Diagnosis and management of common postoperative problems

Postoperative pain

Methods of management

• Long-acting analgesic drugs given intravenously

• Local anaesthetic infiltration into the wound edges at the end of the operation with a long-acting agent, such as bupivacaine

• Regional nerve blocks (e.g. intercostal nerves for upper abdominal surgery using a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block)

• Epidural analgesia using local anaesthetic and often morphine, during and after abdominal and pelvic surgery. These do not influence the rate of anastomotic leakage

• Non-steroidal analgesics given before the patient awakes by suppository or intravenous injection. These must not be given to patients with known allergy to aspirin or other NSAIDs, a history of severe asthma or angio-oedema, bleeding disorders, renal impairment, hypovolaemia or pregnancy. Mild asthma is not a contraindication. It is also unwise to use these in operations with a high risk of haemorrhage

Analgesia for major surgery and trauma

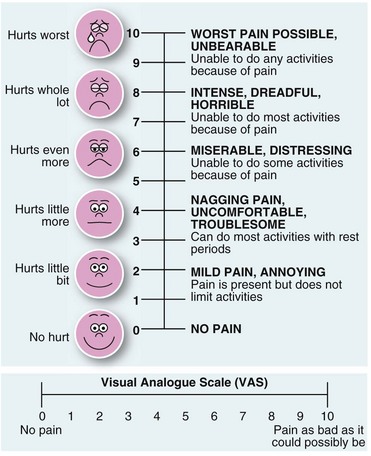

Many hospitals now provide an acute pain service, run by anaesthetists and specialist nurses. This team can plan individual analgesic strategies and help deal with pain problems as they arise. True objective rating of pain is difficult but some form of visual analogue scale chart can be helpful (Fig. 11.1).

For major surgery and trauma where epidural analgesia is inappropriate, the analgesic dose needs to be enough to eliminate the pain without causing dangerous side-effects, and to be given often enough for continuous pain relief. Effective pain control can be achieved by allowing patients to give themselves small intravenous increments of opiates using a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device (Fig. 11.2). This allows presetting of the incremental dose (often 1 mg of morphine), with a 5 minute lockout to prevent it being given too frequently, as well as control of the total dose. Continuous effective pain relief is thus easily achieved and the total dose used is often less than with intermittent injections. This technique causes minimal sedation and respiratory depression whilst maintaining excellent continuous analgesia, although it can cause opiate-induced nausea.

Excessive postoperative pain

• Local postoperative complications should be considered. Wound pain may be caused by pressure from a haematoma. In limb trauma, bleeding into or inflammatory oedema in a fascial compartment must be diagnosed before ischaemia ensues (‘compartment syndrome’). Wound pain increasing after the first 48 hours may be caused by infection. The wound is unusually tender even before redness and induration develop and there is usually a pyrexia. Other complications with lower limb pain include deep vein thrombosis and acute ischaemia. Lastly, major co-morbid conditions may be the cause of pain, for example myocardial ischaemia, or a fractured neck of femur may follow falling out of bed

• Major complications in the operation area. After an abdominal operation, excessive pain can be caused by intra-abdominal complications. These include haemorrhage, anastomotic leakage, biliary leakage, abscess formation, gaseous distension due to ileus or air swallowing, intestinal obstruction, urinary retention and bowel ischaemia, any of which is likely to require reoperation. Constipation may also cause late postoperative pain

As a rule, serious complications cause deterioration in the patient’s general condition, whereas the patient remains well with less serious complications such as urinary retention or constipation.

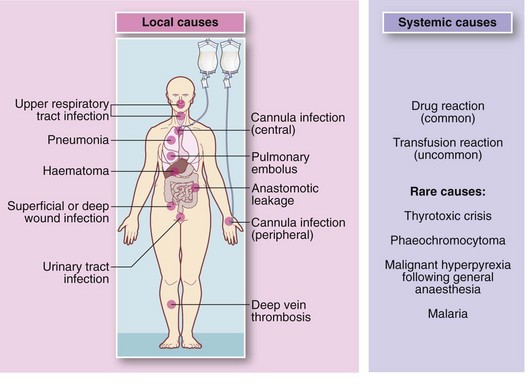

Collapse or rapid general deterioration

The doctor on call is commonly asked to deal with a patient who has ‘collapsed’ or ‘gone off’ in a non-specific way. To make matters more difficult, the patient is often under the care of another surgical team. The more serious possibilities are summarised in Box 11.2.

• Brief history of the collapse and postoperative course to date.

