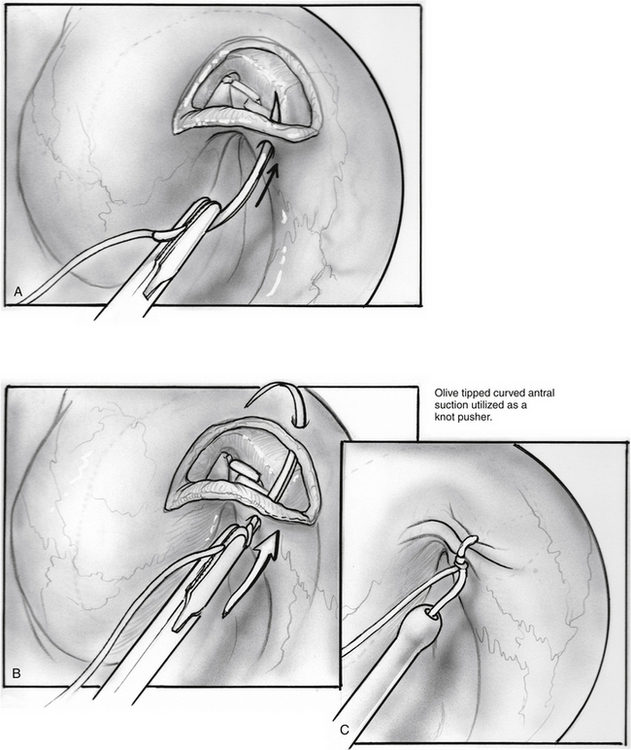

The incision is closed with two or three 4-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures on a TF needle shaped into a J toward the tip to allow for easy passage through the lateral mucosal edge after first traversing the medial edge. At least one suture is passed through one of the cartilage grafts. The suture is tied through the oral cavity, passing one limb of the suture into a curved olive-tipped maxillary antral suction while the vacuum is engaged. The suction tubing is removed, and the threaded suture limb is maintained on tension as the suction catheter is advanced to serve as a knot pusher. If the patient is to fly within 6 weeks of the procedure, a ventilation tube may be placed in the drum. Initially taking about 3.5 hours, operative time was later reduced to 1.5 to 2 hours (see Figs. 7-8 through 7-14).

The results of PETR performed in 14 ETs of 11 patients have been published.17 All patients had long-standing (1 to 38 years) patulous ET that failed previous therapies. Eight patients had a trial of myringotomy and placement of tubes, and two had undergone previous ET procedures at other centers. The most common and most disturbing symptom was autophony. All patients experienced immediate and complete relief after the operation. Follow-up duration ranged from 3 to 30 months (average 15.8 months). Symptoms were completely relieved in one patient, significantly improved to satisfaction in five patients, and significantly improved but with patient’s dissatisfaction in seven patients; in only one patient were symptoms unchanged. No complications were experienced. One patient required a supplementary hydroxyapatite injection, following which complete relief of autophony persisted for another 22 months.

Presently, we offer the minimally invasive catheter insertion procedure as the primary procedure (see Fig. 7-14). In the event of failure, we may offer insertion of a larger or a second catheter or a cartilage PETR. The catheter approach can also be used after failure of the PETR. Ultimately, obliteration of the ET and long-term tympanostomy tube can be done for repeated failures; we prefer an endoscopic method for occlusion similar to that described by Doherty and Slattery,11 but we also suture the lumen closed over the fat graft. This technique may prove to be effective for control of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after skull base operations.

1. Bluestone C.D. eustachian Tube Structure, Function, and Role in Otitis Media. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2005. pp 25-62

2. Sade J. Introduction to eustachian tube function. In: The eustachian Tube. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1985:3-28.

3. Rockley T.J., Hawke W.M. The middle ear as a baroreceptor. Acta Otolaryngol. 1992;112(Stock):816-823.

4. Proctor B. Embryology and anatomy of the eustachian tube. Arch Otolaryngol. 1967;86:51-60.

5. Misurya V.K. Functional anatomy of tensor palatini and levator palatini muscles. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:265-270.

6. Poe D. Opening and closure of the fibrocartilaginous eustachian tube. In: Ars B., editor. Fibrocartilaginous eustachian Tube—Middle Ear Cleft. The Hague: Kugler; 2003:49-56.

7. Yoshida H., Kobayashi T., Morikawa M., et al. CT imaging of the patulous eustachian tube—comparison between sitting and recumbent positions. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:135-140.

8. Kawase T., Hori Y., Kikuchi T., et al. Patulous eustachian tube associated with hemodialysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:601-605.

9. Jago J. On the function of the tympanum. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1858;9:134-140.

10. Bluestone C.D., Magit A.E. The abnormally patulous eustachian tube. In: Brackmann D.E., Shelton C., Arriaga M.A., editors. Brackmann’s Otologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001:82-87.

11. Doherty J.K., Slattery W.H. Autologous fat grafting for the refractory patulous eustachian tube. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:88-91.

12. Pulec J.L. Abnormally patent eustachian tubes: Treatment with injection of poly-tetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) paste. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1543-1554.

13. Simonton K.M. Abnormal patency of the eustachian tube—surgical treatment. Laryngoscope. 1957;67:342-359.

14. O’Connor A.F., Shea J.J. Autophony and the patulous eustachian tube. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1427-1435.

15. Virtanen H., Palva T. Surgical treatment of patulous eustachian tube. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:735-739.

16. Suehs O. The abnormally open eustachian tube. Laryngoscope. 1960;70:1418-1426.

17. Poe S.D. Diagnosis and management of the patulous eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:668-677.

18. Hazell J.W. Tinnitus II: Surgical management of conditions associated with tinnitus and somatosounds. J Otolaryngol. 1990;105:832-835.

19. Poe S.D., Pyykko I., Valtonen H., Silvola J. Analysis of eustachian tube function by video endoscopy. Am J Otol. 2000;21:602-607.

20. van der Avoort S.J.C., van Heerbeek N., Zielhuis G.A., Cremers C.W.R.J. Sonotubometry: eustachian tube ventilatory function test: State-of-the-art review. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:538-543.

21. van der Avoort S.J.C., van Heerbeek N., Zielhuis G.A., Cremers C.W.R.J. Validation of sonotubometry in healthy adults. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:853-856.

22. Di Martino E.F.N., Thaden R., Antweiler C., et al. Evaluation of eustachian tube function by sonotubometry: Results and reliability of 8 kHz signals in normal subject. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:231-236.

23. Hori Y., Kawase T., Oshima T., et al. Objective measurements of autophony in patients with patulous eustachian tube. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:1387-1391.

24. Hori Y., Kawase T., Hasegawa J., et al. Audiometry with nasally presented masking noise: Novel diagnostic methods of patulous eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol. 2006;26:596-599.

25. Kikuci T., Oshima T., Ogura M., et al. Three-dimensional computer tomography imaging of the sitting position for the diagnosis of patulous eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:199-203.

26. Zhou G., Gopen Q., Poe S.D. Clinical and diagnostic characterization of canal dehiscence syndrome: A great otologic mimicker. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:920-926.

27. Mikulec A.A., McKenna M.J., Ramsey M.J., et al. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence presenting as conductive hearing loss without vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:121-129.

28. Minor L.B., Solomon D., Zeinreich J.S., Zee D.S. Sound-and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;24:249-258.

29. Dyer R.K., McElveen J.T. The patulous eustachian tube: Management options. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:832-835.

30. Luxford W.M., Sheehy J.L. Myringotomy and ventilation tubes: A report of 1,568 ears. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1293-1297.

31. Zollner F. Die Klaffende ohrtompete, storungen dadurch und vorschlage zu ihrer behebung. Z Hals Nasen Ohr. 1937;42:287-298.

32. Ogawa S., Satoh I., Tanaka H. Patulous eustachian tube. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:276-280.

33. Brookner K.H., Pulec J.L. Auditory tube patency after injection of Teflon paste. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90:60-64.

34. Bluestone C.D., Cantekin E.I. Management of the patulous eustachian tube. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:149-152.

35. Stroud M.H., Spector G.J., Maisel R.H. The patulous eustachian tube syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;99:419-421.