• Rapid clinical appraisal—check Airway, Breathing and Circulation, then changes in conscious state and neurology

• Chart review reveals changes in temperature, pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate. Check urinary output and fluid balance

• Reason for admission and preoperative state

• Pre-existing co-morbid conditions

• Nature and extent of surgical operation, including any operative problems

• Likely extent of perioperative blood and other fluid losses (including sequestration in bowel)

• Adequacy of fluid replacement

• Drug therapy—prescribed drugs? Have important drugs been given or omitted?

• Detailed physical examination

• Check blood glucose using reagent strips

• Special tests as suggested by clinical findings, e.g. ECG, chest X-ray, serum electrolyte estimation, arterial blood gas analysis, full blood count, urinalysis

Nausea and vomiting

Bowel obstruction causing nausea and vomiting

Sustained vomiting 48 hours or more after operation is usually caused by mechanical obstruction or by adynamic bowel (see Ch. 12, p. 172). Adynamic small bowel (ileus) is common after bowel operations and is difficult to differentiate from adhesional obstruction, but if it persists beyond 5 days after surgery, obstruction is more likely than ileus.

Haematemesis

Occasionally, a major upper GI haemorrhage occurs in the postoperative patient. If there has been forceful vomiting, a Mallory–Weiss tear at the oesophago-gastric junction may be the cause. Major bleeding may also arise from exacerbation of a peptic ulcer or even oesophageal varices. Seriously ill patients and the victims of burns and head injuries are susceptible to acute stress ulceration, which may cause catastrophic gastrointestinal haemorrhage (see Ch. 21, p. 298).

Other disorders of bowel function

Diarrhoea may also complicate antibiotic therapy. Several days after starting treatment, loose, frequent stools are passed for a short period, probably as a result of bacterial or fungal overgrowth. Less commonly, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea may develop, often due to overgrowth of Clostridium difficile which can be highly infective. If it progresses to pseudomembranous colitis or toxic megacolon it can become life-threatening. This is characterised by severe and persistent diarrhoea, sometimes containing blood (see Chs 3 and 12, p. 170).

Poor urine output

Pathophysiology

Acute postoperative urinary retention seems to result from a combination of the following factors:

• Pre-existing bladder outlet obstruction

• Difficulty in passing urine in the supine position

• Embarrassment at passing urine without sufficient privacy

• Accumulation of a large volume of urine during the operation and recovery, causing overfilling of the bladder

• Transient disturbance of the neurological control of voiding by general or spinal anaesthesia

• Pain from an abdominal or inguinal wound inhibiting normal contraction of the abdominal musculature and relaxation of the bladder neck

• Problems after certain operations which predispose to acute retention, e.g. abdomino-perineal resection of rectum or (bilateral) inguinal hernia repair

• Constipation—gross faecal loading is common in the elderly in hospital and is probably the most frequent cause of acute retention (and faecal incontinence)

Management of postoperative urinary retention

Catheterisation

If conservative measures fail, catheterisation is usually necessary. In females, bladder drainage and immediate removal of the catheter is done. In males, the catheter is usually left in situ until the following morning or until the patient is well. In patients with prostatic obstruction, a suprapubic catheter is a better option as it avoids urethral trauma and can easily be clamped to check if normal micturition has returned. Recurrent retention is usually caused by bladder outlet obstruction and is managed as described in Chapter 35.

Diminished urine production

If hypovolaemia is suspected, an intravenous fluid challenge of 250 ml of crystalloid solution should be given over 15 minutes or so, while monitoring JVP and urine output (Fig. 11.4). This can be repeated after 30 minutes. If this restores output, under-hydration is confirmed and fluid balance corrected to prevent acute tubular necrosis.

Fig. 11.4 Urine burette and bladder syringe

(a) Urine burette for precise measurement of urine output. Urine first enters the narrow compartment on the right to enable small quantities to be measured. It is then tipped into the main container to measure running totals. (b) Bladder syringe to flush urinary catheters suspected of blockage with debris. The nozzle is shaped to fit the end of a Foley urinary catheter. Note that full sterile precautions must be employed to reduce the risk of urinary infection

Changes in mental state

Factors which predispose to postoperative mental changes in the elderly include:

• Disorientation brought about by rapid changes of environment (from ward to operating theatre or ward to ward for example)

• Hypoxia (e.g. from pneumonia or cardiac failure)

• Infection (especially of the urinary tract)

In addition, pain, anxiety and sleep deprivation may precipitate confusion.